An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

November 26th, 2015

Five (OK, Six) ID/HIV Things to be Grateful for this Holiday Season, 2015 Edition

Some quick ID/HIV gratitude items for 2015, done rapidly as we’re hosting a big meal later today.

I wonder what that might be.

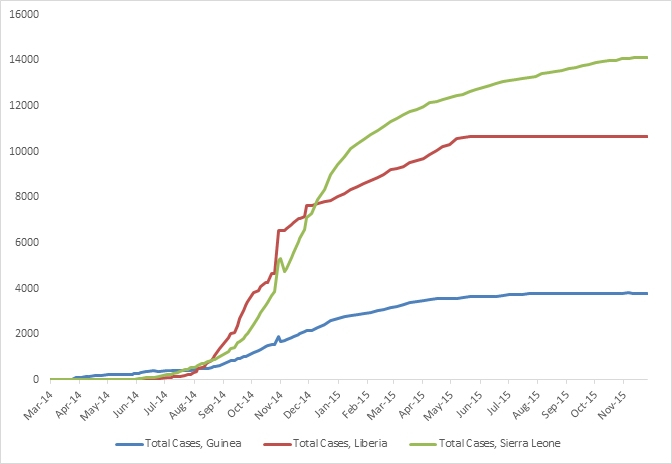

- New Ebola virus disease cases and deaths have dramatically declined. I write that sentence with some trepidation, as cases continue to occur sporadically, and this late relapse in a nurse was a chilling reminder of how little we know about this disease. Additionally, since what caused the massive outbreak in Western Africa is still poorly understood, complacency about Ebola would be very ill-advised. Nonetheless, the reason we should be grateful is shown clearly in this figure of Ebola incidence:

Last year at this time we were right in the middle of that steep upward slope, with no idea when or how cases would decline. That these curves have plateaued is due to massive local control efforts (thank you!); work on both a vaccine and antiviral therapy also continue briskly. - Antibiotic prescribing declines. Whether it’s the growing awareness of the importance of the microbiome, concerns about resistance, publicity about the dreaded C diff, fear of drug toxicity, or (most likely) some combination of the above, people are receiving fewer prescriptions for antibiotics. The data from this study confirm something that most clinicians increasingly see in their patients — some sort of tipping point has been reached, where now a growing number of people are willing to tough out community-acquired respiratory infections and nagging coughs and ear aches rather than berate their doctors with references to “green phlegm” (code for “Give me a Z-pak”). Now if we can just get the farm animals to have a voice in this too — 80% of antibiotic use in this country is for agricultural purposes.

- PrEP works really, really well when given to people who want (and need) it. Confession: I thought pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV was forever going to remain a very small piece of the HIV prevention effort. But I’ve been wrong (many times) before — hey, I thought putting cameras in phones was a ridiculous idea — and it turns out I was wrong about PrEP, too. In both the PROUD and IPERGAY (soon to be published in a major medical journal) studies, men who have sex with men who were at high risk of contracting HIV reduced that risk by nearly 90% by taking TDF/FTC. Not surprisingly, uptake of PrEP has increased dramatically in the past year, a trend I expect will continue given CDC’s efforts to get the word out.

- HCV treatment now works just as well in clinical practice as it does in clinical trials. Remember when combination HIV therapy came out in the mid-1990s, and several papers (notably this one) cited far worse outcomes in “real life” than in the clinical trials? Or when the same exact thing happened with telaprevir and boceprevir-containing regimens for HCV? Guess what — current HCV treatment is so good that “real life” (whatever that means) outcomes are outstanding, with cure rates greatly in excess of 90% for most genotype 1 patients. Although every HCV treater has a few examples of treatment failure, they are just that — a few.

- Treatment as prevention is staggeringly effective in preventing HIV — still. Did anyone expect zero HIV transmissions from HPTN 052 participants with virologic suppression? Or from those individuals in the cohort studies of “condomless sex”? I bet somewhere the Swiss are muttering under their breath (in French? German? Italian?), I told you so. Bottom line is that there really is all but zero risk.

- The end of the “When to Start” debate. The much-anticipated START study showed that even the healthiest HIV-infected people — those with CD4 cell counts > 500 and no symptoms — benefit from immediate antiretroviral therapy, with fewer HIV and non-HIV related serious medical problems. When you add these results to the transmission benefits in item #5 above, the clear answer to the question, “When to start?” HIV treatment is pretty straightforward. Now!

As for the video below, I’ve been waiting eagerly since my 8th grade typing class to see it in action — am very grateful finally to see it.

For the record, the dog doesn’t look so lazy to me, just patient.

Happy Thanksgiving!

November 22nd, 2015

Just Wondering: Quick ID Questions to Consider

Several quick ID queries, some of them answerable on the Google machine — but I’m not going there. Too busy laundering my white coat!

Several quick ID queries, some of them answerable on the Google machine — but I’m not going there. Too busy laundering my white coat!

- What ever happened to amphotericin A?

- What’s the difference between a “serovar” and a “serotype”?

- Do dogs feel bad that Pasteurella multocida is more famous than Capnocytophaga canimorsus?

- Colistin resistance is bad — but how often does colistin actually work anyway?

- No one asks you to share a room with a stranger in a hotel — why do we ask sick people in hospitals to do this? Even sick people with infections?

- Why is there group A, B, C, D, F, and G, but no group E beta strep? At least I don’t think there is. Is it like Windows 9?

- Why do all the abbreviations for “integrase inhibitor” — InI, INSTI, II — sound and look so silly? Just say “integrase.”

- Why do we say trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole with the trimethoprim part first, but the pharmacy usually writes it for our patients the opposite way?

- Don’t you think that if probiotics really prevented or helped some condition, we’d know it by now?

- Even though the name has changed, is anyone ever going to stop saying Strep bovis?

- Why are the guidelines for meningococcal immunization so complicated? Have to look them up every time.

- Why do C diff precautions start the moment we send the diagnostic test, but MRSA precautions await the results of staph susceptibility testing?

- Why was optochin never developed into an antibiotic? Is it because it doesn’t end in “-mycin” or “-cillin” or “-floxin”?

- Does anyone really know the best dosing option for strep throat?

- What proportion of doctors immediately think Aeromonas hydrophila when they hear about medicinal leeches? And what proportion who read this blog?

- Who decided it should be MRSA — and not ORSA or NRSA?

- What percentage of hospital-based ID consults recommend additional blood cultures — even when there are numerous negatives already done on that patient?

- Why did the new endocarditis guidelines advise against using penicillin for penicillin-sensitive Staph aureus? (In Boston, we call it PSSA — say it, you’ll get the joke.) In vitro, it’s the most active drug, after all.

- MALDI-TOF or MALDI-TOF MS? Seems the former should be sufficient.

- Endocarditis cases in Britain rise since they stopped using antibiotic prophylaxis for dental work — evidence that this is in fact an important preventive strategy? Or just that the British have, ahem, dental issues?

- Why do doctors always use the term “germ” in non-medical communications, but never do otherwise? And why does it mean a virus or bacteria or fungus, but never a parasite?

- When the inactivated zoster vaccine is approved, what happens to all those zoster vaccine curbside consults?

- Dogma is that you don’t need antibiotics after I and D of uncomplicated skin abscess. So why is 10 days of TMP-SMX better than 3?

- Why are certain toxic and little-used HIV drugs (ddI, d4T in particular) still on the market? Is there anyone who wouldn’t benefit from switching to something different?

- When we will stop using antibiotics to treat C diff?

- Could this white coat poll be any closer? Memories of Bush vs Gore.

Answers, opinions, speculations welcome!

Seems probiotics helped this guy (listen/watch through 1:50).

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3xJWxPE8G2c]

November 18th, 2015

Are There Remaining Challenges in HCV Therapy?

Prompted by (yet more) spectacular HCV study results, I posted the following questions on Twitter:

Is velpatasvir/sofosbuvir the endgame for HCV? And what will HCV researchers do now? https://t.co/vL2A9FOttR @NEJM

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) November 18, 2015

To which I got this reply from one of our very energetic second-year ID fellows:

@PaulSaxMD @NEJM what about coinfected patients, drug interactions?

— Philip Lederer (@philiplederer) November 18, 2015

OK, OK, I know what you’re wondering — don’t you two have anything better to do than fool around with a financially struggling social media platform?

Sure we do — but after years and years of “not getting” Twitter, I now (thanks to Phil) see some of the benefits, namely the rapid exchange of information and ideas, in a particularly efficient form.

But back to the topic at hand, which is the HCV regimen used in these latest studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine. All include the pan-genotypic NS5A inhibitor velpatasvir with the already-approved nucleotide sofosbuvir, given as a single pill once daily.

Results? Outstanding:

- Genotypes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6: 99% cure.

- Genotypes 2 and 3: 99% and 95% cure, respectively.

- Decompensated cirrhosis: 86-94%.

The results really make you wonder what more we can do to make HCV treatment better. We are definitely at the flat part of the  response curve, and fortunately it has plateaued way up there, with 95% or higher cure rates for all but the sickest HCV patients, along with exceedingly rare adverse effects.

response curve, and fortunately it has plateaued way up there, with 95% or higher cure rates for all but the sickest HCV patients, along with exceedingly rare adverse effects.

So are there remaining issues? Yes, sort of — but none of them is as pressing as the obligatory elephants in the room, which are cost and access. Let’s start with Phil’s proposed challenges, plus a few others:

- Co-infected patients. Not really a problem at all — people with HIV respond just as well as those without coinfection. (Several examples of studies cited in this post.) In fact, in many ways they’ve been easier to treat, as the patients are already used to taking medications every day.

- Drug-drug interactions. Compared to what we’ve dealt with using ritonavir and cobicistat and rifampin, these are a piece of cake — unless you’re actually using ritonavir with the “PrOD” regimen. (That’s what I’ve been calling it. I never liked “3D”.)

- Cirrhosis. Especially with a history of treatment failure to interferon-based therapies. In most studies, the newer drugs don’t work quite as well in these patients — but we’re generally talking small differences. Response rates are still pretty great.

- Patients who have failed treatment with an NS5A inhibitor-containing regimen. Indeed, this does limit our options quite a bit, and assessing for resistance is anything but straightforward, especially with non genotype 1. But we’re not completely without options — alternative sofosbuvir-based regimens will work in some patients, as the resistance barrier to this particular drug is sky high. I suspect we’ll get some clarity on this issue over the next several months.

- Patients who can’t take 12 weeks of therapy. Most studies of treatment for less than 12 weeks have been disappointing. Does a shorter course mean better adherence? Lower cost? Better outcomes? Maybe. Hard to beat the current rate of cure, but still — a regimen that could be given for 2-4 weeks would be welcome for some patients. Think H pylori treatment, if you can stand the analogy, since ID doctors know squat about H pylori therapy.

- Cost. See elephants in the room, cited above. Maybe the soon-to-be-approved grazoprevir/elbasvir. We’ll see.

So what about the second part of that tweet?

And what will HCV researchers do now?

I don’t know — become experts in implementation research? Study how to cure hepatitis B? Switch to steatohepatitis? Fibrosis reversal? Learn how to juggle clubs?

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ax0wl8pYk4g&w=560&h=315]

November 15th, 2015

Speechless

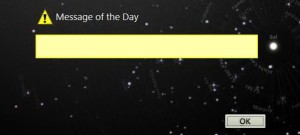

Friday, November 13, 2015, late afternoon. This time of year, in Boston, it feels like early evening, but the clock says it’s only a bit after 4pm. I log onto our electronic health record to check for lab results and patient messages, and get this:

There it is, the “Message of the Day”, complete with the this-is-important exclamation point, but the message box is empty, saying nothing. Must be some sort of programming glitch, a slip-up buried in the millions lines of code and ones and zeros that are supposed to represent our patients.

I’ve never seen this particular error before. What does it mean — what is the EHR trying to tell us, but can’t find the words? Should I report it? If so, the question is to whom — but does it even matter? The easier path is to just click the OK box and move on.

Shortly after dealing with this minor inconvenience, I hear about the events in Paris — over a hundred dead from carefully coordinated terrorist attacks, grim images coming forward of bloodied bodies and a city now frozen in fear.

Sadly, there is no OK box to click for this tragedy.

Words alone are insufficient to describe our support for the people of France.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l6vGq_rHAmE&w=560&h=315]

November 8th, 2015

New HIV Treatment “ECF-TAF” is Really All About the “TAF” Part

HIV providers and patients recently got this news from the FDA:

HIV providers and patients recently got this news from the FDA:

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved Genvoya (a fixed-dose combination tablet containing elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide) as a complete regimen for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults and pediatric patients 12 years of age and older.

(Disclosure: I have been involved with the clinical trials; you can read my full disclosures here. That involvement notwithstanding, some sort of comment seems appropriate — this is an HIV/ID blog, after all.)

The availability of elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide — hereafter abbreviated “ECF-TAF” — brings us the fifth one-pill-a-day treatment for HIV. Of course we already have something very similar, which is ECF-TDF, and hence the only thing new here is the TAF component.

So what does ECF-TAF bring us that we didn’t already have with ECF-TDF?

Based on multiple clinical studies, here are what I think are the proven differences between the two:

- Less effect on bone density. As initial therapy, TAF induces less bone loss than TDF — the former is comparable to NRTI-sparing strategies. Furthermore, in multiple clinical studies, switching from TDF to TAF improves bone density.

- Decreased renal toxicity. In several trials involving over 3000 patients, no case of tenofovir-related renal toxicity has occurred in an ECF-TAF-treated patient. TAF’s effect on urinary proteins (a surrogate marker for renal effects) is also significantly less than TDF. One unknown is whether it can be safely given to a patient with a history of tenofovir-related renal toxicity; that question is under study. The regimen is approved for use in patients with estimated GFR down to 30 ml/min.

- A lower milligram dose. As part of ECF-TAF, the dose of TAF is only 10 mg, vs 300 mg for TDF. (When not given with cobicistat or ritonavir, the dose will be 25 mg.) A lower milligram dose means smaller pills and easier coformulations.

- A novel way to simplify complex regimens. As noted here, ECF-TAF can be combined with 800 mg of darunavir to make a two-pill treatment for some patients with multi-drug resistant virus. You couldn’t do this with ECF-TDF, at least not with confidence — it hadn’t been studied, and the three-way drug-drug interaction between cobicistat, darunavir, and elvitegravir gave me pause.

- Less lipid-lowering effect. Tenofovir lowers lipid levels (mechanism still unclear), and since TAF delivers 90% lower blood levels of tenofovir than TDF, there is less of this effect. This lower tenofovir exposure is mostly a good thing (see renal and bone above), but not here. I suspect this won’t be clinically relevant, but of course we don’t have enough follow-up data since the incidence of cardiovascular events in short-term clinical trials is so low.

And here’s what’s not different:

- Antiviral activity. Though in phase I studies TAF induced greater declines in HIV RNA than TDF, virologic outcomes (meaning failures and incident resistance) in studies comparing ECF-TAF with ECF-TDF have been similar.

- Drug-drug interactions. The “C” in both ECF-TAF and ECF-TDF stands for cobicistat, the ritonavir-like PK “booster” that is necessary for elivitegravir’s once-daily dosing. A cytochrome p450 inhibitor, cobicistat has numerous drug-drug interactions — watch those medication lists carefully! Note that a combination of TAF/FTC and 9883 — an unboosted integrase inhibitor, no cobicistat required — is in development.

- Subjective side effects. There’s no significant difference in the incidence of patient-reported side effects. In other words, if your patient didn’t tolerate ECF-TDF, there is little point in trying ECF-TAF. Good news is that both are very well tolerated, with extremely low discontinuation rates for adverse events.

- The price. Encouragingly, ECF-TAF is priced the same as ECF-TDF, a decision lauded by this group. However, integrase-inhibitor based regimens remain relatively expensive (average wholesale price around $30,000/year) compared to NNRTI-based therapies, though cheaper than those that include a boosted PI.

Overall, ECF-TAF is welcome new option for treatment, and to emphasize again it’s the TAF part that makes the (only) difference. Future TAF formulations will include TAF-FTC-rilpivirine and TAF-FTC (which will need at least one other active drug) — these are expected some time next year. TAF-FTC-9883 is further away.

Meanwhile, we can continue to ponder the mysteries of choosing a brand name for a drug — “Genvoya” sounds to me like a high-end coffee maker.

November 1st, 2015

Should Doctors Still Be Allowed to Wear White Coats? You Decide

If you’re not immersed in the ID or the Infection Control world, you might not be aware that there’s currently quite the controversy about whether doctors should wear white coats.

If you’re not immersed in the ID or the Infection Control world, you might not be aware that there’s currently quite the controversy about whether doctors should wear white coats.

I almost wrote “raging controversy” — but the adjective “raging” doesn’t really fit the sort of people who specialize in Infection Control, who are some of the most measured, data-driven, and methodical individuals in all of medicine. You know the stereotype of the brash, volatile, and cowboy surgeon, the person that everyone tiptoes around?

These Infection Control folks are the polar opposite.

Still, a white coat controversy does exist, and it goes like this:

- You can culture all kinds of scary bacteria from the sleeves of white coats.

- Doctors don’t launder their white coats very often.

- These bacteria could be transmitted to patients.

- Therefore, doctors shouldn’t wear white coats.

Not surprisingly, some have advocated a “bare-below-the-elbows” approach to doctors’ attire, and famously the British National Health Service has made it policy, banishing ties as well (and predictably not pleasing everyone). There was a tremendously entertaining debate on the topic this year year at IDWeek — such a pitched battle it almost met the “raging” criteria, but not quite (you could tell the combatants really liked each other). Right here in Boston, one of our current ID fellows feels quite passionately about the issue, and writes frequently on the topic.

The missing piece in the controversy, of course, is a definitive study showing that patient infection rates are actually reduced when a bare-below-the-elbows (often abbreviated “BBE”) strategy is adopted. Short of that, we’re all essentially hostage to whomever sets these policies wherever we work. And our hospital’s policies basically follow those of Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), which “balance professional appearance, comfort, and practicality with the potential role of apparel in the cross-transmission of pathogens.”

In other words, wear white coats if you want, but keep them clean.

This data void, however, gives me permission to ruminate over some of the important and not-so-important questions that inevitably come up when contemplating white coats, and our ambivalent feelings about them.

Specifically:

- Why do some doctors wear them now, and some don’t? My wife the pediatrician said if she or one of her practice partners showed up in a white coat, the office staff would view it as bizarre as if they showed up dressed as a Roman centurion. She didn’t actually say that, but you get the idea — pediatricians don’t avoid white coats because of infection risk, but because they are considered potentially scary to kids. Meanwhile, the brilliant and fearsome Chief of Medicine during my residency considered us housestaff essentially naked unless we were wearing white coats, and the Chief Medical Residents kept a few extra in their offices on days he took Residents’ Report in case we showed up white coat-less — kind of like the maitre d’ at the formal restaurant keeping a few extra blazers in the coat closet in case someone arrives without a jacket.

- What do the patients want? Demonstrating that she was a far more compensated medical student than I, one of my classmates during medical school actually published a study evaluating patients’ preferences on doctor attire. Yes, patients liked white coats back then, jeans not so much. It’s one of many such studies appearing in the medical literature over the years; a systematic review of them is summarized in this paper published in the British Medical Journal. Consensus? Patients still seem to like them, but of course for every opinion about the reassuring message of professionalism conveyed by the white coat, there’s an opposite view that they reinforce outdated hierarchical structures in healthcare.

- What should doctors wear if they don’t wear a white coat? The obvious first thought is scrubs, but there are a few problems here. First, scrubs are basically utilitarian pajamas, and can get pretty nasty unless washed daily. Second, they don’t offer much in the way of insulation, a huge issue in the winter and in ubiquitous over-air conditioned interiors. Third, scrubs can be very unkind to certain body types, male and female alike. (You know what I mean.) Fourth, they have basically no storage space — cell phone, wallet, that’s it — forget the reflex hammer, ophthalmoscope (though it’s useless to me), or pocket manual, and wearing scrubs makes your stethoscope a permanent half-necklace. Finally, the public has lots of negative feelings about scrubs — especially when they see doctors wearing them outside the hospital, which means to adopt scrubs as standard gear means changing when you get to work, ugh. And if not scrubs? Men probably clean their suits less often than they wash their white coats, and my daughter told me recently that button-up short sleeved shirts on men are a huge fashion faux-pas, to be avoided as much as backpacks with wheels and belt clips for cell phones. Who knew?

- If white coats go, what happens to the “White Coat Ceremony” during medical school? Apparently, 97% of medical schools now have a White Coat Ceremony, the purpose of which is “to welcome new students into the medical profession and to set clear expectations regarding their primary role as physicians by professing an oath.” Does that oath now include a specified frequency of laundering, including minimum water temperature and the need to use bleach? By the way, you youngsters might be surprised to hear that these solemn and moving rituals are relatively new. Back when I was in medical school, they just left you in a room alone with a cadaver, turned out the lights, and timed how long you could stay there before you screamed for help.

- How would New Yorker cartoons designate doctors if white coats were abandoned? This is a very important question. Take a look — the overwhelming majority have the MD in a white coat, and those few that don’t typically involve surgeons in the OR. Here’s one of the rare exceptions to the above rule and 1) the guy is wearing long sleeves (not BBE!), and 2) it’s not that funny. I’d give it a 7 out of 10 on the funniness scale — now this one is funny. Note that this brilliant cartoonist often adds the head mirror to the white coat, just so you couldn’t possibly think that the white-coated person in his cartoon might be an insurance salesperson or an airline pilot.

Ok, so controversy not resolved. Please vote!

October 29th, 2015

The Most Important HIV Study at IDWeek 2015

After reporting my choice for the most important HIV study at ICAAC, I received this email from a colleague:

If that’s the most important study, I really didn’t miss much …

Now she has notoriously high standards — hard to impress her — but her opinion notwithstanding, I still think the STRIIVING study has some important messages we can apply to clinical practice today. So I stick by my choice.

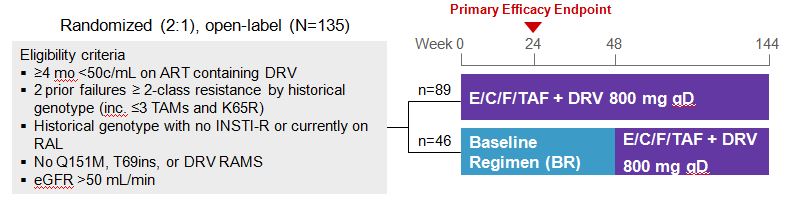

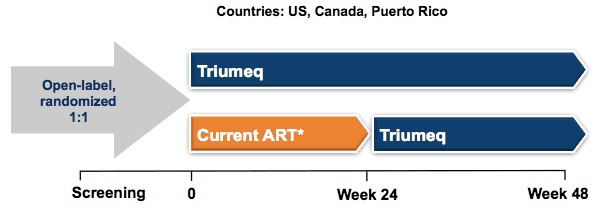

Now let me see if I can meet her approval with an IDWeek 2015 (which took place earlier this month) selection. It’s another HIV switch study, although this time with a twist. Instead of the usual switch-study population (first regimens, or only those with no history of virologic failure or resistance), it looked at a very different group — patients who were virologically suppressed but highly treatment-experienced, all with 2-class (or more) resistance, and taking multiple pills a day with a darunavir-based regimen.

Subjects were then randomized to continue their current therapy or switch to the two-pill treatment of elvitegravir-cobicistat-FTC-TAF (ECF-TAF) plus darunavir 800 mg, both once daily. (Thanks to Greg Huhn, the presenting author, for sharing the slides.)

At baseline, the regimens included a median of 5 pills, and around 60% were taking at least 6 or more pills a day. Most had a history of M184V, and a significant minority had K65R and/or PI resistance.

At week 24, 97% vs 91% of the ECF-TAF + DRV vs continued baseline regimen groups had HIV RNA < 50 cop/mL; at week 48, it was 94% and 76%, a significant advantage of ECF-TAF + DRV.

No new resistance was observed in those with virologic failure on the 2-pill arm; one subject developed resistance in the baseline regimen group, but not integrase resistance. A PK substudy demonstrated acceptable levels of both EVG and DRV, greatly exceeding IC95 and IC50 respectively.

Some comments on this study:

- Approval of ECF-TAF is expected soon, and I suspect this particular indication for switch will not be part of the product label. The data are very recent, and the study is relatively small.

- Even if it’s not in the label, however, these study results certainly suggest that some patients on complex regimens (many of whom are yearning to take something simpler) will be able to shift to just two pills a day — a welcome change.

- The PK substudy was extremely reassuring, greatly diminishing concerns about the head-spinning three-way interaction between elvitegravir, cobicistat, and darunavir. That interaction, by the way, is the reason why we shouldn’t use darunavir with the currently available ECF-TDF.

- Take a close look at those eligibility criteria — in particular the resistance ones — because they’re important. It’s why I italicized the words “some patients” in my comment above.

- Why is this so important? Patients with more than 3 TAMs, the multi-NRTI resistance mutations Q151M or T69S, or darunavir mutations were excluded. We don’t know if switching patients with any of these criteria to ECF-TAF and darunavir will maintain virologic suppression.

- Virologic rebound for patients with multi-class resistance who are stably suppressed could be disastrous — it would be terrible to take a patient with 3-class resistance and virologic suppression to 4-class resistance (including integrase) and rebound, especially since the HIV drug pipeline has relatively few investigational agents.

The take home message from this study is that when ECF-TAF is approved, a subset of our patients who are taking complex regimens could safely switch to two pills a day — ECF-TAF + darunavir.

Finding the right patients will take meticulous scrutiny of their historical genotypes. But of course that’s why they pay us the big bucks!

Next year’s meeting? October 26-30, New Orleans.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXHdqTVC3cA&w=420&h=315]

October 24th, 2015

Pumpkin-Flavored ID Link-o-Rama

As the leaves change colors and fall from the trees, the days grow shorter and colder, and pumpkin-colored and flavored merchandise shows up everywhere, I ask you this important question:

As the leaves change colors and fall from the trees, the days grow shorter and colder, and pumpkin-colored and flavored merchandise shows up everywhere, I ask you this important question:

What precisely are the infectious risks of bobbing for apples?

Off we go.

- Receiving antibiotics in childhood is associated with weight gain. The important finding in this study is that the effect occurs throughout childhood, not just infancy. Could it be that the antibiotic-obesity association will have a greater effect in reducing outpatient use of antibiotics than the risk of resistance? Lots of press coverage.

- At the other end of the age spectrum, here’s a thoughtful perspective on the widespread use of antibiotics at the end of life. I’ve covered this topic before — why are antibiotics so often given at the end of life when all other medical interventions are stopped? Paper cites one study suggesting “greater comfort, albeit shorter survival, among patients with advanced dementia and suspected pneumonia who were not treated with antimicrobials.” Sounds like withholding antibiotics could be the right move in palliative care.

- HCV therapy with paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir may precipitate hepatic decompensation and liver failure. Not surprisingly, “most” of the cases (which have precipitated an FDA-mandated label change) have occurred in patients with advanced cirrhosis.

- There are infectious risks associated with receiving injections of live cells, including Q fever from sheep cells and M abscessus from human fetal cells. Certainly infection is one good reason not to undergo these treatments; the second and even better one is that none of these therapies has any proven medical benefit. A bit more on this longstanding form of quadkery here.

- The ocular syphilis cluster on the West Coast is a reminder that in the post-PrEP, post treatment-as-prevention world, condomless sex is inevitably increasing among MSM, along with rates of sexually transmitted infections. Note that this report repeats the recommendation that all patients with ocular syphilis should 1) undergo a CSF exam (which may be negative in ocular syphilis) and 2) be treated for neurosyphilis regardless of CSF results. Which prompts me to ask — then why do the CSF exam if treatment isn’t changed based on the results?

- Transmitted NNRTI resistance does not appear to influence response to integrase-based ART. This nice analysis presented at IDWeek from a Stanford/Kaiser collaboration confirms previous reassuring findings from prospective clinical trials. And it means you probably don’t need to use a boosted PI in this situation.

- Promising results from a small (n=20) single-arm pilot study of two-drug, dolutegravir + lamivudine ART in treatment-naive patients. Think GARDEL strategy, only with DTG and not LPV/r. 20/20 are virologically suppressed at week 24, and all but one were < 50 by week 8. Note that the inclusion criteria limited enrollment to patients with HIV RNA < 100,000 and CD4 > 200. A larger (but still not comparative) clinical trial of this strategy is opening soon.

- In the vaccine world, is there anything more complicated than the recommendations for meningococcal immunization? Based on a meeting that took place this June, they’ve now changed again to include the serogroup B vaccine for late adolescents. When in doubt on vaccine-related issues, head over to the invaluable immunize.org site, in particular the “Ask the Experts” section.

- No clinically significant drug-drug interactions between ECF-TAF or RF-TAF and sofosbuvir/ledipasvir. Even with the ledipasvir slightly boosting tenofovir exposure, levels remain 5X lower than when TDF is used. ECF-TAF (“Stribild 2.0”) approval expected next month, RF-TAF (“Complera 2.0”) next year.

- Here’s a nifty case report: A 91-year-old man had 10 separate hospital visits for fevers, chills, and hypotension over a two year period, several times with positive blood cultures for Aeromonas hydrophila. The source? Contaminated well water. My favorite quote from the paper: “Culture results revealed significant overgrowth of A hydrophila from his master bathroom sink; he used this water supply to soak his dentures nightly.” Made me think of this household product — he’s old enough to have watched that ad.

- On the topic of great cases, here’s a very nice inaugural piece on the In Practice blog by Harrison Reed, who reminds us that these rare and astounding cases — zebras — are vastly outnumbered by the more common cause of hoofbeats, horses.

Warning, adult content time. In her HBO special, Amy Schumer not surprisingly has a plenty of ID-related jokes — including this surprising one:

I was dating an Infectious Diseases doctor, cause two birds …

How convenient! And by the way, Amy — if you need a new writer, you know where to find me! Right here — and now on Twitter at @PaulSaxMD.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5HlImrCEkWo&w=560&h=315]

October 17th, 2015

Dear Flu Vaccine: Please Improve!

As the supply of you and your brethren have arrived in our clinics, on our hospital floors, and in pharmacies, I thought it would be a good time to reach out and tell you how to get better.

That’s right — here, free of charge, is a to-do list for how you can improve.

Understand, I’m one of your top “boosters” (sorry for the pun), and of course I got mine this year — as I do every year. You’re better than nothing, after all.

But as a patient of mine refused his flu shot this past week — “it gives me the flu” he (wrongly) said — I became motivated to reach out and let you know exactly what you should start working on:

- Become more effective. I’m sure you think that the less said about last year’s effectiveness the better, but really — 19% protection? That’s pretty lame, my friend! Your usual 60% protection seems kind of awesome by comparison, doesn’t it, and even that’s no great shakes. OK, ok, I realize it’s because the vaccine strains didn’t precisely match the circulating ones last year, but c’mon. You can do better than that. I know you can.

- How about some durability? Let me list the number of vaccines we recommend to our patients every year.

1) Flu.

That’s it — you’re the only one. And you don’t want to be in this exclusive club. It’s no wonder that many people act like it’s tax day when you tell them that the flu vaccine is due. Again? Didn’t we do just do this, like, yesterday? - Give us fewer options. Must you come in so many different forms? It’s too complicated, like trying to choose a breakfast cereal in a big supermarket. Don’t you know that too much choice is paralyzing? Trivalent. Quadravalent. High dose. Regular dose. Attenuated intranasal mist. Recombinant egg-free. Free range and gluten- free. (I made that up.) Please, enough already. Even the vaccine experts at ACIP can’t (or won’t) make a firm recommendation. This is what they say: “For persons for whom more than one type of vaccine is appropriate and available, ACIP does not express a preference for use of any particular product over another.” Thanks, really helpful. Now what?

- Be more reliably available. Supply is notoriously erratic. Sometimes the hospitals get flu vaccines first; sometimes the pharmacies; sometimes the community-based practices. Sometimes there are no vaccines for babies. There are shortages some years — then it’s like a new iPhone release, generating absurd lines — and too much supply the next, you can’t give the things away. This year it’s the nose spray vaccine — where is it? Next year it will be — who knows? Figure it out already!

- Develop an easy, universal tracking system. People can get flu shots in so many different locations we have no idea whether our patients have received them. Doctors’ offices. Pharmacies. On the job. Pop-up “flu clinics” at the neighborhood mall, church-temple-mosque, community center. Toll booths and fast food drive-thrus (throughs?) will be next. While we like the widespread availability, it makes quality assurance programs all but impossible. Here’s an idea — how about a web site, igotmyflushot.org, where people can enter their name and date of birth, and electronically release the information to their doctors? Yes, I know it’s a great idea. You’re welcome.

- Make it more understandable what you prevent. Email from non-MD friend:

Friend: “Is there flu about? Wife has fever, nausea. Son too.”

Me: “Yes there’s flu. But flu is mostly a respiratory illness — cough, sore throat, that kind of thing. Sounds like they have a stomach bug.”

Friend: “Oh yeah. Both had questionable chicken tacos at State Fair yesterday.”

Ok, maybe this misunderstanding isn’t really your fault. But somehow I believe that if you were more effective, the public would have a clearer understanding of what you prevent (on a good year) and what you don’t, and more confidence that they received something that works. Here’s what you prevent: Influenza. Here’s what you don’t prevent: Colds. Stomach bugs. Various other causes of fever. Is that so hard?

Remember, I offer the above suggestions even though I’m a strong advocate of getting the flu vaccine. It does work sometimes, influenza is a miserable illness, and frankly one could justify it solely on altruism — who wants to be the disease vector that triggered a hospitalization in a baby, a frail elderly person, or someone with a weakened immune system?

Still, there’s room for improvement. Ok, lots of room. And we can dream, can’t we? Just like the guy in the video below.

Signed,

An Infectious Diseases Doctor with a Slightly Sore Left Arm (but it’s not too bad)

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gasAm4DIVsg&w=560&h=315]

October 13th, 2015

Yes, There Are Important HIV Studies at ICAAC and IDWeek — Here’s One

Both ICAAC and IDWeek (formerly IDSA) are now over, IDWeek ending this past Sunday.

Both ICAAC and IDWeek (formerly IDSA) are now over, IDWeek ending this past Sunday.

These are the two large Infectious Diseases scientific meetings that take place each year in the Fall. They’ve been battling it out for years for attendance, but it looks like finally IDWeek (formerly IDSA) has won the Fall slot — ICAAC is moving next year to the Spring, where I assume it will stay.

Regardless of which meeting one attends, or when they happen, a common complaint heard from HIV-specialist types goes like this:

Well, it’s not like CROI — hardly anything here new and important.

Well, of course it’s not like CROI — that’s a whole meeting devoted to HIV research, both clinical and basic. It’s unreasonable to expect there will be anywhere near the number of oral sessions, posters, and plenaries on HIV at non-CROI meetings because, obviously, ICAAC and IDWeek have to represent the full breadth of material in the field.

But there usually is some good stuff, studies that could significantly impact clinical practice. Here’s the most important HIV study from ICAAC, and soon the notable ones from IDWeek.

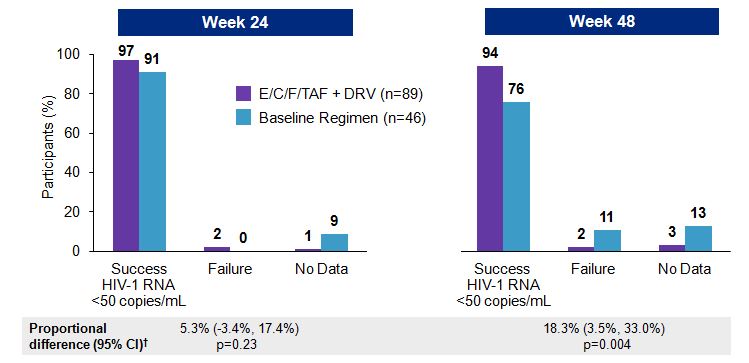

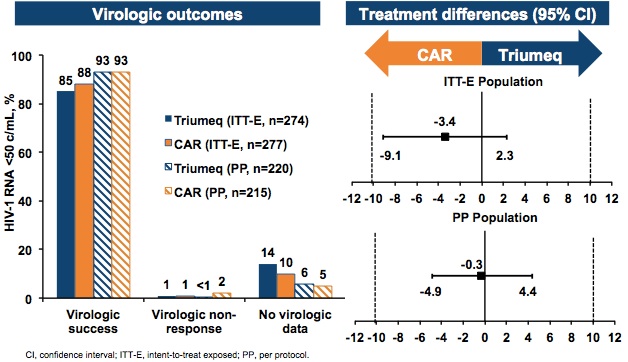

In the STRIIVING study, 551 virologically suppressed patients were randomized to stay on their regimen or to switch to ABC/3TC/DTG; it was open label (images thanks to the essential natap.org):

Eligibility criteria included being on first or second regimens with no history of treatment failure, and HLA-B*5701 negative.

At the end of 24 weeks, treatment success (HIV RNA < 50 copies by “snapshot”, meaning also still in study) was observed in 85% and 88% of subjects in the switch vs continue current ART arms respectively:

There were no virologic failures or emergent resistance in either arm. 4% (10 total — not 10% as I erroneously wrote) of the ABC/3TC/DTG group stopped the study due to adverse events (none considered serious) vs. zero in the continued ART arm. Treatment satisfaction at week 24 was significantly higher for those on ABC/3TC/DTG.

A few comments on these results, which were both reassuring and disappointing at the same time:

- There are now four available single-tablet treatments for HIV, and all have had prospective, randomized switch studies similar in many ways to this one — previously TDF/FTC/EFV, TDF/FTC/RPV, TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI for PI and NNRTI switches.

- Up until now, all of these studies numerically (if not significantly) favored the switch to the single tablet — not really surprising, as patients entering these studies typically want to simplify their regimens.

- Why didn’t this happen in STRIIVING? I can think of three kind of overlapping reasons: 1) A high proportion of subjects were already receiving integrase-based (and hence well-tolerated) treatments; 2) Also a high proportion were already on single-tablets; 3) All of these single-tablet treatments (before this one) would necessarily include TDF/FTC, and many of the multi-tablet regimens would as well. There’s probably a somewhat less-favorable tolerability profile of ABC compared with TDF, independent of hypersensitivity reactions (which didn’t happen in this study, obviously, since all were HLA-B*5701 negative).

An interesting irony is that the SINGLE study — which emphatically put DTG on the map — demonstrated superiority of ABC/3TC + DTG over TDF/FTC/EFV, results driven by better tolerability. Think about that one, and what it says about efavirenz.

Take-home message? Switching to ABC/3TC/DTG will mostly be successful (especially virologically), but a small fraction might have side effects that makes them prefer what they’ve already been on.

Anyway, that’s the most important HIV study at ICAAC. Coming soon, the most important one (or two or three, haven’t decided yet) at IDWeek.

Good time for a baseball moment. Congrats, Cub fans! (So far.)

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WOYME2Q4nAg&w=560&h=315]