An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

April 3rd, 2025

Gepotidacin — New Antibiotic or Rare Tropical Bird?

A Blujepa! (Drawing by Anne Sax.)

Imagine you’re birdwatching in the Costa Rican rainforest, Merlin app in hand. A flash of iridescent blue catches your eye. You scan the canopy and whisper excitedly:

Look, it’s the elusive Blujepa! A rare sighting!

No, not a real bird, but the brand name of gepotidacin, something rarer — and arguably more exciting — than a tropical bird, at least to us ID geeks: a brand new antibiotic class for treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. That’s right, a first-in-class triazaacenaphthylene antibiotic, approved by the FDA on March 25 for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections (uUTIs).

(If you’re wondering about pronunciation, I have on good authority it’s, JEP-oh-TIE-dah-SIN. Say it fast — it kind of sounds like an obscure progressive rock band, doesn’t it? Pretty sure Gepotidacin opened for Emerson, Lake & Palmer in 1974.)

Approval of the drug was the direct result of favorable clinical trials, EAGLE-2 and EAGLE-3. (Yes, more birds. You’d think this antibiotic came with feathers.) In both of these studies, 5 days of gepotidacin was noninferior to nitrofurantoin; in EAGLE-3, it also met criteria for superiority. The most common side effect was diarrhea, but it was overall well-tolerated.

So cue the ID fanfare.

(Muted trumpets only—we ID docs must always maintain antimicrobial stewardship mode. And let’s be honest — no one really knows what a “triazaacenaphthylene antibiotic” is, but that seems to be the convention to cite the biochemical structure of new antibiotics, as if any of us speak that language. Linezolid was frequently introduced as “the first oxazolidinone antibiotic”, whatever that means.)

To put this gepotidacin approval into context: the last time we had a new class of antibiotics for this indication, people were listening to Genesis and Yes and ELP on cassette tapes — maybe even 8-track tapes if you were stuck driving around your beat-up Chevy Nova. Since then, our therapeutic options have largely consisted of dusting off the same old standbys — TMP-SMX, nitrofurantoin, and if needed, fosfomycin or a fluoroquinolone. The last of these, of course, has tumbled out of favor, what with the tendons, the CNS effects, the QT issues, and the black box warnings piling up on your bedside table like overdue library books. And fosfomycin isn’t really that effective, is it?

Enter gepotidacin. Not only is it orally bioavailable — always a win for treating UTIs outside the hospital — but it also has activity against some resistant gram negatives that have increasingly shrugged off our old reliables. The drug inhibits bacterial DNA replication by targeting two essential bacterial enzymes: DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. This dual inhibition mechanism is unique, and different enough (we hope) from quinolones to limit cross-resistance.

Of course, the excitement is tempered by the usual caveats:

- the approval is currently for uncomplicated UTIs only

- it won’t be cheap (pricing is not available yet, but one can presuppose)

- the package insert includes a warning about avoiding the drug in people with QT prolongation — a caveat that also applies to quinolones.

Finally, approval of any new antibiotic is accompanied by the low-level anxiety that overuse will have us back where we started by the time we learn how to pronounce it properly.

Still, if gepotidacin can keep some patients with resistant E. coli out of the hospital and away from IV carbapenems, that’s a net win.

And if the distinctive call of the Blujepa brings to mind Rick Wakeman noodling through a virtuosic keyboard solo, well, that’s just a bonus. Take it away, Rick!

Ok, I’ll stop now. This is getting way too silly.

March 5th, 2025

What Is the Future of Treatments for COVID-19?

Photo by Alexey Komissarov on Unsplash

In this raging flu season, where people with influenza-related illness outnumber those with COVID-19 for the first time since the pandemic hit in 2020, we might be fooled into thinking that we no longer need better treatments for COVID-19. This would be a mistake — this virus still causes much misery, peaking each winter but circulating year-round, destabilizing lives everywhere.

But how will we get these better treatments? How can we do clinical trials with meaningful end points adapted to the current clinical spectrum of the disease? After all, what we have now has some big-time flaws.

These are the questions raised by the SCORPIO-HR study of ensitrelvir, just published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (of which I’m Editor-in-Chief), along with an insightful editorial commentary. Ensitrelvir is a SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitor similar to nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), but it’s once-daily and doesn’t need the ritonavir; it’s already approved for use in Japan and Singapore.

In the study, around 2000 non-hospitalized adults with symptomatic COVID-19 were randomized to ensitrelvir once daily for 5 days or to matching placebo. The primary end point was time to sustained reduction of 15 COVID-related symptoms, with secondary end points of time to resolution of a smaller subset of symptoms, as well as viral load reductions.

For the primary end point, the study results were negative — time to resolution of all 15 symptoms was 12.5 days for ensitrelvir, 13.1 days for placebo, a non-significant difference. The treatment did better with secondary end points of time to resolution of 6 symptoms (stuffy nose, runny nose, sore throat, cough, low energy or tiredness, and feeling hot or feverish) and SARS-CoV-2-viral load reduction, both of these statistically significant in favoring ensitrelvir. The treatment was also well tolerated, with no detected safety events of note and rare virologic rebound.

So what should we do with these results? As with Paxlovid in a lower-risk or vaccinated population, ensitrelvir failed to achieve its primary end point. Yet the treatment was active for faster recovery from certain very common symptoms; whether one values this clinically would be a personal preference. One could argue that resolution of all symptoms set the bar too high for an antiviral in our current era of near universal pre-existing immunity.

In the accompanying editorial, Drs. Beatrice Zim and Cameron Wolfe take on the challenge of how to design clinical trials for COVID-19 when the clinical severity of the disease has so dramatically changed. They advise:

The largest unmet opportunity is likely for trial teams and regulatory authorities to be creative in building adaptive design into protocols that cannot only move with the evolution of therapeutics but also with the clinical landscape … Modified regulatory opportunities that are capable of handling modified trial design should be explored in preparation for future pandemics as we reflect on our successes and trial failures of the last few years.

Meanwhile, the venue for making such changes now faces an uncertain pathway. A planned meeting of government regulators, academic clinical trialists, and industry representatives to discuss trial designs for COVID-19 was cancelled unexpectedly earlier this year. Consider this meeting yet another casualty of changes at the top, which have included cancelled meetings on vaccines and reviews of submitted research grants.

Ugh.

But I don’t want to end on this (now familiar) depressing note, and finish instead with some brighter news — ensitrelvir as post-exposure prophylaxis reduced the incidence of COVID-19 in household contacts. It’s the first antiviral to demonstrate this benefit, one not observed with either Paxlovid or molnupiravir in prevention trials. We’ll see more details of this study presented at next week’s Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in San Francisco.

February 27th, 2025

Tragic Childhood Death from Measles Reminds Us That Some Don’t Understand Either the Medical Significance or the Human Heart

My ID colleague Dr. Adam Ratner, Chief of Pediatric ID at NYU Medical Center, just published an insightful and remarkably timely book called Booster Shots: The Urgent Lessons of Measles and the Uncertain Future of Children’s Health.

Chapter Six is entitled “Making Nothing Happen,” and it starts off with this especially profound paragraph:

Prevention can be a tough business. A pediatrician talks to a parent about choking hazards or sleep positions or bike helmets, but she never gets to know which specific children that advice has helped. You can’t see prevention unless you broaden your view, looking at populations over time. Getting rid of leaded gasoline decreases childhood lead poisoning; changing recommendations about infant sleep positions lowers the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. But you don’t get to know which kids benefited — who would have not worn that helmet and had the bike accident, tipped over that unsecured television stand, died of SIDS… Vaccines are one of our best tools for prevention. They are amazing inventions that prevent serious diseases so kids can get on with their lives. But you never really know exactly who they helped. Vaccines are masters in making nothing happen.

I emphasized the last sentence, because it is the opposite of this “nothing” that happened to that poor child in Texas — who by not receiving their recommended measles vaccine, missed the opportunity for “nothing” and now is tragically dead.

And some of the responses to this case, including from the very person charged with running our Department of Health and Human Services, reveal significant weaknesses in understanding both the medical significance of the case, and, just as damningly, the human heart — how we feel when reading about a childhood death. These comments clearly aim to downplay the importance of this outbreak in general, and the death of this child in particular, so I’ll follow them with corrections:

- “It’s not unusual.” In fact, the last measles death in the United States occurred in 2015, in an adult. So it’s the opposite of “not unusual.”

- “Outbreaks happen all the time.” This is the largest outbreak in Texas in more than 30 years. Measles was eradicated in this country in 2000, with sporadic cases happening only from international exposures. The drop in measles vaccination rates in some regions since then has led to some large local outbreaks — including this one in New York City which motivated Adam to write his book.

- “Those hospitalized are mainly there for quarantine.” Not according to the chief medical officer at the hospital, Dr. Laura Johnson, who said “We don’t hospitalize patients for quarantine purposes.”

- “Everyone I know had measles growing up, including me, and we all turned out fine.” That’s because with nearly universal infection, the denominator was huge. But before the vaccine became available in 1963, 400 to 500 people died of measles each year, most of them children. There’s your numerator.

- “It’s just one death out of 124 cases, while 1 in 36 kids has autism.” The measles vaccine does not cause autism. The original paper was based on fraudulent data, and later retracted; multiple other population-based studies have found no relationship.

- “If everyone else gets the vaccine, why should I have to worry about it for my child?” This isn’t so much a lack of medical knowledge problem, but a selfishness problem. Take a look at yourself in the mirror.

Let me turn now to why pediatric deaths and illness weigh so heavily in the minds of all healthcare providers and public health officials. It’s a lesson I’ve learned first-hand by being married to a pediatrician, watching my wife consumed with worry when a single patient in her practice is seriously ill. It’s captured well in this quote from Dr. Burton Grebin:

The death of a child is the single most traumatic event in medicine. To lose a child is to lose a piece of yourself.

This is why medical students, interns, and residents have so much closer supervision in pediatric teaching hospitals than in general hospitals. Why surgeons have to train an extra-long time to become pediatric specialists. Why pediatric practices field calls 24/7 from worried parents (especially first-time parents) about every little thing. (But some aren’t so little.) And it’s why the loss of a child is considered one of the most traumatic experiences an adult can have.

This is not ageism; this is human nature — who we are. And if the raw emotions don’t resonate, here’s some simple math: Let’s say this death in Texas was a 10-year-old child; the death robbed this person of approximately 70 years of life, of being part of and building a family, of contributing to our society. And it’s not just deaths that the measles vaccine prevents. A case of encephalitis with residual neurologic deficits could lead to decades of disability, with extraordinary individual and societal costs.

So let’s remember that lifesaving childhood vaccines are indeed “masters in making nothing happen.” In this case, nothing sure beats the alternative.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not represent those of NEJM Journal Watch, NEJM Group, or the Massachusetts Medical Society.

February 21st, 2025

The Language Grouch Returns

Plaster anatomic head, 1900.

If you’re an ID doctor, there’s a lot to be grouchy about these days. This. This. THIS! The list is long — and growing. Longtime readers with an interest in ID: I ask that you please contact your members of Congress to convey the harmful impacts of the workforce cuts at the CDC, NIH, VA, and other agencies. Thank you.

Now, on to the topic of today’s post — a break from the news but maintaining the grouchy mood to discuss some words or phrases I deeply dislike. We’ll come to a new one in a minute, but first a review of a few others already in my penalty box:

- HAART. I sense this one is vanishing, especially among us ID and HIV specialists — either that or people are afraid to say it in front of me. Seems that ART, standing for “antiretroviral therapy,” has finally triumphed. Hooray! Whether my campaign against HAART has anything to do with its demise is unknown, but I’m happy to take credit. In fact, I’ll add that to my CV now.

- Thanks in advance. As a reminder, I vastly prefer (even welcome!) a simple “Thank you” or “Thanks” when a person asks for something. My wife thinks this pet peeve of mine is beyond petty, saying “You want people to thank you and be appreciative, but at the same time you don’t approve their way of doing so. That’s not fair.” Good point — but a Thanks in advance innocently placed at the bottom of an email reminding me to complete my annual HealthStream modules, or a request for 3 learning objectives for an upcoming talk, still rankles. Oh well.

- Quick question. It’s possible every ID doctor gets hives when they hear this one, since the range of complexity in these “quick questions” is vast — and truly unknowable when someone starts out by greeting you with Can I ask you a quick question? I shared this distaste for the “quick question” prelude with an experienced (and excellent) nurse, and she told me I have misinterpreted the intent of the “quick” — it’s not to meant to demean the knowledge of the queried person (me), but to soften the impact of the curbside to follow. She’s no doubt right — people are trying to be nice! — so I’ve become much more tolerant of this one. Preemptive antihistamines are no longer required to prevent the hives.

But this is just a partial list. So today I’m bringing back the Language Grouch to introduce another unfavorite phrase — and this time it’s a common request:

Can I pick your brain?

Every time I see this one, I immediately think about what it means literally. This would involve cracking open someone’s skull, rooting around inside, and then using a sharp tool to pick at what most people consider the most important organ in the body. The fact that neurosurgeons do this routinely is still unfathomable to me, all these decades of being a doctor later.

But, as the saying famously goes, I’m no neurosurgeon (or rocket scientist), which puts me with roughly 99.999% of the population. And for us non-neurosurgeons, being an active brain picker would not only be inappropriate — it would also get us arrested. Don’t do it.

But of course the request is metaphorical — people who say, Can I pick your brain? aren’t asking to perform a craniotomy. What they’re after is information, not chipping away at your white or gray matter. I know this because I distinctly remember the first time I got the request, which occurred way back in my senior year of college, and no doubt explains my distaste for it. Pull up a chair, here’s the story:

I was taking a wonderful history of music course, the kind of broad survey that completely changes your life by introducing you to something you never really understood. It was the second semester, and we were on to some of the heavy hitters — Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schubert, Chopin, Brahms. The standard classical music canon.

Our “homework,” if you could call it that, consisted of going to the music library and listening to the greatest music of Western civilization in the listening lab, along with an annotated score. Homework! I distinctly recall listening to the opening notes of Beethoven’s Fourth piano concerto as one of my assignments, heard through the special headphones they gave us when we checked out the recordings. Hearing those gentle notes, then the early key change from the orchestra right after the opening, and reading along in the score — it literally gave me chills!

For some context, the early 20-something me had mostly been listening to Led Zeppelin, Blondie, Steely Dan, Elvis Costello, and The Pretenders — Genesis and Yes were the closest I’d come to classical music. Discovering these 19th century great works of music was a revelation. To call me an enthusiastic student barely begins to describe how happy this class made me. I couldn’t get to the lectures fast enough.

The course also had weekly small sections, taught by a fun and funny graduate student memorably named “Fla.” (It must have stood for something. I wonder where he is now. Definitely not picking brains.) I was the kind of student who, if you’re not really into this music stuff, you’d find annoying. In our weekly small teaching sections, I sat at the front of the class and actively engaged with Fla, absorbing his every word.

In the same class was a (sort of) friend of mine, who I’ll call Brian to protect his identity. I’m not saying his large size and ability to push people around and knock them over while wearing pads and a helmet helped him get into college, but just sharing that “talent” of his shows that I have my suspicions.

Not only was Brian indifferent to the charms of the music course, but he also teased me about what he considered my very teacher’s pet-like behavior. Most of the teasing happened in our dorm’s dining hall because he stopped going to the small sections early in the course.

But when it came to prepare for our final exam, Brian reached out to me because there was simply no way to cram the listening assignments into the time he had remaining before the test. Listening to music takes time — you can’t speed it up, they’re not digital podcasts.

Not only that, one of the goals of the small sections was to highlight the most important material, always a harbinger of what was to be on the tests. And Brian had only attended a tenth of the classes — and I’m being generous with that estimate. Fla held no charms for him.

So here’s what Brian said (he was a last-name-first user):

Hey Sax — can I come over sometime and pick your brain about the key material for the music final?

How would you have responded?

Take it away, Ludwig. This music still gives me chills.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not represent those of NEJM Journal Watch, NEJM Group, or the Massachusetts Medical Society.

February 14th, 2025

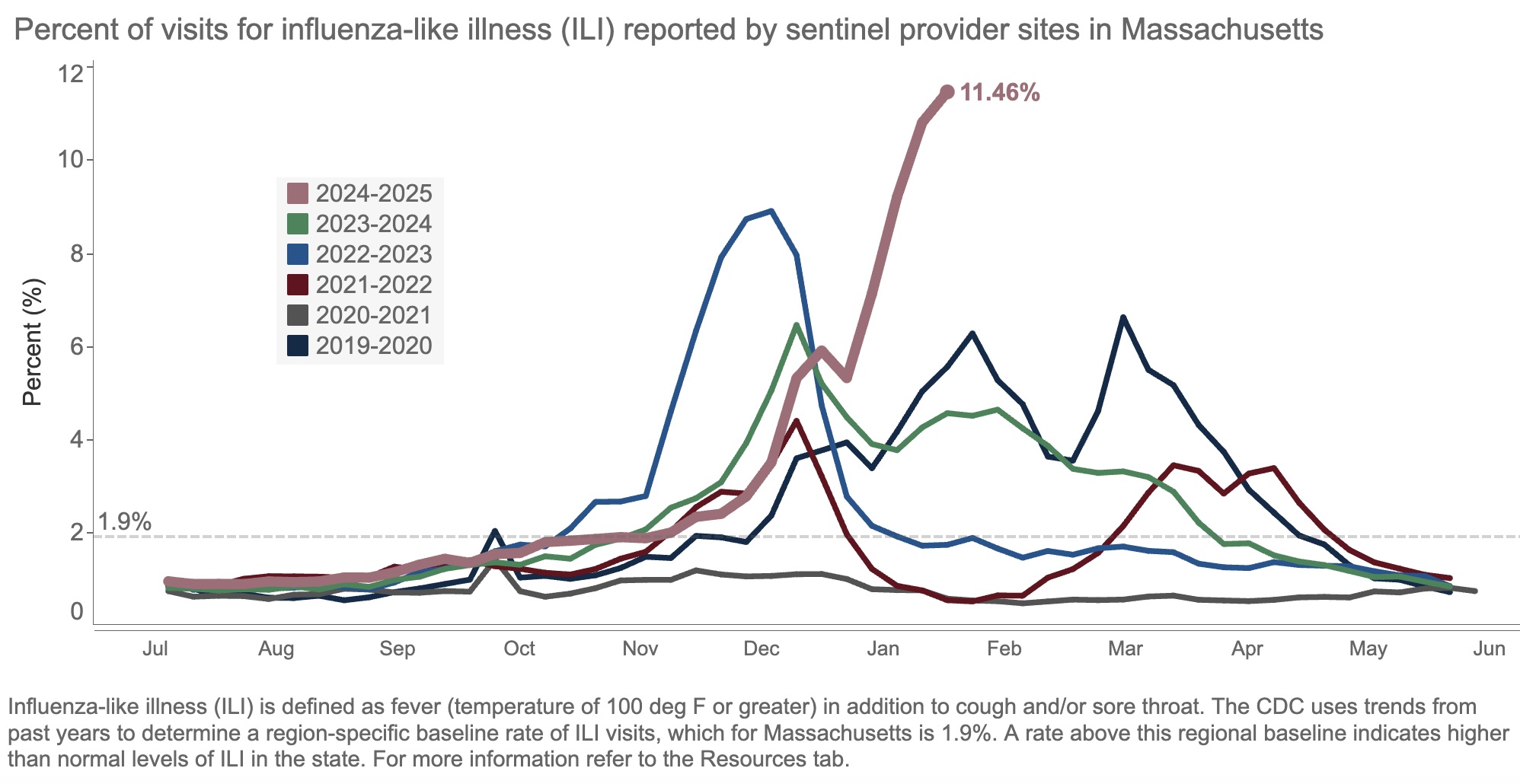

This Year Influenza Came Back to Remind Us It’s Not Messing Around

If it seems like pretty much everyone you know either has the flu or is recovering from it, it’s because we’re in the middle of the worst flu season in over a decade.

Take a look at this figure, from our state’s surveillance data, updated yesterday:

The result of all this “influenza-like illness”? Patients are deluging outpatient clinicians with messages about fevers, sore throats, coughs, and related symptoms. Hospital beds and ICUs fill up with chronically ill people whose condition has worsened due to the flu. Emergency rooms, already overstrained, park sick people in hallways awaiting evaluation and treatment.

Yes, it’s bad out there, folks. This week, we heard that our hospital has four times as many people hospitalized with the flu than as those hospitalized with COVID-19, the first time this has happened since the pandemic.

One of the most common questions we ID doctors get when the flu season is bad, or late, or just strange, is, “Why this year?” The honest answer is this humble three-word sentence:

We don’t know.

Some have blamed the cold weather this winter without much in the way of a significant thaw. Maybe, but other cold winters haven’t necessarily had this much flu. Plus there’s plenty in southern states.

Others cite the low rate of influenza vaccination, in reaction to overzealous (in some views) COVID-19 vaccine recommendations. Perhaps, but this has never been a popular vaccine.

A third theory is the fact that masking and other infection prevention activities in the community have ended. I doubt it’s this because masking was pretty much over last year and even the year before.

Some have asked me if this year’s strain of flu is somehow different, and the answer is that surveillance molecular data do not so far suggest this is the case. This is in contrast to the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, where during April (!) flu cases surged because of the emergence of a novel H1N1 variant to which younger people had little immunity.

Related, one cause of this year’s high number of cases emphatically isn’t a flood of cases of “highly pathogenic” avian influenza, H5N1. Despite active surveillance at the state level, we still are not seeing this illness from this strain to a significant degree — fortunately!

Note that I put the words “highly pathogenic” in quotes. H5N1 is of course of great concern because we have no natural immunity to it. If it emerges as a human-to-human pathogen, we’re looking at an explosion of cases, analogous to or worse than 2009. That’s bad enough.

But another major worry is that it might be intrinsically more virulent, more likely to cause severe disease per case. But the cases of H5N1 reported thus far in the United States from animal sources have had a wide spectrum of severity. At one extreme there has been a death, and at least one ICU admission; at the other end of the spectrum, many have had mild illness (conjunctivitis seems particularly common), and a recent serologic study in 150 bovine veterinary practitioners found 3 positive cases — all asymptomatic.

So I’d propose we remove the two-word phrase “highly pathogenic” as a common modifier of H5N1 until we really know whether it deserves this scary label — not just in birds and cats, but also in humans.

And please, let’s press on with the following:

- Active influenza surveillance, with transparent reporting of data. This recent government action to reduce the CDC workforce will not make this easier. To quote one of my former colleagues who works there right now, “It’s a very sad time for public health.” 100% agree.

- Re-invigorated research to improve the flu vaccine. That universal flu vaccine can’t come soon enough.

- Further drug development to improve flu treatment. Can I interest anyone in interferon lambda again, which was effective in COVID but never developed? It’s a potential treatment for respiratory viruses that may be agnostic to etiology.

Here’s hoping.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not represent those of NEJM Journal Watch, NEJM Group, or the Massachusetts Medical Society.

February 6th, 2025

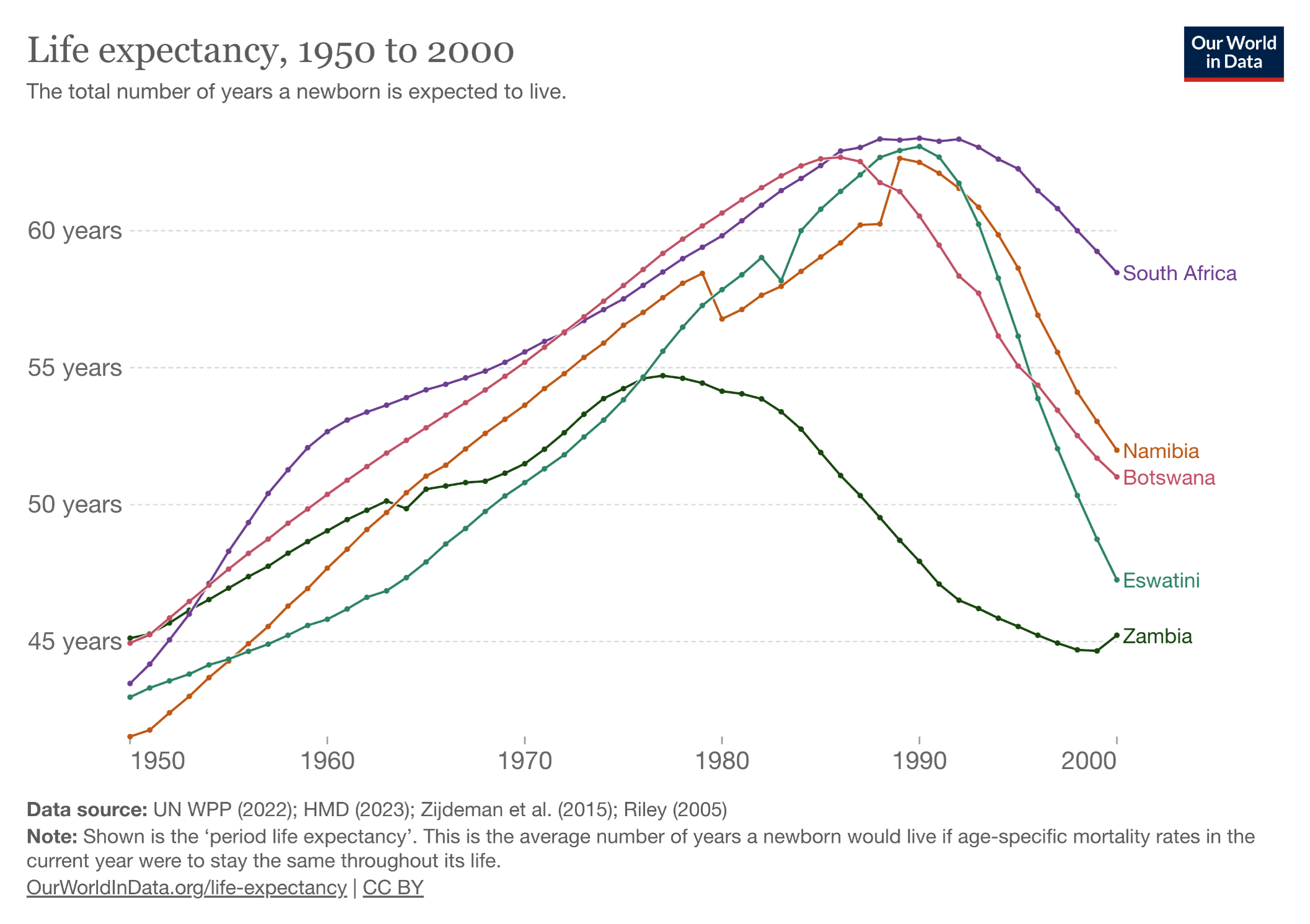

Could This Be the End of PEPFAR?

Short email from a longtime colleague, working in Africa at a PEPFAR site:

Without USAID, PEPFAR is essentially dead.

I got chills reading this.

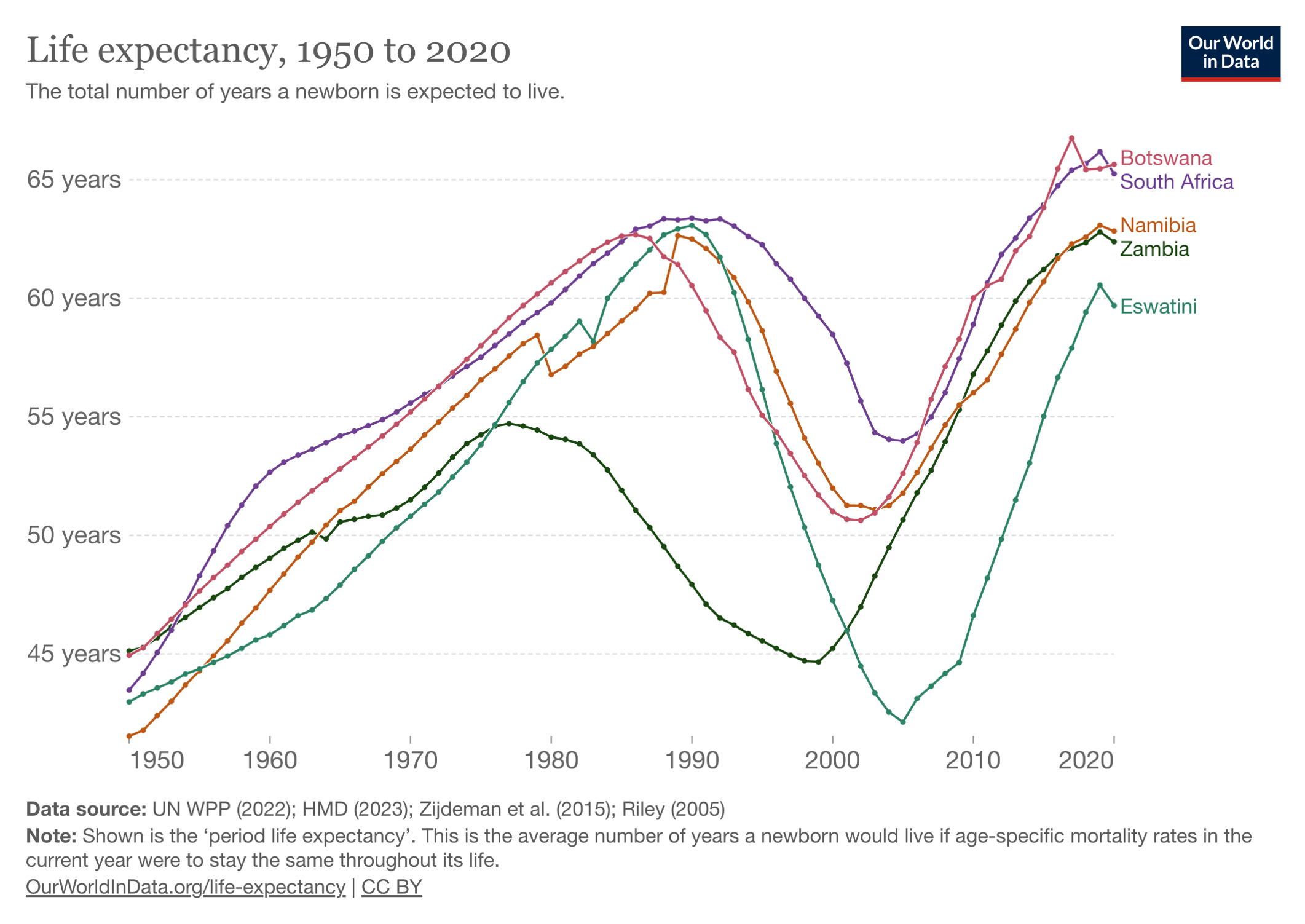

PEPFAR, the abbreviation for the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, started in 2003 under the direction of President George W. Bush. To say it’s been a resounding success undersells the impact of the program. Take a look at these two graphs, first the trend in life expectancy in several African countries (all PEPFAR recipients) before access to HIV therapy:

Now let’s look at what happened after the broad roll-out of HIV treatment, greatly facilitated by PEPFAR:

The PEPFAR program shows what happens when you pour resources into a devastating problem with a highly effective solution — in this case, a rapidly progressive and fatal disease of younger people (AIDS), with subsequent halting of that disease with antiretroviral therapy. Widely cited — and credible — estimates are that PEPFAR has saved more than 26 million lives. It has been so effective that for years it garnered bipartisan support from U.S. politicians who otherwise agreed on hardly anything.

What does USAID have to do with PEPFAR? USAID collaborates with PEPFAR and local partners to implement HIV programs, ensuring the delivery of antiretroviral therapy and other critical services. The sudden freeze in aid disrupts these efforts, potentially jeopardizing the health of countless individuals who rely on consistent HIV care. To quote again my colleague:

USAID manages the supply chain with multiple donors and products — drugs, reagents, equipment. They represent a substantial portion of the PEPFAR budget in my country.

Some have argued that provision of HIV care internationally should shift to be the responsibility of the host countries, especially now that ART has become so inexpensive and widely available. While I understand this argument, isn’t the sensible approach to make this transition gradually, or at least with some warning? And what about the other essential work of USAID? If this action is done solely to save the Federal government money, it’s not going to have much effect. As a reminder, only around 1% of the Federal budget goes to economic foreign aid, and not all of that to USAID.

Beyond the primary concern, which is the health of individuals receiving care and treatment through this program, there’s the reputation cost for our country. A country that supports effective foreign aid in poor nations is considered generous and kind; one that suddenly pulls such aid the polar opposite — selfish and cruel. Another communication from a colleague in a different country:

As a result of the PEPFAR/USAID freezes, we lost a third of our staff in our HIV clinic, mostly people who dedicated their entire professional lives to the clinic. The offices are empty and corridors echo where they didn’t before.

Let’s contrast this with the joy this program engendered when it started. I distinctly remember meeting a doctor from Nigeria in the early days of PEPFAR; he was smiling broadly at the extraordinary effectiveness of ART that he could now give to literally hundreds of his patients. Shaking my hand, he said — “We cannot thank you enough. Please tell President Bush.”

I never met the former President, but I certainly would do so if I had the chance.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not represent those of NEJM Journal Watch, NEJM Group, or the Massachusetts Medical Society.

January 25th, 2025

Let’s Hope the MMWR Resumes Publication Sooner Rather Than Later

To us specialists in Infectious Diseases, there are certain verities we hold near and dear to our hearts:

- Antibiotics are miracle drugs, but the bugs will become resistant if we don’t use them responsibly.

- Certain childhood vaccines (e.g., measles, polio, H flu type B) stand as some of the greatest scientific accomplishments in human history.

- To understand infectious risks, you have to have good data, carefully sourced and analyzed.

Number 3 is why this week’s non-publication of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) came as such a shock. MMWR is the CDC’s primary way of publishing and communicating important data for public health. It didn’t go out because of a communications pause at federal health agencies issued by the new administration. The gap in publication marks the first time in its more than 60-year history that the CDC didn’t release a new issue.

Want an example of how useful the MMWR is for us ID people? Here’s a good one:

Highlighted in red, dear friends, is the first report of the disease now known as AIDS occurring in five previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles. The text from this account has always struck me as a perfect example of careful but prescient scientific reporting:

The occurrence of pneumocystosis in these 5 previously healthy individuals without a clinically apparent underlying immunodeficiency is unusual … All the observations suggest the possibility of a cellular immune dysfunction related to a common exposure that predisposes individuals to opportunistic infections.

Spot-on accurate. The second MMWR detailing more AIDS cases occurred less than a month later. Remember, these publications appeared 2 years before the discovery of HIV, the virus that causes the disease.

Subsequent MMWR reports on the rising incidence of AIDS, the populations at risk, and the strong epidemiologic evidence for modes of transmission played key roles in figuring out what was happening on a national and global level. We knew even before the virus was discovered that sexual, perinatal, and blood-borne infection were all implicated, and that household and other “casual” contact posed little, if any, risk.

Want more recent examples of infectious threats all reported in MMWR? A partial list:

- SARS

- MERS

- Zika

- Ebola

- Chikungunya

- Candida auris

- Mpox

- H5N1 avian influenza

- Innumerable food-borne outbreaks

- And yes, of course, COVID-19

I put COVID-19 last because I strongly believe this is the primary motivation for the communications pause issued by the new administration. The pandemic was so horrifically disruptive — so traumatic — to our society that we’re still grappling with the best way to deal with it.

And one unfortunate coping mechanism is the urge to scapegoat individuals and organizations for what happened. The CDC and its publications were often in the center of this storm, and some now want to blame them for all that they were unhappy about.

Was CDC perfect? Of course not. But they tirelessly worked to get things right, and reported abundant COVID-19 data on case numbers, hospitalizations, deaths, and vaccinations that we all turned to regularly. To expect, in hindsight, that they would do so infallibly is setting an impossible standard — one no organization, government or otherwise, can meet.

Apparently, the MMWR staff are still at work, so let’s hope that the pause in communication is brief. There always will be infectious threats out there, with H5N1 avian influenza now being foremost on our minds. It’s only through careful and regular reporting of data that we can face these threats responsibly.

January 11th, 2025

Ten Interesting Things About Norovirus Worth Knowing

For reasons unclear to all, we’ve had quite the run (!) on norovirus cases in the United States this winter. Seems like everyone knows someone who’s been taken down by this nasty illness, and this crowd of miserable people includes one of my medical school classmates, a good friend who texted us about her experience.

For reasons unclear to all, we’ve had quite the run (!) on norovirus cases in the United States this winter. Seems like everyone knows someone who’s been taken down by this nasty illness, and this crowd of miserable people includes one of my medical school classmates, a good friend who texted us about her experience.

Thanks for sharing, Diane, speedy recovery!

So here are ten interesting facts worth knowing as you wisely head to the sink to wash your hands again before eating:

1. It is the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis in the world. This chart-topping characteristic of norovirus is probably even more impressive now that the rotavirus vaccine is available, dropping childhood cases from that virus dramatically.

In case you’re wondering, “acute gastroenteritis” just means diarrheal disease of sudden onset that lasts less than 2 weeks and may be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and fever.

2. It was discovered after studying stored stool specimens collected during a community outbreak from 1968. That outbreak involved half (!) the students at a school in Norwalk, Ohio — hence the name, “Noro” gets its first syllable from “Norwalk”. I guess the citizens of that town didn’t want to be remembered for this dismal week.

Before the identification of virus, scientists strongly suspected a transmissible agent for this illness for obvious reasons. Not only was the attack rate so high in that school, but some of the family members of those students (who had not been in the school) came down with a similar illness.

Researchers then conducted some highly disturbing (from an ethical standpoint) human challenge experiments from specimens collected during this same outbreak, proving that it was, in fact, contagious. Can you imagine trying to get studies like this through a human subjects committee today? Awful.

The actual publication of the pivotal paper documenting discovery of the virus wasn’t until 1972, when advances in electron microscopy allowed identification of the culprit critters from four years earlier, shown in this image:

3. Cases of norovirus peak in the winter months. In fact, the illness was once called “winter vomiting illness” due to this seasonal peak, with this generic term used prior to the discovery of the causative agent. Why winter? Humans gather indoors, huddling together against the cold, passing respiratory viruses between each other in the air, and viruses like norovirus in contaminated food, water, and surfaces. Fun times!

It was also called “non-bacterial gastroenteritis” to distinguish it from salmonella, shigella, and other causes of diarrhea that could be diagnosed by cultures. These “non” labels in medicine have always amused me — describing something by what it is NOT. You know, “non-A, non-B hepatitis” before we knew about hepatitis C, or “non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM),” a term still in broad use despite way more NTMs than TMs. Weird.

(I still miss NASH — non-alcoholic steatohepatitis — for fatty liver, an entity that seems to change its name every week.)

4. Infamous sites for norovirus outbreaks include cruise ships, daycare centers, recreational water parks, military barracks, nursing homes, and college dormitories. But especially cruise ships — go ahead, check out that link, I’ll be here when you get back.

… (waiting patiently) …

OK, now that you’ve seen the list of reported cruise ship outbreaks just in the past year, do you still want to take that winter cruise? Fact: any place or situation that people gather in close settings, and where contaminated food, water, and surfaces are hard to control, can trigger these outbreaks. How about particular foods? Oysters are often mentioned, which is no surprise at all, giving me an additional reason to avoid these slimy beasts*.

(*Easy for me to say since I don’t like them. Hardly a sacrifice. Feel very fortunate it’s not chocolate, or pizza.)

5. The incubation period is typically 24–48 hours after exposure. However, this doesn’t mean a person is “in the clear” after a couple of days if they don’t catch it in a household, on a cruise ship, or a dormitory that has active cases, for reasons that will be plainly evident in the next scary facts about the durability and ubiquity of norovirus in our world.

6. While norovirus shedding peaks during the acute illness, the virus can still be detected in stools for weeks in many people, small amounts can cause disease, and it’s devilishly hard to kill. The median time to loss of the virus is a month. Wow. A decent proportion of asymptomatic children shed the virus — nearly half in a study of kids in Mexico.

Plus, it’s an incredibly hardy virus — it resists freezing, heating to 60°C, and is not eradicated by alcohol-based hand sanitizers. I’ve heard this last phenomenon is because of the durable norovirus capsid, versus the much more fragile envelopes in other viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2 and influenza. I’m sure virologists have a much more sophisticated explanation.

One might wonder, reading these facts, why everyone doesn’t get norovirus all the time, or at least once every year. It comes down to those basic principles of infectious diseases, which are host factors (immunity, genetics, stomach acidity), inoculum size (how much virus found its way to you), and luck. Secondary attack rates might be high, but remember that sentinel outbreak in Norwalk — “only” half the students got it.

(For the record, my friend Diane’s husband is doing just fine. So far.)

7. After 1–2 days of utter misery from norovirus gastroenteritis, most people start to improve. During recovery, it’s not uncommon to have a week or so of feeling wiped out as one regains hydration and nutrition, but the general trend is favorable despite some ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms.

As with all infections, the disease is more severe for those at the extremes of age and people who are immunocompromised. For the latter group, illness can be prolonged, lasting weeks or even months, leading to profound weight loss.

8. There is no antiviral treatment for norovirus. Treatment is “supportive”, with the goal of maintaining hydration and getting at least some calories in during the acute phase. Remember, even people with cholera — the most notorious and life-threatening diarrheal disease of humankind — can absorb fluids when given liberally. So hydration is key.

What about during recovery? There’s lots of advice out there on the interweb, with variously recommended diets (e.g., bananas, rice, applesauce, toast — “BRAT” — clear broths, avoiding dairy products and spicy foods, etc.), but the reality is that we don’t have good evidence for any particular diet. I tell patients basically to eat what they want, in moderation, and to listen to what their bodies are telling them. The return of hunger is an excellent sign a person is on the mend.

9. The diagnostic test of choice for norovirus is stool PCR. Many laboratories now do molecular tests first — not cultures — to evaluate the causes of diarrhea. Since it’s so common, norovirus is included in all the multiplex panels that test for multiple pathogens.

The increased use of molecular testing no doubt explains at least in part the increased incidence of this infection. But on the flip side, the vast majority of cases are never diagnosed — so whatever figures we see on incidence are no doubt a massive underestimate.

10. Prevention strategies include frequent hand washing, cleaning contaminated surfaces, and isolation of symptomatic patients. As noted above, despite both pre- and post-symptomatic viral shedding, the highest risk time for transmission is during the symptomatic phase of the illness. Will we ever have a norovirus vaccine? Perhaps, though there are plenty of obstacles.

So that’s 10. Actually way more than 10, see how your subscription brings you added value?

And as an additional bonus, listen to my brilliant colleague Dr. Mike Klompas speak in our postgraduate course. Check out his #1 tip for infection control — for norovirus, it’s gold!

January 3rd, 2025

On the Inpatient ID Consult Service, Oral Antibiotics Have a Rocky Road to Acceptance

Home IV antibiotics are not fun — just look at her face. (Image: Pixabay)

Having just completed a stint doing inpatient ID consults, I came away impressed with three things:

- Staph aureus remains the Ruler of Evil Invasive Pathogens in the hospital setting.

- You can “jinx” a holiday season by saying it’s usually quiet on Christmas. This year it sure wasn’t quiet, hoo boy.

- Some surgeons aren’t ready to accept the evidence about oral antibiotics being just as good as intravenous (IV) for their patients with severe infections.

Note I wrote some surgeons — not all. But with apologies to authors of the POET and OVIVA studies, and in particular to Dr. Brad “Oral is the New IV” Spellberg, who has been a leader in this space, I bring you now a blended version of several conversations I had with surgical colleagues when I recommended oral antibiotics for their patients:

Me: I heard from your resident that you wanted a PICC line for Mr. Smith. Did you see our consult note?

Surgeon: Thanks for following him. No, didn’t read it — what did it say?

Me, not at all surprised that the attending surgeon didn’t read our Masterpiece: We recommended that he go home on trim sulfa, one double-strength tablet twice daily. (I might have said Bactrim. Ok, I did.) The organism is susceptible, and it has excellent oral absorption. That way we can spare him the PICC line and all the risks and hassles of home IV therapy.

Surgeon: This was a very severe infection — I’d prefer we be as aggressive as possible in treating it.

Me: Understood. But there’s literature now showing that oral antibiotics are comparable to and safer than IV. I’m especially comfortable in recommending it when there is a high GI-absorption option like Bactrim, a susceptible bug, and there has been source control, as in this case.

Surgeon: Thanks for sharing that — I’m not up on the ID literature, but this infection threatened to get into the joint (or bloodstream or CNS — it’s a generic conversation). In the OR, we drained frank pus*, and had to copiously** irrigate the site with 3 liters of sterile saline.

(*I always felt bad for people named “Frank” when I hear this expression.)

(**Surgeons frequently use the word “copiously” when they irrigate infections. And how do they decide on the number of liters to use?)

Me: Yes, I understand it was bad. But it sounds like you got it all — that’s probably the most important thing. Another thing, he’s taken Bactrim before, and we know he tolerates it well.

Surgeon: Maybe use orals for a milder infection, but not for an infection this severe. I told him after the surgery he’d be going home on IVs. If we use oral antibiotics and it fails, I’d feel bad we didn’t attack this as hard as possible with IV antibiotics.

Me: Ok, we’ll set up the home antibiotics.

Surgeon: Great, thanks so much. Really appreciate your help.

Me: No problem. He’ll go home on 6 weeks of IV colistin.

(That’s an ID joke, ha ha. It really was ceftriaxone.)

A few comments about this exchange.

- It’s entirely friendly. We both want what’s best for the patient.

- The surgeon has already made up his mind before consulting us that IV is preferred over oral antibiotics.

- There is deep anxiety about oral antibiotics not being “aggressive” enough with a “severe” infection, with the concern about an error of omission rather than commission. Meaning, a bad outcome by doing less outweighs concerns about a bad outcome by doing more, which is why I bolded this sentence, and repeat it here: “If we use oral antibiotics and it fails, I’d feel bad we didn’t attack this as hard as possible with IV antibiotics.”

This last point gets to the core of this debate. Surgeons, who by their very nature are quite active in their day-to-day practice, may not comfortable with what they consider a less invasive approach. Intravenous antibiotics are more challenging, more intensive, typically reserved for inpatients or critically ill people, hence (they think) they must be better.

This is a particularly tough nut to crack. And I get it — if an infection is severe, don’t we want to treat it as aggressively as possible?

The problem with this line of thinking is that it ignores good clinical evidence (including randomized trials and well-done observational studies); it does not factor in the risks, hassles, and cost of IV therapy; and it forgets the important principle Brad often cites, which is that the bacteria don’t care how the antibiotic got there — just that it got there.

In some ways, we’ve fostered the surgeon’s view by taking on the management of home IV therapy — often called Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy, or OPAT — as a core responsibility of us specialists in Infectious Diseases. After all, who knows antibiotics better than we do?

But this has insulated them from the problems. If we had each surgeon manage OPAT for their patients, it would open their eyes about misplaced monitoring labs, clotted and infected lines, upper extremity DVTs, failed home deliveries of medications, confused care providers at home, capricious vancomycin levels, and miscellaneous other mess-ups that are an unwelcome part of home IV therapy.

I have a hunch that if Dr. Orthopod P. Neurosurgeon had to manage these and myriad other OPAT issues, they’d be quite willing to consider an oral option if we told them a good one existed.