An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

September 18th, 2016

Ten Years After Landmark HIV Testing Guidelines, How Are We Doing? Specifically in Emergency Departments?

In the late 1990s, a patient was admitted to our hospital with HIV-associated PCP. He had advanced AIDS, a CD4 cell count < 100, and was sick enough to require a temporary stay in our ICU.

In the late 1990s, a patient was admitted to our hospital with HIV-associated PCP. He had advanced AIDS, a CD4 cell count < 100, and was sick enough to require a temporary stay in our ICU.

Those clinical details aren’t so remarkable — “late” diagnoses of HIV still happen, and happened even more back then. What’s remarkable is what happened to him before he got admitted.

As an (early) freelance web designer, he had no medical insurance, and received his infrequent care through an emergency department at a hospital near his apartment. He had gone there around a month before we admitted him with cough and weight loss; no pneumonia was seen on his CXR at that point. He told the doctor who saw him that he was worried he had AIDS since he was a gay man and hadn’t been tested in many years.

According to the patient, the doctor there told him that he was right to be concerned, but that the policy of the ED was that they could not do HIV tests. He urged him to see a primary care doctor soon after discharge from the ED to get this checked.

Never happened — he didn’t have a primary care provider. His illness smouldered along for a while, until it became severe enough that he was admitted here with pneumonia. He said repeatedly that if he knew he was HIV positive, then he would have sought care much earlier.

When I told this story to someone from our ED way back then, they said the same thing — that it was a “policy” (unwritten, but widely agreed upon) that they should not send HIV tests, even if they clinically suspected a patient had AIDS.

One of our current Emergency Medicine doctors, Kelli O’Laughlin, explains:

Historically there is a sentiment in emergency medicine that energy and resources in the emergency department should be reserved for dealing with urgent medical conditions rather than on diagnosis of chronic medical issues. Additionally, emergency medicine clinicians have avoided testing patients in the ED for HIV because of the concern results will return when the patient is no longer in the ED. This can make it challenging to share results with the patient, which can expose physicians to legal risks. Other barriers to HIV testing in the ED include lack of provider knowledge and comfort with pre-test counseling and post-test counseling.

Well a lot has changed with HIV testing since the late 1990s, most notably the landmark CDC HIV testing guidelines, issued almost exactly 10 years ago today. (Happy 10th Birthday!) Those guidelines have been critical in reducing the proportion of people in the USA with HIV who are unaware of their status (now around 10-15%), allowing those with HIV to get life-saving treatment before getting AIDS-related complications, and preventing further HIV transmissions.

While the guidelines are often cited for recommending an HIV test for most US adults and removing the requirement for written informed consent, just as important was that they specified where HIV testing should take place — namely “all health-care settings.” If that’s not clear enough, this is:

The recommendations are intended for providers in all health-care settings, including hospital EDs [emphasis mine], urgent-care clinics, inpatient services, STD clinics or other venues offering clinical STD services, tuberculosis (TB) clinics, substance abuse treatment clinics, other public health clinics, community clinics, correctional health-care facilities, and primary care settings.

I don’t think it’s an accident that hospital EDs are listed first among health-care settings in the CDC testing guidelines. As noted here:

HIV disproportionately affects populations that are likely to be without a regular source of care or have a history of barriers to care, which may contribute to delayed diagnosis and further transmission of HIV. Many are dependent on the public sector for the financing and delivery of their care. … Consequently, EDs — whose patients include large numbers of underinsured and uninsured — are likely the only source of health care for many people with HIV or at risk for HIV.

And what about guidelines about HIV testing specifically from the American College of Emergency Physicians? They’re in agreement, and have been since 2007.

This post is undoubtedly “preaching to the choir” — who reads an ID/HIV blog, after all? — but the main reason I’m writing it is not just because of the impending 10 year anniversary of the CDC guidelines, but to underscore just how difficult the culture shift has been in certain EDs around the country.

Including, ahem, ours. And, since misery loves company, the situation is even worse at one of our “partner” hospitals (which will go unnamed, but is also commonly abbreviated with three letters).

Writes Kelli:

Despite CDC recommendations for HIV screening in health-care settings, in our own emergency department, ironically, we do not have processes or systems in place to make HIV testing efficient. We cannot ensure that abnormal results will reach the patient. I experienced this problem over a year ago when a patient I tested for HIV was discharged from our emergency department observation unit without receiving his/her abnormal result of the initial HIV screening test. Fortunately we were able to locate this patient shortly after. Motivated both by the gap between CDC recommendations and our practice, as well as this individual case, I worked with colleagues to establish the HIV Testing in the ED Committee.

I’m confident that with Kelli’s leadership, it will become a reality soon. Already I can tell that our ED clinicians are ordering more HIV tests, and we’ve been collaborating with them to ensure that any positive results are given an expedited evaluation by an ID doctor.

What’s the situation where you work?

September 11th, 2016

Poll: More on Morgans, and Vote on Your Favorite Cartoon Caption

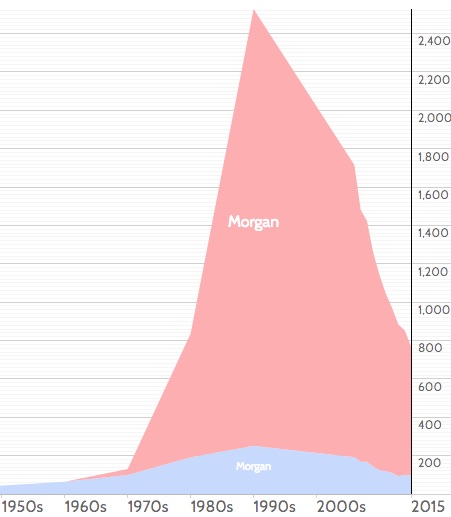

During my last post on the new HIV testing algorithm, I mentioned that I’d recently met a doctor named “Morgan” for the first time. I also provided actual data why this might be an unusual name for a doctor today, but, rarity notwithstanding, we should anticipate more examples of “Morgan —-, MD” soon.

During my last post on the new HIV testing algorithm, I mentioned that I’d recently met a doctor named “Morgan” for the first time. I also provided actual data why this might be an unusual name for a doctor today, but, rarity notwithstanding, we should anticipate more examples of “Morgan —-, MD” soon.

At the end of the post, I wrote: “And if there are any other doctors named Morgan out there, I look forward to hearing from you.”

The topic prompted a curious series of emails between certain esteemed editors at NEJM Journal Watch and me. Below, a (heavily edited and augmented, but bones are unchanged) version for your perusal:

Esteemed Editor #1 (EE#1): Hey, did you hear from any doctors named Morgan?

Me: Not yet. But in 10 years — there will be plenty! They will be banging down my door! Look at that graph! It really does seem to be a “generational” kind of name … You must know plenty of Morgans. [She’s much younger than I, hence my comment.]

EE#1: I personally know ZERO Morgans.

Me: Hey, how old are you? I’m figuring that most Morgans are in their late-20s-30s around now. My nephew is getting married this weekend, he’s around 30. Bet he knows some Morgans.

EE#1: Almost 46!!!! [Note the 4 exclamation points.] I could have a kid named Morgan. But all of my imaginary kids are named something else.

Esteemed Editor #2 (EE#2), who has been cc’d on these critical emails, but thus far is playing it cool: Are you implying that you think we are in our 20s? If so, we will love you forever. The only Morgan I know is the one from the Mindy Project.

Esteemed Editor #3 (EE#3), who’s also been cc’d and now can’t resist weighing in: Morgan Fairchild… not a millennial. Born in 1950! [The internet is cruel.]

EE#1: Yeah, pretty much the only one I’m familiar with.

Me: Morgan Freeman too, though I think of Morgan Fairchild as the true pioneer in the Morganization of the USA. And let’s face it, most of the young Morgans out there are females.

EE#1: Right, it’s a unisex name. But more XX than XY recently.

EE#2: I can’t believe I forgot about Morgan Freeman! And he won an Academy Award, didn’t he?

Me: It was for The Shawshank Redemption. [I don’t really know this, but state it very confidently, at least if there’s an email equivalence of confidence. Guys love “The Shawshank Redemption.” And I’m counting on the fact that we’re all so “busy” — as evidenced by these emails — that they’ll never fact-check me. Oh well.]

EE#1: Wrong! Per Wikipedia: “Freeman won an Academy Award in 2005 for Best Supporting Actor with Million Dollar Baby (2004), and he has received Oscar nominations for his performances in Street Smart (1987), Driving Miss Daisy (1989), The Shawshank Redemption (1994) and Invictus (2009).” So nominated for Shawshank, but didn’t win. In fact, nominated for a lot!

Me: Did you fact-check Wikipedia? [I got no response to that one.] Our readers would think I’d completely lost my mind if I wrote another blog post about doctors and Morgan, but there just might be enough material here.

EE#1: Well, I’m the blog manager for your blog (and technically I report into EE#2 for this portion of my job). So, she might object to your Morgan-obsession. : ) I’ll defer the final decision …

EE#2: No objection from me! Make it hilarious. [That will be your assessment. I’m doing my best!]

EE#1: Maybe do a two-topic post, in which Morgan is only one of the topics.

Me: Actually, I was just kidding.

EE#1: Darn, I wish you were serious! Have a nice evening, all!

Ahem.

ID doctors, of course, are probably wondering, in our geeky way, about whether this all started with Morganella morganii, which is possibly fueling my obsession. Double Morgans, after all! And there’s a pretty famous comic with a Dr. Morgan name (see above picture), but his first name is Rex. Emphatically not Morgan.

On the subject of comics, it’s time to vote on your favorite caption for our last cartoon. After culling through the entries and submitting them to the usual rigorous testing, we’ve arrived at 3 top candidates for this fine drawing. Please vote!

September 4th, 2016

The Most Common Question About the New HIV Testing Algorithm, Answered

A primary care doctor in the Boston area recently emailed me this question:

A primary care doctor in the Boston area recently emailed me this question:

Hi Paul,

A 28yo woman had a positive 4th gen +Ag/Ab assay, but a negative HIV-1/2 differentiation assay and negative HIV viral load. She had no signs of acute HIV, but is not using condoms with her partner, whose HIV status she doesn’t know. We repeated the test yesterday and she is again Ag/Ab+, the remainder of the test is pending. If we get the same results again, would you try to get a Western blot?

Thanks,

Morgan

[Not her real name, but I did just meet a doctor named “Morgan” for the first time, so feel compelled to comment here. If you look at this name popularity graph, I guess we have an explanation for the rarity of this name among MDs to date. Did you know Morgan was the 30th most common girl’s name in the USA during the 1990s? So expect more Morgan MDs soon!]

“Morgan’s” question has come up numerous times since the new algorithm kicked in, and it reflects a misunderstanding of what the newer tests can and can’t do.

Remember, the big advance in moving from the 3rd to the 4th generation screening test was the addition of p24 antigen to the sensitive ELISA antibody. This shortens the window period from HIV acquisition to a positive screening test by about a week.

The second big change is that the confirmatory test is now a differentiation assay, an antibody test that tells us if the person has HIV-1 or HIV-2 — the Western blot couldn’t do that. If it’s negative, an HIV RNA (viral load or other nucleic acid test, NAT) is recommended, since the screening test (with its antigen component) is more sensitive early in disease than the differentiation assay. Importantly, the Western blot — may it R.I.P. — offers no advantage in sensitivity over the FDA-licensed differentiation assay (in fact, it’s a bit worse), so won’t be of help in these cases.

However, if the HIV RNA is negative, then we’re dealing with a false-positive screening test, and this is exactly the scenario in the email. For relatively low-risk patients, this is a far more common explanation for the positive 4th generation screen/negative differentiation assay pattern than true acute HIV infection, just as it was for a reactive ELISA with negative Western blot.

How much more common? In this review (pages 34–36) by the primary architect of the algorithm, Bernie Branson, we get some numbers:

The specificities of 4th generation HIV assays are >99.6% — which means that as many as 40 per 10,000 test results may be false-positive. In most populations of persons testing for HIV, the prevalence of acute HIV infection is 2 per 10,000 persons tested or less. Thus, the frequency of false-positive immunoassay results usually far exceeds the prevalence of acute HIV infection.

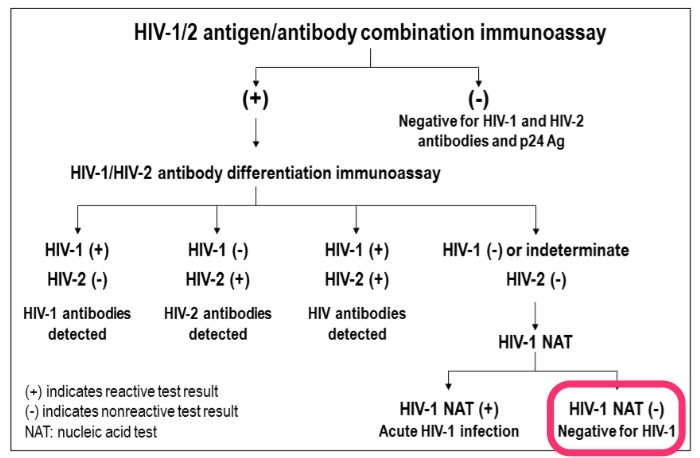

For those who prefer all this stuff explained graphically, here’s the key figure from the latest HIV testing guidelines; I’ve highlighted this case’s results in bright fluorescent pink:

To summarize:

- The 4th generation screening test shortens the window period after HIV acquisition.

- The differentiation assay tells us if the person has antibodies to HIV-1 or HIV-2.

- In screening test positive/differentiation test negative cases, the next step is an HIV RNA (or other NAT).

- Most (but not all) will have a negative HIV RNA, and therefore don’t have HIV.

In other words, false-positive screening tests will continue to happen — even with the new algorithm.

Thank you very much for your attention, and enjoy this amazing video, which must have taken its creator many, MANY hours to complete. Wow.

And if there are any other doctors named Morgan out there, I look forward to hearing from you.

(H/T to IMS for the video, though it looks like many millions of people have beaten us to it.)

August 27th, 2016

ID Cartoon Caption Contest #1 Winner — and a New Contest for the End of Summer

All blogs worth the price of admission have a sidebar, and this one is no exception.

Critical components include (but are not limited to) the following:

- The Option to Subscribe — Go ahead, you know you want to. It’s right over there to the right. Just enter your email address and click subscribe — no username, password, or two-step verification required. Then, kind of like colonization resistance, the notifications you’ll get of a latest post here will help crowd out those dubious invitations to conferences in China, Dubai, or Malaysia, the requests to submit papers for the The Journal of Infectious and Non-Infectious Diseases, and the people who are trying to sell us CRISPR reagents.

- The Search Box, where you can enter diverse topics such as “Should I curbside ID about whether to give the rabies vaccine?” or “Why does he hate the term HAART?”

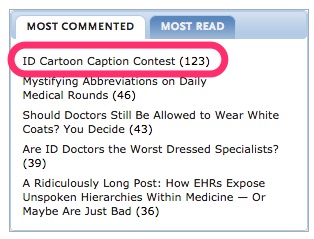

- The Most Popular Posts list, which here is called, “Most Commented,” with another tab for “Most Read.”

In case it wasn’t obvious enough, I’ve highlighted that the first ID Cartoon Caption contest drew quite a response. If we add in entries that were sent to me directly via email, there were well over 200 submissions. Not bad for a debut performance.

Anyway, here’s the winner of ID Cartoon Caption Contest #1:

The winner was Dr. Michael Dantzer, who has kindly given me permission to use his real name (I assume it’s his real name). As promised, he gets a free lifetime subscription to this blog and, of course, lasting fame and fortune.

He also sent me a nice note praising my excellent sense of humor in picking his entry as a finalist. It should be noted, however, that the selection of his entry as a finalist relied not so much on my subjective sense of what’s funny, but a highly complex algorithm that includes not only scientifically validated humor criteria but also gas liquid chromatography and multiplex PCR.

Anyway, it’s high time for a new contest. Summer is about to end, Labor Day cookouts loom, and we must be vigilant to the ever rising threat of both foodborne pathogens and carcinogenic heterocyclic amines:

Go at it. Put your entries in the comments section (preferred), on my Twitter feed, or email it directly to id.caption@yahoo.com.

(Drawing by Anne Sax, of course.)

August 19th, 2016

Pre-Vacation Scramble

If you search “Are vacations good for you?,” you’ll find overwhelming support for time off.

If you search “Are vacations good for you?,” you’ll find overwhelming support for time off.

It’s as if journalists and the travel industry were in cahoots, together trying to urge us to take vacations, the longer or more frequent the better.

Hey, I get it. Time to reconnect with family and friends, to recharge those batteries, to get a fresh perspective on both work and life, to explore new challenges … yadda yadda yadda. The list of benefits is so long that it seems cliched to write them, so I’m going to stop there.

But you know what? That pre-vacation scramble to make sure things are settled just right before you go — that’s no fun at all.

And if you’re a typical doctor/nurse/PA, you probably are plenty detail oriented. ID doctors in particular will know that “detail oriented” barely begins to describe their obsessive attention to the minutiae of their everyday practice and life — and that includes establishing whether the culture was positive for M. abscessus or M. abscessus subspecies bolletii, making sure the out-of-office message conveys just the right information about when/where/how long that time away will be, and whether they’ve left clear directions to the person they’ve hired to feed the cat.

After all, how can you go on vacation if you’ve still not figured out how to get Mrs. Smith’s vancomycin level between 15 and 20? Or informed Mr. Jones that the last viral load that came back at 23 copies/mL (instead of “not detected,” as usual) is no cause for alarm?

The Big Secret, of course, it that nothing is ever completely settled, whether we go on vacation or not. So we may as well take some time off, which is what I’m about to do (hence this post).

But it also gives me a chance to share this funny (at least I think it’s funny) text, sent to me by an ID colleague who runs the Antibiotic Stewardship Program at another hospital. For non-ID readers out there, these programs (generally run by ID doctors) aim to guide clinicians to the most rational use of antibiotics, in particular to avoid inappropriate use of broad-spectrum therapy, reducing the risk of bacterial resistance (a very bad global problem).

He was scurrying around trying to finish up some work before leaving on vacation, and received this series of messages from a hospitalist who was trying to consult him one last time before he left:

Safe to say he responded to her at 9:11!

August 15th, 2016

Just Wondering: Quick ID Questions to Ponder On a Hot Summer Day

On a lazy, brutally hot summer day, here are some more “quick questions” to think about as you hope for a cool breeze to bring relief from the stultifying (love that word) heat:

On a lazy, brutally hot summer day, here are some more “quick questions” to think about as you hope for a cool breeze to bring relief from the stultifying (love that word) heat:

- How soon will we be able to look back at contact precautions for MRSA and VRE and laugh at our folly?

- Are we again recommending antibiotics after incision and drainage of uncomplicated skin abscesses? Hard to keep track of this one. Maybe because there’s no right answer for everyone.

- What’s the best shorthand/abbreviation for “Fourth-Generation combination HIV-1 antigen/HIV-1/2 antibody immunoassay?” Boy I’m tired of writing that. How about, “HIV screening blood test” (with all the rest of the stuff implied)?

- What proportion of those with a diagnosis of both Lyme and bartonella actually have neither?

- If dalbavancin and oritavancin weren’t so expensive — say, $500/course instead of $3000-5000 — how much would we use? (I think a lot.)

- If Sporothrix schenckii had a different name, would such a high percentage of clinicians remember its association with rose thorns? “Sporotrichosis” just sounds like a disease you get from something sharp and prickly. Oh, and sphagnum moss (not sharp and prickly) and cats (could be) are also sources, for you trivia buffs.

- What percentage of our ID consult notes are actually read by surgical consultants? Regardless — what do they think of them? Especially the really long ones.

- In community acquired pneumonia severe enough to require admission, how often are antibiotics stopped after a specific viral infection is diagnosed using molecular studies? Seems to work in kids and adults for “respiratory infections”, but for admitted patients with pneumonia? Unclear, but I’d still value the information.

- Will anyone ever figure out what is causing that outbreak of Elizabethkingia anophelis in the Midwest?

- Why isn’t there more drug development for non-tuberculous mycobacteria? Gosh darn it, there’s a clinical need here. Hey there, you medicinal chemists, lab-based ID scientists, and PhDs, get on it!

- The HIV primary care guidelines recommend “anal pap tests” as a screen for anal cancer — but how often should they be done? Can anyone in good conscious suggest a test be done annually (for example) that hasn’t yet been proven to prevent cancer or improve clinical outcomes?

- Will there ever be a flu vaccine you don’t need to repeat every year? I can dream, can’t I? Or lower hanging fruit — a better mumps vaccine?

- Who will figure out how to make an ID-approved, well-done hamburger that doesn’t taste like charred sawdust?

- In the sofosbuvir combination treatments for HCV, which of the two drugs should be said first? I’ve been saying “LDV-SOF” (spelling out the “LDV”) and “VEL-SOF” (saying “VEL”), but have noticed all kinds of variations. You could do the brand names, but please. The direct-to-patient ads for LDV-SOF are almost as common as those for razors and pickup trucks.

With all the controversy about the Rio Olympics, Zika, and contaminated water, is there any ID-related sports story more bizarre than the leptospirosis-poisoned tennis player? Hey — it gives me first-time chance to link the British Sun, that fine example of responsible journalism. Am sure they would welcome the web traffic from here, though perhaps be a bit surprised to get it.

With all the controversy about the Rio Olympics, Zika, and contaminated water, is there any ID-related sports story more bizarre than the leptospirosis-poisoned tennis player? Hey — it gives me first-time chance to link the British Sun, that fine example of responsible journalism. Am sure they would welcome the web traffic from here, though perhaps be a bit surprised to get it.- How many of those “antigen-positive, toxin negative, PCR positive” patients treated for C diff really don’t have C diff at all? If you don’t know what I’m talking about, read this.

- Will I ever remember — without struggling to come up with the specific name — that Haemophilus aphrophilus is now Aggregatibacter aphrophilus and Aggregatibacter segnis? Some facts just might be for nimble young minds only, but am making this one my personal obsession.

- Will TAF/FTC work for PrEP? Good question for a clinical trial!

- Is there anything more predictable than 1) a scientific paper finding bacteria on some household item, then: 2) the media getting all grossed out by the research, minimal clinical implications notwithstanding? Latest example — your coffee maker drip tray! Ewww!

- How long before there’s a reported antibiotic shortage do the manufacturers know it’s coming? I’m thinking about you, cefepime makers! It’s not as if demand for this drug was low.

- How many “First Zika Transmission in [insert Southern US City here] Reported” will we see this year? And how many incredibly difficult to carry out pregnancy recommendations?

- When will IGRAs completely replace tuberculin skin testing? Not saying that they are more accurate, just that they’re so much easier. Might be a downside in the healthcare screening setting — too many false-positives over time.

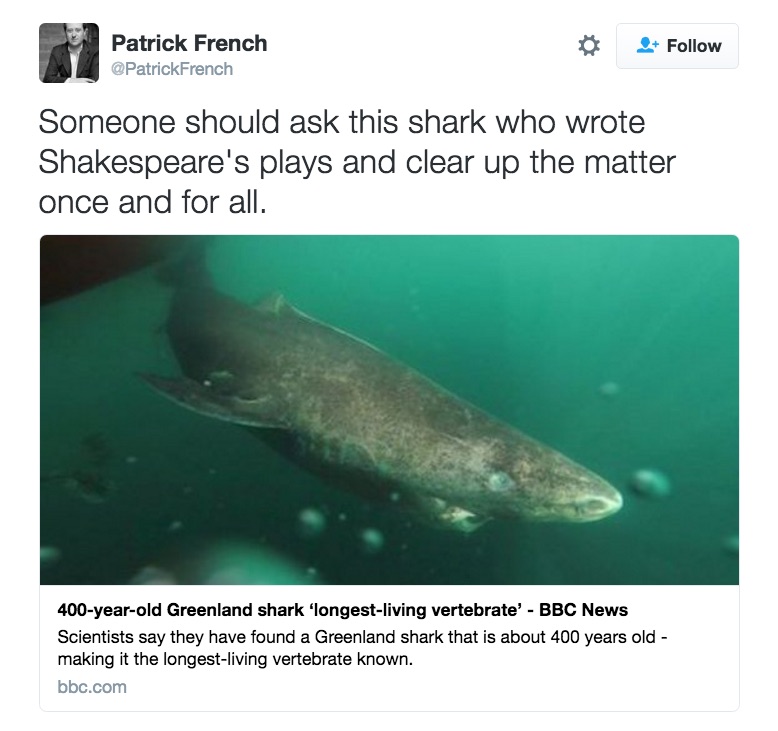

That’s enough for now. Need to stay cool … just like the 400-year-old shark, pictured above.

And it’s not easy being funny in 140 characters. But some people succeed brilliantly!

August 6th, 2016

Fishy, Fishy, Fishy, Fish!

I received this exciting offer recently:

Re: Fish Disease — Manuscript Invitation

Dear Dr. Paul E Sax,

Greetings for the good day!

We gladly invite you and your colleagues to contribute the articles on the topic Fish Disease in Johnson Journal of Aquaculture and Research of Johnson Publishers.

During our past two volumes, we had an excellent and fruitful cooperation, especially with our Editorial Board members.

We hope this volume will be interesting, with the presence of articles from Eminent personalities like you.

We are looking forward to receive and review your papers. For any information needed, please feel free to contact via e-mail: aquaculture@johnsonpublishers.international

Thank you for your attention towards this letter.

We are happy to announce that this is the 2nd year for this Journal. It will be a great honor for us and an excellent opportunity for you to share your newest scientific work on the field of Johnson Journal of Aquaculture and Research related issues in our international scientific review.

Regards,

Jennifer Griffin

Johnson Journal of Aquaculture and Research

Johnson Publishers

9600 Great Hills

Trail # 150 w

Austin, Texas

78759(Travis County)

E-mail: aquaculture@johnsonpublishers.international

What an opportunity! Here’s my response:

Dear Ms. Griffin:

Thank you so much for reaching out to me about submitting a paper to the Johnson Journal of Aquaculture Research. I have long been an admirer of your journal, and am proud to say I was one of the inaugural subscribers; I eagerly await each issue with great excitement.

Thank you so much for reaching out to me about submitting a paper to the Johnson Journal of Aquaculture Research. I have long been an admirer of your journal, and am proud to say I was one of the inaugural subscribers; I eagerly await each issue with great excitement.

Your invitation today was propitious, since, as luck would have it, my research team and I have just completed a major study on the topic of Fish Disease. It should be right in your journal’s wheelhouse, as they say.

(Since you are based in Austin, Texas — Travis County, as you note — you no doubt understand that wheelhouse expression.)

Anyway, I ramble. Let me get right to the point — we think our study is groundbreaking. If we don’t win a Nobel Prize in Fish Disease (there is one in Fish Disease, right?), we’ve been robbed.

Here’s the abstract:

Background: Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (commonly known as freshwater white spot disease, freshwater ich, or freshwater ick) is a common disease of freshwater fish in home aquariums. It can cause white spots, clamped fins, and reclusive behavior due to severe embarrassment, poor little things. The optimal treatment is unknown. Methods: We randomized household guppies with moderate-severe ick to standard of care treatment (whatever that is) or a chlorhexidine whole body wash. Outcomes were assessed by trained fishologists blinded to study arm, using validated ick instruments and quality of life scores (CDC HRQOL-14, SF-36, WHOQOL-BREF, and some other letters put together that sound impressive). Results: After informed consent was obtained (at least to the extent possible from a fish), 6 guppies were enrolled, 3 in each treatment group. Baseline characteristics seemed roughly comparable, but how would we know (they’re just little guppies, after all). On a 100-point ickiness scale, the chlorhexidine washed guppies scored 22.4 International Ick Units (IIUs), vs 57.8 IIUs for the standard-of-care group (p < 0.0000001 — wow, that’s significant, isn’t it). Quality of life measures also favored the chlorhexidine-treated group (“I’m just happier,” one guppy said). Conclusion: For common aquarium guppies suffering the embarrassment of freshwater ick, chlorhexidine whole body wash is superior to usual treatment. Prevents MRSA, too.

I hope you will consider our study carefully. Eminent personalities like us ponder long and hard about the best venue for such important research. Your email was perfectly timed.

Sincerely yours,

Dr. Paul E. Sax

Henry Limpet Professor of Ichthyologic Ick

University of Travis County

(Part of an occasional series, I guess. H/T to Monty Python for the title.)

July 31st, 2016

Summertime Pre-Olympics ID Link-o-Rama

If you’re wondering what to do between the end of the presidential conventions, the baseball trade deadline tomorrow, and the start of the Summer Olympics, here are a few ID/HIV related items to contemplate:

If you’re wondering what to do between the end of the presidential conventions, the baseball trade deadline tomorrow, and the start of the Summer Olympics, here are a few ID/HIV related items to contemplate:

- Non-travel related Zika arrives in Florida. Start getting used to seeing more of that obscure word “autochthonous”. The uncertainty was not whether Zika cases would occur here — that was inevitable — but when they would happen. Most experts still don’t think we’ll have a Brazil-sized outbreak; nonetheless, other southern states will have cases, and until we have better and more widely available tests, there will be tremendous anxiety in all affected regions. Meanwhile, we ID doctors continue to wonder why it’s so hard to get consensus on emergency funding for ID outbreaks.

- Your nose may harbor antibiotic-producing bacteria. Tons of media attention for this story! Maybe because that old favorite of ID rounds, Staph lugdunensis, is kindly providing the anti-MRSA agent, something the authors call “lugdunin”. (Not to be confused, of course, with laudanum.) This is yet another example of “colonization resistance”, a term of increasing relevance all the time.

- Training ID fellows to do penicillin allergy skin testing in hospitalized patients improved antibiotic use. It’s always such a relief to remove penicillin allergy from a patient’s problem list, especially since it’s a label usually based more on family lore than reality. (“My mother always told me I was allergic”, say even adults of advanced age.) This novel ID (not Allergy) -driven program yielded impressive implementation and outcomes data — more than half the patients who underwent skin testing then had optimization of their antibiotic regimens (narrower spectrum, more cost-effective).

- Cefazolin is as good (if not better) than nafcillin for MSSA bacteremia. Yet another study supporting the benefits of cefazolin over nafcillin (or oxacillin). The data from this and prior papers make it abundantly clear that this easier, safer treatment (cefazolin) should be chosen in most cases once patients are stable. We really do need a randomized clinical trial comparing cefazolin vs nafcillin/oxacillin for up-front therapy — who’s going to pay for it?

- FDA labels on fluoroquinolones updated to include “disabling and potentially permanent side effects of the tendons, muscles, joints, nerves, and central nervous system.” It is truly remarkable how far these drugs have fallen from their perch just a few years ago as the “Cadillac of Antibiotics” (am quoting a patient of mine commenting on ciprofloxacin — I guess even the car reference is a bit stale). It is critical to have more data on the frequency and risk factors for these rare but serious quinolone side effects, as this class of drugs is still quite useful.

- Treatment of acute HIV lowers the HIV “reservoir setpoint”, at least as measured by cell associated HIV DNA. These are the strongest data to date on this potential benefit of very early HIV treatment. I write “potential” benefit since such early treated patients are those most likely to be amenable to HIV cure strategies.

- A “microbiome” treatment for C diff failed to prevent recurrences better than placebo. Called SER-109, it is a “rationally designed ecology of bacterial spores enriched from stool donations obtained from healthy, screened donors.” It just could be that the natural stuff (ok, poop) has some unquantifiable healthy factors that just can’t be captured artificially. You know, kind of like real food vs extracted micronutrients given separately as pills, shots, whatever. Real food always wins.

- Elimination of routine contact precautions for MRSA and VRE did not increase the rate of these infections. It’s a retrospective study, and the hospitals also increased chlorhexidine bathing, but still –hospital-based clinicians are eagerly awaiting the moment when the futility of contact precautions is proven, and subsequently abandoned. Here’s hoping.

- This “patient simulation” expertly guides outpatient providers on how to avoid prescribing unnecessary antibiotics. Note that it tries to do so without making your patients mad at you, a tough challenge. One of our superb social workers is a huge fan of motivational interviewing — she most definitely would approve.

- Guidelines for treatment of coccidioidomycosis updated. If you live outside of a cocci-endemic area — which emphatically includes all of us who work in New England — good treatment guidelines and the email address of the lead author, John Galgiani, are essential items. Always makes sense to get help from those who see a lot of this sometimes serious fungal infection.

- Antibiotics for pneumonia can be stopped after 5 days, provided patients are stable and fever-free for 48 hours. Two reasons why short course therapy works: 1) The immune system is probably doing most of the work once patients start to improve; 2) Many cases of CAP aren’t caused by bacteria anyway!

- A bill added to the Massachusetts state budget would mandate insurance coverage for long-term antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease. As I’ve written before, the optimal therapy for patients with residual symptoms after Lyme treatment is anything but clear. Seems legislating coverage in an area of such clinical controversy is not the right move, and Gov. Charlie Baker fortunately agrees.

Hey, World Hepatitis Day was this past week (specifically, July 28). Do these “Diseases Awareness Days” (I made that term up) actually do anything? I can understand the motivation, but the cynic in me says that they are just preaching to the already aware. Maybe somebody has done a study of their usefulness?

Oh, and the day after was National Lasagna Day.

(Photo source: Library of Congress)

July 24th, 2016

Really Rapid Review — AIDS 2016, Durban

The International AIDS Conference returned this year to Durban, South Africa, where it was famously first held in 2000. At that time the HIV epidemic was exploding in South Africa; funding for HIV treatment was essentially non-existent, and there was ongoing HIV denialism quite openly from some very influential figures in the South African government (including the President). Globally, fewer than 1 million people were receiving antiretroviral therapy, hardly any of them in Africa.

The International AIDS Conference returned this year to Durban, South Africa, where it was famously first held in 2000. At that time the HIV epidemic was exploding in South Africa; funding for HIV treatment was essentially non-existent, and there was ongoing HIV denialism quite openly from some very influential figures in the South African government (including the President). Globally, fewer than 1 million people were receiving antiretroviral therapy, hardly any of them in Africa.

Encouragingly, according to this UNAIDS report, the number being treated today is 17 million — with, incidentally, the largest number in South Africa. Yes, this 17 million is only half the number who need treatment, but this is still extraordinary progress. HIV-related deaths started steadily declining in 2005, a trend one can hope will continue.

OK, on to a Really Rapid Review™ of the conference. It’s organized by prevention, treatment, complications, and whatever else happened to have caught my eye; I welcome suggestions for what I’ve missed (undoubtedly something important) in the comments section.

- In the open-label extension of the IPERGAY study, the efficacy of the “on demand” PrEP was 97%. There was only 1 seroconversion out of around 300 participants, this in a patient with no detectable blood levels of tenofovir. The average number of pills taken/month was 18, so it doesn’t quite answer the question of whether this strategy works for people whose “on demand” is quite a bit less frequent than in the study participants (say, once monthly or even less often).

- In 1013 serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda, 6 months of PrEP to seronegatives and ART to the those with HIV reduced HIV incidence 95% compared with historical controls. All 4 incident HIV infections occurred in people not taking PrEP, or with a source not on ART (outside the couple). Interesting question — should we really be recommending PrEP indefinitely to HIV negative people in monogomous serodiscordant relationships if their partner has virologic suppression? Our guidelines say so, but I’m dubious.

- Nearly 80,000 people have been prescribed PrEP in the USA, with over a 700% increase since 2012. The really sharp upward inflection started after presentation of the PROUD and IPERGAY studies in 2014, and not surprisingly occurred mostly in men. Fascinating geographic distribution: New York state with the largest number of scripts, then California; Massachusetts with the highest rate of prescribing based on population. Southeast USA — where HIV incidence is highest — unfortunately lags way behind, clearly a practice gap worth improving.

- A study of PrEP in at-risk 15-17 year old male adolescents showed just how hard this population will be to reach. The study pre-screened nearly 3000 peole to find 260 eligible. 152 refused participation. 108 were screened. Finally, 79 enrolled — and then 32/79 (40%) stopped the study before 48 weeks! Adherence also sharply declined, and HIV incidence was 6.4/100 person/years (that’s very high). Clearly some other strategy needed.

- The risk for drug resistance with PrEP in 5 clinical trials was only 0.05%. Even when inadvertently prescribed during acute HIV, the risk is “only” 37% — lower than I would have expected. It’s mostly M184V, of course — a mutation that would be easy to salvage.

- Could the vaginal microbiome partially explain the lower efficacy of PrEP in women? (Link is to several presentations.) Seems that Gardnerella and Prevotella spp may inactivate tenofovir more than lactobacilli. If this isn’t an ID nerd’s factoid, I don’t know what is.

- A vaccine strategy demonstrated impressive “correlates” of HIV protection. Results will allow a large efficacy study (HVTN 702) to go forward in South Africa. For the record, the strategy is called “clade C ALVAC-® (vCP2438) and Bivalent Subtype C gp120/MF59®”. These vaccine researchers sure do have their own special language.

- The PARTNERS study of “condomless sex” (published last week in JAMA) will follow MSM participants through 2018. The rationale is to provide a more precise estimate of the risk of acquiring HIV in this highest risk group, a very important remaining question.

- In a randomized study of immediate (same day) vs standard of care timing of ART in Haiti, early therapy improved survival. Important definitions: “immediate” = same day as HIV diagnosis; standard-of-care = only 21 days later, with counseling visits before then. This is a remarkable result, especially since 1) patients with active OIs were excluded; 2) the number of clinic visits was the same; and 3) the effect was so great a DSMB stopped the study early. Seems that starting ART right away improves engagement in care, and all of those “are they ready to start ART?” questions have been answered: YES THEY ARE.

- In the ARIA study, ABC/3TC/DTG was superior to TDF/FTC + ATV/r in treatment naive women. There were both fewer discontinuations for adverse events and fewer virologic failures in the ABC/3TC/DTG arm. The integrase-first strategy wins again, with a very similar outcome to the WAVES study, which used ECF-TAF and was blinded.

- In LATTE-2, an every 4 week schedule of cabotegravir and rilpivirine injections had fewer virologic failures than every 8 weeks at 48 weeks. One of the participants in the q8 week arm developed resistance to both rilpivirine and cabotegravir. Note that while both strategies were comparable to oral therapy, the q4 week approach will be used in the phase 3 studies based on these results. And in a funny mix-up showing how small the HIV research world is, the presenting author David Margolis was introduced as the other David Margolis. Bet the two John Bartletts have had a similar experience.

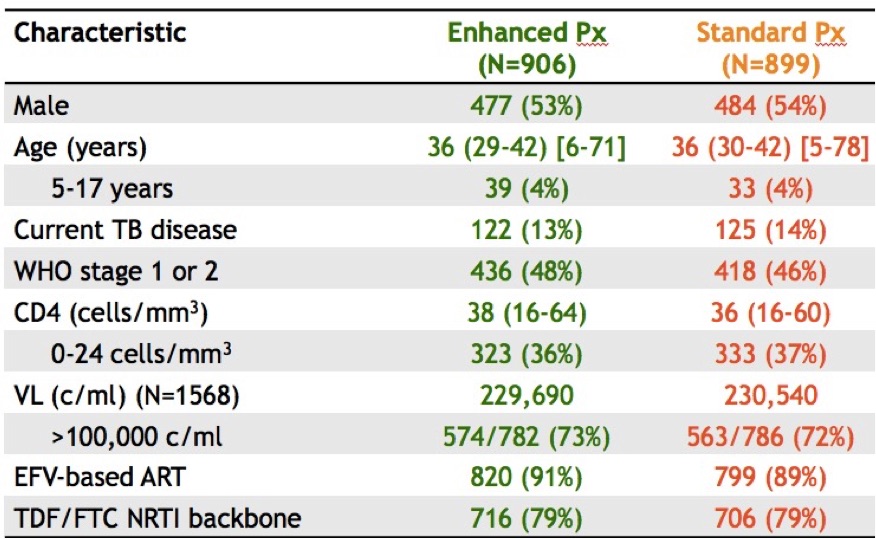

- In newly diagnosed patients with advanced HIV disease (CD4 < 100), adding raltegravir to standard ART did not improve clinical outcomes. Once again, 4 drug ART was not better than 3, though as expected HIV RNA declined faster and CD4 increased more in those receiving RAL. Called the REALITY study, this was an extraordinarily ambitious (sorry for the cliche, but it’s true) trial, conducted in multiple African countries and with 3 randomizations with a factorial design: intensive ART (this part), enhanced OI prophylaxis (see next bullet), and nutritional intervention (not presented here). This is the largest study done in advanced HIV disease, a group for whom we still have lots of questions since early mortality is so high.

- In this same vulnerable population with advanc

ed disease, enhanced OI prophylaxis improved survival. In addition to ART, the control arm received TMP/SMX (+/- INH depending on that local policy); the enhanced group received ART plus TMP/SMX, INH, fluconazole for 12 weeks, azithromycin for 5 days, and a dose of albendazole (why not). And take a look at those entry criteria! Mortality at 24 weeks: 8.9% vs 12.2% (p< 0.04), benefits sustained at week 48. These results could change treatment guidelines for this region; the number needed to treat/live saved was only 30. For the record, my friend/colleague Trip Gulick had a similar idea for a study of “pan-prophylaxis” in the USA — in 1991 (5 years before effective ART).

ed disease, enhanced OI prophylaxis improved survival. In addition to ART, the control arm received TMP/SMX (+/- INH depending on that local policy); the enhanced group received ART plus TMP/SMX, INH, fluconazole for 12 weeks, azithromycin for 5 days, and a dose of albendazole (why not). And take a look at those entry criteria! Mortality at 24 weeks: 8.9% vs 12.2% (p< 0.04), benefits sustained at week 48. These results could change treatment guidelines for this region; the number needed to treat/live saved was only 30. For the record, my friend/colleague Trip Gulick had a similar idea for a study of “pan-prophylaxis” in the USA — in 1991 (5 years before effective ART). - Updated 48-week results of the dolutegravir plus lamivudine (PADDLE) study had 1/20 with virologic failure. This is a single-arm pilot trial for patients with screening HIV RNA < 100k. Notably, the one with virologic failure had entry HIV RNA > 100K and was suppressed initially, but developed low-level viremia from week 36-48. No resistance was detected, and he re-suppressed on DTG-3TC and now is on triple therapy. (A second patient died from suicide before week 48 for an overall efficacy of 90%.) We need larger studies of this strategy in a broader patient population and with longer follow-up before it is widely adapted.

- A novel formulation of once-daily raltegravir was non-inferior to standard twice daily dosing. In this randomized, double-blind trial, the once daily arm was dosed as two 600 mg tablets daily, and all subjects received TDF/FTC. While overall outcomes were virtually identical (and excellent) in both arms, the once-daily arm had 5 cases (0.9%) of emergent resistance vs zero in twice daily arm. Interestingly, both arms had a lower rate of resistance than in prior randomized studies of raltegravir in naive patients.

- In START, the patients who benefited the most from early ART had HIV RNA > 50,000, or CD4:CD8 ratio < 0.5, or age > 50, or Framingham risk scores > 10%. These individual characteristics brought the number needed to treat for benefit of early ART (CD4 > 500) down from 128 to 40-50. Important fact for stat geeks — this was a univariate analysis.

- In the PROMISE Study, pregnant women with high nadir CD4s who continued ART post delivery had better clinical outcomes than those who stopped therapy. This was an important clinical question when this study was designed in the late 2000s, but the comparison had to be stopped early when the START study results became available last year. While the primary endpoint (AIDS, severe non-AIDS events, death) showed no difference between arms, those who continued had fewer other manifestations of HIV disease — TB, bacterial infections, zoster, mucosal candidiasis.

- Efavirenz again associated with suicidality in patients starting ART. This complex analysis (also from the START study) had to account for the fact that investigators avoided EFV-based regimens in participants with psychiatric disease (“channeling”), so in fact those receiving EFV had a lower rate of suicidality than those who did not. However, the rate was higher comparing EFV treated subjects to those in the deferred arm; this was not observed in other regimens. Given the results of the published ACTG study with similar findings, I would certainly avoid initial EFV-based therapy in those with a history of depression (and probably pretty much everyone if you have other options).

- In the ASTRAL-5 study, 12 weeks of velpatasvir/sofosbuvir for HIV/HCV co-infection cured 95% of study participants. This is a pan-genotypic regimen, a terrific new option for genotypes 2 and 3 in particular. Note that it cannot be given with efavirenz, and that if your patient is on TDF, a switch to TAF makes sense just as it does for ledipasvir.

- In the TURQUOISE-I, Part 2 Study, “PROD” (+/- RBV) cured 97% or more of those with HIV/HCV coinfection. (PROD = parataprevir, ritonavir, ombitasvir, dasabuvir.) Despite the relatively high pill burden and need for RBV in genotype 1a, this is a very effective regimen. Cumbersome study name, though. Couldn’t it have been “Turquoise 2”? Reminds me of this funny post on movie titles, probably could to the same thing for study names.

- Adjunctive therapy with vorinostat, maraviroc, and hydoxychloroquine did not decrease time to virologic rebound or reduce the size of the latent reservoir. This small randomized trial was conducted in patients treated during acute HIV infection — hence those most likely to benefit from cure interventions. A well done study, but probably one of many “negative” studies done in this area we’ll see over the next few years.

A few non-scientific words about being back in Durban after 16 years:

- Underrated beachfront. There’s plenty of activity during the day, with the surfers out between 6-7AM and the walkers, joggers, bikers, skateboarders, rollerbladers, and general observers appearing just a bit later to experience the beautiful sunrise. All day long a walk on the beachfront promenade was an ideal way to clear the brain of “conference head.”

- Great, affordable food. Not surprisingly, there is a pervasive Indian influence, as Durban has one of the largest Indian populations in the world outside of India. (If you get a bunny chow, be reassured it has nothing to do with rabbits.) And don’t skip the Pinotage and Chenin Blanc (I didn’t). Unfortunately, unlike my experience 2 years ago in Melbourne, the coffee is terrible.

- Pride. Every person I met from Durban was both extremely kind and extraordinarily proud of their city; all knew the history of the city well, and were eager to talk about it. I sensed a bit of both envy and disapproval of both Cape Town and Johannesburg.

- Uber rules. Cheap, reliable, and every bit (if not more) the “disruptive innovation” it is in the USA.

- Safety. It did seem as if the local advice about security was even stronger than the first time I visited. It was obvious stuff: don’t walk alone to the conference center, don’t carry your computer, don’t take out your cell phone on the street, and (repeatedly) never walk alone at night. Some of this, no doubt, is that the first time we were here it was pre-9/11. It’s a different world.

An ancillary benefit about going to this conference — the noise from a certain political convention was only a faint peep, or a footnote on a distant TV that happened to be turned to CNN!