An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 9th, 2017

What Should We Do About Persistent Low-level Viremia?

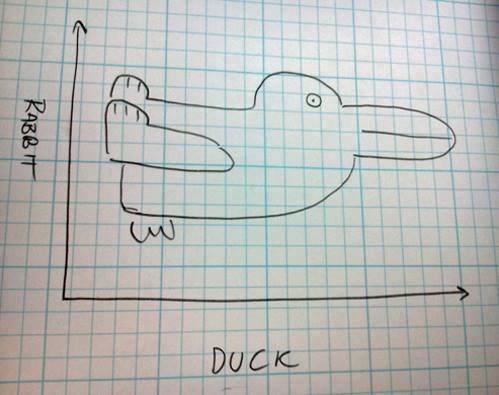

Thanks to our mail person for taking this portrait of our pets Louie and Otto. You can tell by their expressions that they miss us.

Here’s a most entertaining email about a tricky case (some details changed for the usual reasons), with my annotations in brackets:

Subject: Regimen intensification?

Hi Paul:

Long-time reader, first time caller. [Love that intentional mixed metaphor — should we start a radio talk show?]

We have a pt who was on TDF/FTC/EFV for a decade. He was undetectable the whole time. [He must have been difficult for his friends and family to find! Ha ha ha.]

He agreed to modernize, and another doc switched him to TDF/FTC/RPV, then TAF/FTC/RPV. He suddenly had a viral load that hovered just above the threshold of detectable — e.g. 59, 86, 101 — and it refused to go away. [Bad viral load!] So, we switched him to ABC/3TC/DTG. But he still has a persistent low viral load… like 95, 81, 72. [There is clearly no trend. Isn’t my statistical acumen impressive?] He says his adherence is virtually 100% and his partner confirms it. We were suspicious, but pharmacy also said he’s picking up his meds on time.

Interestingly, he admits he took TDF/FTC/EFV on weekdays only and stayed undetectable (grrrrr), so of course he wants to switch back! [Hey, that strategy probably works fine for that regimen.] He has no major mutations on a genotype run during the TDF/FTC/RPV phase, and no major mutations on an archive genotype either.

*{#%*$, Paul?! Do we switch him to a PI regimen, or just intensify by adding another agent. If so, which one? Do we check blood levels? Who does that? Or is he just not taking his meds every day, like before?

I know you’re a very busy man, Paul. [Nah. Just sitting here writing this blog post.] If you could take a moment to link me to any discussions, posts, or articles on this topic, I would be forever grateful.

With high hopes you can help! […which I am about to disappoint.]

Dorabella [I wanted to put her real name here, as she had aspirations to be detected on Google searches. But it’s a no-no for patient queries.]

Oh my, so much to unwrap here! Because when it comes to persistent low-level viremia in treated HIV patients, there’s much agony, gnashing of teeth, and confusion.

This is not the isolated low-level result preceded and followed by an undetectable one, the entertainingly termed “blip.” The blipologists of the world all agree blips mean essentially nothing (hence putting themselves out of business).

This patient’s situation is much tougher. So here, in a lazy bulleted list, are a bunch of things we know — and mostly don’t know — about this tricky situation of persistent low-level viremia.

- These patients have a higher HIV “reservoir.” If you look back, they often a history of advanced HIV disease, and/or very high pre-treatment HIV RNA.

- There are at least two types of low-level viremia patients. The first are those who are fully adherent to their meds, and their HIV RNA has been persistently detectable since we started using the more sensitive RT-PCR assays, especially compared to the bDNA, may it R.I.P. The second type are practicing “white coat adherence” — that is, not taking their medications very much, then remembering to do so again a few weeks before coming in for an appointment. A quick call to the pharmacy for a refill frequency check can sort this out.

- Some studies show low-level viremia is more likely to happen on boosted PI-containing regimens. The smart virologist Carlo Federico Perno from Italy has a nice theory why this is the case. It’s some combination of the mechanism of action of the PIs, where they act in viral replication, the defective virions, and the resistance barrier. So I wouldn’t switch to a boosted PI; this might make things worse.

- Several (but not all) studies suggest they are at greater relative risk of eventually developing true virologic failure, compared to those with undetectable HIV RNA. For example, in this study, a viral load between 50–200 was OK, but not 201–499. In this one, even 50-200 wasn’t benign — more failures. Regardless, the absolute risk is still quite low, especially if adherence is good. And they do not appear to be slowly developing resistance to their regimens.

- Intensification won’t work. Throwing more drugs at this low-level viremia on treatment doesn’t lower the viral load further. We know this from studies and from anecdotal clinical experience.

- They are not sick. Their CD4 cell counts remains stable, and they don’t get opportunistic infections. Data are mixed whether this low-level viremia is associated with higher levels of inflammation and immune activation markers, but you can’t do much about that even if it’s true.

- Hey, what about “undetectable = uninfectious”? Does this still count? Hmmm, tough one. We simply don’t know if they are more likely to transmit HIV to others compared to those with undetectable HIV RNA. Reassuringly, the viral load thresholds in the major HIV transmission studies were all higher than most patients with low-level viremia, including the one in this case. This query forced me to look it up, so here they are: Rakai (1500 cop/mL, untreated); 052 (400 cop/mL); PARTNERS (200 cop/mL); and Opposites Attract (200 cop/mL). (You’re welcome.) Isn’t that at least somewhat reassuring?

For the record, there’s a reason “Dorabella” didn’t just go to the HIV treatment guidelines for guidance, as there is ready acknowledgement that we just don’t know exactly what to do. Here are the blunt assessments from DHHS and IAS-USA, respectively:

“There is controversy regarding the clinical implications of persistent HIV RNA levels between the lower limit of detection and <200 copies/mL in patients on ART.”

and:

“Data are inconsistent about long-term effects of persistent HIV RNA between 50 and 200 copies/mL, and current data are insufficient to guide clinical management.”

Given this uncertainty, here’s what I wrote back:

Hi Dorabella,

Tough one! First, is it possible that you switched from the bDNA assay to the RT-PCR right around the time his regimen changed? That’s important, because if so, it would explain why he went from “undetectable” (<75 copies/mL) to low-level detectable — it’s not the regimen, it’s that the RT-PCR is more sensitive.

Second, we don’t really know what to do with these patients who have persistent low-level viremia. They have a higher viral reservoir, and some might eventually fail therapy (probably those with poor adherence), but intensification doesn’t seem to work. So keep him on a high resistance barrier regimen, like the one he’s on — or theoretically even better, switch to TAF/FTC, DTG.

Third, can I steal this case for the blog?

Thanks,

Paul

She obviously said yes to that last query!

October 1st, 2017

With Several Wrong Predictions Behind Me, Here’s One I Got Right

As I’ve mentioned before, I’ve been wrong on several predictions that ultimately came to pass.

Whoppingly wrong.

A partial list:

- Cameras in cellphones are a short-lived gimmick. My kids still tease me about that one.

- Buying clothing — and especially shoes — on the internet will never catch on. C’mon, you can’t try things on! How do you know if they fit?

- Avatar will be a huge bomb. Great special effects, but it cost over $200 million to make, has a silly story, and shallow characters. Who will pay to see that?

- A certain loud-mouthed businessman with a bad comb-over will never become President. Enough said.

However, when I wrote this summer that we might be at the end of HCV drug development, it turned out to be pretty spot-on.

Since then, two companies have ended their HCV drug development programs, one in early September, then another last week. You can read more about the business reasons here, but the simple medical reason is that it would be an enormous challenge to improve on what we have now — which is good news for our patients, provided remaining access issues can be resolved.

And by 2027, all of us will be traveling cross country on Segways.

You read it here first.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M3BeAu1pjIc]

(Stick around for the surprise ending in Coney Island.)

September 24th, 2017

Need a Positive Test for Something, Anything? We’ve Got You Covered!

(Inspired by various unvalidated, non-FDA approved lab tests.)

(Inspired by various unvalidated, non-FDA approved lab tests.)

Fatigued? Achey? Having difficulty concentrating?

Don’t have quite the “zip” you used to have when you were young?

If you suffer from any of these symptoms and are frustrated by unrevealing medical work-ups and negative blood tests, you’ve come to the right place.

For at DNA-Dx, we’ll find that positive test result — we guarantee it or your money back!

Using novel antibody tests with in-house interpretive criteria, home-brew PCR assays and in situ hybridization, imaginative culture techniques, and other proprietary amplification tests, we dial up the sensitivity of our testing so that no stray molecule of infection passes by us undetected.

Not sure what test to order? No problem! Just order our special Pathogen Discovery Panel ($1299.99), which rigorously evaluates blood, urine, and stool specimens for literally thousands of microorganisms, leaving no stone unturned.

It’s available now for a special introductory price of only $999.99. And once you get that positive test result — whatever it is — you’ll agree it’s worth every penny.

Not only that, but if you order now, you get a free canvas tote bag with the DNA-Dx logo. Great for picnics, trips to the beach, or just shopping.

About Us

DNA-Dx is a company founded by Dr. Melvin Smoot, a chiropractor with over 20 years experience in spine manipulation and core alignment. Based on his patients’ histories, he was convinced that many of them with negative work-ups for fatigue and aches were in fact suffering from an undiagnosed infection. Working with Scientific Director Virginia Gleeper, Ph.D. (an honors graduate of Eastern Slovenia Polytechnic Dietary Institute), Dr. Smoot opened his first lab in the food court of an abandoned shopping mall. By redeploying some leftover equipment (in particular from Sbarro and Panda Express), they were able to offer an increasingly broad range of diagnostic studies.

Today, the company has over 100 employees, with offices and labs in most communities with high median incomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q: What do you use for negative controls?

A: We at DNA-Dx do not believe in negative controls. Even our negatives are positive, provided you test them the right way. - Q: Can you refer me to any scientific validation of your results?

A: The best data supporting the validity of our tests are the numerous patient and client testimonials praising our work. We have literally thousands of letters, emails, and cashed checks that endorse what we do. - Q: What is your most common positive test?

A: Our expansive stool analysis routinely returns positive for hundreds of different microbes. - Q: What techniques do you use for testing for tick-related infections?

A: At DNA-Dx, we are very concerned about the rising incidence of tick-related infections. As a result, we feel it is our responsibility to do as many different tests as possible. We won’t stop until one is positive. - Q: One of my tests was positive — what do I do now?

A: If you click here, you can book a free consultation with one of our trained providers. They will guide you through our selection of a wide range of natural therapies and supplements, each proven* to help restore you to vigorous health. (Credit card required.) - Q: Do you take insurance?

A: No.

*Disclaimer: DNA-Dx is a registered trademark of DNA-Dx, Corp., and may not be reproduced, reprinted, or repurposed without the express written consent of DNA-Dx. Tests offered by DNA-Dx were developed and its performance characteristics determined by DNA-Dx. Tests and therapies have not been cleared or approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to diagnose or treat any condition.

Save

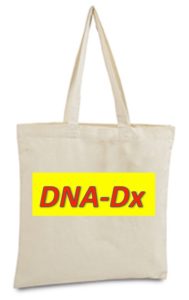

September 17th, 2017

Subunit Zoster Vaccine Soon to Be Approved — Should Patients Wait for It?

For the last year or so, conversations with patients about getting the zoster vaccine have gone something like this:

Patient: So should I get the shingles vaccine? I saw an ad for it on TV.

Me: Well, yes … and no.

Patient (confused — he/she has never heard me say anything but an enthusiastic “Yes!” to vaccines): What does that mean?

Me: There’s a better shingles vaccine coming soon, likely within a year. So I’d wait.

Now it looks like that wait is almost over.

This past week, an FDA advisory panel voted unanimously that the investigational subunit zoster vaccine is safe and effective for adults older than 50. The materials the panel reviewed are here.

FDA approval should follow soon — potentially next month — along with the critical review and recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The expert advisory panel based their decision on two pivotal randomized trials, ZOE-50 and ZOE-70, which compared the vaccine (administered as two doses) to placebo in people aged 50 and older or 70 and older, respectively. The studies enrolled nearly 30,000 subjects.

Vaccine efficacy was 97% in the first study, 89% in the second. The incidence of post-herpetic neuralgia was also reduced.

Importantly, adverse events were more common in vaccine recipients, but most were of mild severity. There was no significant difference in the incidence of severe side effects, deaths, or autoimmune processes.

Though these studies were not a direct comparison with the currently available live-attenuated zoster vaccine (Zostavax), remember that the efficacy of that vaccine is only around 50%.

Plus, it has been around long enough that we now know its efficacy wanes substantially over time.

That Zostavax is a live-virus vaccine creates additional difficulties. There is understandable concern — and confusion — about giving it to people with defects in cell-mediated immunity, for whom it’s contraindicated, and their household contacts, for whom it isn’t.

Finally, there are the practical difficulties of storing it before administration. Even clinics that do lots of immunizations — ours, for example — don’t have the required stand-alone freezer for storage of this vaccine. Many patients currently need to go to a pharmacy to get it, which adds an additional required step.

So this inactivated zoster vaccine won’t be just a “me-too” approval, but a real advance in prevention of what can be a truly debilitating condition. With the caveat that we lack safety data in very large patient populations — that should come after licensing — I’m not surprised the advisory panel voted the way they did.

It was exciting enough that I felt inspired to relay the following:

Big news because

1) Highly effective

2) Safe

3) Not live attenuated

5) Shingles can be BAD

5) Have been telling my pts about it for months! https://t.co/4HJrK0wNAo— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) September 13, 2017

Which just goes to show that I can’t count.

Save

September 4th, 2017

Meropenem-Vaborbactam, Zika Cases Decline, Gas Station Nachos, and More — An End-of-Summer ID Link-o-Rama

There’s so much interesting ID material out there.

The only solution — an ID Link-o-Rama, especially curated for the long Labor Day weekend.

(Actually, not really, but that sounded good.)

Off we go!

- Even if it doesn’t provide 100% protection, the flu vaccine may reduce the severity of influenza. Good to have this paper handy as clinics start to ramp up immunizations.

- Here are several sensible observations about Lyme Disease from a local physician. Not surprisingly, the first comments from readers are various forms of criticism. Sigh.

- The FDA approved meropenem-vaborbactam (Vabormere) for complicated urinary tract infections. Based on the clinical trials of this agent, however, its true indication should be treatment of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE). Take it from Brad Spellberg (who emphatically will not be in charge of marketing this drug):

FDA indication only relevant to control marketing. This is a CRE drug & that's what it should be used for. Any other use borders on criminal

— Brad Spellberg (@BradSpellberg) August 31, 2017

- One person died, 9 others were sickened by botulism from gas station nachos. As if we needed any other reason to avoid gas station nachos. Yuck.

- The incidence of Zika in endemic areas is dropping rapidly. But it’s not gone, and Zika’s permanent departure cannot be counted on. This is a nice quick summary of the mysterious coming and going of an epidemic, with the best explanation for its decline the effects of “herd immunity” — many got infected, never got sick, and are now protected from reinfection. As a result, they don’t pass Zika on to mosquitos or other people.

- With Zika incidence down, one company has pulled its plans to develop a vaccine. Difficult to test a vaccine’s efficacy when people are no longer acquiring the infection — how do you prove it’s working? And of course the market will be uncertain, to put it mildly.

- Blowing out birthday candles increases bacterial transfer to the cake by 1400%. The findings from this study represent either an unrecognized major health hazard or, conversely, a perfect example of why ID doctors are sometimes the deserved subject of ridicule. And in case you want another “germs are everywhere” study, which are irresistible click-bait, here’s more:

-

Microwaving your sponge increases the growth of potentially harmful bacteria. Not only that, it’s terrible for browning — to get good, crisp, golden-brown sponge skin, I suggest roasting or pan-searing.

- Ceftaroline may be an effective option for severe MRSA infections. This is a welcome review (disclosure, done by colleagues of mine), especially since there are no prospective studies of ceftaroline for this indication. A ceftaroline plus daptomycin vs vancomycin comparative study for MRSA bacteremia would be optimal — though doubt it will ever happen.

- Does switching to a dolutegravir-based regimen cause weight gain? This is the second published paper implying such an effect (the first is here). Hard to come up with a plausible mechanism. Still, weight gain from HIV therapy in general remains a knotty unsolved problem.

- In candidemia from a urinary source, early drainage improves outcome. A reminder that the vast majority of these cases relate to obstruction of some sort that needs remediation (surgical, percutaneous, or endoscopic).

- A researcher contracted HIV in a laboratory despite no known breach of infection control. Exactly how this happened remains unclear, but the phylogenetic analysis of the virus supports this was a lab-based isolate. Transmission of HIV in the lab or hospital setting is (fortunately) so rare that any such event deserves special scrutiny.

- Compared to 1990, global deaths due to communicable diseases are down substantially. The only condition showing an increase is HIV/AIDS — and if we looked at death rates since the expansion of ART in the early 2000s, these are down too.

- Taking responsibility for treating opiate addiction is a natural fit for some ID doctors. It’s not easy, and requires additional training, but among the various medical subspecialists, who better than ID? This follow-up piece in the Boston Globe makes the excellent point that, like treating HIV, our field is taking on a highly stigmatized illness (opiate use disorder) — one with numerous infectious complications.

- Martin Shkreli, the guy responsible for increasing the price of pyrimethamine 5000%, isn’t well liked. I know, shocking. Still, reading this transcript from his recent jury selection is quite something. Imagine if this were your legacy.

- Maybe doxycycline doesn’t cause dental staining in children after all. It’s a small study (n=38), but the results are reassuring — especially in a highly Lyme- and anaplasma-endemic region like this one!

- Clofazimine has a growing role in treating non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Unfortunately, obtaining clofazimine for each patient who needs it is the very definition of burdensome. Time to change this difficult access problem!

- Gunshot-related spinal cord injuries and infected pressure ulcers — a highly complex, dangerous, and expensive combination. In this perspective, the authors state that people with this condition experience “slow but irreversible and expensive death sentences,” sadly all too true. They call for a multidisciplinary approach, meaning investing resources upfront to avoid complications and costly hospitalizations.

And now, a non-ID section, some medically related, some not:

- “Admit to observation” can saddle a patient with enormous uncovered hospital or rehabilitation facility charges. This is an excellent example of the strange incentives in our healthcare “system”. Check out the reader comments to get a sense of how difficult it can be when someone “admitted” to the hospital actually isn’t considered admitted at all.

- Is our national obsession with football fading? Longtime columnist George Will and I don’t always see things the same way, but with this piece he’s hit a real home run (metaphor chosen intentionally). The opening sentence alone will bring smiles to English majors and football haters across America.

- So long, Walter Becker, co-founder of Steely Dan! The band’s jazz-influenced rock and slick studio sound have always polarized my friends, eliciting rapturous praise, active dislike, or complete indifference. Count me as part of the cheering section.

- In a recent game, Joey Votto of the Cincinnati Reds went 0 for 0 with 5 walks. Joey Votto is the best baseball player you’ve never heard of. In case you’re wondering what makes him so good, the most important skill a hitter can have is getting on base. So 0 for 0 with 5 walks is a very good game indeed — it’s just a quirk of baseball scoring that it’s not called 5 for 5.

- Most of the dietary advice we got growing up was wrong. That’s the inevitable conclusion of this large cohort study, which found that high carb, low fat diets were associated with a higher risk of death, while total fat intake was related to lower mortality. Doesn’t it always come back to Michael Pollan’s brilliantly simple formulation? Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.

- If you want to know what makes wine fanatics tick, “Cork Dork” is an interesting, funny, and entertaining read. Terrific title, too. Warning — ordering wine at a restaurant will never be the same!

For Steely Dan fans out there, a personal favorite, this relatively obscure track:

August 27th, 2017

Who’s Most Likely to Leave an Out-of-Office Message While on Service?

Once upon a time, I used being on service as a convenient excuse for not writing very much — or certainly, not writing very much of importance — on this site.

Once upon a time, I used being on service as a convenient excuse for not writing very much — or certainly, not writing very much of importance — on this site.

The on-service time also allowed me to poke gentle fun at my colleagues, several of whom always turn on an “out-of-office” message when they attend on the inpatient ID consultation service.

I’m talking about this thing that responds instantly when you email them:

I am currently attending on the inpatient consult service. During this busy time, I may not be able to respond to email in a timely fashion. If you need to reach me urgently, please page me by calling xxx-xxx-xxxx, or leave a non-urgent message here and I will respond shortly.

Thank you,

Rudolph

Reminding me of this post, my friend Carlos Del Rio sent me this email earlier this year:

Going on service April 1st. Should I put my “Rudolph” message up?

I’d advised Carlos to check Emory’s Policies and Procedures — am sure it’s in there somewhere.

Now, having just completed a couple of weeks doing inpatient ID consults — and falling behind on emails — I thought it time to add a few additional observations about this practice:

- Who is most likely to do it? Let’s call people who do this “OOODS.” (Pronounced like the first syllable of “noodle,” and standing for “out-of-office during service” types.) My anecdotal impression is that OOODS are predominantly academic physicians, people who know patient care is important but don’t do it on a day-to-day basis. Hence they want to “clear the decks” of other pressing responsibilities. A minority might be full-time outpatient clinicians who only rarely do inpatient work.

- When not on service, they are generally very responsive to email. OOODS are often “inbox zero” types who wouldn’t think of allowing the sun to set on a critical research or administrative query. So when busy consult days happen, and the long hours on the wards make it impossible for them to keep up, they want to reassure their colleagues and friends that they haven’t suddenly decided to abandon academic medicine for more frivolous activities. Imagine the speculation!

“Hey, I emailed Dr. Smith 12 hours ago, and he hasn’t gotten back to me yet — that’s weird, he’s usually so quick to respond. Plus, no out-office-message.”

“Yes, that’s weird. But he’s a pretty big Phish Phan — maybe seeing all their summer concerts?”

- They’re generally pretty important. Many exceptions to this rule, but the academic rank and productivity of OOODS is impressive. One study found that the number of citations for papers published by OOODS was significantly higher than non-OOODS, even when controlling for total RVUs generated on the consult service. NIH grant dollars and the impact factor of their published papers were also significantly higher. If you don’t believe me, the published paper can be found here.

- One person who inspired the original post identified herself almost immediately. Shortly after I wrote it, I received this email:

Hey, I’m Rudolph aren’t I??? Is that a bad thing?

First, let the record show that this OOODS person who emailed me was only one of several people who sent me a similar query, as I adapted the sample out-of-office message from a bunch of different ones used by friends and colleagues.

Second, it is by no means a bad thing — it’s just a thing some people choose to do; others don’t (I don’t) — as evidenced by the fact that this particular OOODS person was most deservedly just appointed an extremely important leadership position.

Congratulations, Rochelle!

August 20th, 2017

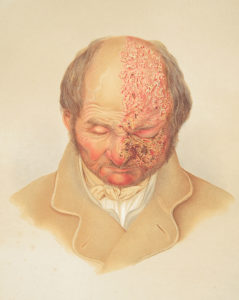

Two Quick Thoughts Inspired by Inpatient ID Consults, and An Inspirational Baseball Poster

A couple of quick thoughts for those of us doing inpatient care these days:

Thought One: Is daptomycin now preferred over vancomycin in most clinical settings?

It’s taken a while, but we’re getting there — close to that Gladwelllian “tipping point”. Allow this recap of vancomycin’s problems:

- The growing recognition that higher drug levels — the levels we want — bring with them more side effects.

- The extraordinary hassle and imprecision of monitoring vancomycin levels.

- The enormous variability in dosing due to differences in clearance from patient-to-patient.

- The lengthy vancomycin infusion time (at least 60 minutes/dose) which, if you have a patient on every 8 hour dosing, means they are spending many of their waking hours receiving vancomycin.

If you add to these issues the substantial decrease in daptomycin’s cost since it went generic, it’s hard to justify using vancomycin over daptomycin for many non-pneumonia indications these days.

Daptomycin is far from perfect, but if it replaces vancomycin there will be few tears shed on its behalf — vancomycin isn’t such a great drug either. Beta lactams are preferred over both of them for susceptible organisms.

And for the next time there’s a lull in the conversation with your friends, here are some fun facts about daptomycin, including how it was discovered on Mount Ararat in Turkey.

Thought Two: Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) should be avoided whenever possible.

Two recent studies highlight the hazards associated with sending patients out of the hospital with intravenous lines to complete antibiotic therapy:

- Out of 339 patients prospectively studied from two academic medical centers, 18% experienced a significant adverse drug event, most commonly during the first two weeks after discharge. Note that most retrospective analyses have even higher rates, probably because many are discharged without being in an organized OPAT program.

- In people who inject drugs — a particularly challenging patient population who increasingly have “indications” for OPAT — a whopping 61% failed their OPAT course.

Aside from the medical challenges of OPAT, there’s also the clinical service side — which is dismal. Since payers typically do not reimburse providers for monitoring OPAT, this gives us ID doctors two terrible choices — provide the service for free because it’s good for patients or, alternatively, refuse to do it and document (leverage) the suboptimal care to get institutional funding.

The former is an example of our being “too nice”; the latter just makes me uncomfortable, but is increasingly required.

Bottom line: we should strive to give oral over IV antibiotics at discharge for all patients, except when the data strongly support parenteral therapy. Oral treatment is safer, cheaper, and usually just as effective.

Finally, given the current political climate, isn’t this poster just awesome?

It’s a subway poster from 1950, published by the Institute for American Democracy.

And as a baseball-crazy ID doctor, of course I love it!

Save

August 13th, 2017

Dog-Related Infectious Diseases as an Excuse to Show Pictures of Dogs

For proof that we’re not like other human members of the planet, when ID doctors think of dogs, it sometimes brings to mind one or more of following associations:

- Gastroenteritis due to Campylobacter jejuni. No, there’s nothing cuter in the world than a puppy — but remember that these little critters are particularly predisposed to symptomatic (and asymptomatic) campylobacter infection, and, given our inability to resist picking up puppies and cuddling them, not surprisingly can be the source of human infection as well. Older dogs are less susceptible, so probably best to keep the puppies out of the elder care facilities.

- The wonderfully named bacterium Capnocytophaga canimorsus. This is a rare cause of sepsis after dog bites — in particular in people without spleens, those who consume too much alcohol, and the immunocompromised. A good trivia question for parties is to ask someone the bug’s original name, which was “DF-2”, standing for “Dysgonic fermenter.” Then ask them what “dysgonic” means. Then ask the difference between “DF-2” and “DF-1”. That will make you the life of the party. (For the record, I have no idea what “DF-1” is.)

Dogs are the “definitive host” of Echinococcus granulosus. This parasitic infection (which can cause nasty cystic lesions in the liver, lungs, and brain) is most common in people who raise sheep, which like humans act as intermediate hosts. But dogs are required to complete the life cycle, and they get infected when they eat discarded meat and internal organs from echinococcus-infected sheep. That might be yuck to us, but it’s no doubt yum to them. Here’s the CDC-approved life cycle diagram, if you don’t believe me.

Dogs are the “definitive host” of Echinococcus granulosus. This parasitic infection (which can cause nasty cystic lesions in the liver, lungs, and brain) is most common in people who raise sheep, which like humans act as intermediate hosts. But dogs are required to complete the life cycle, and they get infected when they eat discarded meat and internal organs from echinococcus-infected sheep. That might be yuck to us, but it’s no doubt yum to them. Here’s the CDC-approved life cycle diagram, if you don’t believe me.- Rabies. (Cue scary music here.) Even though there hasn’t been a human case of rabies linked to a dog bite sustained within the USA in decades, every ID doctor frequently receives calls about dog bites and the risk of rabies. That’s not surprising since 1) dog bites still account for over 90% of human cases world-wide; 2) rabies is nearly 100% fatal, and; 3) there are anti-vaccine crackpots who have spread their nonsense to their dogs. Couldn’t make this stuff up.

Of course that’s hardly the full list — there’s Dipylidium caninum (dog tapeworm), Ancylostoma caninum (dog hookworm), Microsporum canis (ringworm), Brucella canis (transmitted to humans when infected pregnant dogs have spontaneous abortions), and Ehrlichia canis (the cause of ehrlichiosis), just to list those that have the Latin root for dog in their name.

And we could on with several other infections that, in various settings, have been linked to dogs. A true potpourri of zoonoses! There’s giardiasis, Yersinia pestis (yes, that’s the plague), leptospirosis, Pasteurella multocida (though cats really deserve most of the blame for this one) — even MRSA!

Which brings me to the real reason for this post, which is to show three pictures of dogs that struck me as particularly fetching, infectious risks of owning these beasts notwithstanding. First, my friends just got an adorable puppy named Elijah — and here he is.

Second, and just so someone close to me won’t get jealous, here’s a recent picture of a very vigilant Louie, who has clearly spotted some danger in the distance (or maybe just a squirrel).

Third, I happen to work with Francisco Marty, who is not only a remarkable clinician and clinical researcher, but also one extraordinary photographer. And below is proof, entitled “DUMBO’s Dachshund!”

Woof!

August 6th, 2017

Have We Reached the End of HCV Drug Development?

Two new HCV regimens gained FDA approval recently, bringing us closer to the end of this extraordinary phase of drug development.

Think about it — has there ever been a more spectacularly rapid improvement in treatment of anything? If so, please let me know what that is. Remember, as recently as early 2013, highly toxic interferon-based therapy (with ribavirin and telaprevir or boceprevir) was still standard-of-care.

The recent approvals: Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir (Vosevi) on July 18, indicated for patients who have failed prior treatment with either sofosbuvir or an NS5A inhibitor. Twelve weeks of treatment (one pill daily) will cure 95–96% of patients, and pretreatment presence of NS5A, NS3, or NS5B resistance mutations does not reduce response. A month of sof-vel-vox — which will only be used as a salvage therapy — is priced at $24,900.

Then, glecaprevir-pibrentasvir (Mavyret) was approved on August 3rd. A pan-genotypic regimen that includes both an HCV protease inhibitor and an NS5A inhibitor, “G/P” is 3 pills daily, requiring only 8 weeks of therapy in treatment-naive individuals without cirrhosis. Clinical trial results show cure rates in the high 90s, with a low incidence of treatment-related adverse events requiring drug cessation.

Glecaprevir-pibrentasvir can also be used in patients with renal  impairment (including dialysis), prior treatment failure of genotype 1 with either an NS5A inhibitor or PI (but not both), and in compensated cirrhosis. Treatment duration should be increased to 12 weeks in those with prior treatment or cirrhosis.

impairment (including dialysis), prior treatment failure of genotype 1 with either an NS5A inhibitor or PI (but not both), and in compensated cirrhosis. Treatment duration should be increased to 12 weeks in those with prior treatment or cirrhosis.

So where does that leave us in terms of “unmet needs” in HCV therapy?

Let’s review what we currently have:

- Nearly 100% of those who get treated are cured.

- Most regimens are one pill daily.

- Ribavirin is rarely required for treatment-naive patients.

- Side effects leading to drug discontinuation are exceedingly uncommon.

- Treatment duration is only 8–12 weeks.

- Drug interactions are mostly manageable; if not, HCV treatment is so short that temporary discontinuation of the conflicting drug is usually fine.

- Several pan-genotypic options are available.

- Certain therapies are also effective for treatment-experienced patients with resistance.

- Some regimens are safe and effective for those with moderate-severe renal disease — even hemodialysis.

From a medical perspective, this doesn’t leave out a whole lot, does it? Treatment of HCV is so easy there’s a strong push in some circles to move it to front-line providers in primary care — and of course outcomes in their hands are as good as with hepatologists and ID specialists.

Yes, cost of and access to HCV therapy remains an issue, especially in certain regions.

But things have vastly improved in this area too. With prices way down from the crazy days of early 2014 (when the non-FDA approved “sim-sof” regimen was > $100,000/cure), we should anticipate that more payers will stop medically unjustified policies such as fibrosis criteria, negative toxicology screens, and limiting prescribing of HCV therapy to specialists.

And market forces are doing something — note that the wholesale price of G/P is $13,200 per month, very close to the negotiated discounted price for LDV/SOF with the VA and certain state Medicaid programs.

Which brings me back to the title of this post — Have We Reached the End of HCV Drug Development?

If we’re not there yet, we’re certainly close.

Here’s a poll about where we should go with HCV research — please vote!

Save

July 30th, 2017

Really Rapid Review — Paris IAS 2017

Last week, the International AIDS Society meeting returned to Paris for the first time since 2003.

Last week, the International AIDS Society meeting returned to Paris for the first time since 2003.

Yes, you and I are that old. Jeeze.

Here’s a Really Rapid Review® of some of the conference highlights, roughly ordered by “cure”, prevention, treatment, and complications.

As always, feel free to use the comments section for notable studies I might have missed — thank you!

- A child remains “in remission”, with an undetectable viral load for over 8 years after stopping treatment. This case — similar the “Mississippi baby” but with no relapse — has no detectable HIV RNA in blood, small amounts of detectable HIV DNA, no replication competent virus, and none of the HIV immune responses typically seen in HIV controllers. Treatment course was 40 weeks around two months after birth as part of a clinical trial. One of my colleagues says it’s the closest thing to a “cure” since Timothy Ray Brown, though for obvious reasons it’s always risky to use that word.

- What happens when HIV is treated extremely early after HIV acquisition? A man on PrEP was diagnosed with an HIV RNA of 220, 4th generation Ag/Ab negative, around 10 days after acquiring HIV. He was treated for 34 months with combination ART, which led to numerous negative reservoir assays, then stopped treatment — only to experience virologic rebound (same as original infecting virus) 225 days later. In summary, reservoir and viral diversity were reduced — but virus not eradicated.

- More evidence that undetectable on treatment means a person won’t transmit HIV. There were zero HIV transmissions in 343 serodiscordant MSM couples followed an average of 1.5 years — which included an estimated 12,000 acts of condomless anal intercourse.

- “On demand” pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) worked in the IPERGAY study even in those with less frequent sex. The regimen was 2 pills of TDF/FTC before sex, then one each of the next two days (4 total). Strategy was protective even in those taking 15 or fewer pills/month.

- Cabotegravir with every 8 week dosing looks good for PrEP. Pharmacokinetics somewhat different in men vs women, but these results demonstrate levels likely to be protective with every 8 week dosing after a 4-week loading dose. Phase 3 comparative study vs. TDF/FTC ongoing.

- Weekly MK-8591 effective in animal model of PrEP. The drug, a “nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor” with a mechanism of action somewhat different from current NRTIs, is highly potent with a long half life. Study used rhesus macaques and SIV; none became infected after SIV challenge that infected untreated controls.

- New HIV diagnoses in MSM have declined slightly in the USA since 2008. The reduction is steepest among men aged 34-44 and in whites, while rates are increasing in younger men (13-34), and in Hispanics, younger blacks.

- Bictegravir/FTC/TAF non-inferior to dolutegravir/ABC/3TC in treatment-naive patients. 92.4% vs 93.0% < 50 at week 48. Significantly less nausea in BIC/FTC/TAF arm, but both regimens very well tolerated. No difference in bone outcomes. No resistance in either treatment arm.

- BIC/FTC/TAF non-inferior to DTG + FTC/TAF in treatment-naive patients. 89.4% vs 92.9% < 50 at week 48. Again, no emergent resistance in any of the few study subjects with treatment failure. This BIC/FTC/TAF regimen is under review by the FDA; if approved, it could be available early next year. (Disclosure: I was the presenting investigator.)

- Doravirine/TDF/3TC non-inferior to EFV/TDF/FTC. 84% vs 81% < 50 at week 48. DOR with significantly fewer CNS side effects, better lipids. 1.6% of DOR vs 3.3% of EFV subjects with resistance. Results of this and prior phase 3 DOR study suggest this NNRTI has the best efficacy, safety, and tolerability profile in this drug class.

- Single-arm study (n=120) of DTG + 3TC demonstrated 90% success (HIV RNA < 50) at week 24. Good news, it seemed to work well even in the 25% with baseline HIV RNA > 100K. Less good news, one study subject (in the < 100K group) developed 3TC and possibly integrase resistance (a K263K/R mixture). Contrast this with zero resistance in any of the triple-therapy studies of DTG. Phase 3 comparative studies of DTG + 3TC ongoing.

- 3TC was non-inferior to TDF/3TC when given with fixed-dose DRV/r. With the caveat that this is an interim analysis of a fully powered study, and used a 400 copy/mL threshold, the results are encouraging — and DRV/r + 3TC is a much more attractive regimen than the LPV/r + 3TC regimen used in GARDEL. Note the use of a non-FDA approved DRV/r coformulation (study done in Argentina). In the USA, this would presumably be DRV/c, can we extrapolate?

- Switching to a single-pill coformulation of DRV/c/FTC/TAF was non-inferior to continuing a boosted PI. If approved, this would be the first boosted PI single-tablet regimen. A treatment-naive study (compared to DRV/c, TDF/FTC) is also ongoing.

- With 2 NRTIs, DTG superior to LPV/r as 2nd-line therapy after failure of a 2-NRTI/NNRTI-based regimen. The results so favored the DTG strategy that the study’s Independent Data Monitoring Committee stopped the LPV/r arm (all subjects are now receiving DTG). Findings should have a huge impact on clinical practice — will DTG (not boosted PI) based regimens now be the standard of care for second-line therapy? Can we extrapolate to those currently virologically suppressed on boosted PIs + NRTIs due to NRTI resistance?

- In patients with advanced HIV disease, adding maraviroc to standard ART did not improve clinical outcome. This was a very well done trial, negative results notwithstanding. More studies in this challenging patient population needed!

- DTG + TDF/FTC is as safe as TDF/FTC/EFV in pregnancy. Reassuring analysis of nearly 845 DTG-treated and 4593 EFV-treated pregnancies in Botswana, as infant outcomes were similar. A randomized study of TAF/FTC + DTG in pregnancy is ongoing.

- Raltegravir also appears safe in pregnancy. Pending results of ongoing studies, raltegravir plus TDF/FTC is our current go-to regimen in pregnancy — where it is much better tolerated than boosted PIs.

- Every 4 week or every 8 week injectable cabotegravir plus rilpivirine maintains virologic suppression. No additional cases of virologic rebound occurred between weeks 48-96 (there was one in the q8 week arm initially). The every 8 week strategy was nearly superior to oral therapy. Fully powered phase 3 studies of CAB/RPV given q 4 weeks are ongoing.

- A single dose of MK-8591 suppresses HIV RNA for at least a week. A dose as low as 0.5 mg achieved this effect, demonstrating extraordinary potency. One patient (according to the presenter) had prolonged suppression even after stopping therapy (he/she was supposed to go on standard ART).

- In patients at high CV risk, a switch from boosted PIs to DTG maintains virologic suppression, improves CV risk profile. Eligible subjects had no prior treatment failures. Lipid benefits were particularly beneficial with the DTG switch, similar to what was seen in SPIRAL and SWITCHMRK, both of which involved switching from boosted PIs to raltegravir.

- Zoledronic acid improves bone mineral density more than switching off TDF. Of course in patients with low bone density, clinicians should probably employ both strategies given the increasing availability of TAF.

- Telomere length is worsened by smoking (especially) and viremia. I cite this study since this molecular observation so strongly correlates with anecdotal clinical experience — so many of the patients I follow with “accelerated aging” have an extensive smoking or viremia history. Or worse, both.

- Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir highly effective in HIV/HCV co-infected patients. Strategies tested were 8 weeks for no cirrhosis (n=137), 12 weeks for cirrhosis (n=14), with 150/151 cured. This “G/P” pan-genotypic regimen is likely to be FDA-approved soon, and can be used with any integrase or RPV-based HIV regimen.

- Large (n = 721) randomized clinical trial of cryptococcal meningitis in Africa finds 1 week of amphotericin + 5FC is the best strategy. Note that fluconazole + 5FC (an all-oral regimen) was nearly as good, underscoring the need to make 5FC more readily available in resource-limited settings, as amphotericin treatment is not always feasible.

- Use of adjunctive corticosteroids in PCP does not adversely influence subsequent CD4 recovery. I’ve always wondered about this! Now we know.

Now for a few non-scientific observations:

-

The weather was mostly, cool, cloudy, and intermittently wet. Regardless, Paris is among the most beautiful and lively cities in the world. (Not such an original opinion, I know.)

- A bike race visited Paris at the same time. Lots of excitement.

- What a weird conference center. Numerous escalators, winding hallways, and a disorienting layout made getting around tricky. At least the session halls for the slide sessions were very comfortable (though some over-crowded).

- Why can’t we have a subway system like that? The Paris Metro seems to get better all the time — fast, clean, reliable, inexpensive. I’m sure it’s not perfect, but is there a better urban rapid transit system in a large city anywhere else?

- Although per capita cigarette consumption is roughly the same in France and the USA, it sure doesn’t seem that way. I’ll anecdotally say that lots of professionals (even doctors, gasp) and other well-to-do people smoke in France — you don’t see that much in the USA anymore.

- Next year’s conference is in Amsterdam. July 23-27.

Speaking of bicycling around Paris …

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8ErsO92Bfw]

Save