An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

December 16th, 2017

CDC Receives List of Additional Forbidden Words and Phrases

Right on the heels of prohibiting certain words or phrases in the Centers for Disease Control’s budget documents, the President’s Office of Financial Services has issued a second list.

Right on the heels of prohibiting certain words or phrases in the Centers for Disease Control’s budget documents, the President’s Office of Financial Services has issued a second list.

Now, not only must CDC officials avoid using words such as “vulnerable”, “diversity”, “fetus”, “transgender”, and “evidence-based”, they also have to steer clear of several other words or phrases.

These include the following, which were issued along with the stated rationale and, at times, proposals for alternate or cautionary language:

- “Scientific studies” — Please replace with “Dr. Oz says …”

- “Data” — Delete — it is too difficult for us to know whether this word should be singular or plural.

- “Susceptible” — We propose the following wording — “at risk due to weakness in character or upbringing or both.”

- “Funding” — We prefer the term, “market forces”.

- “Autochthonous transmission” — When cited, please include a note that it may cause blindness and/or hairy palms.

- “Transparent” — Replace with “allows light to pass through so objects can be distinctly seen.”

Certain other words — including “balanced”, “cautionary”, “inclusive”, “thoughtful”, “measured”, and “kumquat” — are also on the forbidden list, without any explanation.

CDC officials have yet to respond to these requests publically, but several have noted off the record that this is the first time they have received comments from the President’s office hand-written in crayon.

Disclaimer: In case kumquat jokes aren’t your thing, this is satire.

December 10th, 2017

Injection Drug Use-Related HIV Cases Increase in Massachusetts — Is This the Start of a Trend?

Recently the Massachusetts Department of Public Health sent out this concerning notice:

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) has noted an increase in newly diagnosed and acute HIV infections among persons who inject drugs (PWID). To date in calendar year 2017 (through November 21), there have been 64 HIV infections reported among individuals who inject drugs in Massachusetts … Over the past 5-10 years, newly diagnosed HIV infection in PWID amounted to 32-62 cases annually, representing a stable proportion of 4-8% of all reported HIV infections. Investigation of cases is ongoing.

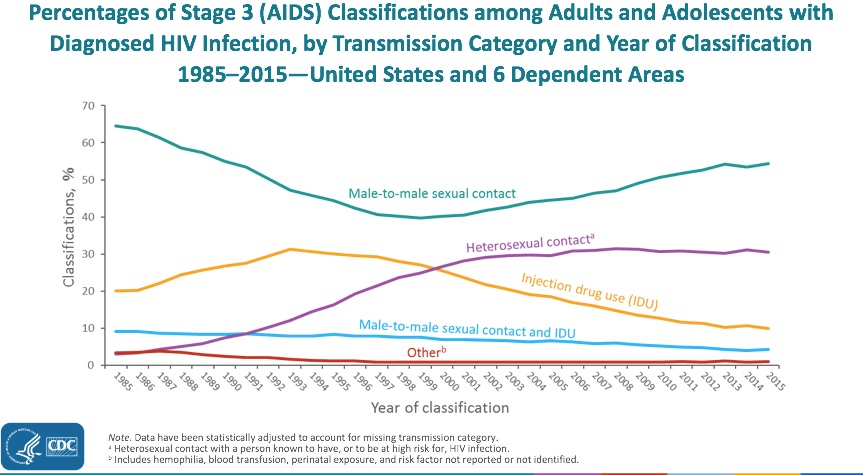

Undoubtedly, one reason for the notice is that it stands in stark contrast to a long-term trend. Indeed, the drop in injection drug use-related HIV has been one of the unheralded success stories in the USA HIV epidemic.

Once a very prominent “transmission category,” it has declined more than any other risk factor, now accounting for less than 10% of new HIV diagnoses per year. For a broader view, here are AIDS cases in the USA since the beginning of the epidemic, showing the steady decline in cases attributable to injection drug use since the mid-1990s:

This decrease in cases is even more remarkable when viewed in the context of our national opioid epidemic, a problem we ID doctors are reminded of on a daily basis — not from HIV, but from serious invasive bacterial infections and, to a lesser extent, hepatitis C.

By contrast, new cases of HIV due to injection drug use alone are now relatively uncommon in the United States. A notable recent exception was the 2015 Indiana HIV outbreak, where nearly 200 new HIV infections occurred in four months in a rural community hard-hit by opioid addiction.

A skillful CDC investigation found that just one person with HIV was the source of the outbreak, which was then fueled by a needle-sharing network. The outbreak demonstrated the potential rapid spread of HIV in this population — and then the ability of syringe exchange programs to control it.

Are we seeing the beginning of something like the Indiana outbreak now in Massachusetts? Or is this year’s increase — admittedly rather small to date — just a temporary blip?

Regardless, good work by the MDPH in getting the word out — vastly preferable to be early rather than late to recognize this trend.

I’ve heard anecdotally there might be other HIV outbreaks nationally among people who inject drugs. What’s been your experience where you practice?

December 3rd, 2017

Why, Even with Depressing Predictions About Flu Vaccine Effectiveness, We Should Still Recommend and Get It

Image from “Ferrets : their management in health and disease with remarks on their legal status”, 1897.

Each year, the print and broadcast media round up a bunch of experts on influenza and ask them to predict the severity of the upcoming flu season.

Most of the time their responses are noncommittal — predicting how bad the flu season will be year to year is tricky business, akin to picking stocks, making 12-month weather forecasts in an almanac, or naming the winner of the World Series during spring training.

But this year is different. A particularly bad flu season in Australia, mostly due to H3N2 influenza A, has public health officials concerned we’re going to see the same thing here in the Northern Hemisphere.

And our flu vaccine’s estimated effectiveness against the H3N2 strain?

This low effectiveness isn’t due to a strain-vaccine mismatch. The problem appears to be related to alterations in key flu vaccine proteins during egg-based vaccine production. Or, if you prefer a more technical explanation, here’s a quote from an excellent perspective on challenges in the flu vaccine published last week in the NEJM:

Antigenic characterization using ferret reference antiserums indicates that egg-propagated vaccine viruses acquired changes in the hemagglutinin that subsequently altered antigenicity against circulating strains.

(You have to love that sentence.)

Regardless of the mechanism, even by the meager standards we hold the flu vaccine, this 10% number is a disappointment.

But this low efficacy notwithstanding, you might note that the CDC, public health officials, and the vast majority of ID doctors still strongly recommend the vaccine. They/We do so for several reasons:

- The Australia experience with H3N2 may not be recapitulated here. Although H3N2 is widespread in the USA early in the flu season, circulating flu strains change even within an individual year. In this terrific summary, read how even flu experts grapple with the vagaries and unpredictability of seasonal flu activity. And that person next to you in the subway with the cough and drippy nose may have influenza B, against which our vaccine provides much better protection.

- Even partial protection is better than none. A recent paper found that the flu vaccine prevented influenza-related hospitalizations, suggesting attenuation of severe illness. It adds to existing data supporting that the vaccine provides benefit even when it doesn’t completely prevent the illness.

- If you’re a healthcare provider, you owe it to your patients. This is especially the case if your patient population includes babies, or pregnant women, or the elderly, or people with cardiopulmonary disease, or individuals struggling with obesity, or immunocompromised hosts. Good chance this covers 100% of clinicians!

- It’s the only thing we’ve got. At least on the vaccine front, this is sad but true. There are various common-sense activities we can educate our patients about, but the adherence to these practices won’t be high.

- It’s safe. The vaccine does not cause the flu. Furthermore, the vaccine does not cause the flu. Finally, the vaccine does not cause the flu. Got it?

We doctors, nurses, PAs, and pharmacists can be forgiven if the the weak efficacy data might take some of the energy out of our annual recommendation. But let’s try to keep giving the vaccine.

And hey, you smart vaccine researchers working on that “universal” flu vaccine — we’re rooting for you!

So is the ferret.

November 26th, 2017

Should Medical Students Bring Laptops to Lectures?

You can file this under, “Old man yells at cloud,” but here goes.

You can file this under, “Old man yells at cloud,” but here goes.

Twice a year now for over a decade, I’ve been lecturing the senior medical students in a therapeutics and pharmacology course. It’s an elective, but it’s very popular — most of the class takes it.

Not surprisingly, my topic is Treatment of HIV (duh) and my goal is to convey the “big picture” themes of HIV treatment and prevention — who gets treated and when, what we choose and why, the basics of pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis, the remaining challenges.

Since most of the students will never become ID or HIV specialists, I don’t go into much minutiae — no molecular diagrams of mechanisms of action, or complex resistance patterns, or immunology flow charts, or phylogenetic trees.

As a result, I stopped using Powerpoint years ago in this talk, instead making it as interactive as possible. I put a few key principles up on a white board as take-home points, and use cases to illustrate each one.

There’s only one problem — a few of the students never look up from their laptops, and hence don’t join in the process.

And nearly all of them now have laptops; the laptop-to-student ratio is very close to 1. It’s much greater than 1 if you count the other screens periodically appearing in the room (phones, tablets, etc).

It might be my teaching style that’s boring these laptop lovers, of course, or the topic (you could imagine that treatment of HIV isn’t high on the list of must-know items for future orthopedists), or some combination.

But there is evidence that laptops in classes and lecture halls impair learning. In this piece just published in the New York Times, the author cites several such studies:

A growing body of evidence shows that over all, college students learn less when they use computers or tablets during lectures. They also tend to earn worse grades. The research is unequivocal: Laptops distract from learning, both for users and for those around them.

It’s not just that some are checking emails, messaging friends, or engaging in whatever social media is currently vogue among their demographic. Their laptop activity is also making it harder for others in the class to concentrate, according to some studies.

Finally, the note-taking process itself is less effective at storing new material when it’s typed rather than written.

So “No laptops” is a “No brainer”, right?

Wait — it’s not quite so simple.

I’m one of those terrible-handwriting sorts for whom learning to type opened up a whole new way of communicating. I type much faster than I write, and my handwritten notes are often illegible. During our weekly case-conference, I type the details of the case into my laptop because I could never write fast enough longhand to get the details down.

I’m also the first to admit that the internet is the most extraordinary resource. If I mention the START study (which I inevitably do), the students can find the original reference instantaneously.

Plus, there’s the paternalism issue cited in the Times piece, which even more strongly applies to medical students:

Most college students are legal adults who can serve in the armed forces, vote and own property. Why shouldn’t they decide themselves whether to use a laptop?

Bottom line is that I think there are pros and cons to using laptops in the classroom — which means it’s perfect fodder for a poll.

November 19th, 2017

Some ID/HIV Items to Be Grateful For, 2017 Edition

It’s late November — the days are shorter and colder, and the trees have abandoned their bold plan to keep their leaves this winter.

It’s late November — the days are shorter and colder, and the trees have abandoned their bold plan to keep their leaves this winter.

We can forgive them their optimism — it was a historically warm October.

This time of year also brings us Thanksgiving, easily my pick for the best national holiday. Family, friends, food, a short work week, and no presents to buy — provided you’re not a turkey, what’s not to like?

Time for a list of ID/HIV things to be grateful for, an annual tradition:

- A better vaccine for herpes zoster has been FDA approved, and will be available soon. I’ve already covered the new “adjuvanted subunit” shingles vaccine in some detail here, but some of the advantages deserve repeating: it’s much more effective, it’s not a live virus vaccine so can be given to immunocompromised hosts, and it will be much easier to store and dispense. On the minus side is that two shots will be required; in addition, it will have more side effects than the current zoster vaccine (we won’t have a full understanding its safety profile until it’s in clinical practice). Nonetheless, one could envision a dramatic drop in this sometimes debilitating condition if the vaccine is widely adopted. Has a clever name, too.

- “Undetectable=Untransmittable” is now unequivocally endorsed by the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control. Support on this issue from these important research and public health agencies is critical to getting the word out — people with HIV on suppressive antiretroviral therapy cannot sexually transmit the virus to others. Here’s a terrific FAQ, and a concise editorial, both summarizing the data behind “U=U”. (H/T to Carlos Del Rio for this one.)

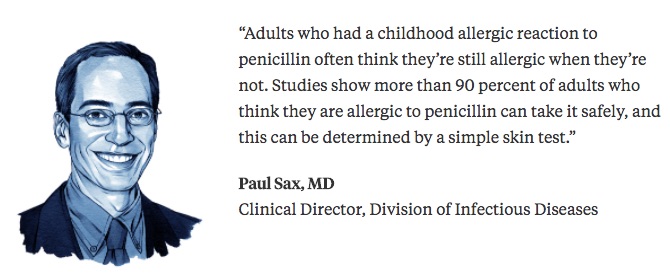

- Most people with an “allergy” to penicillin aren’t really allergic, and proving that they can take penicillin safely is easy and improves their care. Our hospital’s magazine did a special issue on immunology research, and asked me “What common lack of knowledge about the immune system would you like to correct?” Rather than mention some arcane fact about innate vs. adaptive immunity (about which I would just have been faking it), see my response below:

Once “penicillin allergy” is off the problem list, all kinds of clinical benefits occur, including receipt of fewer unnecessary broad spectrum antibiotics and lower costs. Send your patients with “penicillin allergy” for skin testing now!

Once “penicillin allergy” is off the problem list, all kinds of clinical benefits occur, including receipt of fewer unnecessary broad spectrum antibiotics and lower costs. Send your patients with “penicillin allergy” for skin testing now! - The Immunization Action Coalition’s excellent web site, in particular their “Ask The Experts” section, continues to be an invaluable resource. We ID doctors get a lot of questions about vaccines from other clinicians, and this remains my go-to site for answers — it’s clear, concise, authoritative, and well-referenced. Plus, it’s a point of pride in our house to stay current on vaccine recommendations, where my wife the pediatrician is no slouch on this topic. Got to keep up!

- Resistance to integrase inhibitors remains extremely rare. Despite this widespread use of this drug class, resistance is remarkably, wonderfully uncommon. The likely explanation is that the “INSTIs” are so potent and well-tolerated that patients on integrase-based regimens are either virologically suppressed (and hence don’t get resistance), or have very poor adherence (and hence don’t get resistance). Given the high resistance barrier of dolutegravir (and soon bictegravir), this fortunate situation should continue. Regardless, it will be critical to monitor the prevalence of integrase resistance globally as dolutegravir-based regimens increasingly become the default treatments in settings that don’t routinely use viral load monitoring.

- Staph aureus is becoming more sensitive to antibiotics. MRSA rates are down, penicillin-sensitive strains are up, and the bug rarely figures out how to develop resistance to either TMP-SMX or doxycycline. The big worries over vancomycin, daptomycin and linezolid resistance also never really materialized, and ceftaroline susceptibility also remains stable. For the record, I mentioned Staph last year, but I’m repeating now for two reasons: First, there isn’t a more important pathogen for inpatient Infectious Diseases than Staph aureus (first-year ID fellows undoubtedly would agree); and second, it’s a surprising counter to the grim news about untreatable gonorrhea, the spread of highly resistant acinetobacter, and the ever increasing rate of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. No one knows why this is happening with staph, but hooray anyway! Let’s hope this trend continues.

That should do it for this year. What are you grateful for this Thanksgiving week?

And in the “harvest” theme …

November 12th, 2017

Poll: Adventures in Buffet Dining — Is It Time to Get Rid of Those Food Tongs?

My friend Joel Gallant wrote this provocative post on his heavily trafficked Facebook page:

While standing in line at the cafeteria today, it occurred to me that it was once acceptable to use your fingers to pick up a bagel, a piece of bread, or a cookie from a tray, but this is now viewed as an antisocial act. Everything requires a serving utensil, including tongs for hand-held food. I’m no germophobe, but it occurred to me, while trying to wrestle a very large bagel off a tray using a very small pair of tongs, that this new etiquette is a big step backwards in terms of hygiene and infection control.

Imagine a cafeteria line during cold season. Someone in front of you has a viral infection. Perhaps he blew or wiped his nose before getting in line, or sneezed into his hands instead of his sleeves. Which would would you prefer: that he grab a cookie between his thumb and index finger, with the risk that he MIGHT touch an adjacent cookie in the process, or that he pick up a pair of plastic tongs with his snot-laden hands, the same pair of tongs that will be handled by everyone who follows him in line?

I’m lucky for two reasons — first, Joel gave me permission to bring this important issue to you readers of this site, whose interests skew towards matters of infections in general, and likely for some of you, food safety.

Second, he’s such a clear writer that he’s articulated the debate perfectly. Do these ubiquitous serving tongs actually prevent infections? Or do they facilitate their spread?

To clarify, this controversy is only about the use of tongs for dry food items — bagels, cookies, a slice of bread, a muffin. No one is suggesting we start using our hands to serve ourselves sliced cucumbers in the salad bar, or lasagna and beef bourguignon in the cafeteria line.

That would just be messy, infectious risks aside.

A quick search on the matter quickly yields this study, which not surprisingly shows that E. coli can be passed back and forth between hands and salad tongs.

And if it’s viruses you’re worried about, this study showed plenty of norovirus and adenovirus on “environmental surfaces” at “food service operations” — but did not specifically mention tongs.

For the record, Joel expressed his personal conflict of interest on the matter:

For the record, Joel expressed his personal conflict of interest on the matter:

Disclaimer: I’m not impartial; I’m a klutz with tongs.

He also sent me this photo of tongs being used for foil-wrapped food, which he views as an example of tong-mania taken to an absurd extreme. Practically a “Tong [sic] Dynasty”, if you’ll pardon the terrible pun.

I guess he’s obsessed.

So what do you think?

November 5th, 2017

More Fun With Old Medical Images!

Sometimes we clinicians, researchers, teachers, and medical administrators need a break from our grueling work schedules and responsibilities.

With that in mind, I offer a second installment of Fun With Old Medical Images! — which I’ve cleverly entitled, More Fun With Old Medical Images!

With an up-front thanks to the National Library of Medicine — who are truly putting our taxpayer dollars to good work — let’s get started.

Here’s Numero Uno:

Before her annual Thanksgiving swim in the Atlantic, Kristin always donned her confusing protective wetsuit.

Confusing is right! If you want to be even more befuddled, here’s what the owner’s manual says:

The health guide: aiming at a higher science of life and the life-forces, giving nature’s simple and beautiful laws of cure, the science of magnetic manipulation, bathing, electricity, food, sleep, exercise, marriage, and the treatment for one hundred diseases: thus, constituting a home doctor far superior to drugs.

Never mind the manual, let’s go swimming! But don’t you think long sleeves would be warmer? Brrrr.

Speaking of bare arms, on we go to #2:

White coats may spread germs! So do neckties and jacket sleeves! Arrghhh, bugs are everywhere!

The only solution — wear nothing, as this handsome fellow is doing.

And no, I have no idea whether he’s wearing trousers.

Here’s #3 for consideration:

The doctor always trusted Herbert, his Diagnosis Monkey, to review patient charts when planning his day at the office.

Confession: I’m not sure what a “Diagnosis Monkey” is either.

But if monkeys can type Shakespeare, maybe they can make medical diagnoses too. And imagine if you had one! What fun!

Can Herbert also work with modern EMRs? What about EHRs? What’s the difference anyway?

And not only is Herbert a crack diagnostician, he’s also great at selecting ICD-10 codes. Today’s best: W61.62XD: Struck by duck, subsequent encounter.

Which reminds me — make sure you always schedule a follow-up after a duck assault. That initial encounter never quite captures the whole essence of the duck-striking.

Here’s #4:

Form, function, fashion, and fun — Ray-Ban’s latest styles are sure to entice beachgoers everywhere.

Get it? They’re sunglasses! Imagine how popular you’ll be at the pool wearing these sleek specs.

It was tempting to go topical with a solar eclipse reference on this one, but the next eclipse won’t occur in the USA until April 8, 2024.

And if there’s one thing we stress on this highly educational NEJM Journal Watch site, it’s clinical relevance. We want to be useful.

Finally — and aren’t you sad we’re nearly done? — here’s #5:

As if we needed additional proof of the health benefits of coffee, there’s a profound transformation for you.

And I suggest that Janet choose her profile photo for OKCupid after that morning cup of Joe.

That’s all this time, folks. We’ll be back next episode with more highly valuable medical knowledge.

Meanwhile, can’t the police do anything about this scofflaw?

October 29th, 2017

Cellulitis, Lyme, VZV, MRSA, TB, Tdap: Great Questions from ID in Primary Care

We’ve just finished our annual course Infectious Diseases in Primary Care, and once again our attendees — all busy clinicians — asked some excellent questions.

Below, a small sample:

- What is the drug of choice for cellulitis in outpatients who are allergic to penicillin? Importantly, this is about cellulitis — not abscesses — which means most are caused by beta strep (group A, B, C, G). If you can find a history of safe use of a cephalosporin, go with that. (Many of us ID doctors prefer cefadroxil to cephalexin, since the former is twice-daily.) If cephalosporins aren’t an option, one commonly cited alternative is clindamycin, though there’s increasing resistance to the latter among certain strep in the community, especially group B. Some would say that TMP/SMX is an option, but I’m not a fan. Levofloxacin is active versus most beta strep, so this also should be considered, even though it never appears in guidelines. The price of linezolid has come down since it went generic, but it’s still expensive, and not always well tolerated. But whatever you choose, remember that more than 95% of people with penicillin allergy aren’t actually allergic — have them get a skin test, and remove that penicillin allergy from their chart! So gratifying to do that.

- How long does the Lyme serology stay positive after treatment? Although Lyme serologies gradually decline in most patients, they can in individual patients persist for years, making follow-up serologies as a “test of cure” a particularly confusing practice — so let’s stop doing it! Importantly, this applies to both IgM and IgG antibody responses, which makes IgM antibodies an unreliable marker of recent infection unless they are correlated with recent-onset symptoms and exposure. Because there are no predictors of who will and will not have persistent Lyme antibodies, most of the time the diagnosis of reinfection relies heavily on clinical presentation. I hope someone out there is working on a reliable PCR or antigen test for Lyme — we really need it!

- One of my patients received the chicken pox vaccine, and now wants to get pregnant. Her varicella serology is negative. Should I revaccinate? Unfortunately, the varicella titers commonly used in clinical practice only reliably check for natural immunity, not vaccine-induced immunity. As a result, they are not recommended as a marker of varicella vaccine efficacy. But the bottom line is that if you have a clear record she received her vaccine, there is no need to revaccinate your patient — or check titers.

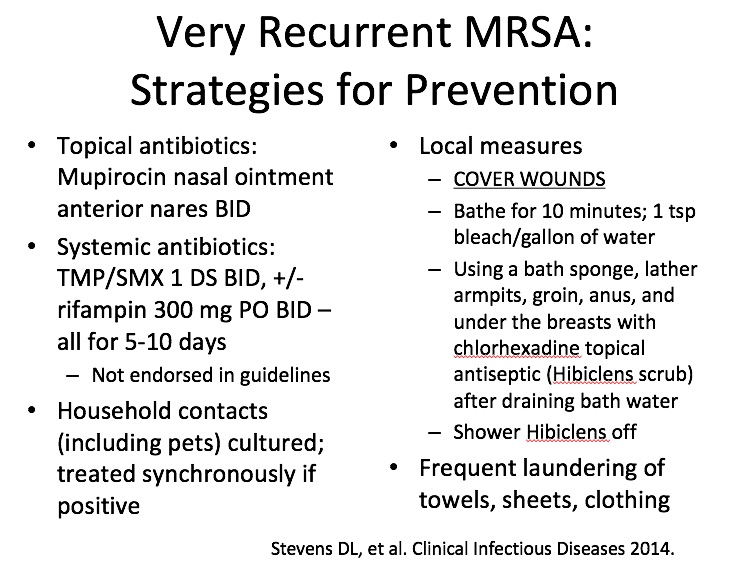

How do you manage recurrent MRSA? Once these poor suffering people find their way to ID doctors, they’ve usually had multiple episodes occurring over months, sometimes even years. So these recommendations aren’t for the people with a few minor boils, or a couple of recurrences. Assuming that underlying conditions such as hidradenitis suppurativa are excluded, we go for the “try everything” approach, summarized at right. To enforce the effort, we pass out this information sheet. An important caveat is that clinical trials haven’t confirmed the efficacy of these strategies, and hence guidelines do not formally endorse them. Good luck!

How do you manage recurrent MRSA? Once these poor suffering people find their way to ID doctors, they’ve usually had multiple episodes occurring over months, sometimes even years. So these recommendations aren’t for the people with a few minor boils, or a couple of recurrences. Assuming that underlying conditions such as hidradenitis suppurativa are excluded, we go for the “try everything” approach, summarized at right. To enforce the effort, we pass out this information sheet. An important caveat is that clinical trials haven’t confirmed the efficacy of these strategies, and hence guidelines do not formally endorse them. Good luck!- If recurrent zoster is so rare, why is the zoster vaccine recommended for people who have had shingles? It’s true that in immunocompetent hosts, recurrent zoster is rare — you can read more about recurrent zoster (both the real thing and fake-outs) in this post. However, a small fraction of people who get shingles remain at risk for another episode, presumably because the first outbreak did not sufficiently boost their antibody responses, or because their immune system is not intact. Furthermore, as anyone who does clinical practice knows, the motivation for zoster immunization is particularly high for people who have experienced a case themselves! While the full details of the ACIP recommendations for the just-approved zoster subunit vaccine are not yet available, presumably they will also recommend this vaccine for patients with a history of zoster, just as they did for the live virus zoster vaccine. Notably, 92 patients with a history of prior physician-diagnosed zoster received the subunit vaccine in a prospective study, with the primary endpoint being antibody responses; encouragingly, 90% of those immunized had a four-fold increase in their VZV titers.

In TB screening, do you have a preference for using either an IGRA or a skin test? In general, the IGRA (interferon gamma release assay) is better — less operator dependent, no second visit required, no false positives from BCG. While the IGRA is more expensive, its advantages over tuberculin skin testing were acknowledged in the latest guidelines, which stated that the IGRA is generally preferred when available. See the summary table at right (click on image to see it larger).

In TB screening, do you have a preference for using either an IGRA or a skin test? In general, the IGRA (interferon gamma release assay) is better — less operator dependent, no second visit required, no false positives from BCG. While the IGRA is more expensive, its advantages over tuberculin skin testing were acknowledged in the latest guidelines, which stated that the IGRA is generally preferred when available. See the summary table at right (click on image to see it larger).- I take care of a nurse who got Tdap last year, and was recently exposed to pertussis. Should she get preventive antibiotics? It would be great if we knew the degree of pertussis protection afforded by the Tdap vaccine after a direct exposure, but unfortunately those data are limited; in addition, secondary cases of pertussis have occurred within households even when immunizations are up to date. As such, it’s recommended that most healthcare workers receive antibiotic prophylaxis after exposure to a case, as they may come in close contact with people at high risk of severe illness from pertussis.

- You ID doctors seem pretty smart. Where do you get all this information? Don’t be fooled by our apparent omniscience; it’s an illusion we create to compensate for the fact that we don’t do invasive procedures. Mostly, we just know where to look stuff up.

- What’s made you laugh out loud recently? How about this recent CDC report?

Q: Waiter, what's this bat doing in my salad?

A: Sleeping?https://t.co/RK8aJLFLwK via @CDCgov— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 27, 2017

I know, I know — we have a peculiar sense of humor in this field of ours.

October 22nd, 2017

Price’s “Quarantine” Comment a Startling Example of Remaining HIV Stigma and Ignorance

In case you missed it, Betty Price, a Georgia state representative, said the following last week:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFTGZyVnzo0]

If you head over to the Youtube page with the above video, and read the comments (yes, I know, wading in such waters can give one a dim view of humankind), you’ll see she’s hardly alone in holding this view. The stigma, fear, and ignorance associated with HIV are still very strong; those of us who do this work on a daily basis might forget this sad fact.

And I suspect Price was well aware that she’d have some supporters before she made this public statement. It’s all the more remarkable that she said these things as a physician (she was an anesthesiologist before entering politics), but then again her husband Dr. Tom Price didn’t exactly distinguish himself when the topic of vaccines came up during his brief tenure as secretary of Health and Human Services.

So what should we, as infectious diseases/HIV specialists, say about this regressive and anachronistic perspective?

How about taking the high road and sticking to the science?

- There are multiple proven ways to prevent HIV transmission. Condoms, pre-exposure prophylaxis, and treating people with HIV all work really, really well — and new infections are substantially down in the USA because of them. Do you think that Rep. Price knows that everyone who takes HIV treatment becomes uninfectious to others?

Quarantines for infectious diseases should be reserved for conditions that are an immediate threat to the public health. It’s an extreme measure, one that is both expensive and logistically difficult, so mandating a quarantine should not be undertaken lightly. The CDC graphic on the right depicts diseases for which isolation and quarantine may be warranted. The most recent important example was Ebola (a viral hemorrhagic fever), which is highly contagious, especially during the acute illness, and potentially lethal. Back in 2002, it was SARS. HIV infection, with its long clinical latency period, lack of transmissibility except during sexual or blood contact, and effective therapy does not fit into this category.

Quarantines for infectious diseases should be reserved for conditions that are an immediate threat to the public health. It’s an extreme measure, one that is both expensive and logistically difficult, so mandating a quarantine should not be undertaken lightly. The CDC graphic on the right depicts diseases for which isolation and quarantine may be warranted. The most recent important example was Ebola (a viral hemorrhagic fever), which is highly contagious, especially during the acute illness, and potentially lethal. Back in 2002, it was SARS. HIV infection, with its long clinical latency period, lack of transmissibility except during sexual or blood contact, and effective therapy does not fit into this category.- There are no data that an HIV quarantine would even work, or be even feasible. Before undertaking such a costly program — costly not only in dollars, but also in the enormous loss of personal freedom — shouldn’t we at least have some evidence that it would reduce HIV incidence? And what criteria would she propose for the quarantine? All 1.1 million people with HIV living in the USA? Only those not on treatment? Or only those not on treatment who are sexually active or sharing needles with others? How would she prove these claims? (Amazing what web cams can do these days, but still.) Would the program provide food, treatment, and housing? If so, where would these sites be, and how would they be funded? (I guess there might be some money that’s no longer being used for private jets,)

To be fair, Price has backed off of her original statement, saying she meant it “to light a fire under all of us with responsibility in the public health arena.”

She certainly drew attention to the dire situation in Georgia, where the ongoing HIV epidemic is considerably worse than in most other states — it has the second highest rate of new cases, after Louisiana. The primary driver is Georgia’s large, underserved, and mostly minority population that cannot access regular care.

It’s people there — and everywhere — who are not on treatment and both get sick and sustain the epidemic, a lose-lose situation.

Grady Memorial Hospital is the famous Atlanta safety-net institution affiliated with Emory. In an account of his experience as an ID fellow at Grady, Dr. Jonathan Colasanti wrote the following:

After finishing 2 weeks on the general ID consult service, I was astonished as I prepared my patient log for submission to the Program Director. One-third of our 62 consults were patients infected with HIV … All of the patients were black. Excluding a patient with acute infection, the mean CD4 T-cell count was 64 cells/µL and over half the patients had <50 cells/µL. The mean viral load was 4.2 log copies/mL … Half of the patients were admitted with OIs or AIDS-defining illnesses, whereas many of the others suffered from processes directly related to living with a suboptimal immune system.

Until we have an HIV vaccine, the solution to stopping the HIV epidemic is to get people tested, on treatment, and keep them in care — regardless of race or ability to pay.

We know that. Do our elected officials?

October 15th, 2017

The Best Antiretroviral Therapy for Pregnant Women? The Controversy Continues

There’s considerable controversy in an area of HIV medicine that one would think should be all but solved by now.

It’s what HIV treatment we should give pregnant women.

The issue isn’t how to prevent the virus from being transmitted to the newborn — suppress the virus in mom, baby doesn’t get it — it’s what’s safest for the pregnancy outcome.

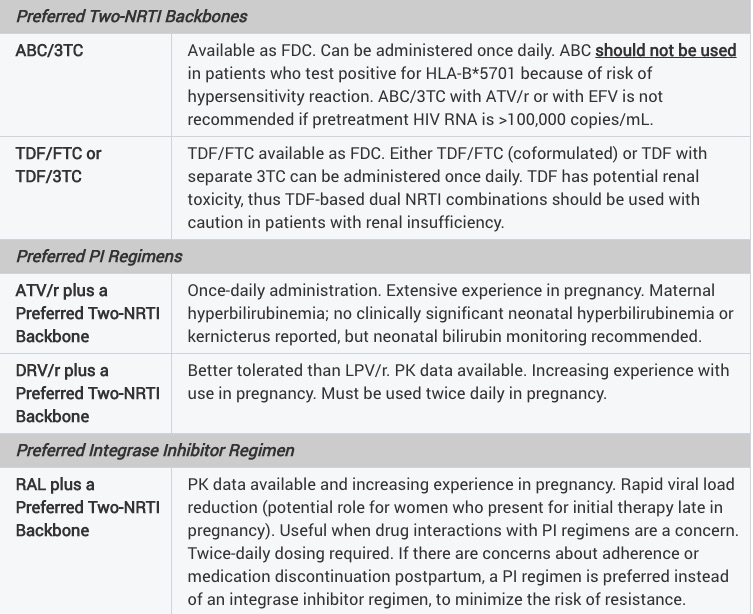

The uncertainty spills over to the HIV perinatal guidelines, which are notable for how different they are from those for non-pregnant adults:

Taken literally, these guidelines would support a regimen of ABC/3TC and twice-daily DRV/r for a pregnant woman — something we’d never prescribe a non pregnant treatment-naive patient for several obvious reasons.

Additionally, there is only one integrase inhibitor-based regimen — TDF/FTC, raltegravir — while INSTI-based regimens dominate the general recommendations for HIV treatment. There just aren’t enough data yet on the use dolutegravir in pregnancy, though we did see some encouraging information during the IAS meeting this summer. And information on tenofovir alafenamide are scant.

Now, potentially making HIV treatment during pregnancy even more divergent from standard-of-care, non-pregnancy treatment, comes a surprising new set of recommendations from the British Medical Journal.

Entitled Antiretroviral therapy in pregnant women living with HIV: a clinical practice guideline, the paper recommends using zidovudine/lamivudine over tenofovir DF/emtricitabine during pregnancy:

Here’s their stated reason for this surprising recommendation:

Tenofovir and emtricitabine probably increase the risk of early neonatal death and preterm delivery <34 weeks compared with zidovudine and lamivudine; this is more certain when they are combined with lopinavir/ritonavir.

Importantly, most of the data they cite in support of this recommendation come from the PROMISE study, which did show higher rates of very preterm delivery before 34 weeks and early infant death with TDF/FTC compared with ZDV (a.k.a. AZT)/3TC. But an important caveat is that the drugs were given with LPV/r at high dose, a regimen we rarely use today, and which substantially increases tenofovir levels.

The authors of the PROMISE study themselves responded to the BMJ piece, stating that they do not agree with the recommendation to use ZDV/3TC over TDF/FTC for several reasons. While I encourage people interested in this topic to read their full comment, they cite important observational data on the use of TDF/FTC/EFV:

Compared with a regimen of TDF-emtricitabine (FTC)-EFV, all other regimens, including AZT-based ART, were associated with higher risk of adverse outcome; increased risk of preterm birth, very preterm birth and neonatal death were observed for infants exposed to AZT-lamivudine (3TC)-lopinavir-ritonavir.

Plus, we can add to these reassuring data a new paper, just published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases. In a prospective evaluation of 422 pregnancies, the researchers found that TDF was not associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, and that preterm birth occurred less frequently among pregnancies exposed to TDF.

My take? We know from thirty years (yep, it’s been that long) of experience that ZDV has considerable toxicity — subjective side effects such as nausea and headache, and additional problems related to mitochondrial toxicity, including bone marrow suppression, lipoatrophy, and lactic acidosis.

As a result, it’s very hard to imagine prescribing zidovudine again under any circumstances, including during pregnancy. Today, the most commonly used initial regimen at our hospital during pregnancy is TDF/FTC and raltegravir; if patients are on a successful treatment and become pregnant, we generally continue that, almost regardless of what it is.

And we eagerly await the results of a three-arm study in pregnant women, led by my colleague Shahin Lockman, which is just getting started. It compares TAF/FTC plus dolutegravir, TDF/FTC plus dolutegravir, and TDF/FTC/EFV.

This, we hope, will move treatment of pregnant women with HIV closer to the treatment we offer non-pregnant adults.