An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 12th, 2025

The Patient Did Well — So the Insurance Company Won’t Pay

Sometimes, you can predict a bad outcome. Examples:

Sometimes, you can predict a bad outcome. Examples:

- Proposing marriage after an awkward first date — and doing so over gas station nachos.

- Moving to a Cambridge apartment with no off-street parking, then buying a Tesla Cybertruck.

- Trying to recruit for ID fellowships from a group of cosmetic dermatologists.

But predicting what happens in clinical medicine? Not so easy. Which is why the clairvoyance expected by certain health insurance companies baffles the mind — they seem to believe we can diagnose, prognosticate, and determine outcomes with the omniscience of the Oracle of Delphi.

Take this recent gem. I’m sharing it here not because it’s unusual, but because the absurdity deserves a moment in the spotlight.

(Part of a series.)

Here’s the scenario (some details changed to protect privacy):

The patient, a 64-year-old man, went to our emergency room with fatigue, acute kidney injury, and a hemoglobin drop. He’d recently undergone gastric sleeve surgery, making the clinical status more uncertain than usual — plus a background of diabetes and high blood pressure as medical comorbidities. Given the symptoms and risk factors, he was admitted to medicine for hydration, monitoring, and endoscopy. He got better. We all celebrated. Cue the credits.

But then… the sequel. (Spoiler alert: It’s a horror film.)

A few days later, I received an email saying that the insurance company had denied inpatient level of care — in plain English, they didn’t want to pay. Would I have time to do a “peer-to-peer” discussion to try and reverse the decision?

They might as well have asked me to call an airline to rebook a cancelled flight during a massive Nor’easter, that’s how much I was looking forward to this task. But given how justified the admission was, and my trying to be a team player to defend good clinical practice in the face of our Private Insurance Overlords, I set up some time to talk with my “peer.”

I use quotation marks because while I’m sure she was, technically, a healthcare professional, her role in this drama felt more like prosecutor than peer.

She had some of the hospital data. Not all. Enough to cherry-pick to support their refusal to pay, but not enough to understand the full context of the case since, of course, she had never seen, spoken with, or evaluated the patient.

She asked me a series of questions, some of which were about information she already possessed, as if hoping I’d contradict myself like a suspect in a police procedural. (“So you’re saying the patient had a drop in his hemoglobin during the hospitalization? Interesting, doctor… very interesting. I see here it remained 7.5–8.3 during his stay. Do you consider that a drop?”)

I explained, again, the patient’s presentation. The drop in hemoglobin from his baseline of 10.5. The post-bariatric surgery. The concerning acute kidney injury in someone with diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. You know — the reasons why he was admitted.

But then came the decision, delivered with the cool finality of a game show host eliminating a contestant. Because the patient had no hemodynamic instability during his stay, and no ongoing bleeding, the hospitalization was deemed… unnecessary.

Denied.

“I cannot overturn the decision,” she said, as if quoting some higher order of evidence from randomized clinical trials rather than a faceless algorithmic edict she no doubt had up on her screen as she was talking with me.

I took a deep breath.

Then I asked her to imagine herself as the patient — sitting in the ER, post-recent surgery, with those symptoms and those lab results. Or better yet, as the clinician doing the initial assessment, deciding whether to admit or to send him home.

Would she have discharged this man? Would her judgment have changed if she weren’t now on the payroll of Giant Healthcare Insurance Company? Had she, like so many burned-out clinicians, left clinical medicine because of pointless, time-wasting demands like this conversation — only to end up perpetuating the same dysfunction from the other side?

No answer. Silence on the other end. Then, she repeated, “Thank you, Dr. Sax for your perspective. I cannot overturn the decision.”

Because of course, the outcome — the good outcome — was only apparent after the fact. One reason to admit people is when we don’t know if they’ll do well.

So yes, the patient got better. No, he was not critically ill. But that’s not evidence the admission was unnecessary; that’s evidence the admission went about as well as could be hoped. Isn’t that what we all want?

Unfortunately, our healthcare system now seems to reward retrospective omniscience more than clinical judgment. “If only you had known he wouldn’t bleed again!” they say. Right. And if only I had known to buy Nvidia stock when it first went public in 1999.

I’ll stop now — time to call my airline because my flight has been canceled due to an unexpected mid-summer blizzard. Should be more fun than this call.

July 7th, 2025

Two Pandemics, Compared: Reflections on HIV and COVID-19

“Dr. Sax, what’s it like to have lived through two pandemics as an ID doctor?”

“Dr. Sax, what’s it like to have lived through two pandemics as an ID doctor?”

The question came from a brand-new intern during afternoon sign-out. I took a breath — because wow, were they different.

HIV: It Felt Like A Calling, One Miraculously Rewarded

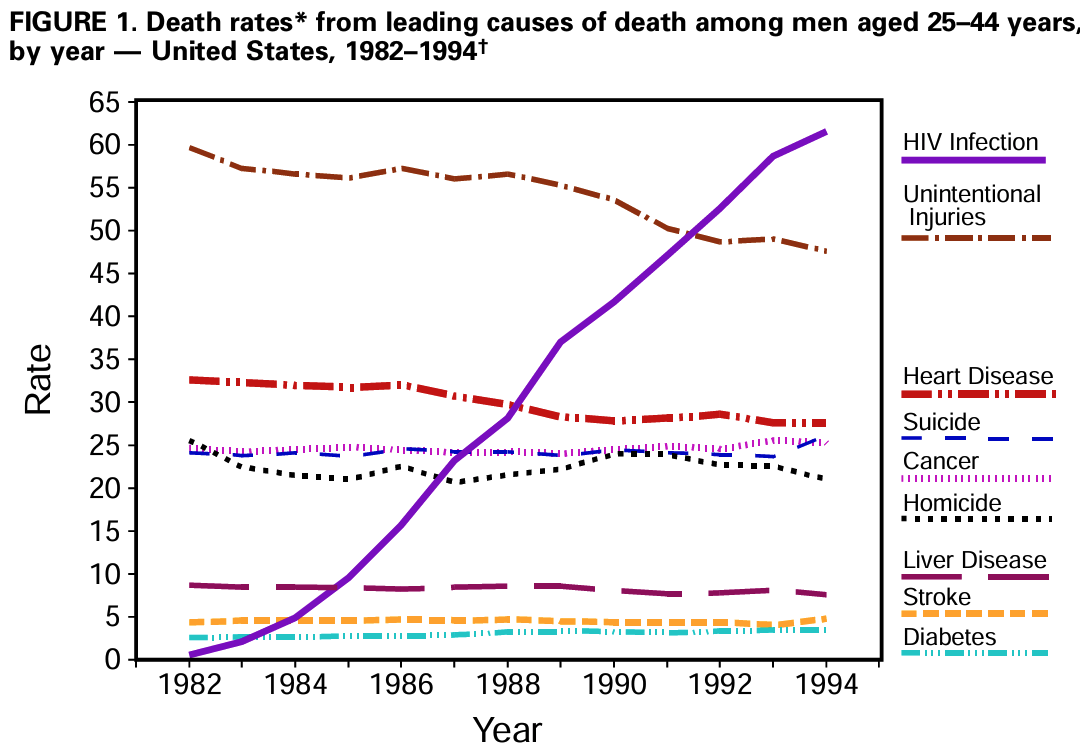

I started my internship in 1987, six years after the first cases of AIDS were reported. The median survival of someone newly diagnosed with AIDS was 12−18 months. When, at the end of my three-year residency, I chose Infectious Diseases as a specialty, part of the rationale was to follow what felt like an urgent mandate: HIV was about to become the leading cause of death among young men in the United States.

(I also liked antibiotics, microbiology, and taking patient histories about travel and pets. You know, the nerdy ID stuff.)

This catastrophic new disease taking the lives of young people in our country didn’t just present a medical challenge. The stigma was brutal. Many clinicians reinforced it by asking how someone acquired the virus, even when the information was in the chart or had no impact on treatment. “How many partners?” “IV drugs?” “Why didn’t you use condoms? I sure hope you do now.” Patients loathed the inquisition and the implied accusations; most of them already felt deeply stigmatized by their diagnosis.

One gastroenterologist, after doing an endoscopy, memorably told a 28-year-old patient of mine with candida esophagitis, “You don’t look like someone who has AIDS. How did you get it?” She remembers that 30 years later, and so do I.

It’s hard to convey just how ubiquitous, and punishing, this stigma was back then. “We can’t have those people taking up an ICU bed,” a cardiologist grumbled to me in 1990. Those people. Some surgeons looked for any excuse to avoid operating on a patient with HIV. Hospitals deliberately downplayed HIV as an area of expertise, not wanting to be branded an “AIDS hospital.”

I’m embarrassed to write that even some ID doctors followed this unfortunate plot line, expressing concern that HIV might ruin our specialty. Why take care of someone with advanced HIV disease when there was nothing that you could do to treat the underlying problem, the virus itself? Send them back to their primary providers for palliative care once you’ve treated the toxoplasmosis or pneumocystis, they argued. Small in number (fortunately), this group of ID doctors did not distinguish themselves during this period.

Because they were wrong. There was plenty we could do, and it wasn’t just diagnosing, treating, and preventing the opportunistic infections. We could also help alleviate chronic symptoms, manage polypharmacy, provide a longitudinal, compassionate care team, and — this part was critical — we could follow closely the research on antiretroviral therapy gathering steam in the laboratories and clinical trials.

When successful HIV treatment arrived in 1996, we could then celebrate with our patients the transformation of their previously fatal disease into something quite treatable. Rejoice!

Today, remarkably, HIV is easier to manage than many chronic conditions. In a quiet signal of triumph over the inevitable downward course of untreated HIV, residents who admit someone with stable HIV to the hospital — usually for a completely unrelated reason — list HIV way down on the patient’s problem list, something in the background that deserves mention but is rock-solid stable.

COVID-19: A 2-Year Siege That Drained and Divided Us

March 2020 reversed that script. Critically, this time, we ID folks weren’t alone; the whole medical center mobilized.

Energy to respond clinically was both collaborative and, at least initially, sustaining. In those first months, we worked together with critical care specialists, emergency room personnel, the microbiology lab, nursing, respiratory therapists — everyone on the front lines of patient care chipped in to get it right.

Another big difference was that, due to the mode of transmission, the fear was everywhere: every PPE donning felt like bomb-squad duty. Is it weak of me to admit that each time I entered the room of a suffering, coughing patient with COVID-19 in the spring of 2020 that my heart rate quickened? That I repeatedly checked my N-95 mask for the proper seal? Cursed with a giant nose, I had always considered this feature of my anatomy a cosmetic challenge, not a life-or-death issue — but it sure made fitting an N-95 mask difficult.

(Too much information? Sorry.)

I remember a woman from the Dominican Republic, struggling with COVID, telling me — through an iPad interpreter — that she drew strength from memories of going to church as a child. Her faith, she said, was helping her fight the virus. I listened, nodding, but from the far side of the room. The connection felt intimate; my posture and location, not so much.

Hallways were eerie and quiet — administrators were remote, many non-essential clinicians sidelined and doing only video visits, all elective surgery canceled, and family and friends of patients barred from visiting their sick loved ones. That last one was particularly heartbreaking. What a terrible time.

Then, the summer of 2020 teased us with a very welcome pause, as COVID practically disappeared from northern cities like Boston. Phew, time for a deep breath, everyone. I remember postulating hopefully, wishfully, to a close friend that perhaps the virus had already targeted the vulnerable, either from immunologic or genetic factors still to be determined; maybe it was done wreaking havoc on society at large.

I was so very wrong. The next 18 months brought us an autumn/winter surge almost as bad as the first one. Delta the following summer filled ICUs with the unvaccinated; Omicron then infected everyone else within weeks, making the Christmas holidays in 2021 a blur.

We in ID watched each of these waves unfold, following the scientific advances closely, and doing our best to communicate this knowledge to our patients and an increasingly weary public who just wanted this virus gone. Monoclonal antibody treatments came and went as the variants mutated — each antibody challenging to obtain with limited supply, and as difficult to deploy as they were to pronounce.

(It will be quite the trivia question one day to ask ID doctors to say, or spell, bamlanivimab, casirivimab, and imdevimab.)

Alas, our hard work put us in growing conflict with a world ready to move on. Anytime we modified our guidance due to evolving evidence as the disease changed, our words were seized as a signal we weren’t to be trusted. Ivermectin enthusiasm and anti-vaccine rhetoric spiraled into mass delusion. Two extremist camps battled it out in the press and social media — the group that insisted the whole thing was a fraud from the start versus those who refused to acknowledge that the disease had lessened in severity over time.

We knew that the truth lay somewhere between these two groups — yes, COVID was still with us, causing some unfortunate people to become severely ill or leading to Long COVID, but no, it was nowhere near the threat it was in the first 2 years. Somehow, conveying this message led to increasingly cantankerous pushback from both camps.

What began with a collaborative spirit to fight a global pandemic evolved into a political fracture that still hasn’t healed. It was the toughest 2 years of my career, and I’m still not over it.

Some Lessons Learned

Back to that intern’s excellent question, because in our workroom, I probably didn’t give it sufficient thought when I answered, motivating this post.

Yes, they were different. There’s no better example of how different than to look at what happened to Dr. Anthony (Tony) Fauci. Celebrated for leading the response to HIV, pilloried for the same leading role with COVID, he eventually needed a security service to protect himself and his family — one of the saddest commentaries on our divided world one could imagine.

But both viruses exposed societal ignorance and healthcare inequities. The best responses involved teamwork, compassion, rigorous evaluation of the latest research, and nuanced communication.

And both reinforced the fact that our work is never boring, that’s for sure. ID is still the best job in medicine, even when it breaks your heart.

June 27th, 2025

The Mystery of the Isolated Hepatitis B Core Antibody, Solved

(A post inspired by years of doing eConsults, an extremely common query about hepatitis B testing, and the latest BritBox series, “Core Antibody Confidential,” starring a grizzled detective with a faded suit and a haunted past.)

Your electronic medical record lists “deficiencies” in health care maintenance for one of your patients, so you order hepatitis B serologies. The next day, the results pop up on your screen (cue ominous base line):

HBsAg: negative

anti-HBs: negative

anti-HBc: positive

The start of the report was simple, but it’s the ending that pushes you to hit the “Next Episode” button.

Why? Because there’s no surface antigen to confirm an active villain. No reassuring surface antibody to declare the battle won. Just the mysterious core antibody, skulking around your labs like one of those brilliant character actors who also appeared in Broadchurch — or was it Shetland, or (changing British TV genres) Bleak House?

Let’s play the eccentric British detective, his career fading and forced to resign from a post in London due to a separate mystery on its own (and a very engaging subplot itself), and now arriving in a remote seaside town to solve this mystery.

- Resolved infection. Your patient cleared HBV long ago; anti-HBs has simply faded with time, like my memory of the names of the minor characters from Episode 1.

- Occult HBV infection. They have chronic hepatitis B, but the surface antigen is too low for detection — hiding in a witness protection program, likely somewhere in the right upper quadrant. Further inquiry with a hepatitis B DNA test (hepatitis B viral load) may snag this guy, but you’ll have to bring the patient back for more questioning … um, blood tests.

- The “window period” of acute infection. The crime just occurred, and the protective surface antibodies haven’t shown up yet, even though the surface antigen cleared. Even detectives on the downslope of their careers can chase down recent risk factors for HBV — and so should you.

- False-positive test. Tests aren’t perfect, and antibodies to hepatitis B core might cross react with other antigens — such as those triggered by eating marmite, haggis, or trifle. (Not a fan of any of these British food items, for the record. And yes, I made those up as the cause. In reality, we rarely know what triggers false positives, but low pre-test probability and imperfect assays are usually to blame.)

Practically, what to do next? And isn’t it time to stop this detective series metaphor?

(Yes. Apologies if I periodically lapse.)

Back to real life. Since by far the most likely explanation for anti-hepatitis B core antibody is resolved infection — item #1 above — the simplest thing to do is check for hepatitis B DNA. In the vast majority of cases, it will come back negative, and you can reassure your patient.

But are you done? Not quite — like any good mystery, a couple of loose threads remain, maybe even enough for Season 2. Importantly, people with isolated anti-HBc positivity may have occult hepatitis B infection (OBI), defined as HBV DNA in the liver with or without detectable HBV DNA in the blood. This becomes clinically relevant in immunosuppressed individuals, organ transplant recipients, and those with HIV or hepatitis C virus coinfection, as they are at increased risk for HBV reactivation and associated complications.

The population at greatest risk for this reactivation? People who receive B-cell depleting therapies such as rituximab, with the risk high enough to warrant antiviral therapy with either entecavir or tenofovir.

Note that this isolated core antibody pattern is particularly common in those with HIV and hepatitis C. Since most of those with HIV are already receiving anti-hepatitis B therapy with tenofovir and/or lamivudine/emtricitabine, reactivation is not a concern unless switching to a NRTI-free regimen — something increasingly done in the era of long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine. For those not on NRTIs who have isolated core antibodies to hepatitis B, periodic HBV DNA monitoring may be warranted, and I would certainly do this if the ALT and AST become abnormal.

Before wrapping up this mystery, let’s consider this important unresolved plot line:

Should people with isolated anti-HBc receive the hepatitis B vaccine?

The guidelines say yes, so clinicians who choose to do this certainly are taking a defensible position. There may be institutional or documentation-based reasons to vaccinate — fair enough. And you’d make the guidelines happy.

But in terms of virologic logic? Count me unconvinced. I’d argue that since the primary purpose of the hepatitis B vaccine is to prevent viral acquisition, what’s the point of vaccinating people who have already had hepatitis B?If there were convincing clinical studies demonstrating that those with isolated anti-HBc are at high risk for infection with de novo hepatitis B virus, then I’d be more enthusiastic. But I can’t find any.

Also, as far as I know, there aren’t even studies showing that giving the vaccine reduces the risk for reactivation of occult HBV — only studies that look at antibody responses after vaccination. Some respond, some don’t.

To quote one expert on viral hepatitis, University of Washington’s Dr. Nina Kim:

Bottom line: We don’t have but need longitudinal data showing that vaccination actually helps this subset of patients.

Agree 100%!

Take the poll, folks.

Now watch Nina’s great educational lecture on this mysterious serologic pattern, and come back for this classic.

June 20th, 2025

Federal HIV Guidelines Face a Shutdown — A Critical Loss for Clinicians and Patients

Each week, our HIV clinical group gathers to review active patients, share updates, and celebrate good news. On our whiteboard, we list four columns: Inpatients, Outpatients, Issues, and Celebrations.

Each week, our HIV clinical group gathers to review active patients, share updates, and celebrate good news. On our whiteboard, we list four columns: Inpatients, Outpatients, Issues, and Celebrations.

This week, under “Issues,” one of my colleagues wrote:

HIV Guidelines: ☹️

Yes, you read that right. This week, we learned that the federal HIV guidelines — long the most cited national standard for clinical care — may soon lose NIH support. Here’s what the official letter said, shared with me by a current panel member:

After careful consideration, leadership at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has determined that NIH support provided by the Office of AIDS Research (OAR) for the HIV clinical practice guidelines will phase out by June 2026. In the climate of budget decreases and revised priorities, OAR is beginning to explore options to transfer management of the guidelines to another agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

The key phrase here is “in the climate of budget decreases and revised priorities,” which basically means someone has decided that the national standards for HIV treatment aren’t worth spending money on. Let’s think about this for a nanosecond — how much money is this really saving anyone?

And the “options to transfer management of the guidelines to another agency” face big-time challenges. I have it on good authority from people at HHS that it is highly unlikely any existing agency has the available time or expertise to take it on.

Meanwhile, it’s worth reviewing just how valuable these guidelines have been in establishing an informed, evidence-based standard for HIV care in our country. A historical perspective with some notable milestones:

- First OI prophylaxis recommendation (TMP-SMX for PCP)

- First perinatal guidelines, post-ACTG 076

- First ART guidance responding to the era of combination therapy

And they’ve kept going. Responding quickly to practice-changing studies, these guidelines have truly been a “living document,” publishing updates on a regular basis in a way that would be impossible for most journals.

A disclosure: I contributed to the Opportunistic Infections Guidelines (Bacterial and Respiratory working group) and served on the HIV treatment panel from 2008 to 2016. What impressed me most was the care, rigor, and collegiality of the process. Every recommendation was debated, refined, and re-reviewed, always with the goal of helping clinicians deliver the best possible care.

(For the cynics: Panel members volunteered their time. Translation — we were unpaid.)

The NIH staff overseeing the process had deep expertise in the field and kept the process moving along with an uncanny ability to attend to multiple voices. Plus, they were meticulous about details in a way that card-carrying ID types like me find very reassuring. Remember, many of us exhibit a clinical form of OCD that translates into our history taking and notes. Just the other day, I read a colleague’s note that started with the word “briefly” — and then went on for a thousand words, give or take.

Another disclosure: I now participate in another guidelines group, headed by the IAS-USA. In doing so, one might ask why have two existing sets of guidelines? I’d argue that having alternative voices in this process — one that includes international contributions — enhances the usefulness of both guidelines.

It’s not clear what will happen to the federal HIV guidelines going forward. A discussion about the “transfer” options is planned during an upcoming Office of AIDS Research meeting on June 26. The guidelines discussion will start around 2:15 p.m. ET, with the public comment period scheduled for 3:25 p.m. ET. If you think the guidelines have been important, and worth saving, I encourage you to provide public comment, or email OARACinfo@nih.gov directly.

Now back to the frowny face emoji at the top of this post. I can’t help but connect this decision to another recent action: the abrupt firing of ACIP members. Both seem to reflect the same troubling sentiment we heard not long ago from the current HHS leadership — a desire to “give infectious diseases a break for eight years.”

Why should that break include eliminating something that works this well, and that clinicians actually use? Frustrating.

For the record, if you’re wondering what landed in the “Celebrations” column on our whiteboard this week — it was the graduation of our ID fellows.

Here are two of our stellar grads, making me optimistic about the future of infectious diseases, “break” or no “break.” Congratulations, Cesar and Gaby! And thank you for sharing the photo.

Me with two future ID clinical leaders; photo posted with permission. (I’m the old guy in the middle.)

June 12th, 2025

Why the Sudden Firing of ACIP Members Should Put Every Clinician on High Alert

Public health poster, Herbert Bayer, 1949.

There are certain irrefutable verities when, like me, you’re an infectious diseases specialist married to a pediatrician. Here are our top two, which are deeply interrelated:

-

Infectious deaths in children, or severe illnesses that lead to lifelong disability, are more devastating than similar events in adults. Each such case in a baby or child is so very tragic. I’ll again quote Dr. Burton Grebin: “To lose a child is to lose a piece of yourself.”

-

The success of vaccines in preventing those deaths and illnesses stands as one of the great accomplishments of modern medicine.

Seen a case of Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in a kid lately, one so severe they have permanent deafness or other neurologic sequelae? The same bug causing epiglottis, forcing a child to lean forward, afraid to talk and struggling to breathe? Bad rotavirus diarrhea in a baby, leading to that awful look of sunken eyes and the clinical descriptor, “floppy”? Whooping cough in an infant who can’t catch their breath? Or measles complicated by pneumonia or encephalitis that required hospitalization?

Thanks to vaccines, even busy clinicians rarely if ever see such cases today. As I’ve noted here before, if you combine the total number of cases of measles seen by my wife and me in our cumulative decades of practice, you’d fit that number on one hand, and have a couple of fingers left over. And we’ve witnessed first-hand the near disappearance of invasive disease from Haemophilus influenzae, severe varicella, and rotavirus disease.

It’s no wonder, then, that when the nomination of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. to head the Department of Health and Human Services began circulating, my wife and I watched the proceedings with intense interest, and rising dread. I naïvely hoped that Sen. Bill Cassidy, a physician himself and ranking member of the Senate HELP Committee, would do the right thing and block the nomination, as he shared his concerns about Kennedy’s anti-vaccine views during the nomination process.

Alas, he did not block the appointment. In fact, he issued a statement explaining his support, citing Mr. Kennedy’s assurances that he would preserve the existing vaccine infrastructure:

He has also committed that he would work within the current vaccine approval and safety monitoring systems, and not establish parallel systems. If confirmed, he will maintain the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) without changes.

Emphasis mine — because earlier this week, Kennedy announced the removal of all current members of ACIP. So much for those assurances. Yesterday, he replaced them with eight new members of varied backgrounds, some of whom clearly share his skepticism about the benefits of childhood vaccines.

His stated motivations for the firings, rife with misstatements and oversimplifications, reveal a profound misunderstanding of how ACIP works. It also provides a glimpse into Kennedy’s longstanding distrust of vaccine safety and efficacy.

Let’s be absolutely clear: ACIP was a group of unpaid vaccine experts who based their recommendations on clinical data, safety monitoring, disease surveillance, and cost-effectiveness. They were not shills for the pharmaceutical industry. They were not political actors. Their deliberations were public and open to commentary. For years, their work has been critically important in shaping policy and ensuring insurance coverage for vaccines in our byzantine healthcare system.

What policies will we get from the new panel? More importantly, what will be the health implications for our society? Time will tell — an ACIP meeting is planned for later this month, and their actions should be watched closely by pediatricians, ID specialists, and indeed all clinicians. Already, alarmist headlines predict dire health outcomes ushered in by this regime change, and many of us worry it will further undermine confidence in vaccines that are of critical importance to childhood health. We’ll see.

But one thing is certain: For anyone who expected that Kennedy would “maintain the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) without changes,” this week’s events are a clear reminder that actions speak louder than words.

June 6th, 2025

How ID Doctors Get Paid, Part 3: The Grab Bag Edition

Get yours today.

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations! You’re now deep into the ID Reimbursement Rabbit Hole. Part 1 and Part 2 covered how ID doctors contribute immense value through patient care, stewardship, infection control, travel clinics — proudly fighting along the way for appropriate compensation as the “Loss Leaders” of the hospital.

(Did you get your emblazoned fleece vest yet?)

Before going on, however, I’d like to address the ongoing concern that discussing payment is somehow unseemly. That discomfort with discussing money is understandable — especially given the bloated costs of American healthcare and our field’s patient-centered mission, with care often delivered to people who are disenfranchised or stigmatized.

As a result, it’s very “on brand” for ID in particular to avoid these discussions. As my colleague Dr. Daniel Solomon put it when I floated the idea for this series:

It is tough to talk about money in some crowds. Especially (paradoxically) some ID communities. As much as I love our field, there is an overrepresentation of people in ID who seem to judge such discussions harshly.

Yep. But in defense, if we don’t talk about it, how can we expect things to change? Very much appreciate Dr. Alice Han’s comment in response to Part 2.

So let’s wrap up with Act 3 of the show, a miscellaneous grab bag of other areas for salary support.

7. Infusion services. Free-standing ID practices can offer infusion services, where patients can receive intravenous dalbavancin or daptomycin or remdesivir or you-name-it. Of course, this takes up-front investment in clinic infrastructure, deft administrative support to obtain prior approvals for expensive drugs, as well as purchasing and storing the medications. I’ve furthermore heard that the revenue is tightly tied to the cost of the drugs (dropping for many IV antimicrobial agents as they go generic) and the quality of a patient’s insurance.

Still, one ID doctor reached out to me a to share how much his patients appreciated the service — and how profitable it was for the practice. Even with declining drug margins, his nimble outpatient ID group leveraged infusion services to reduce hospitalizations and ED visits, which payers (and patients) appreciated, the former paying them to keep it afloat.

But if, like me, you work at a hospital, the outpatient infusion center is run by the institution. Most of their treatments are regularly scheduled immunosuppressants (for rheumatology, GI, neurology, etc.), chemotherapy (if a cancer center), and immunoglobulins. We occasionally bug* them for outpatient parenteral antibiotics, but none of the revenue flows back to the ID doctors.

(*See what I did there?)

8. Pharmacy. If a clinic or hospital provides “safety net” care to a sufficient proportion of people, they may be eligible to participate in the 340B pharmacy program. This allows pharmacies to purchase the medications at a discounted price, but charge the usual price to payers, with the difference set aside to cover the care of patients who are socially or financially disadvantaged.

For ID clinics that care for large numbers of people with HIV and have an affiliated pharmacy, the 340B program can be a financial savior. In fact, for some clinics, it’s their largest source of revenue, supporting not only ID physician salaries but also nursing, pharmacy, and case management.

Unfortunately, this isn’t universally true. Some institutions retain all 340B revenue (while simultaneously claiming that the ID clinic is a “cost center” — ouch!), with none of it going to ID. That’s … not what the program was designed for.

(Brief aside — did you know that the 340b program may be partially responsible for the ongoing high price of HIV drugs? Think about it — the higher the price, the bigger the net return for a 340b pharmacy, hence there’s an incentive to keep the prices high. It’s hard to find something in our bizarre American healthcare system that surprises people from other countries, but when I told them about this aspect of the 340b program, it certainly caused some head scratching.)

9. Industry-sponsored clinical trials. I originally intended to leave all research activities off this guide of how ID doctors get paid, as it felt more related to academic medicine in general rather than ID in particular. After all, successful physician researchers often have grants that cover 80% or more of their salary.

But Ron Nahass pointed out to me that industry-funded clinical trials are different; they’re available to a broader range clinical ID doctors who would only consider themselves part-time investigators at most. They also pay per enrolled participant, not for protected time. Note that companies running these trials often look outside of academic medical centers for their highest-enrolling sites, and also appreciate what is usually a more efficient processing of contracts and other paperwork.

So, briefly: for practices with the infrastructure to support them, industry-sponsored trials can both benefit patients and generate income to support ID clinicians. Trials can offer access to novel treatments, cover travel and parking, and even provide stipends to compensate patients for their time. For some patients, participating is also a way to “give back” to a specialty that has helped them, or because they’d like to play a role in advancing the field. It is amazing — and quite humbling — how altruistic some people are about signing up for research studies solely for this reason.

So that covers some of the major sources of salary for US-based ID doctors, leaving aside support they might get from research grants, teaching at an affiliated medical school, or administrative roles. For more reading on this topic, here’s a link to this remarkable Reddit thread from the residency subreddit about choosing ID as a specialty, which I found fascinating:

To sum up the comments: we don’t go into ID for the riches — but we love what we do!

Last dog video (of the series):

What an impressive jumper! I love how calm Sounders is when being “interviewed” on camera between jumps

May 31st, 2025

How ID Doctors Get Paid, Part 2: Infection Control and Other Invaluable (but Often Invisible) Work

Before getting to today’s main topic, allow me a brief protest — three recent vaccine-related actions that reek of profound (and misguided) vaccine distrust from HHS leadership.

Before getting to today’s main topic, allow me a brief protest — three recent vaccine-related actions that reek of profound (and misguided) vaccine distrust from HHS leadership.

They are:

- Cancellation of a grant to develop an H5N1 vaccine. Preparation for this looming pandemic threat is critical, and there’s arguably no better way than having a vaccine ready.

- Removal of pregnant women as eligible to get a COVID-19 vaccine. This, despite their inclusion in the recent FDA decision. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) immediately protested.

- Ending a program developing an HIV vaccine. Just because something has been scientifically difficult, or has primary benefits in other countries, doesn’t mean the research agenda should be abandoned.

So painful.

(Deep breath.)

Ok, on with the main topic of today’s post. In Part 1 of this series, I described how ID doctors earn their income through direct patient care — consults, outpatient visits, and (less commonly) procedures. But clinical care is not the only source of salary support for our specialty. In this installment, I turn to the ways ID specialists support hospitals and healthcare systems. This work is often essential for optimal patient care but is frequently undervalued.

4. Agreements to provide critical hospital patient-care–related services. The most common are payments from hospitals to ID doctors to manage infection control and antibiotic stewardship programs, as these are required services in every hospital. Less often, an ID doctor might provide clinical advice (as a consultant) to the microbiology laboratory. For some ID doctors, these activities comprise a significant portion of their salary.

Similar agreements can sometimes be negotiated for other patient-specific activities — for example, at our hospital, we have payments to support care of patients with HIV (salary support is distributed to doctors, nurses, social workers), people with cancer- or transplant-related infections, and patients on outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT).

(For years, we did OPAT with no funding. I strongly advise anyone doing this now for free to do what we ultimately did — state you’ll stop providing this critical service unless it can be appropriately supported financially. Then set a date, and let the orthopedic surgeons, cardiologists, or whoever wants to discharge a patient on OPAT know they’ll be managing it themselves. If you’d like to read more about the hot potato of OPAT, I’ve got you covered.)

We used to have a contract to provide ID care and support for an affiliated community-based group practice, one owned by an HMO (remember those?). Two of us staffed a nearby clinic once a week, and just as importantly — since we weren’t on site full-time — we were funded to provide medical back up their outstanding nurses, who focused on ID/HIV care and fielded questions from our patients. I really enjoyed that work, especially the long-term patient relationships and collaboration with such a skilled nursing team. But when the HMO ended its affiliation with our hospital, the contract vanished too. Poof, decades of relationships, gone. Sometimes, the business side of medicine hurts.

5. Telehealth. Given the shortage of ID doctors, especially in rural areas, some hospital systems employ ID doctors to provide ID consultations remotely to affiliated hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and skilled nursing facilities. The consultations can take the form of telehealth consults directly with patients (with on-site providers giving more of the medical history), or clinician-to-clinician advice, with the caveat that the latter has little in the way of reliable billing options. (As I’ve noted a billion times. But who’s counting.)

Among academic medical centers, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) was a leader in this telehealth activity — even before the pandemic — and two of our ID fellow graduates partially support their salary through this work. Notably, UPMC had a strong incentive to develop telehealth since their network extended far beyond the city of Pittsburgh. For both patient convenience and cost, it made more sense to pay ID doctors for telehealth than to put the patient in an ambulance and bring them to the main campus for care.

Outside of academic medicine, private companies offer telehealth services throughout the country and some provide ID-specific care — one notably started by an ID specialist, Dr. Javeed Siddiqui.

6. Travel clinics. Since insurance does not cover many travel-related vaccines, some ID doctors own or work in travel clinics that are cash-first businesses, catering exclusively to a self-paying (and usually well-to-do) clientele. To quote Dr. Ron Nahass, who is not part of one of these clinics, and how they fit in our healthcare system: “It is a consumer product, not a medical service.” An amazing but true fact — many of these clinics won’t do an evaluation of someone returning from travel with an illness, but refer them to ID clinicians like us!

Importantly, this revenue model does not apply to all travel clinics. Many ID doctors who specialize in travel medicine work in nonprofit settings and provide excellent and comprehensive pre- and post-travel services — including evaluations of travel-related infections. Unfortunately, in certain academic medical centers, it can be a struggle to make them work financially for a variety of arcane billing reasons. I’m aware that some have had to close based on losing money, despite the important and in-demand service they provide.

That wraps up Part 2 (after that painful vaccine news up top). As a consolation, here’s the promised dog video. Will Pepper get a call-up to the show this season?

In Part 3: infusion services, pharmacy programs, industry-sponsored trials, and other creative ways ID docs try to keep the lights on. Stay tuned.

May 22nd, 2025

The Pros and Cons of the Latest FDA Actions on COVID Vaccines

Figure from Edward B. Foote’s Plain Home Talk, 1896.

In case you missed it, last week the FDA granted full approval for the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine. This vaccine, which uses a more traditional protein-plus-adjuvant strategy instead of the mRNA approach of Pfizer and Moderna, is no longer in “Emergency Use Authorization (EUA)” limbo.

Here’s what that means in practical terms:

- It shows the data the company submitted were sufficiently favorable from a safety and efficacy standpoint to merit full approval.

- Insurance should now cover it for indicated use — something not guaranteed before.

- The vaccine should be more broadly available. The limited availability under the EUA meant that some people who wanted an alternative to mRNA vaccines chose not to get a COVID vaccine at all.

- The company can now legally engage in promotion (not so good) and education (good!). But it’s remarkable how few people even knew that this vaccine existed, so I’ll take this as net positive.

All good news, right? Especially since data suggest this vaccine has fewer side effects than the mRNA options. Plus, there’s a combined Novavax COVID/influenza vaccine in development that could be especially appealing to people eager for seasonal updates.

However, approval alone doesn’t tell the whole story. Much of the news coverage was on the notable limitations on its use — a strong signal we’re in a different phase of the pandemic, where regulatory decisions reflect shifting risk-benefit calculations. Specifically, the Novavax vaccine is indicated only for adults 65 and older, and for people ages 12–64 with at least one underlying condition that increases the risk of severe COVID-19.

And it isn’t just Novavax. These same limitations were soon applied to the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines as well, a coordinated move by the FDA that highlights a new, more selective era for COVID vaccine policy under new FDA leadership, and one that brings us more in line with recommendations in other countries. The rationale for these changes is summarized in a NEJM Sounding Board authored by Drs. Vinay Prasad and Marty Makary from the FDA.

This narrower indication might sound like a step backward, but it’s worth considering what it practically means: First, these changes reflect a shift in COVID clinical severity from the first 2 years of the pandemic, and not a repudiation of the vaccines’ value from the original studies. The proven efficacy of the mRNA vaccines in preventing severe disease in a population naive to SARS-CoV-2 was one of the most breathtaking scientific advances in my now lengthy career.

But now, nearly 5 years later, with essentially 100% of the population already vaccinated or previously infected or both, the virus causes less severe illness on average. As a result, the risk-benefit calculation for routine COVID boosters in younger, healthy adults has changed.

Second, it doesn’t mean younger people can’t get a COVID vaccine. The CDC list for higher risk conditions is extraordinarily inclusive: a telephone survey of nearly 450,000 randomly selected U.S. adults 18 years of age or older suggests that a high proportion would meet these criteria. Many people in the younger than 65 age group will be eligible.

And if they don’t have any of these conditions? Clinicians can still offer the vaccines off-label, much like they can for HPV (Gardasil) and herpes zoster (Shingrix), two vaccines that also launched with clearly restricted age indications placed by the FDA.

For the record, clinicians and the public alike have intuited this risk-benefit shift in COVID vaccines, and voted with their feet (and deltoid muscles). Uptake of the annual booster vaccines is low, with less than 25% of Americans receiving the shots each year. I know many otherwise quite pro-vaccine providers who recommend the vaccines to their patients with little enthusiasm. It even extends to my ID tribe and to other healthcare workers; as one colleague told me in an email as we discussed the FDA’s shift:

I stopped getting it this year because it gives me side effects that are definitely as bad as COVID itself.

Not surprisingly, the FDA’s new policy has drawn criticism from some in the medical and public health communities, including some of my colleagues. And indeed, they have some very legitimate concerns. These range from the potential for reduced access or coverage among people who still want the vaccine but now must receive it off-label, to broader worries about the message it sends regarding the importance of vaccines in general.

(Notably, the authors of the NEJM Sounding Board highlight the importance of the measles vaccine — an especially timely endorsement given the widely publicized skepticism of the head of HHS about this critically important strategy for childhood health.)

Some have also argued that decisions about vaccine policy belong with the CDC and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), not with the FDA, whose primary charge should be safety and efficacy. One vaccine expert told me this conflict reflects a broader problem with our fragmented vaccine governance — a good point. For the record, I very much continue to value ACIP’s expert input, and eagerly await it in light of this FDA decision, noting that they were already considering making similar changes.

A final point of disagreement is the importance of the observational data in informing our decisions. One of my colleagues forwarded me one such study, showing that people who got a seasonal booster were less likely to get COVID and less likely to experience serious hospitalizations. Implied in these data is that people who get the vaccine might be less likely to transmit the virus to others — no infection, no transmission. A further strength of these studies is that they reflect how vaccines perform in real-world clinical settings, not just controlled trials

The problem with observational studies like these is that people who choose to get COVID vaccines undoubtedly differ from those who do not, differing in ways that could easily influence the outcomes of interest. No amount of statistical manipulation can completely eliminate this residual confounding. And the issue of reducing virus transmission, though laudable, did not play a role in the recent approval of the RSV vaccines (which also have FDA-imposed age limits). One doesn’t administer an RSV vaccine to someone who is younger and immunocompetent because they’re spending a lot of time with older adults, or a person who is immunocompromised.

So where does that leave us? As noted by the authors of the NEJM Sounding Board, what we really need is a trial of COVID vaccines in healthy adults.

This should not be a quick study measuring post-vaccine antibody titers, but a rigorously blinded clinical trial that collects both efficacy and safety data. The results would tell us if these vaccines meaningfully reduce symptomatic disease in this lower-risk group, and whether the benefit is worth the potential side effects. Think of how much more informed our counseling of healthy adults would be! My colleague, who opted out last year and is neither over 65 or immunocompromised, would know whether getting the vaccine actually benefits her health — and also know how to counsel her patients.

(Hey, while we’re at it — what about a three-armed blinded trial comparing the available vaccines in older adults? Or in immunocompromised hosts? We can dream, can’t we?)

The FDA’s view on the need for more clinical trials, by the way, is shared by the previous director of the FDA, Dr. Robert Califf — so this isn’t just this new FDA leadership making trouble. Here’s Califf writing in JAMA earlier this year:

As the majority of US residents are declining the opportunity for COVID vaccination and many clinicians have elected not to press the issue, COVID vaccine uptake is now low enough that large RCTs [randomized clinical trials] are feasible to evaluate the efficacy and safety of new updated boosters. These trials could help to further elucidate benefits and risks in the current environment in which most people have some level of immunity due to previous infection, previous vaccination, or both.

Sounds to me like equipoise — just what we want with a clinical trial! A favorable result, with reduced symptomatic disease in the vaccine group compared to placebo, would clearly influence both guidelines and clinical practice. Conversely, if the vaccine has more adverse effects and doesn’t meaningful reduce disease, then this is also important information to know.

Back to Novavax, which fills an important niche. Not everyone wants an mRNA vaccine, whether due to side effects (raises hand!), concerns about the technology, or simple personal preference. Having an alternative that’s now fully approved — with fewer systemic side effects and a path to broader visibility — is good news for both individual choice and public health.

It’s easy to focus on what’s not included in the latest announcements — no guarantee of universal access, no new variant-specific updates, no big press conferences. But maybe the normalization of COVID vaccination policies to be more in line with international standards, including thoughtful guidance and a call for better data, is exactly what we need right now.

May 18th, 2025

How ID Doctors Get Paid — The Bread, Butter, and Budget Deficits of Infectious Diseases

“The Vanishing Family Doctor,” by Mary B. Spahr, 1947.

Two decades ago, Dr. Atul Gawande wrote a memorable piece for The New Yorker about how doctors in the United States get paid. Providing a nice mix of self-reflection about his own experience and some skillful reporting, he described the challenging process of figuring out what he, a newly hired surgeon, should earn for a salary.

Why challenging?

Most people are squeamish about saying how much they earn, but in medicine the situation seems especially fraught. Doctors aren’t supposed to be in it for the money, and the more concerned a doctor seems to be about making money the more suspicious people become about the care being provided … Yet the health-care system, as I soon discovered, requires doctors to give inordinate attention to matters of payment and expenses.

Isn’t that the truth? After years of sacrifice — medical school (usually with debts), residency, subspecialty training — it’s time to get a job, and to get paid. So knowledge of what sort of things comprise a salary plays a big role in career planning, even for those toward the bottom of the physician payment scale.

Or maybe I should say especially for those of us at the bottom of the pay scale. You know — us.

I thought of Gawande’s piece because the other day, I was chatting with someone in hospital administration who is relatively new to issues of clinical reimbursement in ID. I thought she might benefit from a primer on how ID doctors earn their salary, particularly through patient care and related activities — hence this three-part* series on how we actually earn a living. I’m leaving out other potential sources of income (grant-funded research, administration, teaching, consulting, medicolegal work) because that’s a whole different topic, but these too can support or supplement a person’s salary.

(*Yes, three posts. The first draft was gargantuan, and one must respect the precious time of brilliant-but-busy readers!)

And caveat emptor, I’m an ID doctor at a US-based academic medical center, so some of my comments might be irrelevant, or not applicable, to practitioners in private practice, or those of you reading from countries with different medical systems — and little to no medical school debt. Because of this limitation, I reached out to Dr. Ron Nahass, Medical Director at ID Care, a large, multisite private practice in New Jersey, and Dr. Brad Spellberg, Chief Medical Officer at the Los Angeles General Medical Center, who provided very useful feedback before I posted this.

Here’s the start of the list — basic patient care. In Parts 2 and 3, I’ll cover some other common salary sources for consideration:

1. Consults on hospital inpatients. For most ID doctors, this is the primary source of their clinical income. The more consults, and the higher the complexity of the consults, the more revenue. It’s the same as with procedural-based clinicians and surgeons but, of course, much less remunerative. Still, the more you see, the more you earn.

Note that most ID doctors in academic medical centers are salaried, so the relationship is blunted or, ironically, not present at all. More consults just means you’re busier, not that you’re paid more. Incentive programs to salaried physicians can encourage ID doctors to see more patients, but these may be canceled out by accounting that shows we ID doctors are being paid more than we earn. Talk about a dispiriting message from an institution — Even though you’re really busy, you’re costing us money.

Given the above information, ID doctors have mixed feelings about “curbsides” — informal advice given to clinicians. On the one hand, we want to be collegial, improve the efficiency of care, and help. Salaried doctors may even view them as shortcuts to completing the day’s work more efficiently.

On the other hand, each curbside deprives ID doctors of income (especially in private practice), they take time, they are interruptions, the information could be relayed inaccurately, and there’s some medicolegal risk. There should be a system that supports the time and expertise required to formally advise other clinicians, but those that exist are mostly limited to outpatients, offer meager pay, or don’t exist at all. And yes, I’m obsessed with this topic!

2. Outpatient care. Outpatient care can reimburse at the same level as inpatient consults, but it’s arguably more difficult, both from the perspective of patient diversity and the infrastructure (support staff and real estate) needed to make it work financially. Unless you have someone helping with prior authorizations for unusual drugs (isavuconazole or omadacycline spring to mind first), scans (PET CTs for fevers of unknown origin), or tests (Karius, I’m looking at you), you will be quickly buried by non-physician work.

In addition, care is more likely to spill over into non-clinical hours as you follow up on tests and communicate with patients. For the vast majority of doctors, interactions with patients via telephone and electronically through patient portals reimburse nothing — despite the fact that these communications are a critical component of good patient care, and take time to do well.

In other words, there’s a reason that a high proportion of ID doctors greatly limit their outpatient hours, or in many cases, don’t do outpatient care at all. It’s hard clinically — and even harder to make it work financially!

3. Procedural activities. One of the primary reasons ID doctors choose the specialty is because of the cognitive nature of the work. As a result, most of us do few if any procedures, which suits me just fine — though, of course, it sometimes is frustrating to hear that a dermatology visit with a skin biopsy that last minutes reimburses as much as an hour-long outpatient ID consult on a fever of unknown origin.

Here’s a memorable example from Gawande’s New Yorker piece:

In the mid-eighties, doctors who spent an hour making a complex and lifesaving diagnosis were paid forty dollars; for spending an hour doing a colonoscopy and excising a polyp, they received more than six hundred dollars.

Amazingly (at least to me), a small proportion of ID doctors have training in certain outpatient procedures, and do them regularly — skin biopsies, wound management (debridement and cauterization), simple dermatologic procedures, high-resolution anoscopy. One of them is a close colleague of mine, and she told me she always loved doing procedures during her medical residency. Not your typical ID doctor!

Before wrapping up this direct patient-care category, I must share an important (and depressing) fact about ID in a mostly fee-for-service world. Quoting Brad here, offering perspective from hospital administration:

In a fee-for-service world, ID is always going to be a loss-leader. ID does not bring in business to hospitals. Surgeons and proceduralists do. That’s where the money is in a fee-for-service world. The role of ID therefore is to support the surgeons and proceduralists. Even in internal medicine, ID is in a supportive role, supporting the hospitalists. People often talk about how ID improves outcomes and care. But those things just aren’t paid for. The pay in a fee-for-service world is for the surgery, procedure, or admission to the hospital.

Oh well. Brad has eloquently written about this problem in ID, and the challenges are especially acute in large academic medical centers, where ID divisions frequently run budget deficits and rely on more flush clinical services for subsidies.

Maybe we should we all get fleece vests to wear at the hospital, emblazoned with the text:

ID: Proud Loss Leader

Sigh. So in Part 2, I’ll cover how ID doctors support hospitals, sometimes get paid for it, and sometimes… don’t.

Hope this is interesting. As a compensation for going on this journey with me, I’ll finish each one with a remarkable dog video, so at least you’ll have that.

https://youtube.com/shorts/j7b-ref2XTE?si=_R3rMbIge5zHF191

May 7th, 2025

FDA’s Latest Appointment Is … Interesting

Those of us who follow infectious diseases and vaccine science closely (OK, obsessively) know that the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) plays an enormous role in public health. Vaccines, gene therapies, monoclonal antibodies, blood products — all pass through CBER on their path to approval. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this center became a household name under the steady leadership of Dr. Peter Marks, who has long championed rigorous scientific review combined with clear communication to the public.

Those of us who follow infectious diseases and vaccine science closely (OK, obsessively) know that the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) plays an enormous role in public health. Vaccines, gene therapies, monoclonal antibodies, blood products — all pass through CBER on their path to approval. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this center became a household name under the steady leadership of Dr. Peter Marks, who has long championed rigorous scientific review combined with clear communication to the public.

Now comes news of a major change. Dr. Vinay Prasad, a highly visible (and often polarizing) physician, scientist, and commentator on medical evidence, has been appointed to lead CBER.

To call this appointment interesting barely scratches the surface.

I first learned about Vinay through his social media activity on what was once called Twitter, may it R.I.P. His attention-getting posts on COVID-19 reflected someone brilliant, analytically rigorous, prolific, and passionate about improving the way we generate and apply medical evidence.

When the RECOVERY trial released data showing dexamethasone’s survival benefit, and the investigators made the protocol immediately available, he urged us to adopt the findings right away — not to wait for the (inevitably slower) publication.

He loudly and repeatedly criticized prolonged school closings, correctly identifying that vulnerable populations — kids attending public schools, especially those from less affluent families — would bear the brunt of the delays in learning and social development.

He also flagged with alarm the rare but serious clotting side effects of the Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca COVID vaccines, issues that ultimately contributed to their withdrawal.

And he pressed for better evidence on community masking mandates. He found the data wanting — and let’s face it, masking (especially outdoors) eventually became more a political signal than a meaningful infection control strategy.

So persuasive was Vinay on these and other issues that I invited him on the Open Forum Infectious Diseases podcast, where he gave what one colleague described as a “hyper-caffeinated” take on the pandemic. No one has come close to his words-per-minute record. A high bar!

In short, he has made a career challenging dogma and questioning medical practices that are adopted with too little critical scrutiny. These qualities — intellectual sharpness, a relentless drive to improve science — will serve him well in this important job.

But there’s another side.

Vinay also embraces a confrontational style, especially in public forums. His sharp critiques can sometimes alienate as much as they illuminate. And in the nuanced and emotionally charged world of vaccine policy, that carries obvious risks. Vaccines aren’t just scientific products aiming to improve health anymore — wouldn’t that be nice? They’ve become flashpoints in public trust, political identity, and social discourse. Navigating this terrain requires careful engagement, deep listening, and collaboration with a wide range of stakeholders.

While I respect Vinay’s formidable intellect, I hope he brings his best and most collaborative self to CBER. We need a leader who values respectful dialogue, embraces uncertainty when necessary, and sees scientific regulation as a team sport — and not a zero-sum game or a chance to attack others.

For context, I also know Peter Marks and respect him enormously. He shepherded CBER through COVID-19 with grace and steadiness, during a time of tremendous uncertainty and societal anxiety, and often under intense political pressure. I am especially concerned about the reasons he has given for departure, which likely reflect growing tensions within HHS and a troubling and stubborn anti-vaccine sentiment at high levels.

Ultimately, my deepest hope — and I suspect everyone’s — is that this appointment of Dr. Vinay Prasad leads to a continued focus on improving the safety, efficacy, and public trust in biologics, especially vaccines. We need rigorous science, honest communication, and thoughtful leadership more than ever.

Before publishing this, I plan to share the post with both Peter and Vinay — partly as a courtesy, but also because I believe that transparent and respectful dialogue starts with how we talk about each other.

The stakes, after all, could not be higher.