An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 21st, 2019

AIDS Conference Returns to Mexico City, Where We Saw an Underrated, Great Advance in HIV Therapy

If you’ve been an ID or HIV specialist for only a decade or so, the following statement might seem unfathomable to you:

Until 2008, there were lots of people with HIV whose medication adherence was perfect — but they still had virologic failure.

How could that be? The simple answer is that their virus had too much resistance to the then-available drugs.

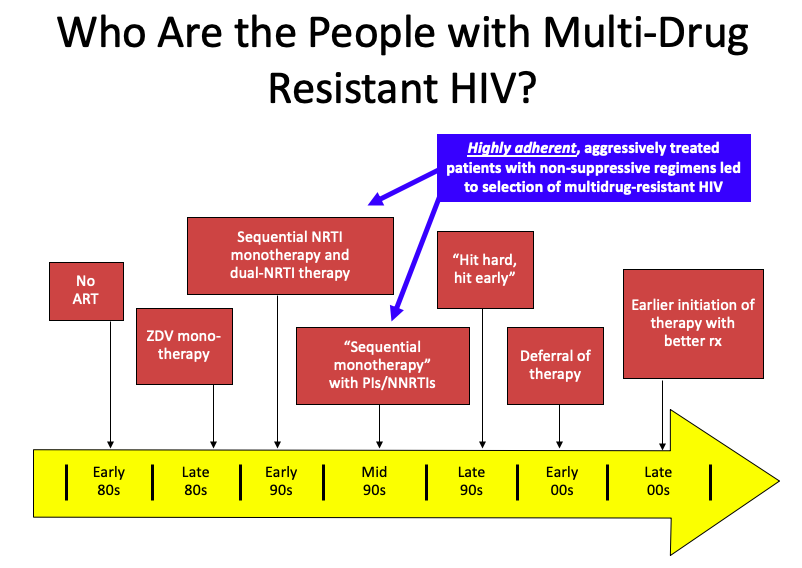

But it’s a bit more complex than that. Several factors converged, summarized in this PowerPoint slide:

(I once upon a time thought this slide originated with Steve Deeks — but now he denies creating it, so I’ll take “credit”. Hey, good slides are like recipes, incrementally adapted until they become your own. If the originator wants to come forward, I’m happy to add your name to the slide.)

It’s those people in the blue box that have the most extreme multi-class HIV drug resistance. Treated in the early-1990s with single or dual nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), they already had NRTI resistance when the protease inhibitors (PIs) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) because available in the mid-1990s.

Addition of a single active drug from these classes, often of marginal potency (nevirapine, delavirdine), or suboptimal pharmacokinetics (saquinavir, nelfinavir), or toxicity (ritonavir) acted as “sequential monotherapy”.

What we know now is that if they didn’t also add lamivudine as a new drug (which was still very active against most NRTI-resistant virus at the time), they were likely to experience treatment failure, with resistance to yet another drug class.

It didn’t help that we didn’t fully understand within-class resistance — for example, it was believed that the resistance profiles of zidovudine and stavudine were sufficiently different to transition a patient from one of these drugs to the other. Ditto certain nevirapine mutations and efavirenz. Not true!

The fact that our treatments failed in some of our most devoted and adherent patients resonated strongly with us HIV specialists. It was heartbreaking. Some had been hopeful volunteers in early clinical trials, which exposed them to inadequately dosed single-drugs that then led to a loss of this drug class. In hindsight, how ironic — and how tragic.

Others had to go through desperate (but ultimately failed) attempts to achieve viral suppression, including:

- “Mega-HAART” — using 6 or more drugs in untested combinations.

- “Double-boosted PIs” — two protease inhibitors with ritonavir.

- Hydroxyurea — raised intracellular concentrations of didanosine, with many untoward effects. Ugh, even writing that we prescribed that combination makes me cringe.

- Treatment interruptions in order to “resensitize” their virus to the drugs we did have — didn’t work, led to increased risk of disease progression.

The silver lining to this resistance was that the virus became less fit; the viral load rebounded, but there was a substantial delay before the CD4 cell count declined. Patients remained remarkably stable clinically even with viremia and resistance.

This disconnect between viral load rebound and CD4 decline allowed many to survive until the miracle year of 2008, when finally we had a potent new drug in a new drug class — raltegravir, the first integrase inhibitor, approved in 2007 — plus drugs from existing classes with activity against most resistant viruses, specifically darunavir (PI, approved in 2006) and etravirine (NNRTI, approved in 2008). (Maraviroc played a less important role, since most of these patients already had non-R5 virus.)

Why bring this up now? On the eve of the 2019 International AIDS Conference, which takes place this week in Mexico City, I think back to when the conference was here last — that magic year of 2008.

It was during that 2008 Mexico City meeting that we first saw data from the TRIO study (later published here, lead by Yazdan Yazdanpanah), which enrolled participants with resistance to NRTIs, NNRTIs, and PIs, and gave them all three of these new drugs — raltegravir, darunavir, and etravirine.

The results were staggeringly good — 91% had viral suppression at week 24, a rate quite comparable to responses in treatment-naive patients with no resistance. It was actually a bit better, reflecting the high level of adherence for these motivated participants. In HIV clinics around the world, this “TRIO” regimen became the default standard for treating multidrug-resistant HIV — and it worked just as well in clinical practice as it did in the clinical trial.

At last, we could effectively treat these brave people who had weathered years of viral failure, immunosuppression, and the toxicities of early antiretroviral therapy. Many experienced the joys of hearing they had an undetectable viral load for the very first time. Treatment failure with multi-class resistance became increasingly rare — so much so that a popular HIV drug resistance test stopped selling its product, the laboratory equivalent of closing an inpatient hospice for people with AIDS.

I’m happy to report that this wasn’t a brief honeymoon phase — responses were durable, and most people with multidrug-resistant HIV have had viral suppression since 2008. The reality is that in many parts of the world, the patient with “no treatment options” due to resistance has become an exceedingly rare occurrence.

Even busy practices and referral centers see very few of these cases; in the past two years, most have seen zero:

Hey HIV treaters out there–in the past 2 years, do you follow, or have you seen, any people with viral failure and resistance to ALL major HIV drug classes? (Enfuvirtide and ibalizumab excluded.) If yes, share how many in the replies. (I've seen 2.)

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 20, 2019

This is not to say that it never happens anymore — a paper published recently in Clinical Infectious Diseases enrolled 20 such individuals, admitting them to an NIH inpatient center for directly-observed therapy. Of note, in this group (which included several with perinatal HIV), nonadherence turned out to be the primary reason for failure in 9 of the 20.

So here’s to 2008, a year when our knottiest HIV-resistance problems became solvable — hooray! It was a tremendous advance, one underrated in my opinion when people retell the history of antiretroviral therapy.

And what we will learn this year in Mexico City? That will be next week’s post!

Speaking of drug resistance, here’s another take:

July 14th, 2019

The House of God Profiled Physician Burnout Long Before We Called It That — Should Aspiring Doctors Still Read It?

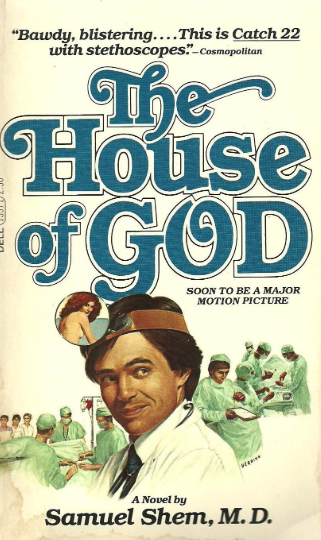

Many consider the novel The House of God, written by Samuel Shem (pen name for Stephen Bergman), to be a must-read for any physician or soon-to-be physician. A fictionalized account of his internship year, the book details how the accumulated stress, fatigue, and powerlessness of being a first-year doctor inexorably accumulates during that year — with sometimes hilarious, and but also disastrous, results.

The survival strategies of the interns in the book under such circumstances are not pretty. Cynicism becomes the default attitude, an us-versus-them camaraderie that considers the “them” to be not only hospital administrators and older staff physicians — but painfully, the patients, too.

Other survival tactics fall into the “instant gratification” category — the book is packed with sex, and drinking (but especially sex) — which no doubt boosted its readership, and also (warning) makes re-reading it today somewhat cringe-worthy, I imagine especially for women.

This insider look delivered by The House of God was at first widely criticized by the medical establishment. However, over time, the book has become a canonical and widely praised real-world depiction of internship — many doctors I know have read it, and it even appears in the humanistic curricula of some medical schools.

I first read the book in college, a time when I was seriously considering medical school. I found it funny, and surprising — could young doctors really be having so much sex? — but also quite sad (one of the characters takes his own life). And the grotesque depiction of the patients, especially the elderly and infirm, made me very uncomfortable, an undoubtedly intentional goal of the author to show how depersonalizing the whole experience had been.

Frankly, it filled me with dread about the prospects of becoming a doctor.

Re-reading it later, some years after my own training, I saw the extreme perspective as a necessary cry for help — these interns clearly manifested all the characteristics we now commonly refer to as physician burnout.

I could also appreciate the clinical insights embedded in the famous “Laws of the House of God”— #3 is absolutely brilliant:

3. At a cardiac arrest, the first procedure is to take your own pulse.

So my re-read found nuggets that included a human side to doctoring — The Fat Man character is clearly a great clinician — albeit these are few and far between. It’s no wonder that the online reader reviews of this book are so disparate, with plenty of angry one-star reviews mixed in with the general praise.

So why is it in the news now? And why bring it up here?

JAMA this week published a thoughtful perspective on The House of God, plus a piece by Bergman himself. It’s not just to mark the 40th anniversary of its publication; Bergman plans to release a sequel in November. Entitled Man’s 4th Best Hospital, the book will attack the current focus of healthcare on money, and screens, in particular electronic medical records, targets deserving of satire.

From a “pre-review” by WBUR’s Carey Goldberg:

But more than 40 years on, author Samuel Shem trains the satirical sights of his sequel on two particular targets: screens and money. And he connects them, pointing out that the electronic medical record systems that drive many doctors (and patients) crazy are really fundamentally billing systems pretending to be care systems.

With one of his ultra-simple syllogisms, the Fat Man sums it up:

MONEY KILLS CARE

SCREENS MAKE MONEY

SCREENS KILL CARE

Sounds like it will be another cry for help, this time to get us back to connecting with our patients — to pull us away from our electronic billing (I mean medical) records, and to care for them. I look forward to reading it!

As for why here, on an ID blog, regular readers might have gathered over the years that I have an interest in baseball.

(Hey, understatement sometimes is amusing.)

The House of God reminds me in many ways of another book from that era, the baseball classic Ball Four, another insider look at an extreme work environment — this time playing professional baseball. (And also, for the record, Kitchen Confidential. But that’s a different post.)

And last week, as JAMA released its pieces on The House of God, we baseball fans learned that the author of Ball Four, Jim Bouton, had died.

Just like The House of God, it also appeared in the 1970s, and was similarly widely criticized on release by the establishment — this time, the baseball establishment, who preferred a more white-washed, athlete-as-hero illusion of the players. But despite their protestations, the book was a huge critical success, and is now celebrated as a heartfelt and accurate account of what it’s like to live through the grind of a not-so-successful baseball season.

Also like The House of God, the book is very funny, and the players resort to plenty of sex and drinking (but especially drinking this time) — ways to overcome the stress of incessant performance demands, contract disputes, and relentless travel in a sport where management can dispassionately trade you to another team or drop you to the minor leagues for any decline in productivity.

But Ball Four differs from The House of God in two critical ways. First, it’s an autobiographical account, not fiction — these are real people, and it’s Bouton’s voice we hear telling the story.

Second, and more importantly, the joys of playing the game come through strongly. The many problems Bouton has on that 1969 Seattle Pilots team notwithstanding, he clearly loves baseball and deeply respects the hard-work and talent it takes to succeed at this professional level.

A much-quoted line from Ball Four captures this love perfectly:

A ballplayer spends a good piece of his life gripping a baseball, and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.

There’s nothing like this in The House of God — no joy from patient care, or their gratitude, or how rewarding it can be to master medical information over the course of residency, and then pay it back by teaching medical students and interns. Sure, there’s camaraderie in the book, but much of it is soured by the brutal experiences they are living through.

One of my colleagues has suggested that people wait until after they complete residency before reading the book.

I think he’s right.

What do you think?

July 7th, 2019

In Praise of Experienced ID Fellows — and a Dozen On-Service ID Learning Units

A few weeks ago, I cautioned ID fellows about underestimating their hospital’s interns and residents.

A few weeks ago, I cautioned ID fellows about underestimating their hospital’s interns and residents.

My message — you were like them not so long ago; they didn’t suddenly all lose their brainpower when you graduated. This ungenerous opinion of house staff may be especially held by experienced fellows, as the accumulating workload of the year can lead to impatience.

OK, grouchiness.

The post might have felt a bit tough on current fellows, but that was not my intention. As I noted at the start (citing my own experience), it’s nearly a universal illusion, one we all have to get through.

So here’s the flip side of working with those experienced ID fellows — for us attendings, it’s wonderful.

I frequently attend on the inpatient ID service during the transition period between fellowship years, and once again it’s been an absolute joy to witness the expertise and confidence of these seasoned pros as they finish their fellowship year.

Their clinical instincts. Their remarkable growth in fund of knowledge. Their ability to assess, rapidly, not just “sick” vs. “not sick” — that starts with residency — but even more importantly, “sick from an ID problem” vs. “sick from something else entirely; the ID issue is secondary.”

The skills go on. The experienced ID fellows focus their diagnostic and therapeutic suggestions in ways that would have been impossible for them just months ago. They handle serious, difficult ID problems — Staph aureus bacteremia, a new HIV diagnosis, epidural abscess — with confidence and aplomb. They communicate with patients, family members, and consulting teams accurately and clearly, without excessive jargon.

As they present cases on rounds, I await their assessments with deep interest — as more often than not they have insights about diagnosis and treatment that are spot-on.

Plus — and this is a tough one — they recognize that the late afternoon or weekend consult may be highly appropriate, and not just an annoyance, no matter how busy the day.

So thank you, ID fellows who have just finished their first year — it’s been a blast.

And here’s a list of some of what we discussed on rounds — a dozen “Learning Units” for each day on service:

Day #1: Transmitted HIV drug resistance mutations in newly diagnosed people with HIV often have no clinical significance (e.g., L90M in PI is most common). Latest data from @CDCgov not yet published but summarized in this valuable poster from #CROI2019. https://t.co/KcCR66RVuw … pic.twitter.com/BgcTHFyqRS

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 26, 2019

Day #2: @IDSAInfo guidelines recommend dilated ophtho. evals in all non-neutropenic pts w/ candidemia, but this widely cited recent review found the practice to be of questionable yield. Do you still recommend it? @FungalDoc @GermHunterMD @FranciscoMarty_ https://t.co/YvT6JpSFuN

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 27, 2019

Day #3: The @KariusDx DNA sequencing test may assist in dx for difficult to culture pathogens (as in this case report of C. burnetii endocarditis); broader role in clinical practice still to be determined by sensitivity, specificity, and cost. https://t.co/8FZfFGzqte

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 28, 2019

Day #4: Dropped gallstones as a nidus for abdominal abscess, sometimes with actinomyces; can also cause empyema. https://t.co/SmUqg7SWTp

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 29, 2019

Day #5: The "inoculum effect" is a main reason to favor oxacillin/nafcillin over cefazolin in serious infections due to MSSA. But how then to explain the numerous observational studies demonstrating comparable (or better) outcomes with cefazolin? https://t.co/MqqqQJENkR

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 30, 2019

Day #6: Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome should be considered in patients with rural exposure (esp southwest USA) and pulmonary interstitial edema on chest radiographs in association with leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, and hemoconcentration. https://t.co/4o5Vc855re

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 1, 2019

Day #7: In this retrospective series, 46 (38%) of 122 patients with pure aortic insufficiency requiring valve replacement had endocarditis. Study done in the pre-molecular diagnostics era — would it be different now? https://t.co/K5j1IHdYpN

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 2, 2019

Day #8: The risk of stroke is increased after herpes zoster, in particular within the first 3 months and after V1 HZ. Treat with acyclovir, though one wonders if this is beneficial in late-onset cases (where CSF PCR may be negative). https://t.co/TLGUxFdKtV

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 4, 2019

Day #9: The most common infectious causes of broncholithiasis are histoplasmosis and TB, but any granulomatous process can be responsible. Management highly variable depending on location and clinical symptoms. Good recent review: https://t.co/5No3zGLHQo

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 4, 2019

Day #10: P. acnes (now C. acnes) is an important cause of post-neurosurgical infection. Key points: 1) long duration of symptoms; 2) no fever; 3) nl wbc; 4) delayed presentation post surgery; 5) anaerobe, slow to grow. Good early case series: https://t.co/SYr5oWtGRR

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 5, 2019

Day #11: Despite some reports of resistance, doxycycline remains the treatment of choice for Mycoplasma hominis infection. Alternatives include quinolones and clindamycin. Azithromycin should be avoided. https://t.co/Of9DHpJVYe

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 6, 2019

Day #12. In a low TB prevalence setting (USA), a single negative Xpert MTB/RIF sputum test had a negative predictive value for TB of 99.7%; two tests 100%! This study has had a major impact on infection control policies in US hospitals. @ACTGNetwork https://t.co/cqNZFMn58B

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 7, 2019

And finally…

What an outstanding group. Much gratitude to you all! https://t.co/RO7MkUbV3Y

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 3, 2019

June 30th, 2019

Antibiotic Development Is Broken, Brothers in ID Practice, and This Year’s Winner of the ID-Related Social Media Award

I am currently rounding on the inpatient ID service, the new ID fellows arrive shortly, and Louie needs intensive doggy psychotherapy after yesterday’s strong thunderstorms here in Boston.

Busy times!

As a result, today’s post has no unifying theme. But what it lacks in cohesiveness it more than compensates in value, as here are three highly interesting ID-related items for your perusal.

1. Antibiotic development is broken — and how to fix it.

This fascinating perspective in the New England Journal of Medicine focuses on the problems with our current model of antibiotic drug development. Why are for-profit companies abandoning antibiotic research? If antibiotic resistance is such a problem, why isn’t this “market opportunity” giving us new and better antibiotics?

The absolute number of infections caused by each type of resistant bacterium is relatively small. Each newly approved antibiotic thus captures an ever-shrinking share of an increasingly splintered market — a problem that will only worsen over time. Short treatment durations and a coordinated program of antibiotic stewardship also contribute to low sales.

The authors’ proposed solution is to fund nonprofit organizations to develop antibiotics. Unlike private companies, they would not be beholden to shareholders to generate rapid profits. Relatively small revenues for a large private company — tens of millions of dollars annually — would, for a nonprofit, be a substantial win, and a chance to reinvest this money into further research.

Now they just have to convince some entity — government? philanthropy? — to invest the seed money to get this started.

A big hurdle, yes, but at least it’s a path forward.

2. Two brothers chat about being in ID practice — together.

For many academic ID fellowships, the intense first year of clinical care is followed by years of research training, with relatively little clinical work occasionally sprinkled in.

Research fellows might have a once-weekly half-day in clinic, or an occasional weekend seeing consults.

That’s the pathway Dr. Steve Threlkeld followed here in Boston when I first knew him as a brilliant ID fellow. (I was just starting my first faculty job.) However, he soon came to the realization that his true love was patient care, not research.

So he did something novel — he joined his brother Mike’s private ID practice in Memphis, Tennessee.

Steve and Mike chatted with me on this OFID podcast about private practice ID, what it has in common with academic ID and what’s different, how to be a blue-leaning clinician in a red-leaning state, and the unique opportunities and challenges of being the only sibling-owned private ID practice in the universe.

OK, someone contact me if I’m wrong about that last part.

Available also on iTunes, Overcast, and soon other podcast places.

3. This Year’s Winner of ID-Related Social Media Award.

I don’t know Dr. Philip Lee, but if there’s an Academy Award for ID content on social media, he’s the unequivocal 2019 winner — and we’re only halfway through the year.

Click on this Twitter thread for the incontrovertible proof:

Taylor Swift as antibiotics. A thread. pic.twitter.com/dY6We2VYkv

— Dr Philip Lee (@drphiliplee1) June 7, 2019

And fear not! One-a-Day ID Learning Units are coming soon.

June 23rd, 2019

Advice to Incoming Subspecialty Fellows — Don’t Underestimate or Belittle Your Interns and Residents

Around a million years ago, early during the first year of my ID fellowship, a medical intern consulted me about an elderly patient with a urinary tract infection.

Me: Does she have a catheter?

Intern: I don’t know.

Me: Has she been admitted before with a UTI? Any cultures?

Intern: I think so — wait, I’m not sure. Let me check her chart.

Me (testy): Nevermind — we’ll come by and see her. (Slams down phone.)

It might have been a busy day for me. Or a late afternoon consult. For whatever reason, I was feeling pretty fried.

Over the next week, I channeled my frustration with this exchange by citing it several times as an example of the general cluelessness of the current interns and residents — house staff at the very fine hospital that kindly had accepted me to their fellowship.

But wait. That can’t be right.

Indeed, let the record show that I was emphatically wrong — the interns and residents during my fellowship were outstanding. This particular intern had a PhD in immunology and was just getting started as a doctor. No surprise that not all the details were immediately at her fingertips.

I bring this up today because right now, in many teaching hospitals, the interns have already begun, and the subspecialty fellows are waiting in the wings. Most start in the next week or so.

It’s therefore a perfect time to take on this commonly held (and sometimes, alas, openly voiced) opinion by some subspecialty fellows as they grow into their new roles:

These interns and residents are weak!

There are numerous triggers to this ungenerous thought. Most involve consults deemed “inappropriate” by the subspecialty fellow, for a variety of reasons:

- Consult called without having complete information. (My example.)

- Consult called without asking the right question. (How can they always know the right question if they need help on a case?)

- Consult called “too early” in the admission, without the house staff doing the full initial work-up.

- Consult called “too late” in the admission, with the house staff mismanaging the case before calling the consult. (Look how the residents can’t win here, with both #3 and #4 suggesting some magical precise correct time for calling a consult.)

- Consult called too late in the day.

- Consult called by the medical student, which is deemed insulting to the newly minted fellow. (Oh come on.)

- Consult called for something the fellow would have handled without a consult when they were residents.

I bolded this last one since it’s probably the most common example. (Junior faculty sometimes succumb to this one as well. It’s an early form of, “In my day …”) What weakness!

So let me emphasize, again, by noting, emphatically, that this perception is a total illusion.

There is zero evidence that interns and residents are weaker, less thoughtful about patient care, and less thorough than we were during residency, whenever and wherever that may have been.

How do I know? Because there’s a control group — those who do their fellowships in the same hospital as their residency. These fellows sometimes cite weakness in residents who were, until very recently, their colleagues. And folks, it’s literally impossible that suddenly and unexpectedly, the entire house staff regressed, losing all their clinical skills when said fellow graduated.

So what’s behind this negative line of thought? And what can we do to correct it?

To answer these questions, a few months ago I posted the following:

Residents are never as good today as they were when we trained, and also never as good as hospital X than they are where we did our residency, wherever that might have been.

This isn't true, of course–so why are these views nearly universal? And what can we do about it?

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) April 20, 2019

Encouragingly, many responded that they feel that today’s house staff are wonderful.

But some acknowledged that the phenomenon exists, and offered various thoughts about its origins. I like this response, from ID colleague Dr. Andrej Spec (who may be better known on ID Twitter as @FungalDoc):

Nostalgia. That, and as we get better, it becomes easier to see the mistakes that we were oblivious to previously. The solution is to keep remembering the times we made mistakes. So that we put ourselves in perspective.

Or, from a rheumatologist (@Doctorkuch):

Thinking that everything you know now, you knew then (false!). #constantlylearning

These comments get right to the heart of the problem. We spend the years of residency honing our craft, becoming better at what we do through clinical experience, teaching conferences, and reading. By the time we are in our last year of residency, there’s a wonderful sense of mastery — that’s the good part.

The bad part is that we may unfairly expect similar mastery from our junior trainees.

So the next time we feel like criticizing an intern or resident for not having all the information, or not consulting at the right time, or calling a consult on a case we think we would have handled ourselves without a consult — remember what it was like to start your training.

And remember, this doctoring thing is hard — a lifelong exercise in learning, and trying to get better.

It may not be quite as difficult as getting this “smart” light bulb to work, but it’s close.

So how many ID docs does it take to change a light bulb?

June 16th, 2019

On Father’s Day, a Tribute to a Father Who Isn’t Allowed to Celebrate Father’s Day

Part 1. My Father and How I Became a Doctor

Part 1. My Father and How I Became a Doctor

I became a doctor with encouragement from my father.

Wait, let me rephrase that to capture what happened more accurately.

I became a doctor with a fair amount of pressure from my father.

Fresh off an adventure abroad, in my early 20s, I had all kinds of pretentious ambitions for my future.

Screenwriter. Comedy writer for a hit television series. Stand-up comedian. Fiction writer, periodically tossing off stories to The New Yorker while writing The Great American Novel.

Mind you, I had no idea how to make these aspirations actually happen. My writing output to that point included a few comedy pieces for the Harvard Lampoon (most of them in hindsight rather unfunny), and a piece in the Boston Phoenix (may it R.I.P.) describing my experience in a yogurt taste-test.

“Go to medical school,” said my father. “You can do anything once you have your degree.”

Absent an alternative plan — and trust me, there was no alternative plan — who was I to argue?

Spoiler alert — he was right.

Part 2. My Father, and How He Became a Doctor

My father comes from a family of doctors — and that’s understating it. His father, his uncle, his cousin, his brother — all doctors. His mother was a nurse, but probably would have been a doctor if Jewish women could go to medical school in Moscow in the early 20th century.

(His sister, my aunt, also married a doctor. In hindsight, what choice did she have?)

Medical pedigree notwithstanding, my father’s path to his MD was not easy. Skipped ahead twice in grade school because of his precocious reading skills, he entered college at age 15.

Unsurprisingly, he wasn’t ready for college life, and struggled socially and academically. Lonely, homesick, and with mediocre grades, he dreaded his own father’s visit during freshman year. Apparently, my grandfather didn’t take well to academic underperformance in his children.

But that visit never came. On the way to see my father in college, my grandparents were in a bad car accident. Both were severely injured, my grandfather didn’t survive.

It’s very hard to get inside the head of anyone, but imagine yourself at a university at age 15. You’re way too young, and already not doing well. And then this happens — your father dies, your mother injured. There are a million ways this story could go, most of them not good.

But my father’s response, amazingly, was to grow up — and to grow up fast. He doubled-down on his studies; he made friends. He applied to medical school — close to home so he could support his mother — and was accepted.

After residencies in both internal medicine and psychiatry, he became a practicing psychiatrist, and an esteemed teacher, jobs he truly loves.

I’ve always wondered if his college experience drove his choice of specialty, his desire to make something positive of the lessons learned enduring that trauma.

But that’s just the psychiatrist’s son speaking.

Part 3. My Father

Having married the unsentimental, smartest person in the world, my father can’t celebrate Father’s Day.

But I can do it for him, by listing here his best character traits:

Enthusiasm. The joke in my family is that my father will eat or drink something objectively mundane — a Ritz cracker, a glass of water — and stop conversation by saying, “This is the best water.” But the great thing about this enthusiasm is that it applies up and down the spectrum of experience, from those Ritz crackers and glasses of water to Chateau Latour, German expressionist art, 19th Century American literature, and tropical fish. (That last one ended badly, at least for the fish.) And as far as I’m concerned, we can’t have too many enthusiasts in the world — these are the people who brighten up the room when they enter.

A genuine interest in others. People invited to a dinner or other social event usually stick to the people they know, the familiar faces — it’s the easy route. But my father has always viewed the newcomers or strangers at these gatherings as fascinating sources of new life stories. He is deeply interested in others, and as a result is great company. And when you think about it for two seconds, it’s the perfect character trait for a psychiatrist. No wonder he loves his work, and is so good at it.

No detail is too small. There are “big picture” people out there who can’t be bothered with the small details. Then there are those who, on finding a topic they find interesting, can’t learn enough. My father is clearly in the latter camp, a voracious reader who delves deeply into a subject until he could practically write a PhD dissertation on it. You know that tower of books everyone has by their bedside? My father must be one of the few people on the planet actually to have read his entire stack.

This week's cover, “Bedtime Stories,” by Bruce Eric Kaplan. https://t.co/KXNilCUARs pic.twitter.com/S36UHATjzO

— The New Yorker (@NewYorker) June 3, 2019

Supportive of the people he loves. As I wrote last month, my mother went to graduate school and back to work when I was 11, leaving us three kids at home. (Sob again, but I’ve gotten over it.) In that Mad Men era, not all men would have supported this move, but my father did just the opposite — he became my mother’s biggest fan, constantly telling us and others how successful my mother had become. Let the record show he’s had the same attitude to all our personal and professional decisions — and in hindsight I believe he would have been fine had I not attended medical school, provided I was trying to do something.

So Happy Father’s Day, Dad! And I agree, those Ritz Crackers are great.

(Back to our usual Infectious Diseases programming next week.)

June 9th, 2019

Is It Safe to Alter the CCR5 Receptor? And How Will This Influence HIV Cure Studies?

The HIV cure effort suffered a potential setback this week, as researchers reported an association between having two copies of the CCR5-∆32 mutation and shorter survival.

The HIV cure effort suffered a potential setback this week, as researchers reported an association between having two copies of the CCR5-∆32 mutation and shorter survival.

(Quick reminder — the CCR5 receptor is required for most HIV strains to enter target cells. People homozygous for the CCR5-∆32 mutation are almost completely protected from contracting HIV.)

By evaluating over 400,000 individuals in a British registry that included genetic information including CCR5 status, the investigators compared the prevalence of CCR5-∆32 homozygosity among people between the ages of 41 and 76. Over time, the prevalence substantially declined, consistent with a 21% increase in all-cause mortality compared to those with either no ∆32 mutation, or heterozygotes.

The authors postulate that this excess mortality may be driven by the reported worse outcomes among those with ∆32 homozygosity who develop influenza or other infectious diseases. Since most influenza deaths occur in older people, this could explain why earlier studies of populations with ∆32 reported them to be healthy.

(By contrast, it might be that historical epidemic infections of childhood and young adults — smallpox, plague, dysentery among them — could have selected for ∆32 many centuries ago, with the result that approximately 10% of people of European heritage carry at least one mutation.)

As noted in the excellent editorial accompanying the new study, the findings should give researchers pause before making permanent changes to the host genome:

The most important point raised by the current publication is that considerable risk comes with generating mutations in the genome of human beings, no matter how obvious the benefit that those mutations offer.

I’d amplify this concern by noting that individuals born with two CCR5-∆32 mutations — who grow up with it — may differ from those in whom CCR5 is altered during adulthood. We simply don’t know whether people who acquire it late in life will be better or worse off than those born with the mutation.

So why is this recent study relevant to curing HIV? Considerable research has already been done on this receptor related to HIV cure:

- Only two people — the “Berlin” and the “London” patients — appear to have been cured of HIV. Both underwent stem cell (bone marrow) transplantation using donor cells harvested from people homozygous for the CCR5-∆32 mutation. The indications for the transplants were refractory leukemia and lymphoma for the Berlin and London patients, respectively. Both are off antiretroviral therapy with no viral rebound, and no virus detected either in blood or tissues.

- Zinc-finger nucleases successfully excised the CCR5 receptor from some cells of people with HIV. This small study (n=12) was a first step in trying to engineer something analogous to the Berlin and London patients without the risk of stem cell transplantation.

- A scientist reported that he used CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing to disable the CCR5 gene of two babies. The announcement was hugely controversial, as there was zero medical justification for this experiment on these children born to an HIV-negative mother. However, the cases underscore the feasibility of altering a person’s genome using the powerful tools available today.

- There is substantial ongoing research in coreceptor modification to prevent or cure HIV. In the linked review, it states “there are multiple clinical trials underway to evaluate how efficacious this therapy can be in human patients.”

Clinicians not actively caring for people with HIV might wonder whether the risks are worth it — isn’t HIV therapy now safe and all but 100% effective?

The reality is that there’s tremendous interest in HIV cure, especially among those with HIV, risks notwithstanding.

So great is this interest that many of us have even been asked by our patients whether they can have a bone marrow transplant:

Poll for people caring for those with HIV: Have you had a person with stable HIV ask if they could have a bone marrow transplant so that they can be cured, like the "Berlin Patient"? Thoughts about this? https://t.co/5ELxB6FFR7

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 8, 2019

That these questions mostly come from people doing quite well on their HIV therapy signals a powerful patient-driven motivation for HIV cure — one that sadly seems more related to ongoing HIV stigma than to the medical issues of current HIV treatment.

Which is why it’s not so clear that this latest research finding should dampen the pursuit of CCR5-driven cure strategies.

Would a lifetime 21% increase in all-cause mortality be an acceptable trade-off for a person with HIV who is deeply invested in HIV cure?

And who will get to decide?

June 2nd, 2019

A Highly Subjective Guide to Clinically Important Infections That Have Changed Names

Why do many clinically important microorganisms change names?

They haven’t married and taken their spouse’s name or gone to Hollywood and adopted a stage name.

Instead, through the tireless work of microbiologists, taxonomists, and geneticists, they have undergone sufficient reclassification so that their old name just doesn’t make sense anymore.

Or more graphically:

Why do clinical microbiologists love taxonomy? https://t.co/BdgGEUOFlh @ASMicrobiology #ASMClinMicro pic.twitter.com/fL3qgemYea

— JClinMicro EIC (@JClinMicro) May 17, 2019

What we gain in accuracy, alas, is accompanied by an increase in confusion, and a heavy taxation on our memory reserves. Even we ID types can barely keep the names straight; imagine how non-ID clinicians feel?

Our colleagues in clinical microbiology recognize this problem — really they do. But spend a little time reading Name Changes for Fungi of Medical Importance, and pretty soon you get deep into the weeds with no available machete to hack your way out. How’s this for an example?

The Ajellomycetaceae contains the teleomorph species Ajellomyces dermatitidis, Ajellomyces capsulatus, and Ajellomyces duboisii, the anamorphs of which are the genera Blastomyces and Histoplasma. The Ajellomycetaceae also contains some genera that have no known teleomorphs, including Paracoccidioides and the newly described genus Emergomyces.

Well, I’m sure glad we cleared that up!

So if you’re looking for an in-depth, detailed review of some recent name changes, take a look at the references section in this editorial, kindly sent to me by ID doctor and medical microbiologist Kim Henson. Warning — they are not for the faint of heart!

But here is a more subjective list of name changes that I’ve weathered over the years, along with a few miscellaneous comments:

Clostridium difficile became Clostridioides difficile. This recent change will take a while to get used to, as it’s such a common infection that Clostridium is pretty hardwired in our neural circuits. Also, the ubiquitous abbreviation “C. diff” still works fine, so there’s not much motivation to learn how to write, or to say, Clostridioides — in fact, I just had to teach my spell checker not to flag it.

Pneumocystis carinii became Pneumocystis jirovecii. It’s now quite clear that pneumocystis is a fungus (and not a protozoan, as originally thought). It’s also widely accepted (finally) that the species encountered in corticosteroid-treated rats is different from the one infecting humans — the rat gets Pneumocystis carinii, and humans Pneumocystis jirovecii. What’s still a matter of substantial debate is how to abbreviate the pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii, as demonstrated by this hotly-contested poll:

What's the current preferred abbreviation for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia? cc @UpToDate #IDtwitter https://t.co/uIq2dJEb1S

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) May 11, 2019

Haemophilus aphrophilus became Aggregatibacter aphrophilus. I attended a meeting a few years back which included several other ID geeks like myself, and we were discussing various aspects of our work. One mentioned she had just seen a case of endocarditis due to the wonderfully named Cardiobacterium hominis, which is of course the “C” in the HACEK group of organisms. I then mentioned that Haemophilus aphrophilus had been renamed Aggregatibacter aphrophilus — and suddenly there was a palpable sadness in the room. How could anyone be so heartless as to change the name of this whimsical and mellifluous-sounding microbe? Such a deep injustice, we’re still in mourning.

Streptococcus milleri became Streptococcus anginosus, intermedius, and constellatus. The name change to these abscess-forming streptococcal infections happened so long ago that many youngsters out there might not have even heard of Strep milleri. But trust me, it was tricky enough that for a while these three species were called “Strep milleri group” to help bridge the pain; now they’re called “Streptococcus anginosus group,” and milleri is no more. For the record, streptococcal taxonomy is mega-complicated and confusing — but if you think that is bad, wait until you start getting into the fungi!

Pseudallescheria boydii became Scedosporium boydii. Big improvement — Scedosporium is a wonderful word, replacing the strange and unspellable Pseudallescheria. I remember attending an ID conference during medical school that had two cases, both of which included details that caused me great confusion. The first was a streptococcal endocarditis case complicated by a “mycotic aneurysm.” Aren’t fungal infections called “mycoses”? So how did the strep cause a fungal complication — isn’t it a bacterial infection? (Turns out any infectious aneurysm is called “mycotic” — who knew?) The second was a post-traumatic fungal infection due to Pseudallescheria boydii, which I heard as “Pseudo …” which of course means “not genuine” or “sham” — you know, like “pseudo-intellectual.” So, if Pseudallescheria is the fake one, what’s the real one? I guess the real one is Scedosporium. Or not — fungal taxonomy is a total mess, right Andrej?

Just when you thought you understood Scetosporium. It gets more complicated, more difficult to treat, and like all of fungus, a taxonomic mess. #MSGERC2018 #MedEd pic.twitter.com/xZ7J0XABlv

— Andrej Spec, MD, MSCI (@FungalDoc) September 27, 2018

Propionibacterium acnes became Cutibacterium acnes. Of all the recent name changes, this is easily my favorite! I have already thoroughly embraced this new name, and even pedantically correct people stuck on the old one — making me excellent company on rounds. Maybe Cutibacterium will give greater attention to this under-appreciated pathogen, infamous for causing prosthetic joint (especially shoulder) and neurosurgical infections. And why do I like it? First, Propionibacterium is a devil to say, good riddance. Second, Cutibacterium is adorable, especially if you pronounce it “Cutie-bacterium.”

Xanthomonas maltophilia became Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. This problematic, highly antibiotic-resistant gram-negative rod changed names long ago — so as with Streptococcus milleri, many might not even have heard of Xanthomonas. I first learned about this bug when imipenem had just been FDA-approved (yes, I’m that old), as it is one of the rare gram negatives intrinsically resistant to carbapenems. Two other points worth emphasizing: 1) Xanthomonas sounds very cool, could almost be the name of a science fiction series, “The Galactic Empires of Xanthomonas”; 2) Stenotrophomonas is real mouthful. Takes a while to learn how to say that comfortably — which is why, to many cystic fibrosis clinicians and patients, it’s just known as “steno.”

Enterobacter aerogenes became Klebsiella aerogenes. C’mon, that’s just mean, flipping one enteric gram-negative rod name to another. I suppose we’ll get used to it eventually, grumble grumble.

Rochalimaea henselae became Bartonella henselae. These agents of cat scratch disease, endocarditis, bacillary angiomatosis, and peliosis hepatis haven’t been Rochalimaea for many years. But my friend Joel Gallant used to call my other friend Rochelle Walensky “Rochalimaea” long ago when they were at Johns Hopkins together — which just goes to show that we ID doctors have a very strange sense of humor, one that may be difficult to explain to others.

Diphyllobothrium latum became Dibothriocephalus latus. This fish tapeworm of gefilte fish fame wasn’t easy to learn in medical school, so I’m going to resist this change for as long as possible. Note that even CDC hasn’t updated their page, taxonomy notwithstanding, so I appear to be on safe ground holding out at least for now. Dibothriocephalus indeed, hmmph. Try saying that three times fast.

Penicillium marneffei became Talaromyces marneffei. This dimorphic fungus, endemic to Southeast Asia, causes disseminated disease in severely immunocompromised hosts. I always liked that we had a clinically important fungus that included the name Penicillium, reminding us of the source of our first beta lactam antibiotic. Oh well. This Talaromyces name is taking a while to get used to, probably because it’s not a common infection here.

Pseudomonas cepacia became Burkholderia cepacia. It hasn’t been Pseudomonas cepacia for ages. But did you know that Burkholderia cepacia is really at least two different species, Burkholderia multivorans and Burkholderia cenocepacia? Isn’t microbiology fun?

Streptococcus bovis became Streptococcus gallolyticus — and a whole host of other things. Medical school curricula indelibly impart certain ID facts to every student — three of them are 1) daptomycin is inactivated by lung surfactant; 2) listeria and its various dietary associations; and 3) endocarditis due to Streptococcus bovis should prompt a look for colon cancer. However, they haven’t yet gotten around to updating the species name, perhaps because hardly anyone remembers it. And did I mention that streptococcal taxonomy is confusing, irrational, and complicated? Sure I did, many times — and further reviewed the whole clinical world of clinical streptococcal infections here.

And last, but not least …

Ixodes dammini became Ixodes scapularis. Hey, no fair — I have enough trouble with microorganism taxonomy, do I have to start keeping track of insects arthropods too? All I know is that Gustave Dammin was an esteemed pathologist here at the Brigham for many years, and studied both Lyme Disease and babesiosis. Which begs the question — is it an honor, or a curse, to have such a nasty little critter named after you? Let the debate begin.

Any other name changes that deserve highlighting?

May 27th, 2019

A Day in the Life of a Malaria Diagnosis “Lab” — with Apologies to Twitter’s “Thoughts of Dog”

Scene: A quiet morning, somewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. A few roosters crow in the distance. A black Labrador Retriever slowly rouses herself from sleep.

Scene: A quiet morning, somewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. A few roosters crow in the distance. A black Labrador Retriever slowly rouses herself from sleep.

ah. nice long nighttime snoozle. my favorite thing. ending soon.

but many favorite things. partial list. i’m good with lists.

1. belly rub.

c. peanut butter.

4: stuffed toy lamb, with squeak. though missing ear now. because we played too much.

7. tennis ball left out in park. for weeks. better after warm rain. and other doggos chew.

g. last but should be first. you.

list could be longer. but hear sound of human. half open eyes. no one here yet.

back to snoozetown? not quite.

hear human sound again, coming down steps. now he’s on ground. with me. eye to eye.

nice pet behind ears. hmmm. but one ear left inside out. that’s ok. i forgive easy.

Who’s a good girl?

silly question. of course. i am. but he asks this a lot. so i tell him. i’m awesome.

awesome.

stretch legs. long yawn.

Time for work! Are you ready?

not work to me. my new favorite game. there are treats. simple rules. another list.

1. take socks from small humans.

(they smell delicious. especially socks of teenage boy humans. after playing football in African heat. yum.)

d. sniff socks of small humans.

7. some smell different. sad.

Work has shown that people infected with malaria parasites produce a body odour that is detected by mosquitoes, which results in malaria mosquitoes preferentially feeding on asymptomatic, malaria-infected individuals.

g. tell human which sock is sad. sometimes i just stay. sometimes bork.

5. best part. crunchy treat.

i could do this all day. especially if it helps small human. and if there are treats.

watch.

(Inspired by a recently published paper, a brilliant Twitter feed (“only” 2.6 million followers), and h/t Rich Davis for the clever pun in the title.)

May 19th, 2019

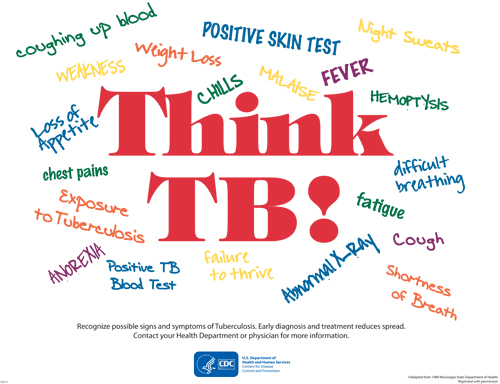

CDC Does Us a Huge Favor by Advising Against Annual Screening of Healthcare Workers for Latent TB

There are definitely things we do in medicine just because that’s how we’ve always done them.

There are definitely things we do in medicine just because that’s how we’ve always done them.

Among these evidence-free actions, we can include yearly screening for latent TB infection (LTBI) in all healthcare workers

If we carefully examine the rationale behind this practice — as this thorough review nicely does — one would be hard-pressed to find any other reason for this time- and labor-intensive annual flog.

Why does annual LTBI screening make no sense?

- Evidence from clinical studies that this strategy reduces TB incidence in US healthcare workers? Zero.

- Incidence of TB in the US over the past several decades? Steadily down, now at historic lows.

- Conversion of tuberculin skin tests (TSTs) or interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) among healthcare workers without an obvious TB exposure? Vanishingly rare.

- The testing is easy-to-do, highly accurate, and inexpensive? No to all.

Indeed, that’s why the new recommendation, from a joint effort by the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, is so welcome:

In the absence of known exposure or evidence of ongoing TB transmission, U.S. health care personnel … without LTBI should not undergo routine serial TB screening or testing at any interval after baseline (e.g., annually).

Extra points for clarity!

Encouragingly, all the ID and TB specialists I’ve queried lend their enthusiastic support to this change in policy. And this includes that extremely careful bunch who specialize in infection control.

Now we just need to turn this policy into action — which can start by dismantling serial testing requirements in hospitals and other healthcare facilities nationally.

Think what we can do with all that freed-up time!

Maybe even correct spelling errors on fax cover sheets.

"My name is Sax — that's spelled S-A-X, like the musical instrument."

Have been saying that for decades, so guess something like this fax cover sheet was bound to happen eventually. (With apologies to spell-checkers everywhere.) pic.twitter.com/3KMsJt7kO8— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) May 16, 2019