An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

January 24th, 2021

John Bartlett and Hank Aaron — Consistently Great for a Long, Long Time

Early last week, we lost one of the true giants in Infectious Diseases, Dr. John Bartlett. Long-time Chief of ID at Johns Hopkins, he was a true Infectious Diseases polymath — deeply knowledgeable about such a wide range of topics that virtually everyone in our field knew and respected him.

Early last week, we lost one of the true giants in Infectious Diseases, Dr. John Bartlett. Long-time Chief of ID at Johns Hopkins, he was a true Infectious Diseases polymath — deeply knowledgeable about such a wide range of topics that virtually everyone in our field knew and respected him.

If you’ll permit me to lift this from a previous tribute to John, here’s a partial list of his areas of expertise:

- HIV. Check.

- Clostridioides difficile. Check.

- Respiratory tract infections. Check.

- Antimicrobial resistance. Check.

- Anaerobic pulmonary infections. Check.

Given that breadth of knowledge, it’s no wonder that his annual summaries of “What’s Hot” in Infectious Diseases were must-see events at every IDSA/IDWeek meeting.

Year after year after year.

This consistency of greatness is no small feat. People get sidetracked. Or tired. Or motivated by greener pastures (money). Or hyper-focused on their own areas of expertise. As the famous quote goes, “An expert is one who knows more and more about less and less until he knows absolutely everything about nothing.”

John was the polar opposite of this kind of expert.

I’m convinced he maintained this broad view of our field because he was just such an innately curious and enthusiastic person. A (very) small example — I remember telling him of the surprisingly high treatment failure rates in people with high HIV viral loads with the two-drug combination of raltegravir and boosted darunavir in ACTG 5262.

“But they’re two of our best drugs,” he said to me in astonishment. (He was right about that.) “That’s absolutely fascinating! Why do you think that happened?”

For the record, we’re still not quite sure. But it did. And you can be sure that John was genuinely interested, immediately scribbling down a note about it on those ubiquitous yellow pads he carried with him everywhere.

Another remarkable quality of John’s was his extraordinary prescience, always knowing the next “big thing” in Infectious Diseases, often years before others. Here’s text from a paper he published — in 2008:

The United States needs to be better prepared for a large-scale medical catastrophe, be it a natural disaster, a bioterrorism act, or a pandemic. There are substantial planning efforts now devoted to responding to an influenza pandemic… Here, we identify some harsh realities: the US healthcare system is private, competitive, broke, and at capacity, so that any demand for surge cannot be met with existing economic resources, hospital beds, manpower, or supplies.

Chilling. Can you imagine how strong John’s voice would have been in our COVID-19 response had he been well enough this past year to participate?

John’s kindness and approachability, combined with his encyclopedic knowledge of all things ID, allowed him to teach, influence, and mentor countless medical students, residents, and fellows over the years. A distinguished chief of medicine (not an ID doctor) just told me she learned all her fundamental clinical ID knowledge from him during her residency at Hopkins. I have heard this same anecdote from numerous others.

Since everyone adored John, he used these relationships to gain insight from researchers and experts from all over the ID world. If someone started a clinical trial using a novel probiotic to prevent C. diff, he’d call that person and get the inside scoop (never disclosing non-public information, of course). Why this probiotic? What were the goals of the study? The challenges? What did they envision as the long-term risks and benefits?

“I wondered about why they chose this approach,” he’d say, “so I called Dr. — up, and here’s what he told me …” Hearing him talk about cutting edge ID clinical research was inside baseball at its best.

Speaking of baseball — this past week we also lost one of the greatest players who ever lived, Henry “Hank” Aaron, whose long and distinguished career strikes me as quite similar to John’s.

(Yes I can find baseball in anything.)

Aaron could hit for power, hit for average, throw, run, and field — a five-tool player, analogous to John Bartlett’s broad expertise. And it was sustained greatness, year after year after year. In baseball history, nobody was great for longer than Hank Aaron:

Nobody ever played the game so well, so consistently, so long. He was the wave crashing upon the shore.

That Aaron did this in the face of blistering racism, especially as he approached (and passed) Babe Ruth’s home run record, makes his achievements all the more impressive.

Two remarkable people — John Bartlett and Hank Aaron. What a week.

January 18th, 2021

COVID-19 Vaccine Frequently Asked Questions

In case you missed it, over on the New England Journal of Medicine, we now have a list of Covid-19 Frequently Asked Questions.

In case you missed it, over on the New England Journal of Medicine, we now have a list of Covid-19 Frequently Asked Questions.

(Why this NEJM Journal Watch site and the actual New England Journal of Medicine use different capitalization rules for this disease is a mystery. And don’t get me started on the Washington Post, which writes it as “covid-19”– all lower-case.)

It’s been a fun project to put these FAQs together, and my great hope is that it’s useful to clinicians and others who have questions about these amazing vaccines. Turns out I’ll learn a lot too.

So far, the single question that has drawn the most attention is this one:

Do the vaccines prevent transmission of the virus to others?

In my response, I try to highlight the fact that while we don’t have ironclad proof, it is highly likely that they will lower the risk. I urge you to read the full question where I outline the evidence so far.

In my response, however, I wrote this:

If there is an example of a vaccine in widespread clinical use that has this selective effect — prevents disease but not infection — I can’t think of one!

Some colleagues now have pointed out a few examples — diphtheria, meningitis B, and pertussis. My apologies for not mentioning these! We will update the site, and thanks for pointing this out.

Nonetheless, the general (if not ironclad) rule that vaccines typically reduce the risk of transmission to others remains true. After all, this is the primary reason why we have policies on mandatory school immunizations, influenza vaccines for hospital employees, and country-specific entry requirements for the yellow fever vaccine. Rubella immunization in particular is critical to prevent transmission of this otherwise benign infection to pregnant women. We also stress the importance of having immunizations up to date for people living with a person with a weakened immune system for this reason.

Sometimes it turns out to be an ancillary benefit of vaccine recommendations. This happened with expanded childhood immunization for pneumococcal disease, which has lowered the incidence in adults.Thanks, kids!

And it can be a great additional motivating factor for people considering the vaccine who might otherwise be undecided. Getting the shot protects you and protects others.

The challenge for us — as summarized in the New York Times — is communicating optimism about the vaccine’s high likelihood of reducing transmission, while at the same time acknowledging that we don’t yet know how much they’ll do so.

The overall message of the piece is that we’re “underselling” these vaccines. That the proven benefit of preventing severe disease is being undermined by caveats regarding disease transmission — about which we have limited, but promising, evidence.

(I suspect it will be a lot, though not 100% — but we’ll see.)

What to do practically in the meantime is also tricky, especially since the vaccine roll-out will be a process that takes months.

Here I totally agree with this piece’s well-stated conclusion, which I’ll quote in full.

We should immediately be more aggressive about mask-wearing and social distancing because of the new virus variants. We should vaccinate people as rapidly as possible — which will require approving other Covid vaccines when the data justifies it.

People who have received both of their vaccine shots, and have waited until they take effect, will be able to do things that unvaccinated people cannot — like having meals together and hugging their grandchildren. But until the pandemic is defeated, all Americans should wear masks in public, help unvaccinated people stay safe and contribute to a shared national project of saving every possible life.

Perfect! And looking forward to a time when the proportion of unvaccinated people is much smaller than it is today.

January 11th, 2021

After Ivermectin Controversy, A COVID-19-Free ID Link-o-Rama

Wow, quite the week for this country of ours. We’re all deeply saddened by the events, very hopeful that the transition in leadership will be peaceful.

And also an eventful week for this little blog. When I wrote “Enter ivermectin — and let the controversy begin,” little did I know.

Amazingly, this is already the second-most widely read post on this site over the past 365 days, and it’s been out less than a week. It’s closing in on number one, which came in early March — that’s when I not-so-boldly predicted we’d see a big increase in COVID-19 cases. Quite the visionary, wasn’t I?

(That was a rhetorical question.)

Anyway, who knew this obscure antiparasitic agent would capture so much attention?

With that controversy out of the way (ahem), allow me to return to non-COVID-19 ID/HIV for a brief time. I’ve been doing inpatient ID consults quite a bit recently, and here are a few of the interesting things that popped up:

- Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae is a nasty, nasty bug. In addition to liver abscesses, it frequently causes metastatic infection elsewhere, including septic arthritis, meningitis, and endophthalmitis.

- Nodular “granulomatous” pneumocystis pneumonia is an unusual radiographic presentation of PCP. Not all PCP presents with diffuse ground-glass infiltrates — and yes, I still abbreviate it PCP (PneumoCystis Pneumonia). Note that sputum induction and BAL may have lower sensitivity in granulomatous PCP, which will warrant other diagnostic strategies. For example …

- A markedly elevated beta-glucan in a person with HIV and respiratory symptoms is PCP until proven otherwise. Disseminated Talaromyces marneffei and histoplasmosis can also greatly increase beta-glucan in people with HIV, but PCP is way more common. (Should I change to saying PJP? It’s Pneumocystis Jirovecii Pneumonia, after all.)

- This is also true with non-HIV related immunosuppression, where a high beta-glucan and a compatible clinical syndrome are all but diagnostic. Many of the “false positive” beta-glucan results are not very high, or represent testing done in low pre-test probability settings. ID fellows will recognize that fact instantly! (Seems that switching to PJP is just a matter of time. Oh well. I’ll live.)

- Prior treatment failure of hepatitis B with lamivudine may induce entecavir cross-resistance. This is why it’s so critical that our heavily treatment-experienced patients with HIV/HBV receive tenofovir-based regimens — many received lamivudine for years before we knew about this issue of HBV cross-resistance.

- The preferred treatment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is TMP/SMX. Optimal dosing is unclear, though our crack ID pharmacy team recommend 12 mg/kg/day of the TMP component. (12? Not 10 or 15?) And yes, this is one of those fabulous ID tongue-twister bugs — one of the more common ones.

- TMP/SMX is probably as effective as pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine for CNS toxoplasmosis. Certainly it’s way less expensive (pyrimethamine, ouch), and much easier to take. It’s already standard of care in most of the rest of the world. Will our HIV opportunistic infection guidelines make this the case here in the USA as well? At least list it side-by-side with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, rather than listing it as an alternative?

- Intramedullary spinal cord abscess is a rare CNS infection that may be complicated by spinal artery occlusion. This review notes that 40% are cryptogenic, 20% come from a dermal sinus, and 20% from bacteremia. High incidence of permanent neurologic sequelae.

- Hair loss is a well-recognized complication of prolonged fluconazole use. Anecdotally I’ve seen this most commonly in those being treated for candida endocarditis, cryptococcal meningitis, and osteomyelitis. I’m sure it’s true for coccidioides, too, but we don’t see much of that in Boston. It slowly improves after stopping therapy, or decreasing the dose. In a similar theme …

- Blue skin is a well-recognized complication of prolonged minocycline use. Most cases do resolve over time after cessation of the drug, but sometimes it can be permanent. And it’s not just the skin — here’s a blue aorta!

- While UTIs in older adults no doubt are overdiagnosed (and overtreated), this paper hints that undertreatment may be a problem too. The problem is that assessing whether positive urine cultures are symptomatic — especially in older adults with cognitive impairment and multiple comorbidities — is an enormous challenge.

- Oral beta-lactam antibiotics might be a reasonable option for treating gram-negative bacteremia after all. The dogma has always been to use a fluoroquinolone or TMP/SMX. This study suggests beta-lactams may be a good option, provided it’s a urinary source and that initial treatment is parenteral.

- Penicillin-susceptible Staph aureus can be treated with penicillin — provided the microbiology laboratory confirms it’s truly sensitive. The critical thing is that the lab does this testing — some don’t. Anecdotally, penicillin is better tolerated than nafcillin and oxacillin, too.

- Should osteomyelitis complicating sacral pressure ulcers be treated with antibiotics? Generally no, argues this persuasive paper. And this question comes up all the time on inpatient ID services.

- Certain clinical and laboratory features are predictive of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) due to M. avium complex (MAC) in people with HIV. This contemporary series cites low body mass, low hemoglobin, and elevated alkaline phosphatase as readily available predictors. Note that the literature on management of HIV-related MAC IRIS is badly out of date. When should steroids be started? How long should they be continued? What are the side effects? A good project for a large cohort study.

Many thanks to ID fellows Drs. Susan Stanley, Alex Tatara, and Zach Nussbaum for providing some of these references. And remember all you fellows out there, you’re more than halfway done with your first year of fellowship!

For next week? Maybe I’ll write about albendazole. Or praziquantel. Or nitazoxanide. Or some other antiparasitic agent. They seem to be quite popular!

Or maybe I’ll just watch this baby bear playing on this golf green.

January 4th, 2021

Ivermectin for COVID-19 — Breakthrough Treatment or Hydroxychloroquine Redux?

It’s an indisputable fact that we need better treatments for COVID-19.

This is particularly true in the outpatient setting. Let’s count how many we have today, hmm, this shouldn’t take long. That would be zero — the same number we had over a year ago, when the disease first emerged in China.

Something safe, easy to take as a pill, and inexpensive. Something that isn’t a costly bioengineered molecule that requires lengthy infusions, given within a short time after diagnosis, to a highly contagious person.

Enter ivermectin — and let the controversy begin.

Yes, ivermectin — the drug licensed for use against strongyloides and other parasites, and probably best known to primary providers for its off-label use for scabies and head lice, and for pet owners as a common de-worming agent.

Of course upon hearing about this “repurposed” antiparasitic drug, many will develop a weary feeling of deja vu.

Didn’t we make this mistake with hydroxychloroquine? Wasn’t excess enthusiasm for this treatment a dismal chapter in our clinical and research approach to this new disease? Enthusiasm that led to wasteful, duplicative clinical trials, flawed observational studies, and irrational prescribing with arguably more harm than benefit? Harms that included not just side effects, but also drug shortages and pointless stockpiling?

Yes to all of the above.

Note that the harm done by the hydroxychloroquine controversy continues to this day. I know investigators who led well-done, fully powered clinical trials with negative results who were, and continue to be, viciously attacked in emails and on social media. Accusations typically charge that they succumbed to pressure from big pharma, or obscured favorable study results based on political agendas, or both.

Believe me, they wanted hydroxychloroquine to work. We all did! It’s relatively safe, inexpensive, widely available — but oh well, the clinical trials showed us it didn’t do much of anything.

Now — back to ivermectin. Where do we stand today? Unlike in the spring, when hydroxychloroquine use was rampant pretty much everywhere (and even appeared in some institutions’ treatment guidelines), this poll suggests that ivermectin use now is much more restrained:

Hey #IDTwitter and other clinicians who care for people with #COVID19. Have you prescribed (or recommended) ivermectin for this disease? Please vote and comment. Thank you!

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) January 3, 2021

However, there is a strong likelihood that the group voting on this little poll does not represent clinical practice globally. An article in October cited widespread use throughout Latin America, and many commenters to the above poll mentioned similar practices in their countries. Here’s a group of mostly South and Central American clinicians strongly advocating for ivermectin therapy for COVID-19.

Furthermore, many push for broader use of ivermectin in the U.S. as well. A group called the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance — made up of predominantly critical care clinicians — devotes much of its organization’s homepage to ivermectin’s promise for COVID-19 treatment, which they summarize in enthusiastic detail here.

Beyond these accounts, what else is out there?

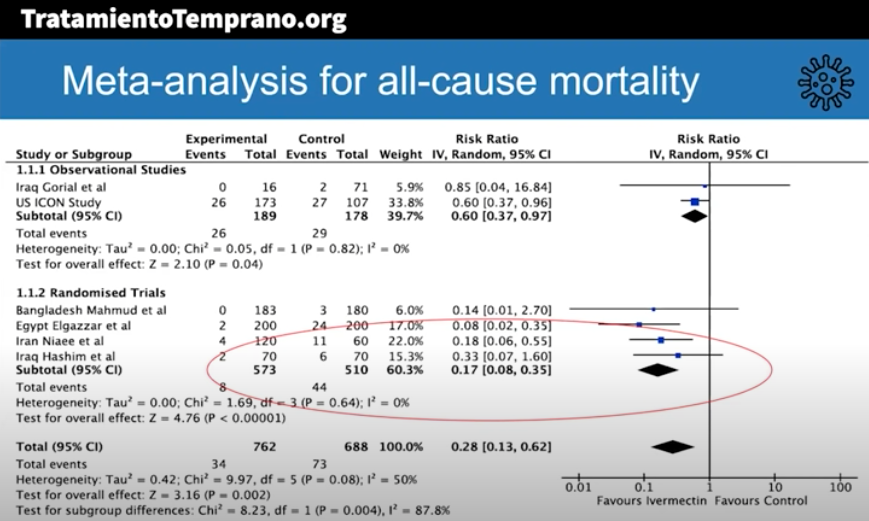

The best summary of the research evidence to date appeared recently in a presentation by Dr. Andrew Hill from the University of Liverpool. In a conference hosted by MedinCell, a company developing a long-acting ivermectin preparation, he presented the interim results of a meta-analysis funded by Unitaid.

Here are some key results (posted with permission):

The risk-ratio for mortality with ivermectin was 0.17 (95% confidence interval 0.08, 0.35), an 83% reduction in risk of dying. Outcomes for other endpoints (time to viral clearance, time to clinical recovery, duration of hospitalization) also favored treatment over controls.

Andrew was kind enough to speak with me today, mentioning that additional clinical trials will be included in the final meta-analysis, and that results are confirmatory. Some studies also included inflammatory markers such as D-dimer and IL-6, with favorable outcomes seen in these endpoints as well.

The presentation appropriately cites the limitations of the meta-analysis, which include the incompleteness of the data, that some of the studies were open label, and the difference in dosing regimens and endpoints. Also — critically important — publication bias may play a role, where we’re only privy to the studies that have what he calls the “good news.”

To further muddy the waters, “publication bias” is a generous term — none of these trials have yet been published in peer-reviewed journals.

Doubters will also understandably cite the very unimpressive pharmacokinetic (PK) data on ivermectin’s antiviral activity. Here’s our ID PharmD Jeff Pearson’s take:

I hope I’m wrong, but I don’t believe ivermectin will work for the treatment of COVID-19 for a variety of reasons (mostly being its PK, see here, here, and here).

But of course PK studies don’t always correlate with clinical activity, and ivermectin may have anti-inflammatory activity, as shown in this animal model.

My take-home view? The clinical trials data for ivermectin look stronger than they ever did for hydroxychloroquine, but we’re not quite yet at the “practice changing” level. Results from at least 5 randomized clinical trials are expected soon that might further inform the decision. NIH treatment guidelines still recommend against use of ivermectin for treatment of COVID-19, a recommendation I support pending further data — we shouldn’t have to wait long.

But we have to guard against two important biases here. First, that because we were burned by hydroxychloroquine means that all other repurposed antiparasitic drugs will fail too.

Second, that studies done in low- and middle-income countries must be discounted because, well, they weren’t done in the right places.

That’s not just bias, it’s also snobbery.

December 20th, 2020

With Vaccine Rollout, a Mixture of Gratitude, Envy, and Cautious Hope

Did I think we’d have two vaccines for COVID-19 available for distribution before 2021? Two vaccines with 95% efficacy in preventing disease, and nearly 100% in preventing severe disease? Vaccines that work across different patient populations, including the most vulnerable — especially older people?

Not a chance. I’ve probably been quoted half a dozen times saying that we likely wouldn’t be seeing vaccines before next year. Some “expert,” ha.

And yet, here we are. In this interview yesterday, you can clearly hear the excitement in my voice as I discuss the second emergency use authorization for the Moderna vaccine. Giddy.

Yes, it’s time to celebrate, to shed tears of joy when receiving the vaccine, to display happily the image of a bare biceps and the injection taking place, both vaccinator and vaccinated clearly smiling beneath the masks.

It’s even time to dance!

https://twitter.com/JournalsDance/status/1339875341628821506?s=20

II. Envy

Several friends and family members have asked — have you received your COVID-19 vaccine?

Answer: Not yet.

Can’t blame them for asking — I’m an ID doctor, after all, and finished a rotation of inpatient service just before Thanksgiving, and am about to start another over the the Christmas holidays. Most of us have been working solidly since March, no encampment to our country estates.

They might also ask after my wife, a primary care pediatrician who sees sniffly and coughing kids every day in her office practice, kids accompanied by their parents — many of them young adults at high risk for community acquisition of COVID-19.

Not yet for her, either.

The harsh reality is that there’s not yet enough vaccine to go around. Not even close.

In my hospital system, the overwhelming volume to sign-up for “Wave 1” of vaccine administration (of which I’m a part), initially caused the process to crash. It then reopened for approximately 15 minutes before the schedule filled. The supply is limited due to distribution issues beyond the hospital’s control.

Some did successfully sign up, but the first-come, first-served nature of the process allowed people to time their participation — you can be sure many set their phone alarms to go off at the precise moment the schedule came online again. Perhaps this process excluded those working the hardest, with the irony of this disconnect not lost on some.

But problems notwithstanding, I (and others in this first wave) likely will get the vaccine soon — I’m optimistic since with this second vaccine’s authorization, our hospital system’s supply should increase quickly.

My wife can’t be so certain. She and her partners own their practice, and their primary hospital does not have enough vaccines for affiliated primary care pediatricians or their staff.

Meanwhile, thousands of doctors (including several of our friends), nurses, respiratory therapists, and other frontline workers around the country have been vaccinated. Hooray! Plus, notably, some politicians blue and red — even Santa Claus.

Good for them. We’re happy for them.

But we’re envious, too. And if we feel this way, imagine how the broader public feels — those sequestered away the last 9 months, tired of the isolation, many older and at risk for severe COVID-19 and terrified. No accurate timeline for their vaccines. No wonder people are trying to jump the queue.

And yes, it’s hard to see those vaccine selfies, ouch.

https://twitter.com/DrSandman11/status/1339565524213182464?s=20

III. Cautious Hope

Hard to be hopeful right now. Cases continue to increase across the United States — now well more than 200,000 a day, with our country’s cumulative death toll over 300,000.

And unlike earlier surges, which targeted different regions at different times, this time it’s everywhere.

For the first time.

All red USA, now including Hawaii, for out of control covid.https://t.co/BpmBybV8U5 pic.twitter.com/Zyt8Uiaeq8— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) December 16, 2020

Public policies may be different from earlier surges — no extreme shutdowns — but that doesn’t mean things are safe, which is why so many caution against large holiday gatherings.

With these discouraging facts before us, how can we have any hope?

First, we have these two amazing vaccines cited above. An additional promising candidate — the Johnson & Johnson vaccine — has completed enrollment, with results expected in January. That vaccine requires only one dose and has way less stringent cold storage requirements. The AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine is on a similar timeline for availability, provided there are no further safety or efficacy setbacks.

Second, after months of logjams, rapid home testing for COVID-19 quietly advances. Two such tests have recently garnered approval — the Ellume and the BinaxNOW; others are in the works, and I increasingly hear people broadly supporting “flooding the market” with these tests. Here’s a letter sent to Congress summarizing why we need them, and how to get them approved and supported.

Because if people are going to get together — and they will — some testing is better than no testing, and lots of frequent testing is better yet.

Could we envision socializing safely with friends and family by the early spring, all of us recently vaccinated, and having a negative home test as a safeguard? And schools opening in the fall in ways that seem somewhat normal? Absolutely.

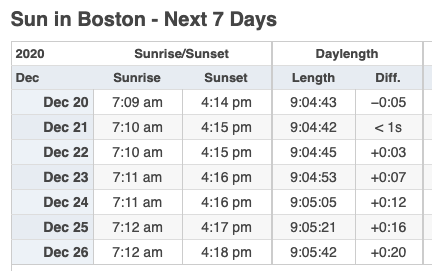

Third, starting early this week, the days start getting longer.

See, was that so hard?

December 13th, 2020

Brush with Greatness — Rochelle Walensky to Head CDC

There’s an overused expression that, despite its familiarity, really does describe some people perfectly. It’s when you say someone “lights up a room.”

My ID colleague and friend Dr. Rochelle Walensky certainly stands as a prime example. Right from the moment we first met during her interviews for ID fellowship in the late 1990s, I noticed Rochelle gave off this remarkable positive energy — a mix of enthusiasm, intelligence, and attentiveness that’s immediately obvious to all.

Here’s someone special, one inevitably thinks when meeting her. Here’s someone who listens and can get things done.

Of course, I write this soon after she’s been named the next head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a position she takes after 3 distinguished years as Chief of ID at Massachusetts General Hospital.

And while this move came as a surprise even to those who work closely with her — well played, Rochelle! — once the announcement became public, the response from the ID community has been nothing short of celebratory. I’m far from alone in holding this high opinion of her.

What can we expect from our new CDC director? If the track record from her work to date is any indication, let’s look forward to the following:

- Skillful analysis of data. She’s a highly accomplished researcher in disease modeling, having published nearly 300 papers, many quite influential, along with more in the popular press. And she loves numbers. CDC generates lots of numbers. She’ll most definitely fight COVID-19 with “science and facts.”

- Effective communication. A particular strength is her ability to convey complex information in a way that is understandable to people outside her field. Disease models may seem like the quintessential “black box” of computer spreadsheets and databases, but in Rochelle’s words, they are logical and clear.

- Generous leadership. A winner of several mentorship awards at Harvard, she will credit her team for their accomplishments. Don’t be surprised if we’re re-introduced to some spectacular talent at CDC — which will once again have a prominent voice. Welcome back!

- A focus on equity. Her colleague Dr. Robert Goldstein summed it up perfectly: “She approaches every part of her work understanding that, to do this well, we have to think about those that are most vulnerable and those that are most marginalized in our system.”

- A great doctor and a compassionate human being. When she was a first-year ID fellow, she was concerned about a young man from Africa who had been admitted with malaria and discharged home. Now, first-year ID fellows are incredibly busy; nonetheless, she took extra time in her clinic to see him in follow-up until he recovered.

Allow me to linger for a moment on this last one, the compassion piece. Rochelle made the extra effort to ensure her patient — new to this country, feverish from malaria, afraid — had good care. This is what good doctors, and good human beings, instinctively do. I have no doubt that had she chosen clinical care over research as her primary focus, she would have excelled in this domain as well.

And isn’t that human touch still so glaringly absent from our national response to the pandemic? Where’s the compassion? The appreciation for the sadness and sacrifice?

Rest assured, with Rochelle heading the CDC, that will soon be clearly evident, as she’s joining a distinguished group on the COVID-19 response known for their talent, character, and achievements.

Now, skeptics could read this post, and think, come on — nobody is this great. There must be something Dr. Rochelle Walensky doesn’t do well.

Ok, here it is.

She has lousy handwriting.

Nobody’s perfect.

December 6th, 2020

Getting Through a Grim, Dark Winter with Little Bits of Joy

The season’s first nor’easter came barreling through New England this weekend, bringing with it an added level of gloom to an already pretty grim time.

Grim because the virus sadly returned right on time, just like the other seasonal coronaviruses — and just like the virologists told us it would.

Short days, cold dark nights, wintry mix — never a fun trio. Add to that canceled vacations. Makeshift holiday “parties” that involve the computer. No hugs with extended family and friends.

And, worst of all, the rising toll of suffering, disability, and death, extending across our whole country. Ouch.

But — just as the world seemingly couldn’t get any darker, we now have a way out. With effective vaccines imminently available, there is genuine hope for putting this nasty virus in our rearview mirrors, or at least rendering it a minor nuisance. We just have to get through this winter first.

“We’re in the 7th inning”, said Dr. Michael Klompas, our hospital’s head of infection control, mobilizing a perfect metaphor — better than my rearview mirror one, so forgive me, Mike, for stealing it.

Every team gets 27 outs. Thanks to the tireless collaborative work of clinicians, scientists, researchers, public health officials, and study volunteers, the virus now has 18, and we (the home team) can take a slim lead with responsible behavior, broader access to testing, and widespread immunization.

Can we hunker down enough over the next few months to get the last 9 outs?

I’m proposing here that one key to getting through this winter is taking advantage of the little bits of joy that pop up periodically, reminding us that life goes on. Enjoying them. Being grateful for them. Sharing them.

It could be preparing a great meal with your family. Or, if you want to support your local restaurants, getting some special take-out, with a splurge on a bottle of wine. (Don’t forget the generous tip.)

Or take a wintry walk in the woods with a friend, all bundled up, taking advantage of the natural safety outdoor activities consistently give us when it comes to this pandemic life. Enjoy a properly distanced outdoor meal with another friend on an unseasonably warm day (they do happen) — have just discovered hot water bottles, they are miraculous!

Read that great but too-long book everyone has raved about for years. Middlemarch is particularly wonderful — doctoring and hospitals play a major role in the plot. If reading isn’t your thing, watch a serialized version of great literature — this Bleak House production is one of the very best things I’ve ever seen on television. Choose your favorite number 1 hit single. Or your least favorite, they’re just as fun. Enjoy some top 5-minute excerpts of Beethoven.

Random, little stuff too — here are a few more joy bits that came across my path this past week.

1. The brilliant cover to this week’s The New Yorker, with an extraordinary recreation. The talent and creativity of humankind never ceases to amaze. I’m particularly struck by the cocktail glasses — the color, fill, and tilt match so nicely!

https://twitter.com/nilknarfamme/status/1334158039360933888?s=20

2. My brother and sister-in-law’s new puppy, Zelda Fitzgerald. No further comment necessary.

3. How to make an AC/DC song in 30 seconds. Angus Young, the lead guitarist of the band, once said “I’m sick and tired of people saying that we put out 11 albums that sound exactly the same. In fact, we’ve put out 12 albums that sound exactly the same.”

4. Joe Posnanski’s latest baseball mega-project, the top 100 players not in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Encyclopedic knowledge of something is impressive enough; combining it with such great writing makes it truly special.

Who are the 100 greatest eligible players not in the Baseball Hall of Fame? @JPosnanski begins the countdown with an all-time hitter, a rookie phenom who inspired his own "mania" and a shooting star who streaked for five years ⤵️https://t.co/0RUV7BDQ5m

— The Athletic MLB (@TheAthleticMLB) November 30, 2020

5. Building a squirrel-proof bird feeder. It starts out as a war, but ends up as a triumph of human-squirrel collaboration and, amazingly, mutual appreciation — with some delightfully nerdy physics lessons thrown in as a bonus. Highly recommended.

Those are my joy bits. Anything you want to share?

Nine outs to go.

(H/T Susan Larrabee for the squirrel joy.)

November 29th, 2020

Great Questions from Our Course, Infectious Diseases in Primary Care — Plus Bonus Podcast

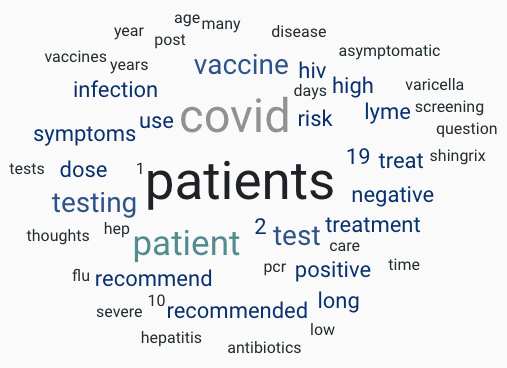

Going to take a partial break from all things COVID-19 today and recap some of the terrific questions we received in our course, Infectious Diseases in Primary Care.

Not surprisingly, there were plenty of COVID-19 questions but also the usual mix of practical queries from everyday practice.

Front-line clinicians doing office-based practice attend this course, and every year, they remind us of the common problems and quandaries they face in their day-to-day work. It’s a great mix of general internists, family practitioners, nurse practitioners, and PAs.

This year, of course, we held it virtually due to the pandemic, bringing with it predictable trade-offs.

On the plus side, more people could attend, the lectures are available to watch on-demand (at least for a while), and also the barrier to asking questions was lower — just type in a question and send!

On the other hand, we missed the personal interactions with participants and couldn’t get immediate feedback on whether what we were teaching was useful — watching people during teaching gives you a real sense of whether they’re with you on the topic or perplexed. Finally, humor during teaching is all but impossible to gauge — did the jokes land or fall flat?

But we got some amazing questions and didn’t have time to answer them all, so here’s a baker’s dozen and some quick answers.

Question #1: Would you give the recombinant zoster vaccine to someone who is 40 and at high risk because they are immunocompromised?

Answer: The quick answer is that the ACIP doesn’t yet recommend it in this population, but it has been studied in a variety of immunocompromised hosts (autologous stem cell transplants, rheumatoid arthritis), and it is safe and effective. So in general, the answer is don’t give it to people younger than 50, or to the severely immunosuppressed, at least for now; future guidelines may change, so stay tuned. (And of course, insurance may not cover it in this population.)

Question #2: Can you address the sensitivity/specificity of the rapid antigen tests for COVID-19 and the problem of low vs high pretest probability?

Answer: Since the antigen tests do not have an amplification step (unlike the PCR), they are less sensitive for detection of the virus. Despite this drawback, their rapid turnaround time makes them quite useful in certain settings. In a case where the pre-test probability is low — such as in an asymptomatic person with few or no high-risk exposures — a negative test further reduces the post-test probability that the person has asymptomatic COVID-19. Antigen tests are also quite likely to be positive in those who are most infectious.

By contrast, in a person who has compatible symptoms, a negative antigen test would not be sufficient to rule out the disease, especially in the hospital. Stick with PCR for those cases.

Question #3: What do I do when a job requires varicella titers, and they come back negative? The patients did receive their primary varicella vaccine series.

Answer: The varicella titers we do in clinical practice do not reliably assess for vaccine-induced immunity. Hence, we do not recommend them for this purpose, and the patient should provide proof of having had the primary series as sufficient evidence.

Question #4: Do we need to give a hepatitis B booster if it’s been a long time since the primary vaccine series? Someone recently told me he received it more than 30 years ago.

Answer: In general, boosters are not recommended after the hepatitis B vaccine series — especially if follow-up titers showed that at some point after the vaccine, the patient responded. (Checking is recommended for healthcare workers.) Even if the titer is now negative, exposure to hepatitis B will induce an anamnestic (always hard to pronounce!) response, so people will be protected.

One common exception to this rule is for people on hemodialysis. A repeat vaccine would be indicated if their titers all below 10 mIU/mL. Some people also recommend this strategy for other immunocompromised hosts, but this is not yet fully endorsed in guidelines. Here’s a great list of hepatitis B FAQs from the CDC.

Question #5: For fecal transplants, why do we not accept stool from obese donors?

Answer: There is evidence that the microbiome of normal versus overweight people differs and also that antibiotic administration (at least in childhood) leads to weight gain — remember, this is why livestock and poultry receive antibiotics, to fatten them up! Plus there’s at least one case report of emergent obesity after fecal transplant from an overweight donor. Unfortunately, we don’t have evidence yet of the converse — that normal-weight donors lead to weight loss in those who are overweight.

Question #6: Any evidence that vitamin D supplementation prevents or treats COVID-19?

Answer: Studies have shown that there is an association between low vitamin D levels and a higher risk of testing positive for COVID-19 and that people hospitalized with the disease have lower levels than population-based controls. One small, randomized trial also suggested a possible benefit of giving vitamin D.

While these data suggest that supplementation will help, remember that low vitamin D levels correlate with poor health in general and that the road is littered with failed studies of vitamin D treatment for a wide range of conditions, including critically ill people with respiratory failure. Pending the results of a fully powered study of vitamin D in COVID-19, we don’t currently recommend it.

Question #7: For our stable HIV patients, please specify which statins can be given safely with ART. (Note: I didn’t write “HAART”.)

Answer: It all depends whether the ART (and thank you for not saying “H—T”!) contains the pharmacokinetic boosters ritonavir or cobicistat, which can dangerously increase levels of certain statins, especially simvastatin. If not, especially if they’re on a dolutegravir- or bictegravir-containing regimen (as so many people with HIV are these days), then you can use any statin.

But if ritonavir or cobicistat is in the mix, go with low-dose atorvastatin (10-20 mg daily), as levels will increase 2-4 fold. Another alternative is pitavastatin — no interaction potential — though insurance sometimes doesn’t cover this one. Finally, efavirenz lowers atorvastatin levels somewhat, so starting with a slightly higher dose is reasonable. And if you’re not using the Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions site, start now!

Question #8: How should we dose trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for skin and soft tissue infections?

Answer: While a pivotal large clinical trial used two double-strength tablets twice daily, observational studies show no difference in outcomes between this and the standard 1 DS twice-daily approach. PharmD Bryan Hayes provides a nice summary of this controversy.

My practice is to recommend 2 DS twice daily for large and young people, and 1 DS twice daily for smaller and elderly patients — I’ll let you decide if this seems like a reasonable approach. And for the non-pediatricians out there, remember that each double-strength tablet contains 160 mg trimethoprim and 800 mg sulfamethoxazole — amazing how few clinicians of adults know that!

Question #9: It is my understanding that a tick must be attached for over 24 hours for a patient to get Lyme disease. Is that correct? Does this influence your approach to preventive therapy?

Answer: You are correct about the need for tick attachment for at least 24 hours before Lyme transmission, but the practical problem is that the ticks don’t provide us time-stamped receipts for how long they’ve been snacking on our blood. (So inconsiderate of them.)

So unless one has clear evidence about timing — went for a hike in the afternoon, tick found that evening — we tend to be quite liberal in our administration of preventive therapy, meaning that pretty much anyone who asks for it gets it. This goes against the guidelines, but it’s a much more real-world approach! Remember, too, that black-legged ticks are now ubiquitous in our region — one can pick them up doing pretty much any outdoor activity.

Question #10: If I treat someone for early Lyme, is there any reason to get a follow-up Lyme titer to confirm that my clinical diagnosis was correct?

Answer: Generally not — both because it won’t alter your approach to future therapy (people can get Lyme multiple times) and because there is some evidence that early antibiotic therapy blunts the antibody response to this infection. Some might argue that it’s good to have a baseline for future evaluations or to check based on curiosity alone, but neither reason in my opinion is sufficient to warrant doing the test. And yes, that’s two Lyme questions in a row — hey, this is New England!

Question #11: Corticosteroids used to be recommended for herpes zoster for prevention of the post-herpetic neuralgia. Can you comment on this?

Answer: While some older clinical trials suggested that steroids helped reduce pain in patients with acute herpes zoster, a Cochrane review of several randomized studies showed no aggregate benefit. A further limitation is that many of the studies excluded patients with even small contraindications to steroid treatment, such as having diabetes or being on immunosuppressive therapy. As a result, we ID docs don’t routinely recommend them — but the neurologists still sometimes do, and admittedly, a short course is unlikely to be harmful.

Question #12: What negative side effects of long term antibiotics do you educate patients about? (I have some on antibiotics for years from ‘Lyme specialists’.)

Answer: While the adverse effects of this strategy are well-documented (line infections, resistance, C. diff), it can sometimes be difficult to communicate this in a non-judgmental way. One sometimes useful strategy is to refer them either to the CDC site or, if they want something with a bit more narrative and without government associations, the Lyme Science site. The latter is a remarkable (and quite frightening) resource. Sorry, yet another Lyme question — there were so many!

Question #13: My patient had an illness consistent with COVID-19 in the spring but was never tested since there was such a shortage. Now he has prolonged post-illness fatigue and “brain fog” and wonders if he has “long COVID.” His antibody test is negative. Help!

Answer: This is a huge challenge on multiple fronts, as it’s possible he had COVID-19 in April but that his antibody titer has declined — it’s highly variable from person-to-person and also depends on what assay is being used. We unfortunately have no routine way to measure cellular immunity. Of course, it’s also possible he had a different viral respiratory tract infection.

Since I ended on this difficult topic of COVID-19 long-term symptoms, time to plug our latest podcast on Open Forum Infectious Diseases. Joining me is Dr. Vinay Prasad from UCSF, covering a wide range of COVID-19 issues, including treatments, research, long COVID, publications, and policies.

He has some remarkable (and controversial, no surprise) insights. You won’t regret it.

(Transcript here.)

November 24th, 2020

Some ID Things to Be Grateful for This Holiday Season — 2020 (!) Edition

“Grateful?” some might wonder. “He must be out of his mind.”

But even in the cursed year that began shortly after the first report of the disease now known as COVID-19 on (almost) New Year’s Eve, we can still find some things to praise, and to offer our gratitude. Or at the very least, acknowledge that without them, things would be so much worse.

Plus, it’s become an annual tradition on this site.

So here’s a list to get us started, just in time for Thanksgiving.

The remarkably high efficacy of experimental COVID-19 vaccines. These vaccines could have been a complete bust. Or like the flu vaccine, 40-50% effective in a good year, less than 20% in a bad one, usually worse than a coin-flip. Or accompanied by terrible side effects.

Instead, not only are the first two vaccines roughly 95% effective, but they prevent severe disease, including (by report) in the most vulnerable populations. No major side effects reported (yet). And they were developed with record-breaking speed, using a novel messenger RNA technology that is quite brilliant — even if it is totally obvious, ha ha.

love this

Nation Can’t Believe They Spent So Long Overlooking Obvious Solution Of mRNA Instructions For Spike Protein Encapsulated In Lipid Nanoparticle https://t.co/hi8kYHxhgb via @theonion h/t @_j_sax

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) November 20, 2020

Now reports show a third vaccine is effective even without this (so obvious) mRNA approach.

To the scientists who started working on these vaccines, to the labs and factories that put them together, to the companies that bet big on them, to the NIH for supporting the research, to the clinical research teams who enrolled tens of thousands of people working tirelessly for months, to the participants who volunteered — we owe our most heartfelt thank you.

The endurable scientific acumen and utter professionalism of Dr. Anthony Fauci. One of my patients, a no-nonsense guy in his late 40s who manages a car dealership, brought him up the other day out of the blue. “I love the guy,” he said. “He gives the medical information, doesn’t sugarcoat it, and doesn’t care about the political stuff.”

Exactly. We’ve all seen Tony (which is what everyone calls him) rise to the occasion during previous infectious threats, speaking about the science without reverting to hyperbole or pandering to his audience, but what he’s done with COVID-19 continues to amaze — he’s living what he describes as his “worst nightmare,” yet hardly misses a beat.

Even after retirement, people often referred to Joe DiMaggio as “The Greatest Living Ballplayer.” So do we have in Tony Fauci our Greatest Living ID Doctor? I think we do — though while he’s in great shape, he should work on improving his pitching.

The people who keep the hospitals running, but never get enough credit. I’m referring to the hard-working folks in food services, housekeeping, transport, engineering, security, phlebotomy, IT, laundry, admissions, and a whole slew of other jobs that make hospitals function — they are all coming to work each day, just like us clinicians, but (I’ll say it again):

They never get enough credit.

So here’s some credit — thank you so much!

The arrival of telemedicine (finally). In the Before Times, several barriers stopped telemedicine’s full adoption. But there was one big fat elephant in the room blocking the doorway, which was that most doctors would only get paid for face-to-face visits. It didn’t seem to matter that telemedicine could make patient care better and more convenient by improving access and limiting wasteful travel time.

And there were technological hurdles, too. While everyone else used fancy video calls and web conferencing that would make George Jetson jealous — Zoom existed before COVID-19, you know — most of us clinicians had to put up with systems that were buggy at best and didn’t work at all at their worst. And just try and coach a technophobe on how to download a proprietary secure app onto their cell phone, create a username and password, and log on.

Since COVID-19? Presto-Chango, telemedicine has very much arrived — so much so that for certain specialties (psychiatry, endocrinology, some primary care), virtual visits now can outnumber in-person appointments. One of my friends does all her routine surgical post-op checks virtually, only bringing patients in if there are problems or if her patients request to come in (most don’t). And most payers get it, and pay for it, at least for now.

Plus, the technology is much better. Zoom has come to patient care, and I’m also a huge fan of Doximity dialer.

Regulatory and payment issues remain (in particular providing virtual care across state lines), but telemedicine is too good and too important to allow it to go away, even after the pandemic is over. It’s here to stay.

Our remarkable hospital microbiology laboratories. These magnificent places have always held wonder for us ID doctors, providing both fascinating information about our cases and, in turn, making us look smart. Thank you for that!

But what they’ve done since early 2020 is nothing short of extraordinary. As everyone knows, test shortages for SARS-CoV-2 consistently hamper our country’s COVID-19 response. Even with this pressure, the microbiology labs have nonetheless pulled together enormous resources to make testing continually available in hospitals, and they have employed multiple redundant platforms to ensure that the system doesn’t break down

Oh yeah — they continue to do all that other stuff (stains, cultures, sensitivities, PCRs, MALDI, antigens, antibodies) we need for patient care. Amazing.

The meticulous and hard-working infection control practitioners. For non-ID readers, it may surprise you to hear that within the field of Infectious Diseases there is a group dedicated specifically to the field of infection control. They are key players in keeping us safe while working in the hospital; their reach extends to outpatient activities as well.

Not surprisingly, they are by nature drawn from a certain type of detail-oriented person. Here’s what I wrote a few years ago when discussing the “raging” controversy over whether doctors should wear white coats:

People who specialize in Infection Control are some of the most measured, data-driven, and methodical individuals in all of medicine. You know the stereotype of the brash, volatile, and cowboy surgeon, the person that everyone tiptoes around? These Infection Control folks are the polar opposite.

They also have a drive to get things right. During the pandemic, when many of us are working harder than ever, the specialists in infection control (mostly doctors and nurses) have simply not rested for months. I’m enormously grateful for all that they do.

Long-acting cabotegravir for HIV prevention. Had to get one non-COVID thing in here, and this was the easy choice. Daily TDF/FTC and TAF/FTC work great for pre-exposure prophylaxis, yes — but only if you take it. Plus, the data in women didn’t quite reach the high efficacy in men.

Which is why the results of HPTN 083 (men who have sex with men, transgender women) and HPTN 084 (at-risk women) are so exciting. In these studies, while TDF/FTC was effective, an injection of cabotegravir every 8 weeks was even better — so much so that both studies could be stopped early. Hooray! We are all looking forward to seeing more when these studies are published.

Honorable mention. There are bunch more things I could have mentioned, but this post has already gone on too long. Sorry!

So just briefly, here are a few, rapid-fire style — the ancillary bonus of how social distancing decreases influenza and other respiratory viral illnesses; the highly qualified people on the president-elect’s COVID-19 task force; the way the pandemic reinforced ID’s commitment to support health equity; the insightful voices of Zeynep Tufekci, Julia Marcus, Ed Yong, and certain other non-MDs in making us all think a bit deeper about what this all means; that more people can attend conferences since they went virtual; that most of us haven’t had to suffer an interminable airport delay since forever; that my favorite sports (tennis and baseball) are naturally socially distanced; that people rediscovered the great outdoors as the safest place to socialize; the Olive and Mabel competitions (“a bit of showboating, needs to be careful”); the poems America and Good Bones; and that this guy does the best The Crown impressions you’ll ever see.

https://youtu.be/-LQTBOBfA18

You get the idea. So what are you grateful for in late 2020? Don’t be shy.

November 18th, 2020

Just Another Urgent Plea from Your Friendly ID Doctor for Risk Mitigation as the Holiday Season Approaches

There’s lots in the press about how to have safe holiday gatherings in 2020 as cases of COVID-19 increase pretty much everywhere in this country.

How about this simple strategy?

Celebrate only with the people you live with already.

Bingo. That way Thanksgiving will be no riskier than your daily meals together.

End of advice column, right?

The problem is that this is analogous to advising abstinence for birth control or for prevention of sexually transmitted infections. It’s scientifically accurate, but the chances of 100% adherence by 100% of the population are zero.

So if we assume that this advice will not be followed by all — and that’s quite a fair assumption — how can we mitigate the risk?

Let’s make a list:

1. Keep the gathering small. Got a kid in college coming home for vacation? Sorry, the roommate can’t join the fun this year. No neighbors either.

2. Eat outside. Not so easy in New England, but as my hardy friend said, there’s no such thing as bad weather, just bad dressers. Plus the long-term forecast predicts warmth! Optimism!

3. Stay distanced if indoors. No, there’s nothing magic about 6 feet apart. But 6 feet is safer than 3 feet, and 9 feet is better than 6. You get the idea.

4. Wear masks while indoors and not eating. You do it now in public. You do it if someone comes to the house for a delivery or an appliance repair. Do it at home too if you have a visitor, even if it’s a family member.

5. Ventilation, ventilation, ventilation. This is for those who can’t eat outside. Open the windows. All of them. Here’s some more detailed advice from an expert, which most of us ID doctors emphatically are not:

I’ve seen a lot of questions about the importance of ventilation and the spread of SARS-CoV2. I have expertise in the science of indoor air quality & want to share some simple steps you can take to make your home & family safer during the pandemic. 1/

— Paula Olsiewski (@polsiewski) November 17, 2020

6. Keep the eating and drinking together time short. Risk of COVID-19 is a complex summation of distance, time, and activities during exposure to a person who’s infectious. And there’s hardly anything riskier than eating and talking together indoors — especially if the conversation becomes raucous, with people shouting.

7. In the week before the gathering, strictly limit social activities. Restaurants around the country are still open. Many places of worship are too. Time to start getting take-out food (tip well!), or joining your congregation electronically.

8. Give elders and otherwise vulnerable people an easy way to opt out. Even better, encourage them to join by zoom, facetime, google meets, or whatever platform is easiest for them. Study after study after study shows that this isn’t the same disease in everyone. Look at this figure — is there another infection that so shockingly discriminates by age?

The effect of age on the #COVID19 infection fatality rate. Just published @nature, data from 45 countries, 22 seroprevalence studies https://t.co/TWSogoHMMh

by @meganodris @hsalje @SCauchemez @fdlwang @datcummings @andrewazman and colleagues pic.twitter.com/pXtvZky4xA— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) November 2, 2020

9. Remember, it’s likely going to be weird like this for just one year. Got to love those vaccine study results — roughly 95% efficacy for two different vaccines! In a year’s time, let’s make getting your COVID-19 vaccine the ticket to gathering safely.

10. Get tested. Even better, get tested more than once, especially in the days leading up to the event.

Some might be surprised to read the advice about testing, which has gotten a bad name because it’s not fail-proof.

Am concerned that headlines like this (which are widespread) will discourage people from testing before seeing family. No, the tests aren't perfect, but they are *far* better than nothing. Get tested! Even if symptom-free! https://t.co/uBJ2O6rxeN

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) November 16, 2020

But this is not an all or nothing thing. Some testing is better than no testing. Remember, a negative test if done on a person without symptoms — even using less-sensitive antigen tests — lowers the likelihood that this person has contagious COVID-19.

It doesn’t replace the other strategies. But it does augment them.

Thank you for your time.