An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

April 11th, 2021

Poll: Will This Video Change Anyone’s Mind About Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine?

Watch this video. It’s a minute long:

I first heard about the video because, as mentioned before, I play in a regular poker game with a group of smart friends. Naturally, the in-person game, which started sometime in the early days of the 21th century, has been on hold since March of last year. One can barely imagine any activity more efficient for respiratory virus transmission than a bunch of people clustered around a small table, playing cards, chatting, eating snacks, and consuming beverages.

But we still play online, which one of our players estimates is approximately 64.7% as fun as the face-to-face game. So it’s quite appropriate that the video was sent around to all of us this past week after one of our online games. It came from Mo, a skillful player whose name sounds like it’s right out of a movie based on a tricky poker hustle.

I don’t think he expected this response from Mark (another poker expert) or me (a relative hack):

Mark: Just a big tech conspiracy.

Me: I can feel the microchip right under my biceps muscle.

Mo: Such cynics! Of course advertising by definition is supposed to manipulate you. But what’s wrong with being made to feel good about something good?

I agree this video is brilliant advertising and did make me feel good. It’s downright wonderful. The stark simplicity (always an enticing strength of a Google search), the music, the sound effects, the use of different languages, and, most importantly, the broad range of activities put on hold now possible again with vaccination — they all work together to convey a powerful and moving message.

No wonder some of the YouTube commenters wrote that they cried while watching it.

But will it convince anyone to get the vaccine who is otherwise not doing so?

Not so sure about that, but suspect not many. Why?

Our vaccine-eligible population, at least here in the United States, falls into various groups:

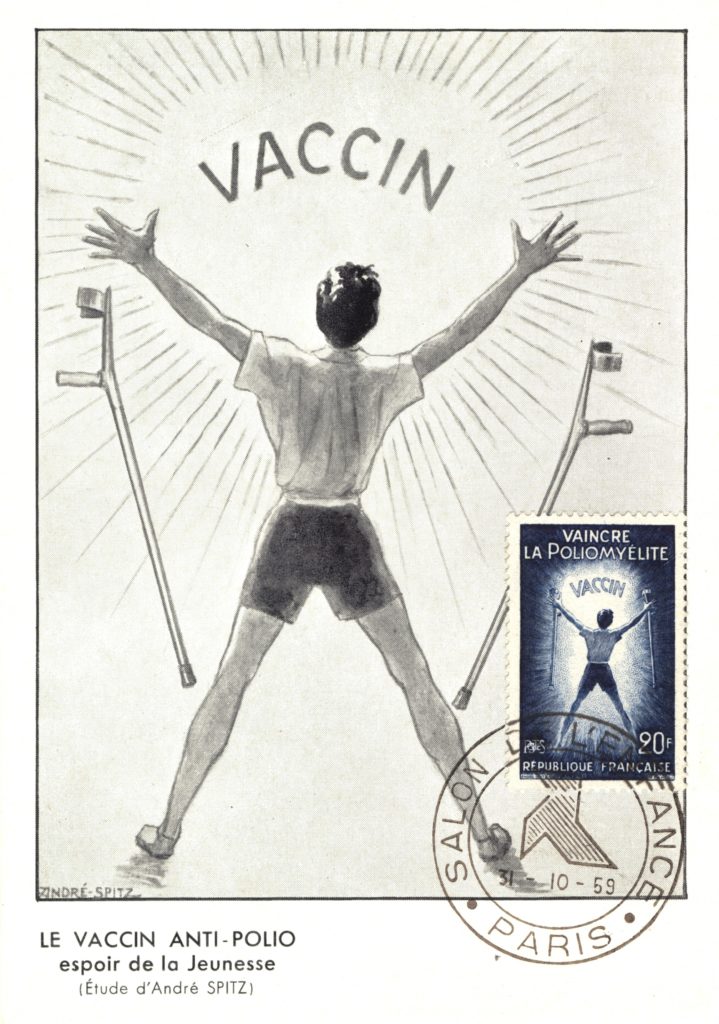

National Library of Congress

1. Most want the vaccine. They can’t wait. They signed up the very first day they were eligible. Or drove long distances to find a pharmacy that had extra shots. They watched the vaccine criteria in their states closely, hoping they and their loved ones would be candidates. Before then, they dropped in at end of the day at vaccination sites, eager for leftovers. When finally getting the vaccine, they were overwhelmed with emotion, gratitude, and relief. Maybe they took a vaccine selfie. Then they helped others navigate the process.

In short, this group loves this one-minute video. (So did all the poker players, for the record — including Mark.)

2. Some are on the fence because of a medical reason. They worry the vaccines are too new. That they might make their underlying autoimmune disease worse. Or they have a history of terrifying, life-threatening allergies to medications and maybe even vaccines. Or they are pregnant, or planning pregnancy. Or they had a rare, very severe side effect in the past to another vaccine, and worry these will do the same.

(All us ID doctors have been asked about people with Guillain-Barre syndrome after a flu shot and whether they can safely receive a COVID-19 vaccine. We say it’s safe — at least as far as we know.)

These are all legitimate concerns, for which there are no easy answers. People in this group might find the video well done, but it’s unlikely to alter their decision-making.

3. Some won’t get the vaccine since they come from marginalized groups. They might know about how the medical community excluded them from research in the past. Or conducted unethical studies. Or treated them poorly in a clinical context, so they inherently distrust our messages. Or they don’t speak English, and no culturally appropriate vaccine information is available. Or they have limited access to regular medical care.

I suspect this group won’t even see this video — where is it being distributed? — or if they do, they will distrust it.

4. Some await herd immunity, so they believe if they wait long enough, they won’t need to get the vaccine — ever. They are analogous to the parents who seek out “non-medical exemptions” for their children so that their kids won’t have to get the recommended childhood immunizations.

This group — particularly selfish, I should add — will watch this video and hope that it will convince others to get the shots.

5. Some are anti-vaxxers, or conspiracy theorists, or political extremists, or some combination of these factors. They will see in this video various hidden messages proving that the vaccines allow 5G mobile networks to take over their brainwaves.

I look at these five groups, and wonder — is this video going to sway anyone from Groups 2-5?

Will it, as cleverly put by Tom — another poker mate — “move the needle?”

What do you think? And why?

April 4th, 2021

More Excellent News on COVID-19 Vaccines — and Baseball Gets a Policy Right

A Joyful Easter, 1900. New York Public Library.

Big announcement this week from CDC, saying that people who have been fully vaccinated for COVID-19 can safely travel.

Of course many didn’t need this permission, as data increasingly show the vaccines not only powerfully protect you, but protect others. But having official endorsement from our cautious federal health agency surely means the data are especially strong.

For the record, it’s worth highlighting two recent bits of extremely good news on the vaccine front:

- The Pfizer vaccine continued to provide high-level protection at least 6 months after immunization. Over 90% effective in preventing any symptomatic disease, and 100% in preventing severe disease. Why is this important? The clinical trial started during the summer of 2020, which means these data take us through the winter surge in cases that occurred globally. Furthermore, the vaccine was just as effective in South Africa, where the more transmissible B.1.351 variant is highly prevalent.

- Prospectively collected data from the CDC show that people who received the mRNA vaccines were 90% less likely to get infected. The study included nearly 4000 front-line workers who were tested regularly by RT-PCR, even without symptoms, and confirms similar data collected in the United Kingdom and Israel, also with large sample sizes. Here’s why these data are important — fewer people with infection means fewer who can infect somebody else:

Amazing prospective @CDC data reinforcing that these vaccines prevent disease *and* infection — and hence reduce the risk of transmission.

Remember, fewer people with infection means fewer who can infect somebody else.

Let's get vaccinated ASAP! https://t.co/k9wl9Tsrmp

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) March 29, 2021

Many (including me) have always thought that it would be highly unusual if these powerfully effective vaccines failed to reduce transmission risk — now we have multiple lines of evidence that indeed they do. It may not be 100% — nothing is — but it’s a lot. To quote Dr. Neil Stone, “it takes a special kind of pessimist to believe that Covid vaccines won’t significantly reduce transmission of virus.”

We don’t want to be that kind of pessimist.

Why should we stress the highly favorable nature of the vaccine effectiveness data, both for personal health and the health of others? This will help many of those who are on the fence about whether to get vaccinated make the right decision — which is emphatically to get a COVID-19 vaccine. This will become increasingly important when supply of the vaccines exceeds the demand, and any adult will be eligible for immunization.

But what if this isn’t enough? Should we proceed with vaccine mandates in certain settings? Especially in high-risk transmission jobs, such as healthcare, where vaccination will both protect our patients and make the work environment safer for others working in the same setting?

As noted in this excellent concise review entitled “Should healthcare institutions mandate SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for staff?”, the question raises several challenging ethical questions. The piece covers the pros and cons, ultimately concluding that “mandates may be ethically permissible in select circumstances.” It also notes that from a practical perspective today, the current “emergency use authorization” of the vaccines makes them technically still experimental, hence a mandatory immunization is “legally and ethically problematic.”

I would argue, however, that with the pandemic still very much ongoing — COVID-19 cases are up substantially over the past few weeks — individual company policies can strongly encourage vaccination by making it the ticket to greater on-the-job benefits, flexibility, and freedom.

A carrot, not a stick.

An example? Here’s what Major League Baseball did, in a move this ID doctor and rabid baseball fan 100% supports:

Major League Baseball is getting back to normal. Players can now travel with their families. They can go to restaurants. They can play cards and move around on planes and buses. They can use whirlpools and saunas in the clubhouse. And they no longer are required to wear a mask on the bench or in the bullpen. However, teams are first required to have at least 85% of their players and staff fully vaccinated … Plus, these new protocols only apply to those who have been fully vaccinated.

In other words, if you and enough of your teammates agree to get vaccinated, here’s what you get in return — freedom! It’s analogous to CDC saying that fully vaccinated people can safely travel.

Despite the increase in cases, the pathway out of the pandemic looks brighter all the time. And it’s these amazing vaccines that will lead us there.

Spread the word.

March 21st, 2021

If You Want Thoughtful and Accurate Predictions About COVID-19, Zeynep Tufekci Has the Answers

Pufferfish, from United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842)

The future ain’t what it used to be, said one very wise man.

He might have also said, It’s difficult to make predictions, especially about the future, but alas we’ll have to credit that profundity to someone else.

Still, both these statements embody the insurmountable difficulty of making accurate predictions — a problem starkly evident during pandemic times. How many times have we watched people give conflicting views of when, or how, this thing is going to play out, even in the short term?

Two recent examples come to mind. Dr. Mike Osterholm, Director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, repeatedly warns of an additional surge this spring as more contagious variants take hold. This headline calls him “Dr Doom.”

On the flip side, Dr. Marty Makary from Johns Hopkins wrote in mid-February that we’ll likely be mostly done with COVID-19 in April — which, if I’m doing the math, starts 11 days from now. They can’t both be right.

Our ability to make accurate predictions is highly flawed, dependent on innumerable forces we can only begin to understand.

We base these predictions on our background, our education, our knowledge base, plus an unconscious force that sends them in various directions — optimistic or pessimistic, confident or timid, contrary or mainstream.

The bold ones get the most attention, especially if backed by impressive credentials. If Larry Summers says we’re heading into ruinous economic territory with the stimulus package, who am I to question him? Or Janet Yellen, who predicts the exact opposite?

Enter Zeynep Tufekci — sociologist, computer programmer, and Associate Professor at University of North Carolina. You might expect an epidemiologist, or infectious diseases specialist, or virologist to have the best record in laying out the most likely way forward as COVID-19 continues its march around the globe, now 15 months in. But again and again I have found hers to be among the most logical voices, mostly in pieces published in The Atlantic and The New York Times.

And importantly, I’m far from the only one to hold this view.

Is it her diverse educational and vocational background? The fact that she’s a true “citizen of the world,” having lived in multiple places? That she works really, really hard to get things right? That’s she’s also wicked smart, to coin the Bostonian phrase to describe the smartest person in the room?

Probably all of the above.

Zeynep kindly joined me recently on this Open Forum Infectious Diseases podcast to discuss how she ended up in her interesting current position, and her approach to COVID-19 — how we missed the mark for well over a month on the seriousness of the problem, our missteps on masks, the continued penchant for “beach scolding,” how we undersell the vaccines, and the general timidity of the biomedical community in questioning authority.

And yes, she finishes by speculating how this might end.

Highly recommended.

Transcript here. Also available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, etc.

March 14th, 2021

Really Rapid Review — CROI 2021 Virtual

For a few years in the early 2010s, the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) — in my opinion our premiere HIV scientific meeting — covered almost as many hepatitis C clinical trials as those on HIV. Or at least it seemed that way.

For a few years in the early 2010s, the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) — in my opinion our premiere HIV scientific meeting — covered almost as many hepatitis C clinical trials as those on HIV. Or at least it seemed that way.

This made sense at the time — the startling success of non-interferon-based HCV treatments made for exciting news, and rapid progress. Here’s what I wrote in 2013 in another patented, copyrighted, and trademarked CROI Really Rapid Review™, for which NEJM Journal Watch receives many millions of dollars in royalties:

The results of the sofosbuvir and ledipasvir study — 100% response in both naives and prior null responders — provided one of the more exciting clinical trial results I’ve seen in years, small sample size notwithstanding.

Remember those days? Well, this CROI had barely any HCV at all, a sign of progress.

(And I was kidding about the royalties, in case you were wondering.)

Of course, in 2021 we are in the midst of a pandemic, so it’s not surprising that this CROI had plenty of COVID-19 studies, both on COVID-19 alone and on the combination of HIV and COVID-19. Here are some highlights, starting with HIV, then the HIV/COVID-19 studies, and then some interesting COVID-19 alone papers.

The links are to the presented abstracts, which requires a conference account (at least it does today) — however, as with other HIV meetings, plenty of the presented material appears on the invaluable NATAP page.

- In the NADIA study, second-line therapy with dolutegravir was non-inferior to darunavir-ritonavir, and tenofovir/FTC non-inferior to ZDV/3TC. This beautifully done randomized clinical trial included patients with extensive NRTI resistance — lots of K65R plus M184V. Though conducted in Africa, it has lessons for us all, including: 1) residual activity of NRTIs even with high-level resistance; 2) imprecision of consensus interpretations of genotype tests, 3) no need for ZDV in those with K65R (phew), and 4) the need to monitor for INSTI resistance — even though it’s rare (just 4 cases out of 235 randomized to DTG), it has major clinical implications.

- In a large, US-based clinical cohort of people with advanced HIV disease, BIC/FTC/TAF was the three-drug regimen least likely to be discontinued. Also, a higher proportion had viral suppression than on boosted darunavir. These two strategies are being directly compared in the ongoing LAPTOP study in this very population. Speaking of people with advanced HIV disease …

- A cohort of 912 patients starting ART with various regimens favored initial integrase-based treatment over regimens with NNRTIs or PIs. Benefits were lower discontinuation rates and mortality. And more on this population …

- In a small (n=101) randomized trial in people with CD4 < 100, ABC/3TC/DTG had fewer drug discontinuations than ABC/3TC plus darunavir/ritonavir. Bacterial translocation was also lower with the DTG-based regimen. Note that higher rates of discontinuation of PI-based regimens have been observed before in patients with advanced disease. Speaking of this DTG versus DRV comparison …

- In an open-label randomized trial (n=306) in treatment-naive patients, DRV/c/FTC/TAF did not meet non-inferiority versus ABC/3TC/DTG. In other words, it was not noninferior — now you can show off to your statistician friends by using that double-negative language. Notably, weight gain was a bit more with DRV than DTG. (Shrugs.)

- In treatment-naive studies of BIC/FTC/TAF and DTG plus either TAF/FTC or ABC/3TC, viral suppression was still very high, even with transmitted drug resistance. The investigators used retrospective baseline next-generation sequencing of PR, RT, and integrase, with a 15% cutoff. Importantly, pre-study standard genotyping that identified resistance to the NRTIs was exclusionary.

- Injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine given every 8 weeks remains non-inferior to injections every 4 weeks at week 96. The current approval in the U.S. is for the 4-week strategy; approval of the 8-week approach is expected soon.

- For those switching to DTG/3TC, having M184V detected more recently increased the risk of virologic failure. This was compared to those with no historical M184V, and those in whom it had been found more than 5 years previously. Of course, this begs the question — why switch to DTG/3TC with a known M184V? Despite the ongoing activity of 3TC, this is not how the DTG/3TC regimen was studied. I wouldn’t do it.

- In a clinical cohort, predictors of 10% or more weight gain after switching to integrase-based ART were being female, underweight/normal weight, prior non-INSTI treatment, and the TDF to TAF switch. There was no difference between different INSTIs, however.

- Integrase-based ART was associated with an excess risk of cardiovascular events — but only after the first 6 months of exposure. It’s an observational study, so we cannot determine causality (just as we couldn’t with the first abacavir CVD study). And how do we explain that the effect was only temporary?

- In a database analysis of over 34,000 people starting or switching to integrase-based ART, new-onset diabetes or hyperglycemia occurred in 2.5%. This was significantly higher than non-integrase-based ART, with dolutegravir carrying the highest risk. Bictegravir was not included (database stopped in 2018), and there was very little TAF use.

- For pregnant women starting ART during pregnancy, DTG + TAF/FTC, DTG + TDF/FTC, and EFV/TDF/FTC had comparable viral suppression at 50 weeks’ postpartum. Pregnancy outcomes favored the TAF arm of the study — will our guidelines be updated soon based on this trial?

- In that study, the women in the DTG + TAF/FTC arm gained the most weight. However, this weight gain was closest to the recommended weight gain during pregnancy and also associated with a lower risk for any adverse pregnancy outcome, suggesting that pregnant women treated with EFV/TDF/FTC don’t gain enough weight.

- When started late in pregnancy, dolutegravir achieved viral suppression more rapidly than EFV. In this randomized trial of 237 women, there were three in utero HIV transmissions in the DTG arm, and one post-partum transmission in the EFV arm.

- A 4-month daily regimen of rifapentine and moxifloxacin was noninferior to the standard 6-month regimen for tuberculosis treatment. The participants also received isoniazid and pyrazinamide for the first 8 weeks. Anything that shortens TB treatment is a real advance!

- In highly treatment-experienced patients, oral lenacapavir induced a 1.93 log viral load decline (vs. 0.29 in placebo) after 14 days when added to a failing regimen. At this point, treated patients switched to subcutaneous lenacapavir given every 6 months, along with an optimized background regimen. The study is ongoing (and includes a non-randomized arm), and 19/26 patients have viral suppression. Two experienced viral rebound with emergent resistance. Not much information about the background regimens used with this novel agent.

- The investigational NNRTI MK-8507 has a PK profile that supports once-weekly dosing. It will be paired with islatravir for treatment of HIV. The resistance profile is likely to be similar to doravirine.

- Further evaluation of daily versus on-demand PrEP with TDF/FTC shows a low incidence of HIV in both strategies. One wonders whether TAF/FTC would be this effective given on-demand — suspect it would be, but it has not been tested this way.

- Laboratory evaluation of cabotegravir PrEP failures in HPTN 083 was challenging. And that’s an understatement! The issue is that CAB delayed detection of infection using standard HIV testing algorithms (point-of-care antibody testing, standard 4th generation antigen/antibody tests). Also, a small number failed despite adequate adherence and measured CAB levels, with development of INSTI resistance. Should we be using viral load tests to monitor our patients on CAB-based PrEP? Likely yes.

- A cost-effectiveness analysis of long-acting CAB for PrEP suggested that it would not be cost-effective if priced similarly to cabotegravir-rilpivirine. Though CAB is more effective than generic TDF/FTC for HIV prevention, the estimated $17,000/year cost difference puts the cost-effectiveness ratio at more than $1 million per quality-adjusted life-year. A limitation of this analysis, of course, is that we don’t know yet what CAB for PrEP will cost!

- As both a pill and as a drug-eluting implant, islatravir moves forward as a long-acting PrEP option. The pill projects to be once-monthly; the implant could be yearly.

- In consecutive sampling of 1076 people with HIV (PWH) in Spain, 8.6% were seropositive for SARS-CoV-2. Those on TDF/FTC were less likely to test positive — even after controlling for underlying comorbidities (an adjustment not made in this group’s previously published paper).

- In a large national cohort with nearly 600,000 cases of COVID-19, PWH and solid organ transplant recipients were more likely to be hospitalized than controls. Both groups had a high burden of comorbidities — which increases the risk of adverse outcomes from COVID-19 for all groups, including those with HIV.

- A single infusion of bamlanivimab and etesevimab given to outpatients with COVID-19 at high risk for severe disease reduced the risk of clinical progression (hospitalization or death). There were no deaths in the treatment arm, 10 in placebo. Viral load decline and clinical recovery were also faster with treatment.

- Compared to placebo, the oral antiviral molnupiravir reduced the proportion of patients who had positive SARS-CoV-2 viral cultures by day 5. Unusual endpoint, but the results do demonstrate an antiviral effect. Several phase 3 clinical trials are ongoing, both in the inpatient and outpatient setting.

- Banlanivimab was effective in preventing COVID-19 in skilled nursing facilities. Those who did get COVID-19 despite treatment had lower viral loads and more rapid resolution of symptoms compared to the placebo group. While vaccination will undoubtedly be the mainstay of preventive strategies for COVID-19, in certain settings monoclonal antibodies may have a role.

- In another study of COVID-19 prevention, casirivimab plus imdevimab given subcutaneously to asymptomatic household contacts of active cases prevented 100% of symptomatic infections. Among those who did acquire COVID-19, viral loads were lower and PCR positivity was of shorter duration compared to placebo. Note the subcutaneous route of administration in this study, as it obviated the need for IV access — a big advance given the difficulty of arranging these treatments under the current Emergency Use Authorization.

- For 23 patients with refractory COVID-19 due to B-cell deficiency, convalescent plasma led to clinical recovery in 20. This population — receiving rituximab or similar anti-CD20 agents — has proven particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, often with prolonged symptoms and persistently high levels of virus.

- Treatment of hepatitis C with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir achieved cure in 95% of patients with minimal monitoring. And I mean minimal! (The study was called “MINMON”.) This single-arm study with 399 participants dispensed all tablets for a 12-week course at entry, had no on-treatment laboratory monitoring, and had just one week 22 visit to assess for cure (SVR). Aside from two phone contacts for adherence monitoring, that was it — amazing.

- Didn’t see all the plenaries or invited talks — attending a virtual conference can be strangely exhausting — but among those I did see, can highly recommend Dr. Shahin Lockman on HIV treatment in pregnancy, Dr. Jose Arribas on dual versus triple ART, and Linda-Gail Bekker on long-acting options for HIV prevention. Bravo!

You’ll note I started and finished this post mentioning hepatitis C studies — which due to our success in treatment now have a very small footprint at CROI. Let’s hope the same happens to COVID-19 in the not-so-distant future!

And since this CROI was supposed to be Chicago and bring in people from all over the country (and the world), here’s a wonderful tour around North American accents, with of course a stop in the land of da Bears — right around 3’40”.

March 7th, 2021

Exactly One Year Ago, a Memorable Dinner Before a Memorable Year

Feb 23, 2020.

On March 7, 2020, right before CROI here in Boston, a bunch of us ID types planned to get together for a pre-conference dinner. A mixture of Bostonians and out-of-towners who hadn’t seen each other for a while. A chance to catch up before our busiest (and most important) scientific meeting.

What happened?

One person landed in Boston, and promptly got the next flight back to Los Angeles.

Another canceled his flight and never left home. A shame, too, since he was bringing his new partner (whom I still haven’t met). I hear she’s really fun and interesting.

One had to stay home due to a no-travel ruling issued for all his faculty. (Those edicts had not yet come from Harvard, but would a week later.)

A fourth had arrived early for the conference, but was so busy setting up the now “virtual” CROI that dinner for her was out of the question.

And of course, attendees from Europe (especially) already had pulled out of the conference en masse.

You get the idea.

Our numbers for dinner were substantially down, but we still assembled with (mostly) locals. Indoors. Windows closed. It’s winter here in early March. Plenty of hand-washing and, befitting the fomite-centric perspective at the time about SARS-CoV-2 transmission, extra use of an alcohol-based hand sanitizer — something I’d never purchased before.

That evening was filled with lots of discussion about the Biogen conference. About China, Italy, Spain, and Iran, and what was undoubtedly coming our way soon. About our frustration with the lack of COVID-19 testing — we ID doctors spent all of February complaining about that, with no answers coming from anywhere. Just painful silence.

And, yes, lots of anxiety.

Now, as CROI starts up again — virtually, of course — I think back to that night. A dinner indoors with friends and colleagues, possible a year ago today but unimaginable since, could now again happen in our (fully vaccinated) future.

Not saying I know when it will happen — just that it could. Hope.

Wow, it’s been a memorable year.

February 28th, 2021

Another COVID-19 Vaccine — and Barney, Explained

Busy few days on the COVID-19 vaccine front, specifically related to the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine developed by Johnson & Johnson.

Busy few days on the COVID-19 vaccine front, specifically related to the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine developed by Johnson & Johnson.

February 26, the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee reviewed the data on the vaccine, voting unanimously that the benefits outweighed the risks.

February 27, the FDA granted the single-dose vaccine emergency use authorization.

And February 28-March 1, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) meets to discuss what recommendations to make about its use.

This means doses can reach us as early as this week.

What is this vaccine? Ad26.COV2.S is a recombinant replication-incompetent human adenovirus serotype 26 vector encoding a full-length, stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spike protein antigen.

In other words, quite different from the mRNA vaccines in current use, and hence requiring a whole new section to the NEJM Covid-19 Vaccine Frequently Asked Questions.

That’s a ton of work (for me), which is why this week’s post is so short.

But before I go, here’s the inspiration for citing an anthropomorphic dinosaur as my “animal spirit”, as requested by Dr. Gabriel Vilchez:

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 27, 2021

My friend Janet — a brilliant child psychiatrist — used to tell her pre-teen daughter why she couldn’t get a tattoo.

The reason?

Imagine if I had let you get a tattoo when you were 4 years old. You’d have Barney the Dinosaur on your body permanently. Who knows whether what you love now will be something you will love the rest of your life.

This was a highly effective message, one I’ll never forget.

February 21st, 2021

Why Are COVID-19 Case Numbers Dropping?

We don’t know. That part is easy.

Also easy is that case numbers really are falling — it’s not just reduced testing — and it’s happening pretty much everywhere.

Urban areas and rural. Red states and blue. Places with broad vaccine rollouts and those with hardly any. North and South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Even countries with the B.1.1.7 variant.

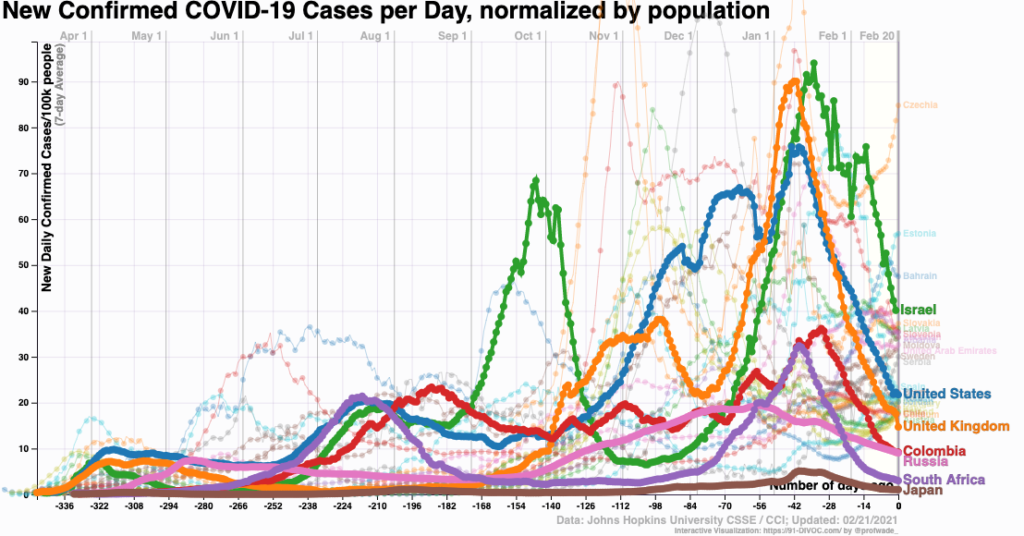

Look:

Let’s round up some theories:

1. Seasonality. An attractive hypothesis — coronavirus infections pre-SARS-CoV-2 definitely show a seasonal pattern.

And various viral diseases go through communities synchronized with the seasons, especially when school starts or the weather gets colder. Any pediatrician will tell you that.

Note that the term “seasonality” has always been a bit misleading — it refers to infections peaking within seasons, not throughout them. Think of influenza, how sometimes we have an early, sometimes a late seasonal peak in the winter.

The problem with this seasonality theory is that the seasons are flipped in the southern hemisphere. And didn’t cases surge over the summer in many southern U.S. states?

2. Herd immunity. Nearly 28 million Americans have had a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis reported to the CDC. This represents only a fraction of the true cases — especially the mild or asymptomatic ones — and the CDC estimates that only 1 in 4.6 infections are reported. That could bring us up to half the US population with some degree of natural immunity to infection.

Even as of mid-January, the CDC put the actual case numbers at over 80 million, and certainly it’s higher than that now. And note that in some regions, the actual case counts might be even higher — 5 to 20 times higher, according to one recent publication.

3. Behavior. We know much better now how this virus is transmitted. Avoiding crowds and indoor spaces with poor ventilation — and wearing masks — reduce the risk. But has our behavior actually followed suit?

The holidays are behind us. The Super Bowl was lousy. Not many parties for the Australian Open tennis finals. Spring Break hasn’t happened yet.

One compelling hypothesis, related to herd immunity, is that the people least likely to follow infection control advice — or unable to follow it based on work or living situation — already have had COVID-19 and hence are immune.

The others, not yet infected, watched cases surge in December and January and continue to hunker down and stay safe — or again, have the luxury of staying safe. They might be especially vigilant now that a vaccine is in their not-too-distant future — you know, the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, the light at the end of the tunnel, or the Holy Grail at the end of the Monty Python movie.

(Sorry about that.)

4. Vaccines. The world is vaccinating like crazy. Demand is off the charts. And in most places, we’re targeting the people most likely to have symptomatic or severe disease.

Plus, the data increasingly suggest that the vaccines reduce not just disease, but also the likelihood of transmission — they reduce infections overall (uninfected people can’t transmit), and those with infection have lower viral loads.

While the vaccine rollout is not yet broad enough to explain the case number drop on its own, it might be contributing. It certainly could be playing a role in Israel.

5. The virus. Maybe the virus is doing us a favor and becoming less virulent over time. Perhaps some of these variants — if not B.1.1.7 — in order to gain the ability to transmit, also cause less severe disease.

Take the virus’s perspective — yes, think like a virus — and how this would be evolutionarily beneficial. More mild cases, more chance to spread its genetic material to other susceptible hosts. That’s all viruses care about, right?

6. It’s a gemish. This brings us to the most likely explanation for the drop in cases, a gemish — Yiddish for a mixture of things. (It’s pronounced “ga-mish”, in case you want to try it out on your own.)

It could be all of the above explanations, in various proportions, and different in various regions — plus things no one has considered.

And the uncertainty about why cases are dropping again hearkens back to this great H.L Mencken quotation, which over time has morphed into this profound statement:

Every complex problem has a solution which is simple, direct, plausible — and wrong.

I stress the importance of being humble about not knowing why the cases are dropping simply because reliance on one of these factors over another could get us into trouble. For example, this week Dr. Marty Makary, writing in the Wall Street Journal, posited that we are already close to herd immunity, making this bold prediction:

There is reason to think the country is racing toward an extremely low level of infection. As more people have been infected, most of whom have mild or no symptoms, there are fewer Americans left to be infected. At the current trajectory, I expect Covid will be mostly gone by April, allowing Americans to resume normal life.

Warning — if anyone tells you with confidence that they know precisely why cases are dropping, and that they have an accurate crystal ball showing that by April we’ll be safely out of this pandemic — please view it with the appropriate scientific skepticism it deserves.

Look, we can hope this optimistic prediction is correct — we all want that. April isn’t far away, we’ll know soon.

But if there’s one thing a pandemic from a new human disease teaches us, it’s that there’s a lot we don’t know.

February 15th, 2021

Time to Fix the HIV Testing Algorithm — and Here’s How to Do It

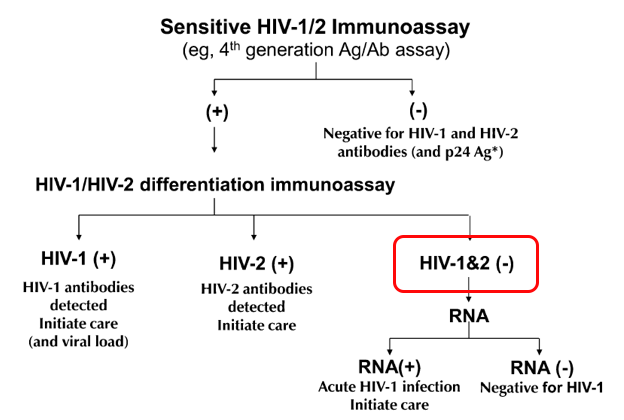

Remember the revised HIV testing algorithm that debuted in 2014? The one that was supposed to solve all our problems?

First, it included a “highly sensitive” screening test that started with a “4th Generation” combination antibody/antigen test. This decreased the window period between acquiring HIV and having a positive test, thanks to the antigen. Great!

(These “generation” analogies sure are common in medicine. Is there a line of inheritance? A royal family? Some black sheep?)

Second, it retired the HIV Western blot as the confirmation test, and substituted a “differentiation assay”, a test that distinguishes between HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies. This test is cheaper, faster, more sensitive, and automated, many advantages over the Western blot — may the latter R.I.P, it served us well for many years.

Hooray! All problems solved. A highly accurate diagnostic test in ID just got even better.

Well … not quite. The algorithm improved, but a major problem remained — what does it mean when a highly sensitive fourth-generation test comes back positive, but the differentiation antibody assay is negative?

In graphic form, this:

These indeterminate results are so frequent that it motivates by far the most common question we ID doctors receive about HIV testing — and was the subject of one of the most popular pre-pandemic posts ever on this site.

The problem is that these results represent two clinical states that are diametrically opposite:

- Acute HIV — a person who recently acquired HIV, and is still in the “window period” before antibody develops. Remember, the differentiation assay is an antibody test. It takes a while to turn positive, typically 2-4 weeks.

- False-positive HIV screen — a person who doesn’t have HIV at all.

In most clinical settings, the second of these (the false-positives) greatly outnumber the acute HIV cases. But we still have to bring back the patient to rule out acute HIV.

Which is a pain, and creates several more “worry days” before there is diagnostic certainty.

Ah, but what if you could just do an HIV RNA assay — a viral load — as the confirmatory test? And potentially not have to bring the patient back in at all?

Such a strategy is now feasible using one of the HIV viral load assays, the Aptima® HIV-1 Quant Dx. It’s the first quantitative viral load test that is also approved for diagnosis of HIV. Off a serum sample sent for HIV screening, the lab can run a qualitative HIV viral load with this assay, with results as follows:

- Non-reactive for HIV-1 RNA, or

- Reactive for HIV-1 RNA

The lab can detect whether the reactive test was < 30, between 30-10 million copies/mL, or >10 million — but the package insert says it won’t report those ranges, since the test isn’t approved this way.

(I should mention here that long-time HIV testing guru Bernie Branson says that says that the assay can report an actual number off of serum, albeit one that is likely lower than we get from plasma. Which makes us wonder whether a plasma sample can be collected for HIV screening, and reflexed to the accurate quantitative viral load — the subject of a collaborative modeling study led by my colleague Dr. Emily Hyle.)

With the HIV RNA as the confirmatory test, the vast majority of reactive HIV screens could quickly be resolved — a non-reactive result would be all but 100% reassurance that the screening test was a false-positive. And a reactive result would mean that person has HIV, and should start ART.

The differentiation assay will still be run if the HIV RNA is negative, as it will determine whether a person is either an HIV controller (has HIV with an undetectable viral load), or has HIV-2. But both are pretty darn rare.

So let’s go back to the confirmatory HIV RNA being reactive. Would this be sufficient information to start treatment, or would clinicians still want to collect a baseline quantitative result, then start ART?

I wondered about this, so here’s a little poll:

Hey #IDtwitter — if the HIV testing algorithm went like this:

1) HIV Ag/Ab screen – Reactive

2) HIV RNA confirmation – Reactive for HIV RNA (range 30-10 million)

Would you still send a quantitative VL before starting ART? Why or why not? @EmilyHyle @Hologic— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 13, 2021

A solid majority would still want this quantitative result, even while acknowledging it’s unlikely to change most initial treatment strategies. Here’s one of the best reasons why from Dr. Hana Akselrod:

Patients have mentioned the emotional impact of seeing the VL number come down by orders of magnitude, so that is now part of my motivational interview. Then we segue into U=U.

I agree!

Plus, HIV experts will note that two initial regimens — DTG/3TC and tenofovir/FTC/RPV — also have upper limit viral load thresholds that exclude them as options. (For these two, it’s 500,000 and 100,000, respectively.)

However, from a medical perspective, knowing the precise quantitative viral load usually would fall more into the “nice to know” than “need to know” category.

I’d bring the person back for a resistance genotype (another “nice to know” test) and a plasma quantitative viral load, and start ART (generally bictegravir/FTC/TAF or dolutegravir plus tenofovir/FTC) awaiting the results of these tests.

To summarize, it makes all kinds of sense to use an HIV RNA as the confirmatory test after a reactive HIV Ag/Ab screening test. It will reduce both “worry days” for those who test negative and speed up the time to starting HIV therapy for those who test positive.

Even better? Collect a plasma sample for the HIV screening test, and then use that for a precise quantitative viral load if the screen is reactive.

Now when can we make this change?

And since I haven’t featured a video in a while, how about this one, sent to me by a noted (but now retired) food journalist? How can you resist Weird Stuff in a Can?

We hope you enjoyed this week’s break from relentless 24/7 COVID-19 coverage. Have to mix things up a bit. Thank you for your understanding.

February 7th, 2021

Does Taking Vitamin D Prevent or Treat COVID-19?

Vitamin D supplementation — critical in prevention and treatment of COVID-19?

Or does it do nothing — except further enrich the vitamin and supplements industry, which is worth more than 100 billion dollars?

The challenge is figuring out which of these is the truth, and after several weeks of thinking about the issue, I find it’s far from straightforward — with many strong (and conflicting) opinions held by lots of smart people.

I waded into these choppy waters a couple of months ago with this post after seeing a pre-print of a negative vitamin D study:

Low vitamin D levels may correlate with worse outcomes in many diseases.

But supplementing does not necessarily improve outcomes. In fact, it almost never does.

(Still waiting for a truly convincing study in any infection.)

Lather, rince, repeat.https://t.co/RlqpSCPlRC

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) December 8, 2020

You can tell what my “priors” were on this research question. Most studies of vitamin supplementation in all diseases have ended with negative results — it’s really quite remarkable the sheer number — and in some medical problems the vitamin treatment arm actually does worse.

For vitamin D specifically, here’s a list of the negative randomized clinical trials done just in the past couple of years summarized by NEJM Journal Watch:

- Prenatal supplementation and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children

- Falls in older adults

- A range of physical and cognitive outcomes in adults older than 70

- Macular degeneration

- Bone density (this one surprised me)

- Childhood asthma

- Preventing depression in adults 50 and older

- Preventing TB in children

- Outcomes in critical illness

- Diabetes-related kidney function

- Bone density (again!)

For each of these disease areas, observational studies found an association between low vitamin D levels and poor outcomes, with a mechanistic explanation of why that might be, and how such adverse outcomes could be reversed with supplements.

But alas, all of the randomized trials were negative — no significant benefit. Not only that, the study on falls in older adults and one of the bone density studies actually showed worse outcomes with higher doses — never a good trend.

But I quickly learned that despite these negative studies, my skeptical view about vitamin D and COVID-19 is far from universal.

Indeed, the response to the post was surprisingly brisk, and quite polarized — some agreeing with the post that “association is not causation — basic principles.”

Others criticized the study design, in particular the eligibility criteria (too sick) and dosing strategy (daily dosing would be better). Someone sent me this hour-long video, a tour-de-force graphical explanation of how vitamin D is critical for prevention and treatment of COVID-19; another person sent this “Roll Call” of credible experts calling for vitamin D treatment.

Then a physician I know well from teaching together (a primary care doctor) sent me a 2017 meta-analysis of randomized trials on vitamin D supplementation to prevent viral respiratory tract infections. The studies included are mostly of good quality, and the aggregate results suggest a substantial benefit.

Perhaps this is why Tony Fauci says he takes a vitamin D supplement?

Now motivated to learn more, I reached out to Dr. David Meltzer from the University of Chicago. He’s the first-author on a nicely done study finding a strong association between low vitamin D levels and testing positive for COVID-19, and he kindly agreed to be interviewed in this OFID podcast about this paper and his ongoing studies. Highly recommended — he’s a smart, experienced clinical researcher, doing community-based randomized trials of various vitamin D interventions.

And there’s quite a bit of other research going on right now, as summarized nicely here in this review by Rita Rubin in JAMA. She also cites some inconsistencies in the research to date, along with a discussion of the funders of some of the trials — not surprisingly, companies from the supplements industry and labs that offer vitamin D tests.

So where do I stand on this vitamin D issue?

It seems highly likely that low vitamin D levels are associated with worse outcomes in COVID-19. Levels are a marker for various components of ill health — inactivity, poor nutrition, lack of fresh air and sunshine.

Conversely, taking vitamin supplements in observational studies often is associated with better outcomes. Whether this is because such people are more health-seeking, or whether the supplement is doing anything, isn’t possible to disentangle. For a perfect example, here’s a recent study showing that regular supplement takers of vitamin D were less likely to get diagnosed with COVID-19. But the benefit didn’t appear to be mediated by higher vitamin D levels.

As to whether taking a vitamin D supplement causally helps to prevent or treat COVID-19, many questions remain. Would it work in everyone? Or just those with low levels? (Essentially every citizen in Boston this time of year, I write, as the snow briskly continues to fall.) Or would it provide benefits only to those at high risk of severe disease? And if one recommends it for patients, friends, and family, what’s the right dose? And the best formulation?

Fortunately, my hospital colleague Dr. JoAnn Manson is leading one of the many studies evaluating vitamin D, both as COVID-19 prevention and treatment. She has extensive experience running large clinical trials, all done by mail/remotely, so if we’re going to get an answer, she’s the right person to do it.

My prediction? Odds are it won’t do anything. But I hope I’m wrong.

That’s why we do the studies!

And here’s the David Meltzer podcast stream, in case you want to stay on this page and look at our cute dog.

January 31st, 2021

Are We Expecting Too Much from Our COVID-19 Vaccines?

Photo by Wolfgang Hasselmann on Unsplash.

There are no absolutes in life. And nothing is perfect.

Tom Brady isn’t always in the Super Bowl (hard to believe). Serena Williams occasionally exits tennis tournaments in the early rounds. Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep sometimes appear in movies that are stinkers.

I’ve always thought that Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York fits horribly on Fifth Avenue, and looks like a toilet (not an original thought). Even the Beatles unfortunately released Revolution 9, an interminable abstract sound collage of musical “art” — my vote for their very worst “song”.

So why, then, are we expecting perfection from our COVID-19 vaccines? The vaccines developed in record time and our best chance at controlling the pandemic?

That’s what struck me late last week when we heard the results of two important COVID-19 vaccine studies, one from Novavax, the other from Johnson & Johnson.

Both vaccines worked, but there’s a distinct tone of disappointment in some of the news coverage.

In the Novavax trial, which used a two-shot protein-adjuvant strategy, the vaccine was 90% effective in the United Kingdom, but only 49% effective in South Africa, with most of the vaccine failures in South Africa the result of the B.1.351 variant.

Johnson & Johnson used an adenovirus 26 (Ad26) vector vaccine and one shot. It was only 72 percent effective in preventing COVID-19 in the United States and just 57 percent in South Africa.

(Italics mine, to make a point.)

With the 95% protection in the Pfizer and Moderna studies of mRNA vaccines, the headlines making unfavorable comparisons are understandable.

But there’s a lot to like about these results, even based on the limited information available in the press releases.

Both studies faced a more challenging COVID-19 transmission dynamic than Pfizer and Moderna — with a global surge in cases and emerging variants that are more contagious, potentially of greater disease-causing virulence, and harboring antigenic properties making them more evasive of vaccine protection. We simply don’t know how the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines would perform under similar pressures.

And both vaccines appear to prevent severe disease, a critically important endpoint. (Numbers are small in the Novavax press release, but still in the right direction.) Since it’s highly unlikely we’ll ever be able to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 from the planet, converting it from something that fills our hospitals into a nuisance respiratory virus — causing a mild cold or sore throat — is a welcome trade-off.

https://twitter.com/VirusesImmunity/status/1355149007220310019?s=20

Prevention of severe disease is something all of these vaccines appear good at, according to a summary by my Boston ID colleague Dr. Roby Bhattacharyya.

Or, as put quite succinctly by longtime vaccine expert Dr. Paul Offit:

You want to stay out of the hospital, and stay out of the morgue.

More good news — neither vaccine requires the kind of ultra-cold storage of the mRNA vaccines, a huge plus for distribution. And a one-dose strategy could greatly speed getting a larger number of people with at least some protection.

Meanwhile, in related news, reports of COVID-19 vaccine “failures” continue to make headlines, again making me wonder — why are our expectations so high? Did we really expect these vaccines to be perfect? We’re still in the middle of a pandemic, with only a small fraction of the population vaccinated.

Of course, cases of COVID-19 will continue to occur, even after vaccination. They are not 100% effective, even under the best-case scenario of a clinical trial. What we’re hoping for with vaccination is that there will be fewer cases, that they will be less severe, and hopefully less contagious.

I’m highlighting the distinction between “fewer/less” versus “zero” because there’s reason to expect that real-world effectiveness will not match clinical trial efficacy. We must guard against reports of vaccinated individuals who get COVID-19 as evidence that they don’t work at all.

We don’t know, for example, how they will perform in the frail elderly or the severely immunocompromised — people too infirm to participate in the clinical trials, yet appropriate targets for early immunization. Plus, the variants may make their effectiveness lower than in clinical trials, which is why sequencing of cases that occur after vaccination will be critical.

The true effect on disease incidence must await large, population-based studies — studies we’re likely to see relatively soon, such as these encouraging preliminary data from Israel, which so far has vaccinated a higher proportion of its population than any other country.

Meanwhile, let’s stop expecting perfection, carefully review the emerging research, and focus on getting as many people vaccinated as fast as possible.

And enjoy this amazing medley as a Revolution 9 palate cleanser.