An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 25th, 2022

Yes, Even ID Doctors Get COVID — Including Famous Ones

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, various public figures have contracted the disease.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, various public figures have contracted the disease.

Tom Hanks, way back in early March 2020, was arguably the first globally famous person in the world to test positive for the virus. The announcement came right as much of the world prepared to shut down. My friends and I were wrapping up what would be our last indoor poker game for over a year when the news broke.

“Tom Hanks and wife test positive for corona,” said my friend Scott, looking at his phone between hands. We all reflexively reached for the hand sanitizer I’d strategically placed beside each person’s chair. Hey, back then it was fomites — remember?

Hanks made the news public in a typically generous and optimistic way. He’s the nicest super-famous-rich person on the planet, isn’t he? And his COVID episode elicited sympathy, and hope for a quick recovery, for both him and his wife.

But he’s a beloved actor, and hardly the kind of person to bring out the meanies.

Because since then, in lockstep with a virus that has infected a massive proportion of the world’s population, we’ve had a veritable cavalcade of famous people come down with COVID.

Let’s see, off the top of my head — two presidents, one vice president, prime ministers, numerous other politicians, multiple actors, several radio and TV talk show hosts, athletes, rock stars. You name it.

Plus, Tony Fauci.

And now, my friend and former colleague, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky. The announcement came just as we were finishing our first in-person meeting, IDWeek — which, as I predicted, was filled with unmasked work-related and social gatherings in conference rooms, hotel lobbies, and restaurants.

“This Marriott must have some special anti-infective power,” said one of my colleagues. “Seems when you leave the convention center and enter the lobby, you no longer need a mask.”

So why bring up the CDC director’s case of COVID? Because it has elicited one of my least favorite aspects of the pandemic since it started — the tendency for some people to gloat about another person’s illness, criticize that person, and to use it as a way of endorsing their particular stance on the disease.

Look, I made no secret about my opinion on how our former president handled the pandemic in the spring of 2020. But when he came down with COVID in the fall of that year, in the pre-vaccine era, and got pretty darn sick, I never wrote, or even said Good — he deserves it. Same goes for the parade of COVID-denialist radio talk show hosts, whose deaths struck me as both pathetic and tragic.

Frankly, it pained me to hear some friends and colleagues take this stance, and I shared my views with them at the time. You’re reveling in the illness and misery of others? Doesn’t that make you feel yucky?

Same happened with Dr. Fauci, and now Dr. Walensky — the negative reactions come from all around. Anti-vaxxers and libertarians on one side, COVID-zero and public health zealots on the other. Implication? You’re responsible for the mess we’re in; now this is your just desserts.

It’s painful to see and makes me so uncomfortable. Because the reality is that we’re all struggling to do our best with this tricky virus, which was only discovered in early 2020 — and hence leaves us reading a very new, and sometimes non-existent, playbook. There is no person whose call on policies or predictions could be 100% right, 100% of the time. Doesn’t matter how smart or famous you are.

So here’s a bold idea — how about we treat every person’s illness with the kindness and compassion we’d want when our friends, our family members, and we ourselves get sick?

It’s really not so hard to do, is it? After all, we did it with Tom Hanks.

October 17th, 2022

Big In-Person Medical Meetings and Cognitive Dissonance for ID Docs

Dissonance: lack of agreement; inconsistency between the beliefs one holds or between one’s actions and one’s beliefs; a mingling of sounds that strike the ear harshly.

Dissonance: lack of agreement; inconsistency between the beliefs one holds or between one’s actions and one’s beliefs; a mingling of sounds that strike the ear harshly.

It started shortly after the chaotic, disruptive, and all together unpleasant Omicron wave of 2021–22.

It continued through the BA.2 and BA.5 surges, and now plays on through the swarm of Omicron variants that float all around us.

It’s the persistent background sound of an ominous minor chord signaling COVID cases to those of us who specialize in Infectious Diseases — never going away, waxing and waning in volume, all summer long and now into the fall.

That’s one of the two chords playing repeatedly and giving us information about test positivity rates, wastewater data, vaccine and treatment-evasive variants, and generating calls from patients, colleagues, friends, and family members about having COVID.

Undoubtedly this chord will be playing louder as winter arrives, along with variants BF.7, BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and who knows what else is in store. Respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, are seasonal, after all.

Playing at the same time is a different chord, in a happy major key — probably C major, no less. People hearing this chord can all but ignore that there’s plenty of COVID out there. Sniffles again are allergies, sore throats and coughs no more ominous than what they were before the pandemic. Meaning, not very.

COVID test for that mild sore throat? You’ve got to be kidding. Mask up for crowded indoor spaces? C’mon, that’s so last year.

Schools, restaurants, bars, concerts, big weddings, places of worship, gyms, travel — as noted here previously, all back to normal.

Most people don’t experience these two chords, playing simultaneously. But we do, we ID doctors — a scary chord in one ear, a happy one in the other.

Where does that leave us ID doctors? With a whole lot of dissonance — the sound of those two chords, major and minor, playing together. Minor if we’re caring for the immunocompromised and/or older and frail, or leading the infection control team at the hospital, or managing tight clinical schedules with people dropping out for 7–10 days for COVID, or responding to queries about COVID — the volume of which correlates perfectly with local wastewater concentrations of SARS-CoV-2.

But it’s a major chord if we’re trying to be like most “regular” people, just wanting to get back to a pre-pandemic life.

It’s an appropriate time to bring up this conflict, because we’re on the eve of our big professional meeting, IDWeek — first in-person IDWeek since 2019, which was, of course, the Before Times.

You won’t be surprised that this meeting of ID specialists has strict masking policies, and a vaccine requirement to attend.

You also won’t be surprised to hear that, like the rest of our species, ID docs can’t socialize if it involves eating and drinking without taking off our masks. Figure that half the motivation to attend these meetings (at least) is for this kind of networking. Or that many of us, in our non-ID time, have gone to weddings, parties, gyms, restaurants, concerts …

Some might call this hypocrisy. The very definition of two-faced — yes, literally! Masked while indoors at the meeting, unmasked while sharing lunches, drinks and dinners with colleagues we haven’t seen in ages. Hey, what’s it going to be, ID docs?

Others could argue it’s still rational to require masking at the meeting. As Dr. Priya Nori noted to me during a recent discussion on this topic, we’ll be reducing our risk of viral respiratory infections at least half the day — and some risk mitigation is better than none. This was my view when I shared being invited to a group work meeting that, to my chagrin, appeared to take place in a crowded basement closet. Couldn’t we do better on ventilation than that?

There’s validity to both of these views (hypocrisy vs. risk mitigation), though certainly Dr Nori’s is the kinder and more generous one.

But I have another interpretation. I think we’re just confused. And nervous. And tired. And humbled. And, speaking for myself, we’re collectively suffering through a bit of PTSD, recalling the last two really awful winters, and for those of us from certain urban centers, the nightmarish March–April of 2020.

We can certainly hope those days are behind us, that our vaccine and infection-induced immunity continues to attenuate the severity of disease, that our ICUs and ECMO machines will remain unstressed, our elective surgeries not postponed.

But we don’t know that. Hence the dissonance.

And I hear it, and suspect everyone attending IDWeek in Washington DC this week will hear it too.

October 10th, 2022

Molnupiravir Results in PANORAMIC Study — It’s Not All Bad News

Last week, the large PANORAMIC trial of COVID-19 treatment in outpatients with mild-moderate disease appeared in a pre-print. This large (25,783 participants!) randomized, open-label study compared molnupiravir vs. usual care in adults 50 or older, or having comorbidities known to make severe disease more likely.

The results?

Molnupiravir vs standard of care for outpts with Covid19. No difference in the already low rate of hosp/death, but take a look at this Time to Recovery 2ndary endpoint, a 4-day benefit! Robust across subgroups. Caveat: Open label design. https://t.co/t07aqg68s9 h/t @ASPphysician pic.twitter.com/MExXZLOTp2

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 6, 2022

Four days faster recovery with treatment! You might think this would be welcome news.

Ah, but think again. Because the response from the ID cognoscenti was lukewarm, and that’s putting it kindly.

Many cited the study’s open-label design as a major limitation, negating the favorable time-to-recovery result. The placebo effect is certainly in play when a person knows they are receiving active treatment.

Some noted the ongoing concerns with molnupiravir and mutagenicity — and the theoretical worries about generating variants.

Others criticized the cost of the drug.

But the major theme of the naysayers emphasized the inability of the treatment to demonstrate a benefit in the primary endpoint of interest — hospitalization or death. Here the result was quite low for both arms, and equal, at 0.8%. Not a bit of difference, and this lack of efficacy is also what the headlines typically featured.

As a result, when I polled people on whether they would prescribe molnupiravir now that they know the results, it didn’t surprise me that a majority said no.

Molnupiravir vs usual care in large open-label randomized trial. Pts mostly vaccinated; omicron era:

– Primary endpoint: no difference in hosp/death (0.8% for both)

– 4.2 days faster reported recovery

– faster viral clearance

– serious AEs 0.4% for both

Would you prescribe it?— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 8, 2022

With the caveats that this sort of poll is only representative of the people who saw and answered it, and that Twitter can be a really negative place — like “staying too late at a bad party full of people who hate you” — I do think it’s worth acknowledging these important concerns about both the study and the drug.

But it’s also worth highlighting the good news coming out of this trial — and it’s very good news indeed.

First and foremost, the amazingly low incidence of hospitalization or death underscores how much less severe COVID is now compared to when it first hit the human race. It’s especially notable since the study population included only those at risk for bad outcomes. When it comes to most infections, it’s a wonderful thing not to be immunologically naive, and the participants had very  high rates of vaccination and/or prior infection.

high rates of vaccination and/or prior infection.

(Parenthetically, the lower disease severity presents a virtually insurmountable challenge to conducting a clinical trial with this “hospitalization or death” endpoint — as noted by Dr. David Boulware, the sample size would need to be extraordinarily large.)

Second, let’s go back to the observed faster time to recovery for a moment. A 4.2-day improvement in time to recovery with no major short-term side effects — or drug interactions — is nothing to sneeze at, if you’ll forgive the very apt cliche. As a point of reference, this is quite a bit more than the observed clinical benefit seen with oseltamivir and baloxavir for influenza, which is typically 1-2 days. Note also that there is no mention of clinical or virologic rebounds, though perhaps the researchers did not assess for these endpoints.

So let’s imagine you are a person with COVID. You’re miserable — feverish, sneezing, coughing, out of work. Not hospitalization-level sick, but feeling pretty lousy.

Your doctor tells you they have a 5-day treatment that, in a large study, shortened the time to recovery by 4-5 days compared to people who didn’t get the treatment.

Plus, there were no major side effects, and the amount of virus dropped faster, too.

Wouldn’t you at least consider it?

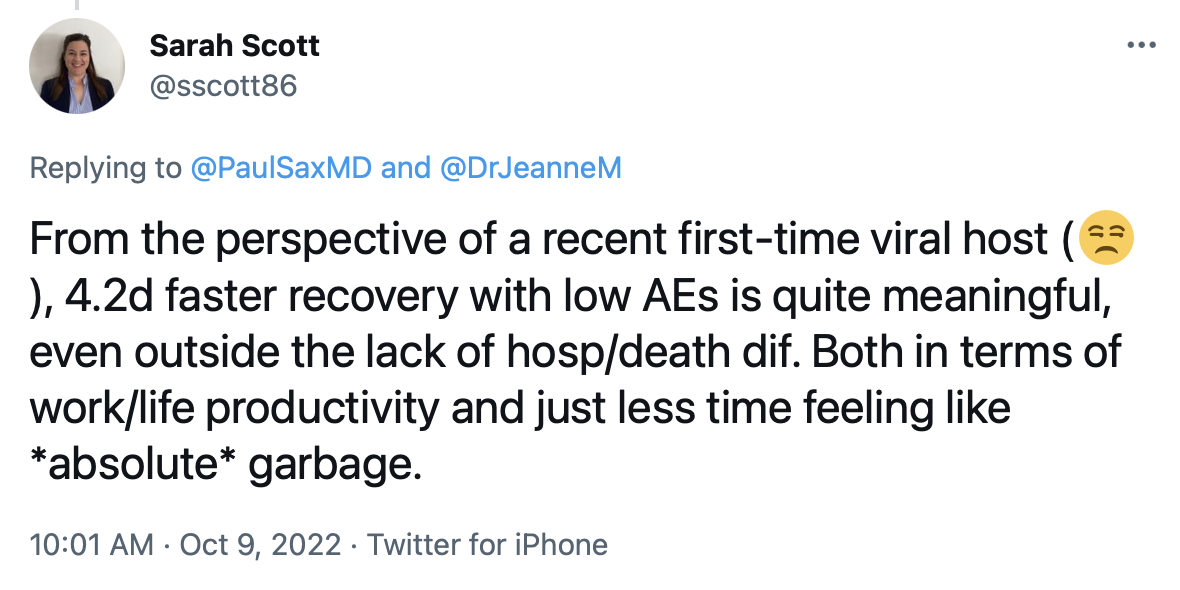

Or, as Dr. Sarah Scott writes:

Well said. While acknowledging that the open-label design makes ascribing this benefit solely to the drug is impossible — people really want to believe that their treatment is making them better — we can also note that this difference in time to recovery is substantial, even by the standards of other non-placebo controlled trials.

Finally, the PANORAMIC investigators deserve a ton of credit carrying off this very large, pragmatic clinical trial. We all look forward to seeing it go through peer review and revision, information about rebounds (if they happened), as well as the promised follow-up data regarding long COVID. Also, the results of the nirmatrelvir/r (Paxlovid) arm of the study promise to be particularly interesting, as this is way more widely used than molnupiravir for COVID treatment, at least here in the United States.

Meanwhile, enjoy this video, because I certainly did.

September 28th, 2022

Even if You Think “The Pandemic Is Over” — Let’s Make In-Person Meetings Safer

“The pandemic is over.”

“The pandemic is over.”

Someone very famous used these words recently, triggering all kinds of controversy.

While most ID clinicians groaned at the comment, knowing that it would be taken out of context, repeated in headlines without any of the President’s cautionary statements, and fuel COVID denialists, it’s also worth acknowledging that most of the country really does feel this way.

Look, if at least 90% (rough estimate) of travelers at Boston’s Logan Airport no longer wear masks, either while waiting for their flight or on the plane, it must be 99% in most other U.S. airports.

(I checked with my colleagues in other cities. It is.)

Plus, schools are open, restaurants busy, concerts and sporting events full. Postponed weddings are happening. People again travel for business and academic meetings.

If we haven’t returned to prepandemic “normal,” whatever that is, we’re certainly heading that way. Why? Because you’d have to be a hermit if you either haven’t had COVID yourself, or don’t have several close family members or friends who’ve had it — sometimes multiple times — and recovered uneventfully.

“The flu I had a few years ago was much worse,” said one of my own friends this week, walking his dog in our neighborhood, and looking just fine.

In short, the infection remains incredibly common, likely will get most if not all of us eventually, and — here’s the fact — just isn’t as severe as it once was, mostly because of vaccines and prior infection-induced immunity. All these things are true.

This is the part of the post where I need to insert these critical and essential caveats. Some people still get quite sick from COVID — I worry in particular about those with weakened immune systems. Some people will get long COVID. And testing positive is still enormously disruptive, forcing people into isolation and wreaking havoc on schools, workplaces, daycare centers, and many carefully planned events. In short, COVID still s–ks.

You can quote me on that. Colds, flu, RSV, and company are pretty lousy too.

But as part of the improvement in the prognosis for COVID, and the opening of our society (even for ID docs) to multiple activities that previously had been cancelled, I want to address one in particular — and that’s in-person meetings.

We can’t make them 100% safe. Can we at least make them safer?

So far I’ve traveled to three, and of course my colleagues have started doing the same. IDWeek is coming up in October, CROI in February, and these meetings will undoubtedly include many meetings and unmasked social interactions that could spread both COVID and other respiratory viruses. I get that.

But mitigating strategies are still welcome. One such meeting at IDWeek specifically cited that it would take place in a room “that has accordion doors so it can be opened up for airflow, as well as a wrap-around balcony.” Terrific. Ventilation is good — it’s one of the major lessons learned during the pandemic.

Another meeting asked us to do rapid antigen tests on arrival. No, these tests aren’t perfect, and they don’t screen for other respiratory viruses, but the positive predictive value of them is high. I’d welcome a cluster randomized trial of testing vs. no testing prior to in-person meetings.

So let me share an example of what not to do, “pandemic is over” notwithstanding.

I recently went to a meeting of other ID specialists, and planned ahead of time to be unmasked during both the meeting and the lunch. I figured we ID docs would not attend if we had a respiratory illness. We’ve gotten good at that, avoiding illness “presenteeism,” and most people with contagious respiratory viruses have symptoms. So that was some reassurance.

But here’s the not-OK part: The meeting took place in a tiny, crowded, low-ceilinged room, with barely a few inches between seated participants — the very converse of “social distancing.” If someone had one of those CO2 meters placed strategically in the center, I suspect it would have been sounding its alarm from the first 30 minutes.

The room was small enough that multiple people commented about the forced intimacy, making jokes about how ironic it was that we ID doctors would be sharing so much mutual air over the next several hours — especially because it was a beautiful fall day. “We should have the meeting outside,” said one of the organizers. Ha ha.

Yep, it was packed in there — if not quite phone booth stuffing or Marx Brothers-stateroom tight, certainly much more crowded than any meeting room I’d been in for years. Let’s just say it’s a good thing we all showered after our morning run or time on the elliptical, because any hygiene infractions would have been immediately evident. Lunch, fortunately, was in a much larger, well-ventilated room.

So I wore an N95 mask during the meeting. I was the only one.

Because COVID still s–ks.

https://youtu.be/NWFl2S5-Ua0

September 8th, 2022

A Back To Work ID Link-o-Rama

Zelda, Zoe, and Louie on the cover of their latest album, Parallel Paws. With apologies to Debbie Harry and Chris Stein.

A few nuggets are rattling around in the inbox post Labor Day, including this extraordinary photo of our family dogs Zelda, Zoe, and Louie, posing for their latest album cover.

Woof!

Besides, I haven’t done one of these Link-o-Ramas since January 11, 2021! That was either 20 months ago or 20 years, hard to keep track of time these days.

Enough with the introduction. On with the links — starting with some highlights from this year’s 2022 AIDS Conference in Montreal:

- Should people on PrEP or with HIV with a recent history of bacterial STIs take doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis after sex? The cleverly named doxyPEP study showed a marked reduction in all bacterial STIs, including gonorrhea — a benefit not observed in a similar study conducted in France. And living in New England, I am, of course, reminded of post-tick bite doxycycline every time I hear about this strategy!

- Treatment of people with HIV/hepatitis B co-infection with BIC/FTC/TAF led to more favorable hepatitis B outcomes at 48 weeks than TDF/FTC plus DTG. These results suggest that TAF should be preferred over TDF for coinfection treatment. FYI, these were two of the three potentially practice-changing studies presented at this year’s 2022 AIDS Conference. (The third study, using injectable cabotegravir-rilpivirine in PWH with viremia, I’ve covered in more detail previously.)

- Another person with HIV has been cured with a stem cell transplant from a CCR5-negative donor. While this “City of Hope” patient with AML is just the fourth (or fifth, if you count the mystery Dusseldorf patient) to be cured, each cure case adds to our understanding of how we might accomplish this one day with more practical methods.

- This example of “exceptional” HIV control may give us an alternative to a sterilizing cure of HIV. Diagnosed with acute HIV in the 2000s, with a baseline HIV RNA of 70,000 and CD4 of 800, she was treated with ART and a grab-bag of immune based therapies (cyclosporine, IL-2, interferon, GM-CSF). Now off ART for more than 15 years with stable CD4s and an undetectable HIV RNA, she has a steady decline in the HIV reservoir with “enrichment of memory-like NK cells and CD8+ gamma delta T cells with NKG2C.” Sure. As always with such isolated cases, how much can we attribute to our interventions, and how much to a one-off very fortunate immune response?

- Targeted versus “shotgun” metagenomic sequencing on sonicate fluids derived from patients with suspected prosthetic joint infection had comparable yields, with the former being less expensive and having a faster turnaround time. Note that it detected potential pathogens in 48% of culture-negative PJIs. How long before such molecular testing becomes standard of care?

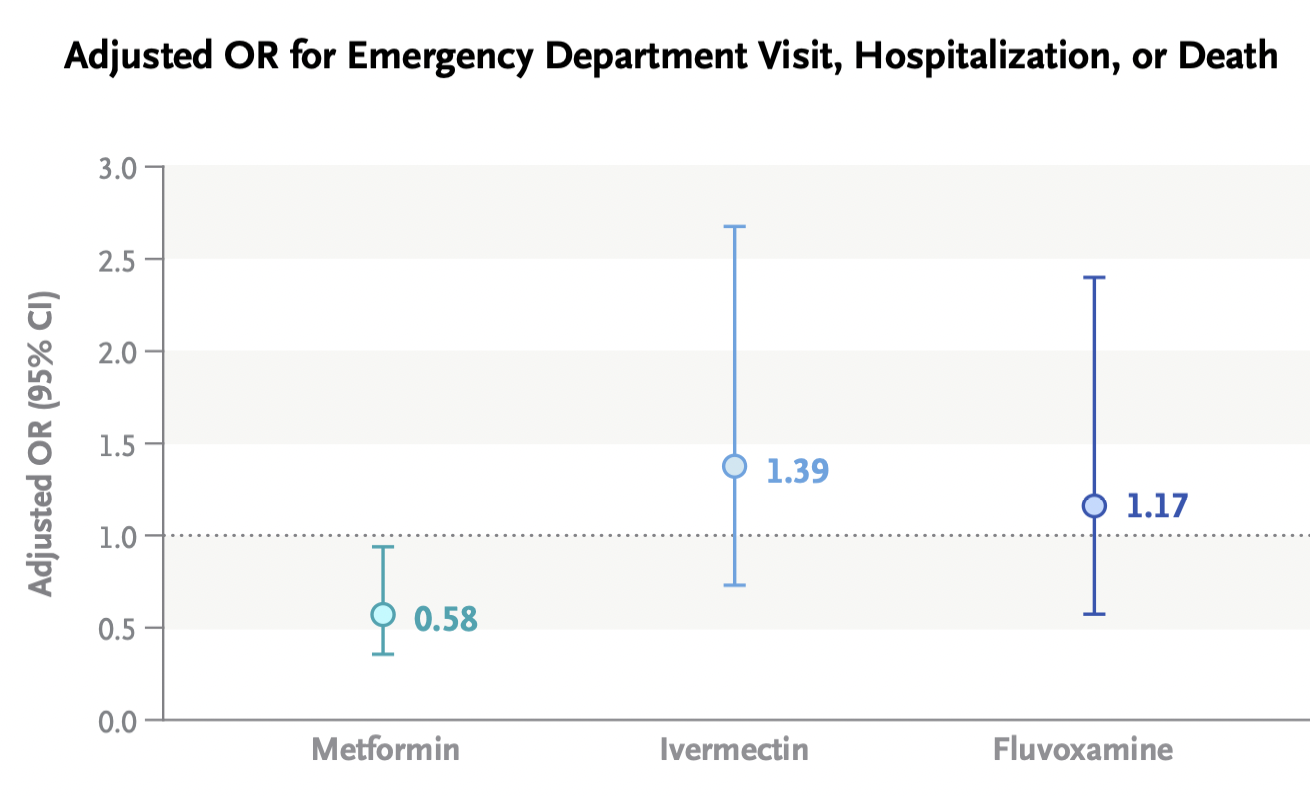

- A randomized clinical trial comparing ivermectin, fluvoxamine, and metformin to placebo for outpatients with COVID-19 found no significant difference in the primary outcome compared to placebo. One can be encouraged, however, by this signal from the metformin arm by looking at the secondary outcome of emergency department visit, hospitalization, or death. For a detailed further discussion of this interesting study by Dr. David Boulware, a co-investigator, read here. Note that a higher dose fluvoxamine strategy (which worked in the TOGETHER trial) is part of the ongoing ACTIV-6 clinical trial.

- Metformin shows up in numerous ID-related studies. In addition to its pleiotropic endocrine and anti-inflammatory effects, we can add antiviral activity against KSHV, SARS-CoV-2, Zika, and dengue, and a potential adjunctive role in tuberculosis, among others. And if you want to go further down this metformin rabbit hole, it’s not just being looked at for infection!

- A systematic review suggests that doxycycline for community-acquired pneumonia could make its way into the next guidelines. Resistance to azithromycin and the toxicity of fluoroquinolones make this a highly desirable option. Great accompanying editorial by the legendary Dr. Daniel Musher.

- Do either vaccination or prior infection reduce a person’s infectiousness when they contract COVID-19? Once we get past the fact that neither eliminates the risk of transmission — nothing is 100%! — we can at least cite several studies that prior immunity to SARS-CoV-2 reduces transmission risk, including this recent one done in a prison setting. Such data may point to a more stable time without marked surges, as community-wide immunity from either vaccine or infection or both could flatten rapid spikes in transmission.

- China has approved an inhaled vaccine for COVID-19. Used as a booster strategy after prior vaccination, the adenovirus-based vaccine induced humoral, cellular, and mucosal immunity. It’s the mucosal immunity that we hope will be more effective in blocking infection than our current vaccines. This is a big challenge, so it’s fortunate that many — around 100! — inhaled vaccines are under investigation.

- Are we treating peripartum infections appropriately? This review appropriately challenges the 2017 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines, which remarkably (and weirdly) still recommend ampicillin (or clindamycin) plus gentamicin — despite the fact that resistance to ampicillin is common, the dosing of these two drugs is complex, aminoglycosides penetrate poorly into abscesses, and the longtime availability of several safer and likely more effective options — such as piperacillin-tazobactam. “Get with the times” indeed!

- Treatment of cerebral toxoplasmosis with TMP/SMX appears to be as effective and less toxic than pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine. It’s also way less expensive, and much easier to take. This excellent systematic review could (some would say “should”) be guidelines-changing, as there is unlikely to be another prospective clinical trial conducted anytime soon, and most of the world already has made the switch.

- People who inject drugs admitted with complicated S. aureus bloodstream infections (including endocarditis) should be offered oral antibiotics at the time of discharge if they can’t safely continue intravenous therapy. Outcomes are significantly better than no antibiotics and comparable to IV after 10 days of IV treatment. Some would say switching to oral therapy should be the default option already — for everyone, if possible.

- In pregnant women, dolutegravir-based ART was superior to atazanavir–ritonavir, raltegravir, or elvitegravir–cobicistat in achieving viral suppression at delivery. It was similar to darunavir- and rilpivirine-based regimens, but the former is suboptimal due to twice-daily dosing, the latter because of food requirements and contraindicated acid-reducing therapies. With dolutegravir as the preferred option right now, we urgently need similar observational data on bictegravir/FTC/TAF, which is extensively used in clinical practice.

- Should linezolid replace clindamycin as adjunctive therapy for severe group A strep necrotizing fasciitis and toxic strep syndrome? Rates of resistance to clindamycin among beta strep species are high, and linezolid has similar in vitro suppression of toxin production. Makes sense. But file this one under the long list of questions for which there will never be a randomized clinical trial.

- SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen was detected in a majority of patients with long-COVID, or PASC. In 12 who had longitudinal samples, detection lasted 2-12 months. These results, if confirmed, imply a persistent reservoir of active viral replication, viral antigens, or both — and could lead to diagnostic tests and treatments, both of which are now sorely lacking.

- A clinical trial in the United Kingdom is testing tecovirimat treatment for monkeypox infection. Conducted remotely, with any clinician eligible to refer participants, the PLATINUM study tests tecovirimat 600mg twice daily for 14 days versus placebo on the rate of recovery and time to viral clearance assessed by weekly self-taken swabs. A similar study in the USA, run by the ACTG and called STOP, is expected to start soon.

Non-ID section:

- Even non-tennis fans might like this 2012 story about Frances Tiafoe. Written when he was just 14, the piece describes the childhood of the now 24-year-old Tiafoe, the first American man to make US Open semifinals since 2006. Stories like this definitely make me feel more patriotic than any shallow flag-waving! Tiafoe will certainly have his hands full tomorrow when he faces tennis wunderkind Carlos Alcaraz!

- A cardiac surgeon continued to operate despite a record number of malpractice suits, bad patient outcomes, and concerns raised by colleagues. At the very core of this terrifying story — as with many similar examples — is the strong financial incentive for hospitals to hold on to their “superstar” surgeons given the high revenues they bring in. Awful awful awful.

- Here’s a great depiction of participant behavior at scientific meetings. Well done, Dr. Ilan Schwartz!

Extroverts and introverts at conferences https://t.co/c6lm45DjKv

— Ilan Schwartz MD PhD (@GermHunterMD) September 7, 2022

Seems particularly appropriate for us ID doctors, as we gradually return to in-person big public meetings.

- The rock group Blondie released a deluxe box set celebrating the years 1974-1982. In case you’re wondering about the inspiration for the photo at the top of this post, this classic album was released 44 years ago this month, became a prominent part of the soundtrack of my college years … and it wasn’t called Parallel Paws!

Anyway… the earworms all day have been Blondie so I'm going to listen to the first three albums back to back. Pure pop. They were the best singles band in the world for a couple of years there. Parallel lines is pretty much perfect. #FridayNightIsMusicNight pic.twitter.com/tg6eMvPK70

— anthony vickers (@untypicalboro) September 2, 2022

(Dog photo by Hollis Rafkin-Sax, edited by Anne Sax, based on a design idea by … me.)

August 16th, 2022

Story as Evidence — Our Story

Edvard Munch, Towards the Forest II, 1915.

JAMA has a long-running and quite wonderful weekly feature called A Piece of My Mind, in which clinicians (mostly physicians) write about the human side of medicine. Not the place for dry descriptions of study designs or laboratory methods, A Piece of My Mind instead welcomes anecdotes, opinions, and emotions.

After all, as Drs. Preeti Malani and Jody Zylke wrote in a 2020 piece celebrating 40 years of the column, “physicians treat patients, not just their diseases, and confront complicated issues and circumstances daily.” In many of the columns, the table is turned, and the physician-writer shares what it’s like to be the patient — the person on the other side of the stethoscope, the scalpel, the chemotherapy infusion, or the psychotherapist’s office.

There’s a real strength to this form of communication, which at times can exceed the influence of even the best-designed clinical trial. While a single case might not stand up to a rigorous statistical analysis, a compelling story about a single patient — either as the caregiver or the person receiving the care — can have remarkable power.

Dr. Louise Aronson brilliantly described this phenomenon in a 2015 submission entitled “Story as Evidence, Evidence as Story.” She wrote:

In the public arena, the N-of-1 personal experience is considered not only data worthy of consideration but also sufficient to establish expertise. With a frequency and consistency that should make those who question the role of anecdotes in discussions of medicine and science rethink their position, a single, well-told story of human suffering trumps the most eloquent explanation of a large-scale trial.

I thought of this “Story as Evidence” phenomenon when hearing that the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, which eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion after nearly 50 years. Naively, I thought growing up that this right to choose would never be taken away.

Why is this relevant to A Piece of My Mind?

Because my wife and I have our own story to tell, now more than 2 decades old, and JAMA was kind enough to publish it this week.

August 8th, 2022

Long-Acting Injectable HIV Therapy for People Who Won’t Take ART?

Atlas. Lee Lawrie and Rene Paul Chambellan, 1937.

HIV treatment is so spectacularly effective that you might be surprised to hear that some people with HIV still have uncontrolled viral replication. We HIV clinicians watch with frustration and sadness as they experience progressive immunodeficiency, complications from advanced HIV disease, hospitalizations, and HIV-related deaths. Plus, while viremic, they continue to risk transmitting the virus to others.

What’s the barrier to successful treatment? In 2022, it’s almost never drug resistance. It’s that they can’t, or won’t, take oral antiretroviral therapy. Excluding those completely out of care (that’s a different problem), I’d estimate from various studies that they typically represent around 5% of a clinic’s population.

The percentage with uncontrolled HIV is higher in places like Ward 86, the safety net HIV clinic at UCSF — around 15% by their estimates. True to its mission, the clinic serves many people struggling with poverty, substance use disorder (especially cocaine and crystal methamphetamine), unstable housing, psychiatric illness, and low medical literacy. That’s why the case series they just published using long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine (CAB-RPV) is so remarkable.

That’s right — cabotegravir and rilpivirine for this highly challenging patient population, a group most certainly underrepresented in the pivotal clinical trials ATLAS and FLAIR.

Out of 132 people in Ward 86 referred for CAB-RPV treatment, 51 started injections. Of these, 39 patients had at least two treatments and were included in this report. The good news: All those with virologic suppression at baseline maintained HIV control during the follow-up, a tribute to the enhanced care provided by the team of clinicians involved in the program.

But by far, the most notable aspect of this report is what happened to the 15 people who were not on suppressive ART — in other words, the group highlighted in the first paragraph of this post, those not taking their meds.

This viremic group had a median CD4 cell count of 99 and a viral load of around 50,000 (with one over a million); a patient with resistance to raltegravir and elvitegravir (harboring the N155H mutation) was also treated. Despite these unfavorable baseline characteristics, 12 of 15 achieved virologic suppression (including the person with N155H), and the other 3 have HIV RNA that has declined by more than 2 log.

Although long-acting CAB/RPV is FDA-approved only for PWH w/ viral suppression, this remarkable case series (new in @CIDJournal) shows it can work also in those with viremia — where it could be a life-saving intervention. Clinical trials urgently needed. https://t.co/GvBQ0AtEvC pic.twitter.com/Z38ybgyLoe

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) August 4, 2022

Wow.

These exciting results notwithstanding, it deserves emphasis that using CAB-RPV for viremic patients takes us way outside the indications outlined in the FDA approval. This specifically stated that the treatment is for those “who are virologically suppressed (HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL) on a stable antiretroviral regimen with no history of treatment failure and with no known or suspected resistance to either cabotegravir or rilpivirine.”

There are plenty of additional caveats about using CAB-RPV in people not taking oral ART. The study includes just a small number of viremic patients, and the follow-up is relatively short (less than a year). We can’t say whether virologic suppression will be maintained, or what proportion will drop out of care and miss their injections, or how many will develop the much-dreaded two-class drug resistance to both integrase inhibitors and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors — resistance that will make subsequent treatments much more challenging. Plus, payers in some regions may not be as generous in covering treatment for a non-FDA approved indication.

It’s also worth remembering that Ward 86 is a special place, hardly representative of most HIV, ID, or primary care clinics. They have tons of dedicated on-site resources to enhance the care of their difficult-to-reach patient population. This includes doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers — a veritable army of people available to support and chase down people who might go astray while on HIV therapy.

Example: Two of the patients in this report with unstable housing received injections in the community with “street-based nursing services.” (When I wrote “chase down,” this is what I meant.) How many of us HIV providers have access to this kind of wraparound care? In other words, if you’re in a standard ID or HIV clinical practice, don’t try this at home quite yet.

These caveats notwithstanding, I maintain that this novel use of CAB-RPV is highly important, and that it’s critical it be explored further. Up to this point, our options for people who won’t take oral ART have been highly limited. In desperate cases, we’ve even resorted to feeding tubes to administer ART, these placed during prolonged hospitalizations for AIDS-related complications. If CAB-RPV can provide even half the people who won’t take oral ART an effective option, use in this population will be save more lives than CAB-RPV will through its FDA approved indication. After all, those people are by definition doing well on ART!

The alternative to trying this might be an HIV-related death. And no one in 2022 should die of AIDS without our doing everything we possibly can to get them on antiretroviral therapy.

Even if that includes an unapproved use of cabotegravir and rilpivirine.

July 22nd, 2022

The Paperwork Demands for Academic Medical Teaching Are OUT OF CONTROL

Playing at Bubbles, Piercy Roberts, 1803.

Why all caps in the above title? It’s to call attention to a problem that’s getting worse each year in academic medicine, especially when it involves teaching or talks.

The requirement to submit a veritable truckload of forms, documents, attestations, and summaries, all due months before the actual event.

Let’s explore in more detail what this might involve — and I assure you, what is outlined below is no exaggeration.

After accepting an invitation to teach, give medical grand rounds, or visit an academic medical center, you might receive an email from a “person” with an anonymized email such as “Internal Medicine Administrative Services” or “Medical School Education Coordinator.”

You know those emails that you dread to open because they have so many attachments that you barely know where to start?

Some of these emails have four or more attachments, plus additional secure links (which may ask you to create usernames and passwords), and numerous deadlines for all the required documents. Can an email weigh a lot? If so, these email behemoths are comparable to the Wile E. Coyote’s anvil on the Road Runner cartoons, the 16-ton weight from Monty Python, or Laurel and Hardy’s pianos.

If such emails fill you with dread, it’s because of the Fifth Law of Thermodynamics — otherwise known as Sax’s Law of Email Avoidance: A person’s reluctance to open an email and deal with it promptly is proportional to the square of the number of attachments. Example: An email with four attachments is 16-times more likely either to sit unopened and/or not get completed efficiently than one with only a single attachment.

Now let’s review the required items:

- Last name, first name, degree(s).

- Hospital and academic titles.

- Head shot. When submitting this photograph, those of us of a certain age might be tempted to choose something from a couple of decades ago. Fountain of Youth.

- Presentation title and date. It’s slightly annoying that all of this information from these first four items is either already known to the inviters (certainly the date) or available via a simple web search, but I’ll grant them these requests as we’re just getting started.

- Updated Curriculum vitae. Got to check those qualifications!

- Abbreviated biography. These are those braggy paragraphs that a person writes to help with introductions. Maybe I’ll include the fact that I won an essay writing contest about yogurt several decades ago for Boston’s Real Paper — or was it the Boston Phoenix? — allowing me to be on a panel of taste testers to identify Boston’s best brand. Or that I listed in my college yearbook that I was a member of a club called the “Leverett Luggage Society,” a club that did not exist.

- PHI query and permission form. PHI stands for “Protected Health Information,” meaning identifying information about patients. If any of this information is in your talk, it will require an additional signed form from the patient. Note to teachers everywhere — unless absolutely necessary, try not to include PHI in your talks. Seriously. Just not worth it. You can use a case-based approach to teaching, but modify the case sufficiently so that it does not include identifying information.

- Three (sometimes four) learning objectives. Before submitting these, you could be referred to “OCME requirements” for guidelines on how to write good Learning Objectives — these might come on a separate attachment — or you could be referred to the OCME web site. “OCME,” in case you’re wondering, stands for Office of Continuing Medical Education, not Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, or Orange County Model Engineers. The last of these, I’ve learned, was founded in 1977 and offers free rides on trains that operate like real locomotives, but are 1/8 the size of the real thing. See what can be learned from a quick web search? And before going on, I could write an entire post on these “learning objective” requirements which, as I’ve noted before, rarely lead to more learning, but sure are annoying to write.

- OCME disclosure of relevant financial relationships. Every talk requires this information — it’s a list of potential conflicts of interest — but despite the universality of this requirement, there are as many different forms for this information as there are stars in the sky — like snowflakes (to shift metaphors), no two are alike. How about all these Orange County Model Engineers hop off their mini-trains and come up with a standardized form? For a while I just submitted a Word document that listed potential conflicts of interest, and wrote in caps on all the proprietary forms — “SEE ATTACHED DOCUMENT.” That worked for a while, but nobody accepts that one anymore.

- OCME mitigation of relevant financial relationships. And if you do have some relationships, you will need to fill out an additional form, one which includes multiple questions (often as many as a dozen) to satisfy the organizers that these potential conflicts can be resolved. Here’s an example, taken from a recent form: “If I am discussing specific healthcare products or services, I will use generic names to the extent possible. If I need to use trade names, I will use trade names from several companies when available, and not just trade names from any single company. My learning objectives may not include trade names. (Check Agree or Disagree.)” Easy for me — I’m one of those nutty ID docs who says “trim-sulfa” rather than Bactrim, “cephalexin” rather than Keflex, and “pip-tazo” instead of “Zosyn,” both because I hate using trade names (especially when the drug is long off-patent), and because the last one always reminds me of Led Zeppelin’s 4th album, which is distracting.

- A list of references, and a PDF of a relevant published paper. If you’re really unlucky, there will be a requirement for an annotated bibliography, explaining why this paper was selected for this talk — oh the pain. For medical schools out there reading this post, please don’t get any ideas. “PDF,” by the way, stands for Portable Document Format, not Probability Density Function, or Pigs Do Fly. Just so you know.

- Speaker agreement form. This includes permission for use of your image in pre-talk announcements, as well as miscellaneous photographs, audio, and video taping. Of course it needs a signature — one of many documents in this bundle that needs a signature, even though all this stuff flies around electronically, and “e-signing” different forms presents its own form of digital torture.

- Four “board-style” multiple choice questions related to the talk material. If the course organizers are in a particularly demanding mood, they might ask you also to ensure these questions specifically linked to the dreaded Learning Objectives, see item #8. Crafting high-quality “board style” questions — with one right answer, and plausible alternatives — is particularly challenging, time consuming, and painful. Reminder: “Good enough but completed” wins here every time over “Excellent but time consuming”.

I realize that these requests are not the fault of the conference organizers or education coordinators — they are responding to requirements issued by others, usually medical schools or accreditors. Anyone who runs a post-graduate course feels this pressure, including me.

But wow, is it ever a disincentive to teach.

OK, I’ve complained enough. Now it’s time for a solution to this quagmire.

How about this approach, which was taken by a very kind person who invited me to give a lecture earlier this year?

Hi Dr. Sax, hope you’re well. We’re planning our annual conference this year, and would be delighted if you would be one of our speakers on [insert ID topic here]. Don’t worry about paperwork — we’ll take care of it — just provide us the talk title and a list of your financial disclosures, if any. We’ll also send you some proposed learning objectives for your review and approval a few weeks before the conference.

Thank you for considering!

Ellen

And thank you, Ellen, for making it so easy! And for the record, your email was light as a feather.

July 1st, 2022

Fellowship Transition and Developing a Sense of Belonging

Always a good time for a cute puppy picture.

It’s July 1, which means that today, or sometime very soon, many internal medicine residents will transition to becoming subspecialty fellows.

There are many appropriate words to describe this change, including exciting, nerve-wracking, and challenging, but one that doesn’t get quite enough attention is how strangely lonely it feels. The reason this sensation occurs is because medical residencies — through their size, structure, and voluminous shared experiences — engender a powerful sense of belonging. The bonds between you and your co-residents are strong indeed, especially after three years together.

Fellowships can’t instantly create this comforting feeling. Your fellowship group is smaller. You typically work alone, with an attending, and not as part of a team. Plus, there’s the disquieting experience of having mastered something (the bread and butter of inpatient clinical medicine), only now to be plunged into the uncertainties of a specialty that you haven’t yet learned.

How many incoming ID fellows are more comfortable managing chest pain than postpartum fever? I’d estimate it’s 100%.

If one adds to these factors the geographic relocation that may occur, it’s not surprising that subspecialty fellows take some time to feel really part of their new tribe.

Proof that the bonding of medical residency takes time to wear off is that most fellows spend the first part of their fellowship using the word “we” to describe their residency group, not their fellowship.

Here’s a smattering of select phrases that might be heard during the first few months of ID fellowship:

We used ceftriaxone and doxycycline, not azithromycin.

We would do the thoracentesis ourselves.

We don’t use procalcitonin, it’s not reliable.

And of course, the classic (and inevitable):

We would never consult ID on a case like this.

I completely get it and went through the same thing as a first-year fellow. I distinctly remember telling an inpatient medical team that their choice of antibiotics for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was wrong — because “we” did it differently during my residency. A residency done at a different hospital, of course.

(For the record, it wasn’t wrong. It was just different.)

So to those of you making this transition, we (meaning the ID community) totally understand how you’re feeling. We want you to feel welcome and part of our ID world. It might take a little time, but you’ll get there.

Pretty soon, you’ll start saying “we”, and when you do, you’ll mean you and other ID docs like you. I promise.

Welcome to the club.

June 21st, 2022

Mayo Clinic Study on Paxlovid Outcomes is Reassuring — but Likely Underestimates Rebound Rate

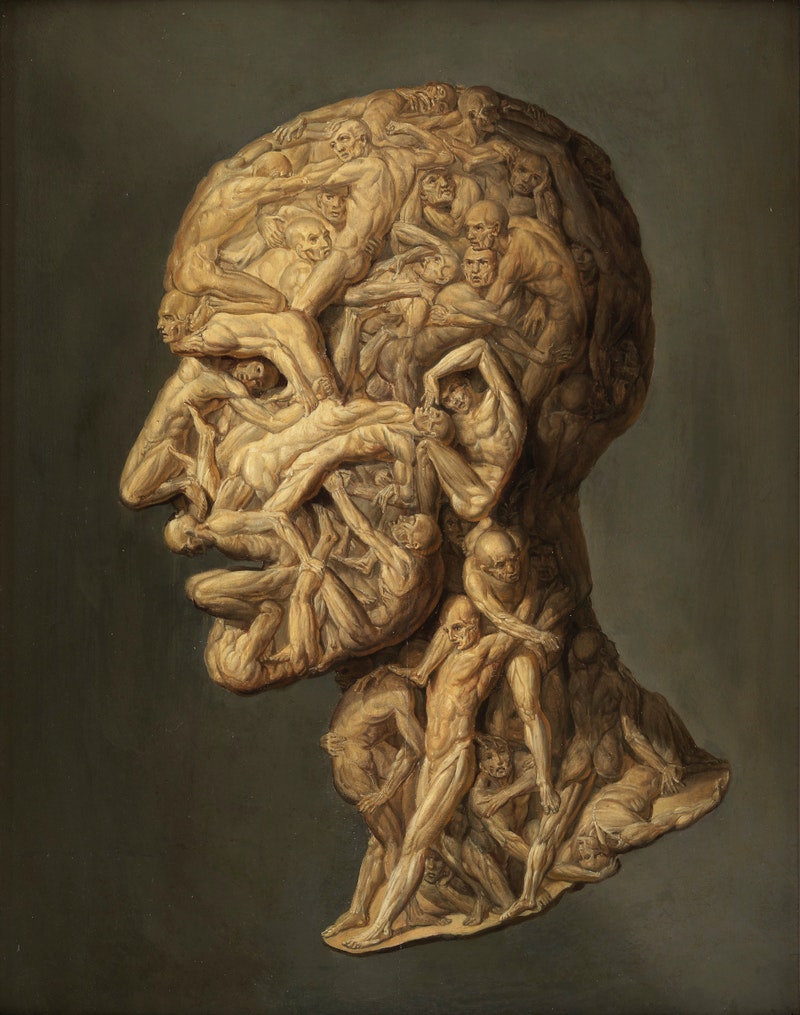

Filippo Balbi, Testa Anatomica, 1854.

Over at Clinical Infectious Diseases, researchers from the Mayo Clinic published a retrospective analysis of nirmatrelvir/r (Paxlovid) treatment, with a careful review of each patient’s chart.

The goal was to determine the clinical outcomes after the 5-day treatment course, with a focus on the frequency of rebounds — a topic of great clinical interest but with little real-world data with a decent-sized denominator.

The study included 483 patients with at least some risk factors for severe COVID-19 based on the institution’s Monoclonal Antibody Screening Score. Adjudication of eligibility was done centrally through the hospital’s COVID-19 outpatient treatment program. The mean age was 63, and 93% were vaccinated. Patients were given the option of telemedicine follow-up and encouraged to self-report symptoms or other problems; this information and their full electronic medical records were reviewed after the treatment.

Out of this group, 4 (0.8%) clearly experienced clinical rebound — these cases are described. None of the 4 received re-treatment or were hospitalized. Two other patients (neither of them rebounders) did require hospitalization, but the authors note these were unrelated to COVID-19. There were no deaths.

We can be reassured by the information on the low rate of severe outcomes, an outcome mirrored in low hospitalization rates nationally despite lots of ongoing cases. Rates of hospitalization for each COVID-19 case are now extremely low, especially among those vaccinated, and observational studies (peer-reviewed and published and unpublished) suggest that Paxlovid may reduce this risk even further. A large retrospective study from Kaiser Permanente Southern California involving 5,287 patients found similarly low hospitalization rates.

(Note that these observational studies include patient populations treated with Paxlovid with established risk factors for COVID-19 adverse outcomes — that’s how it’s mostly prescribed under the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). By contrast, those enrolled in the EPIC-SR study, which was recently stopped due to futility, were “standard risk”. Critically important will be information on baseline characteristics in EPIC-SR.)

For the Mayo study, the authors are to be credited for collecting and reporting the data so quickly, especially at a time when clinicians and patients increasingly observe the rebound phenomenon and wonder what to do about it. The centralized program used for distributing COVID-19 treatments is an additional strength of this report, as it allowed participants the opportunity to self-report progression of symptoms, and upfront ensured that all who were treated met the criteria for high risk based on the EUA.

The big limitation of this Mayo study, however, is that it’s retrospective. As a result, I strongly suspect the 0.8% rate of rebound substantially underestimates the true incidence. Pfizer reported rebounds in 2% of study participants in the prospective EPIC-HR trial, a rate more than twice as high. Based on anecdotal experience — there’s lots of Paxlovid treatment out there! — I would not be surprised if it’s at least 10 times this high, or in the 5-10% range.

What still remains unknown, frustratingly, is whether treatment with subsequent rebound reduces — or paradoxically increases — the total amount of time that people are contagious, or, if the total time is the same, does it just delay the time that a person can confidently say that they’re in the clear?

Why is this important? I’ve had people tell me that they don’t want to take the drug because they’ve heard it might lengthen the time they’re contagious. And I’ve had other patients who experienced rebound express regret on having taken the drug — even though we have no idea whether they would have tested positive for a prolonged period even without the treatment.

Let’s hope further data from prospective studies give us some answers — in particular, the placebo-controlled trials, either Pfizer’s two studies or the large PANORAMIC trial done in the United Kingdom.

In the meantime, I’m still advising people at higher risk for COVID-19 adverse outcomes — even if vaccinated — to be treated with Paxlovid, uncertainties about the above issues notwithstanding.