An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

August 18th, 2023

My Vote for the Weirdest Antibiotic on the Planet

Textile Dyeing Machine, 19th Century.

If you’re an ID doctor, there’s an excellent chance you’ve treated patients who have non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) with clofazimine. In fact, based on a poll done with the utmost scientific rigor, it’s well more than half of you.

And if you’re not an ID doctor, there’s a decent chance you’ve never even heard of it — clofazi-what? This is hardly surprising, since it gets my vote as the weirdest antibiotic out there. Of all the drugs we use in ID, clofazimine has the highest ratio of strange qualities to proven usefulness. Plus, it’s fun to say.

Allow me to share why it’s so unusual.

It’s been around a long time.

First synthesized in 1954, it initially held promise as an anti-TB agent, but it didn’t work very well. Later observations found that it was useful for treating leprosy, which is what led to FDA approval in 1969, under the brand name Lamprene. I don’t imagine there was much of a direct-to-consumer marketing effort when this blockbuster was released.

Since in vitro testing also suggested activity against non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) — for which treatment options have always been limited — ID clinicians regularly used clofazimine for years, including both for disseminated M. avium complex (MAC) disease in patients with advanced HIV disease and for pulmonary disease from NTM in immunocompetent hosts.

My first prescriptions for clofazimine were written in the early 1990s for both of these indications. I felt like I’d really arrived in exotic ID Land, writing for this strange drug used for leprosy. Wow.

Despite its approval over a half-century ago, you can’t just prescribe it anymore.

For reasons likely having to do with profit (or the lack thereof), in 2004 the drug disappeared from pharmacies. But it remained an essential drug for the treatment of leprosy in government-funded programs, so the company (Novartis) continued to manufacture it on a limited basis for this indication only.

This put us non-leprosy clofazimine prescribers in a bind. Azithromycin and clarithromycin had come along, greatly improving outcomes for treatment of these difficult bugs. But some MAC isolates and many strains of M. abscessus have macrolide resistance.

Certain enterprising patients heard the drug was still available in Canada (I wonder who told them … hmmm), but that door closed too.

But clofazimine remains widely available in many countries with high TB incidence. One colleague told me it can be purchased in India in most pharmacies for “cents”. It really is striking how often mycobacterial diagnostics and therapies are often more accessible in resource-limited countries than here.

But you can still get it here — warning, the process is not for the paperwork-averse.

Initially, the National Hansen’s Foundation distributed clofazimine on a very limited basis using what’s called a single patient investigational new drug (SPIND) program overseen by the FDA. That changed in 2018, and now Novartis runs this program.

These expanded access programs are in reality clinical research studies — enough so that the clofazimine program appears on clinicaltrials.gov, and approval will be required by a local Institutional Review Board (IRB). That clinicaltrials.gov link contains the critical information about how to get started, which is to email or call the company stating you have a patient who needs clofazimine. They will follow up with a series of essential steps before you can get the drug for your patient — here’s an (old) summary that’s no longer quite accurate but captures the basics.

You certainly won’t find this information on the Novartis site, or at least I couldn’t. Maybe it’s there somewhere.

What’s it like to go through this clofazimine approval process? As the site principal investigator for this program at our hospital, I can attest that Dr. Joseph Marcus provides here a highly illustrative video:

Did a SPIND for one pt at my institution as a first year attending and coordinating everything felt like a final exam/obstacle course of everything I learned in fellowship pic.twitter.com/H1Wc38cr3d

— Joseph Marcus (@JosephMarcusID) July 20, 2023

Hey, there’s a reason why we’re the Paperwork Champs! If it weren’t for the help of our research pharmacy and regulatory coordinator (thank you, Maria and ID pharmacy team!), I never could do this in a million years.

The drug looks active in vitro, but we really don’t know if it works.

Some reference labs will run clofazimine susceptibility testing on NTM isolates and report minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), but also add cautionary comments about the lack of standardized MIC breakpoints. In other words, lower MIC numbers seem better — and the results usually are low — but we really don’t know how this correlates with the drug’s clinical activity.

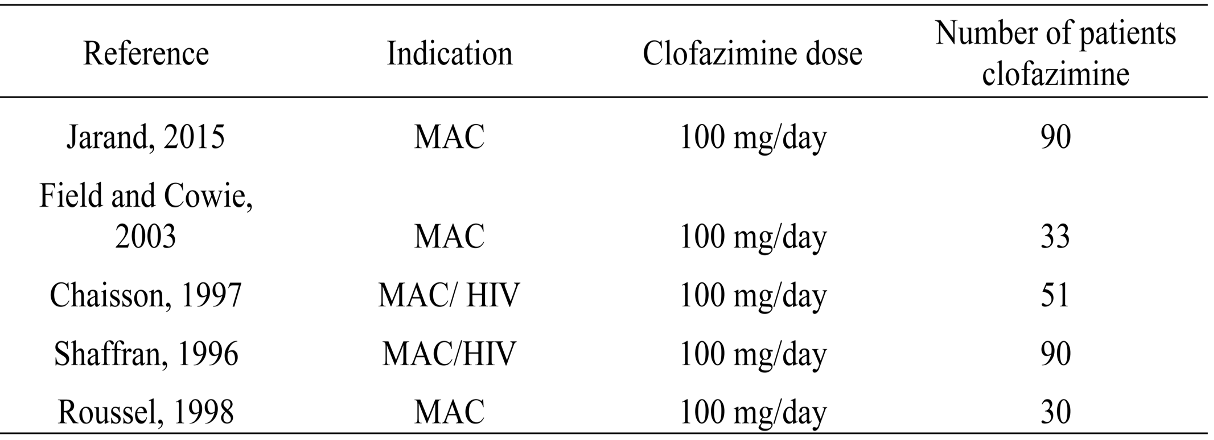

In addition, prospective data on clofazimine treatment in humans are incredibly sparse — and that’s being generous. From an informational slide set provided by Novartis comes this summary table:

The first study on this slide gives us probably the strongest favorable data — not only does it have only 90 treated patients, but it’s also not randomized and retrospective.

The slide also includes this statement:

No properly designed randomized controlled trials (RCT) have been reported to evaluate the role of clofazimine in the treatment of NTM infections.

Agree 100%. And while there are numerous other published studies besides those on this table, most are case series, not comparative clinical trials.

One possible reason for the lack of good data is the heterogeneity of people who have NTM pulmonary infection, ranging from asymptomatic colonization to progressive, life-threatening disease. Plus there are hundreds of different NTMs, and they can infect other sites, not just the lung.

As a result, this is a very challenging disease to study prospectively. One ongoing clofazimine treatment study opened in 2016; it has a sample size of 102. It still has not been completed.

The end result of this knowledge gap on the efficacy of clofazimine was succinctly put by Dr. Cam Wolf, who wrote:

For these infections, it’s nigh on impossible to tell if clofazimine is the difference maker.

Yep.

But this might change soon. There are other ongoing clinical trials of the drug, with the caveat that most of them involve tuberculosis, not the NTM we more often treat here.

Two randomized clinical trials of clofazimine for MAC in HIV found that clofazimine-treated participants had a higher mortality rate.

In people with advanced HIV disease and disseminated MAC, treatment with clarithromycin, ethambutol, and clofazimine was compared to clarithromycin and ethambutol alone. Mortality was 61% in the clofazimine three-drug group versus 38% in the two-drug group.

(Reminder, the pre-ART era in HIV was grim — and tragic.)

Baseline differences between the two groups, with higher levels of infection in the clofazimine recipients, could explain these unfortunate results — but it also could have been an adverse effect of clofazimine, which has in vitro anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects on both T-cells and monocytes/neutrophils. Could that explain the negative results in this highly immunocompromised group?

A second study in a similar population compared a three-drug macrolide-containing treatment with a four-drug non-macrolide regimen with clofazimine; survival was longer in the former. In this trial, it’s hard to blame the clofazimine, since only the three-drug group received a macrolide, the most active drug for MAC.

Limitations in these studies notwithstanding, we nonetheless generally avoid clofazimine in these very sick people with HIV.

How these discouraging study results inform the proper use of clofazimine in most patients with NTM infection treated today is anyone’s guess. Your typical pulmonary NTM infection case — not immunosuppressed, no dissemination — is worlds away from a person bacteremic with MAC, untreated HIV, and a CD4 cell count <50.

Still, it’s a concern.

We don’t know how it works.

That is, if it works.

But let’s assume it does. The two most commonly cited mechanisms are redox cycling and membrane destabilization and dysfunction. Not particularly strong in either biochemistry or molecular biology, I will share this erudite summary of the latter hypothesis from an excellent review:

This contention is based on the study by Baciu et al., who reported that cationic amphiphiles such as clofazimine partition rapidly to the polar–apolar region of the membrane, where, at physiological pH, the protonated groups on the drug catalyse the acid hydrolysis of the ester linkage of the phospholipid chains. The consequence is the production of a fatty acid and a lysophospholipid, both of which possess antimicrobial activity.

Those are sentences I never could have written. Fortunately, one doesn’t have to understand the mechanism of an antibiotic to use it.

Clofazimine has one common and very strange side effect — and a few others that are less common but very important.

The most famous side effect — or infamous, if you don’t like it — is skin darkening. It occurs in most people, is exposure-related, gradual in onset, and takes on a variety of different hues, from barely noticeable to quite dramatic.

For some, it’s quite flattering, if emulating sun exposure is the desired effect. “My friends all ask me where I’ve been this winter for my suntan,” said one of my patients, as Boston’s winter rays could never produce that warm glow. She likes it.

But for others, it just looks … strange. Watch out if you combine clofazimine with omadacycline (as we increasingly do with treatment of M. abscessus), and add a dose of strong summer sunshine. Covering arms and legs and wearing a broad-brimmed hat are both highly recommended! Fortunately, the skin darkening slowly wears off after the clofazimine is stopped.

Note that the darkening can occur in mucosa, conjunctiva, and body fluids too. Other skin side effects are excessive dryness and generalized pruritus. These dermatologic side effects could be one motivator behind the ongoing study of inhaled clofazimine, which presumably would avoid this toxicity.

Cases of torsades de pointes due to QT prolongation have been reported, as well as a serious syndrome of crystal deposition in intestinal mucosa, the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. Suspect this crystal deposition problem if a patient on clofazimine develops worsening abdominal pain, and stop the drug immediately. Both the QT prolongation and the crystal deposition are more likely with higher doses.

So there you have it: clofazimine in all it’s extraordinary weirdness, hope I’ve convinced you.

Let’s hope we get some more data on the safety and efficacy of this drug sometime soon — and, if the results are favorable, the hurdles to using it finally come down. Our patients with NTM infection need all the help they can get!

Thanks for this mini-treatise on a very interesting antibiotic that I will most likely never have reason to prescribe. I wonder if the original manufacturer realized that the name Lamprene is kinda close to “lamprey”. The visual image I immediately got when I saw “Lamprene” was of a lamprey! So there, that’s why the drug wasn’t marketed successfully. 🙂

I remember having used clofazimine in the (distant) past for recalcitrant pyoderma gangrenosum. It was helpful but never seemed to take the patient over the finish line.

I remember using clofazimine in the early 90’s for my DMAC patients back in the sad days. They turned a battleship gray.

Another lighthearted, beautifully written, informative article.

Thanks for continuing this blog.

Yes, those were grim days.

Thanks for reading all these years, Gordon!

-Paul

Clofazimine is used fairly often in treatment of drug-resistant TB globally, but even in this infection the data is really weak. Wonder if we’ll be using it at all in a decade for anything.

Very Interesting and so are all the comments.

I am an Infectious disease specialist who has Ashy dermatitis, also known as erythema chronicum perstans. I have tried many treatments, pioglitazons , dapsone , hydroxychloroqine. I am afraid using clofazimine would affects my corneal transplants. It’s odd that it should treat my ashy grey face yet it’s side effect is grey pigmemr

The most cumbersome process of my entire career. I finally gave up and referred to the university hospital down the road!

https://formattrial.com/

https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04310930?cond=mycobacterium+abscessus&draw=2&rank=8

Thanks Paul, the FORMat trial for Mycobacterium abscessus is an adaptive platform study currently recruiting. One of the questions it will answer is whether the addition of clofazimine in the intensive phase improves outcomes and also looks at tolerability.

In addition to the many strange things Paul describes (and I agree entirely; the paperwork is a nightmare), it comes in the strangest packaging for a pill. When I started prescribing it, Novartis would not ship it to me, but to a different hospital in my system. So I asked my office-mate, who worked at both facilities, to pick it up for me. The next day, he showed up struggling with a gigantic box, which contained a little bottle of pills and a temperature monitor surrounded by multiple layers of ice packs and insulation. I had to download the temperature data to verify the cold chain. This may not be a bad idea, since they ship it from Texas, but it seemed like overkill. I apologized to my colleague for making him my drug mule.

Hi Paul,

Enjoyed that account. Of course, in my neck of the woods in Mumbai, that global epicentre for MDR-TB, Clofazamine is very commonly used in most MDR regimens and is considered an invaluable second line drug. Cross resistance with Bedaqualine is a huge concern.

Just saw this the other day in the ED (pt was on therapy, not initiated in the ED – EM is the antithesis of paperwork champs but that’s ok!) Still waiting for a pseudo-med spa/boutique to prescribe as a “safe alternative” to tanning beds!

With clofazimine’s widespread use in MDR-TB patients, there has been new data on its efficacy (although with TB) and safety, particularly among people living with HIV.

Beside the use of clofazimine for MAC and lepra it is also used in dermatology for cheilitis granulomatosa (orofacial granulomatosis) as an off label treatment with moderate success. The data is also very weak!

Thank you Paul for your comments on Clofazimine and for your sense of humor.

My first contact with clofazimine was for the treatment of MDR TB. At that time, developing an effective regimen entailed high toxicity, especially due to aminoglycosides. I also did not know its mechanism of action but CFZ worked and allowed to shorten

the duration of aminoglycosides. Currently we use it mainly for pulmonary infections by M abscessus.

I used it for a prosthetic joint infection with a NTM and the patient ended up with terrible lymphoedema – worse on the infected side and mild lymphoedema contralaterally. Apparently symmetrical lymphoedema is a known side-effect but not one I had ever been aware of. His PJI was cured though!

Treatment of Mycobacterium avium complex infection: do the results of in vitro susceptibility tests predict therapeutic outcome in humans?

Sison JP, Yao Y, Kemper CA, Hamilton JR, Brummer E, Stevens DA, Deresinski SC.J Infect Dis. 1996 Mar;173(3):677-83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.677.PMID: 8627032

Administration of clofazimine alone for one month to HIV patients with MAC bacteremia failed to reduce bacteremia monitored quantitatively.

Please add my e-mail address to your mailing list. Thank you.

Jeffrey Stall MD