An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 7th, 2013

CD4 Cell Count at Presentation: A Figure with a Depressingly Small Upward Slope

You know how to make an ID/HIV specialist angry? Frustrated? Sigh loudly?

You know how to make an ID/HIV specialist angry? Frustrated? Sigh loudly?

Tell a clinical anecdote that involves “late” presentation of HIV diagnosis, in particular someone who has been seeking medical care for various ailments for months or even years without getting tested.

You know — it goes something like this:

“He was seen 3 years ago for zoster [or syphilis or pneumonia or thrombocytopenia], and no one sent an HIV test. Now he’s in the hospital with PCP and 10 T-cells.”

It makes smoke come out of our ears because first, it’s so preventable, and second, it doesn’t seem like we’re making any progress.

Well, that’s not quite true — we are making some progress, just not very much. In Clinical Infectious Diseases, a new paper summarizes the trend in CD4 cell count at diagnosis for nearly 170,000 patients in studies published from 1992 to 2011. Here’s the punch line:

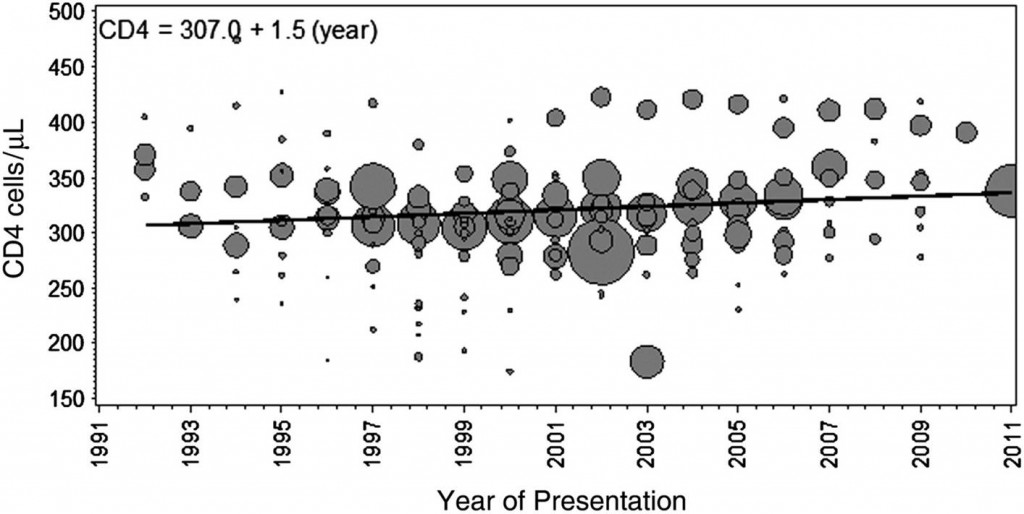

Mean CD4 cell count at presentation increased minimally by 1.5 cells/μL per year (95% CI, −6.1 to 5.5 cells/μL per year), from 307 cells/μL in 1992 to 336 cells/μL in 2011.

Yes, folks, that’s a 1.5 cell/year increase! Got to show the figure, which no doubt will be much-cited, with considerable hand-wringing:

Note in particular the lack of inflection in the late 1990s — you know, the years when HIV became treatable.

As the authors note, these findings raise significant questions about the “treatment as prevention” strategy, at least if the goal is complete elimination of the HIV epidemic. They also make many of our “when to start” debates completely irrelevant for more than half the newly diagnosed patients — their CD4 is already < 350, often substantially so.

The legal impediments to HIV testing are now pretty much gone, thank goodness. So what is the reason for this continued delay in diagnosis?

The theory that the natural of course of HIV infection is marked by a normal CD4 count followed by a slow decline was never correct. This is based on outdated data that chose to follow healthy subjects in the era of thousands of others who were sick and dying, omitted from these studies and probably recently infected as well. For those of us who see new patients every week with CD4 counts in the 300s, we know that many can prove recent negative HIV status. Let us get away from the 1980s/90s model of a slowly declining CD4 count as characterized by a population confounded by having no symptoms and consider that most people do not maintain a normal count once they are infected.

Hi NY HIV MD,

Agree entirely that many people who are newly infected don’t have normal counts (and certainly don’t have normal CD4/CD8 ratios). But there is of course a wide range around a median, and the data support a median of over 600 right after seroconversion.

J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003 Sep 1;34(1):76-83.

Differences in CD4 cell counts at seroconversion and decline among 5739 HIV-1-infected individuals with well-estimated dates of seroconversion.

CASCADE Collaboration.

Paul

Hi, Dr. Sax. Your last Journal Watch about the modest (depressingly) increase of the CD4 Count at presentation is very interesting and worrying. In relation to this, I would like to say that a lot of time ago some clinicians were already worried by the problem of a late medical care to HIV patients. Two previous Spanish papers (letters to the Editor) called the attention about this issue. In the first letter, published ¡in 1994! (Muñoz Sanz A et al. Asistencia médica tardía a los pacientes infectados por el VIH. [English translation: Late medical assistance to HIV-infected patients]. Med Clin (Barc) 1994), the authors shows that 53,8% of their patients were attended after the CD4 count was lesser than 500; also, 28,44% presented with a CD4 count lesser than 200 cells/ml. Twelve years after (2006), the situation was no better. In that year (a decade after the beginning of the triple and active combination therapy/HAART), the data were still worst: 65,9% (<500 CD4) and 26,1% (<200 CD4), respectively (Muñoz Sanz A. El tratamiento antirretroviral tardío y su efímera eficacia. [English translation: Late antiretroviral therapy and ephemeral efficacy] Med Clin [Barc] 2006; 127: 237). As the author of the last paper said, this is a good example of LART (Late AntiRetroviral Treatment). So, the HAART appearance 17 years ago can remember us the arrival of man to the Moon in 1969 and the famous quote of Neil Amstrong. With the feet on the ground, we can now state that HAART is one big step for an individual patient, but a small leap for the total HIV community (because the start is late).