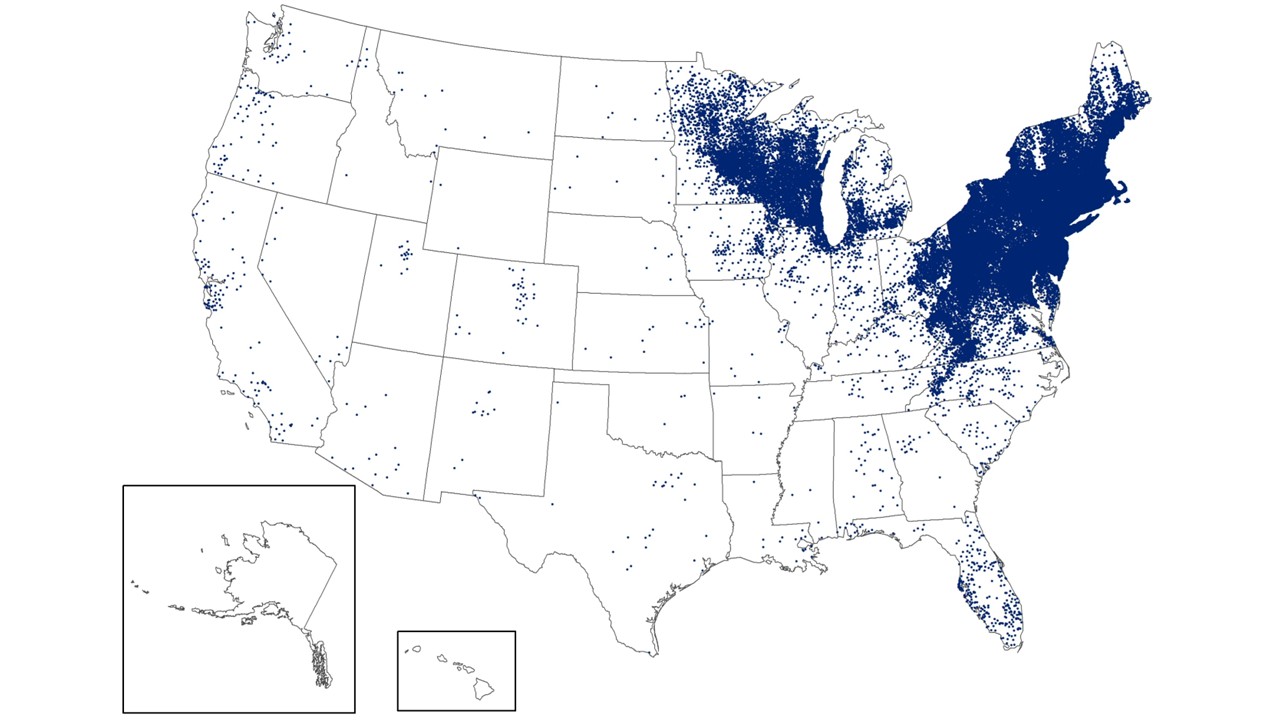

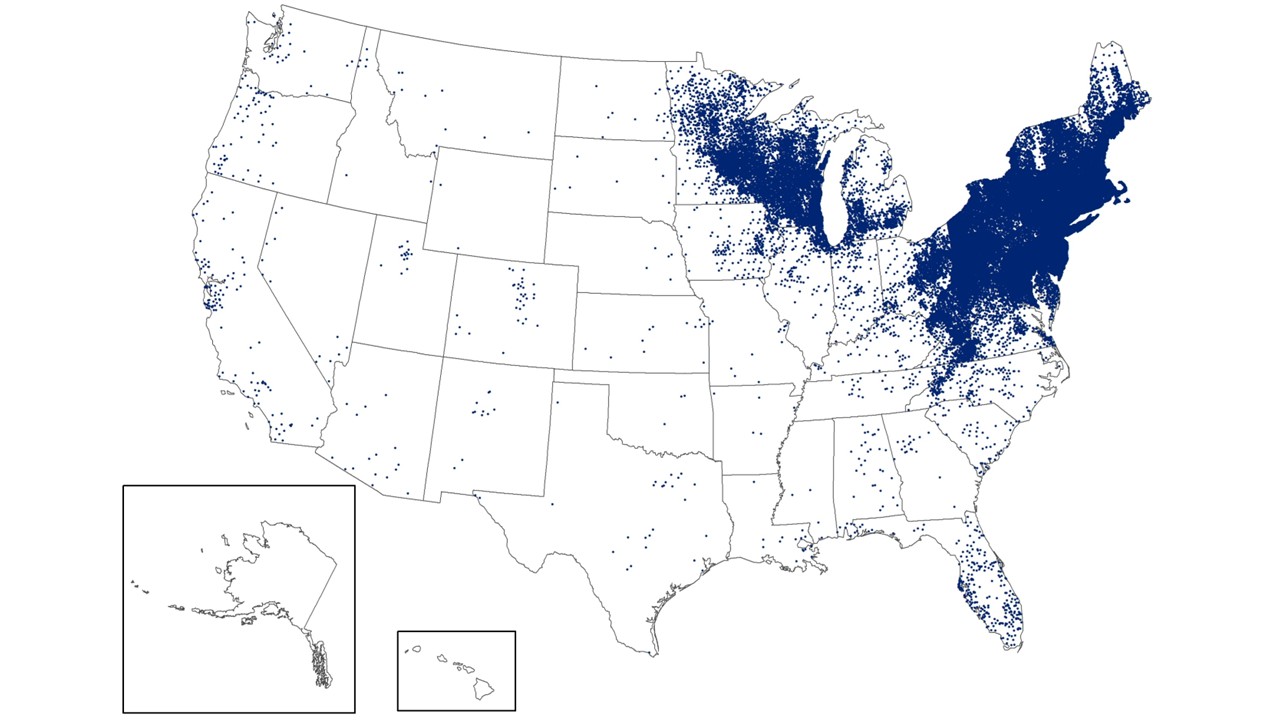

Lyme disease cases, 2023 (CDC). Each dot represents a new reported case.

Just back from a visit to the Infectious Diseases Division at Johns Hopkins, thanks to the kind invitation of current ID chief Dr. Amita Gupta and her predecessor, Dr. David Thomas.

On a personal note, this visit was only a few decades late. When I applied to medical school, Hopkins never invited me to interview — an awkward omission since my father’s family is from Baltimore, and my aunt had generously offered to host me when I was “interviewing at Hopkins.”

Oops.

That said, all is forgiven. They could not have been more welcoming this time around. In a busy day spent mostly chatting with ID faculty, a highlight was sitting down to lunch with their current ID fellows — and not just because of that delicious lunch.

I asked them a simple question: What are your favorite ID consults? I already know the greatest hits from our Harvard ID fellows; would responses from another academic powerhouse be similar?

Here’s what they said:

“Patient coughed up a worm.”

A perennial crowd-pleaser, sure to bring gasps of delight when the consult question pops up on the beeper. (We ID doctors are weird.) In hospitalized patients, this is most likely Ascaris lumbricoides — typically when adult worms migrate from the gastrointestinal tract into the respiratory tract, sometimes triggered by anesthesia in patients with a heavy worm burden. Treatment is a single dose of albendazole or mebendazole. And no, they do not require respiratory (or other) precautions.

Fever of unknown origin in a previously healthy person.

Don’t confuse this with fever of “unknown” origin in a patient who has been in the ICU after surgical complications that occurred shortly after Memorial Day, with today being hospital day #160. That’s actually a Fever of Too Many Origins (FOTMO), as brilliantly described by Dr. Harold Horowitz in his classic NEJM piece. (Required reading for all ID docs.) By contrast, true FUO in a previously well patient remains one of the most challenging and intellectually satisfying puzzles in medicine.

Tick-bite infections.

Always gratifying — especially when it’s anaplasmosis and the patient shows that magical overnight response to doxycycline. And in case anyone in New England feels that we have the privilege to be uniquely obsessed with these critters, a glance at the Lyme map shows the mid-Atlantic states are similarly stricken. It’s no wonder long-time Hopkins faculty member Dr. Paul Auwaerter is a lead researcher in the phase 3 Lyme vaccine clinical trial — we eagerly await results!

Exposure history that sounds like a parody of an exposure history.

An example they offered: A patient from rural Maryland lives on a farm, processes their farm’s poultry on-site in a mobile unit, and works long days in fields and buildings teeming with insects and rodents. Oh, and last week they cleaned out a chicken coop with a leaf blower without wearing respiratory protection. Now, they’re admitted with fever, cough, and pneumonia. You know, your typical ID board certification question, only real life. (For non-medical readers out there, this could be anything — viral, bacterial, fungal, allergic.)

A case right in your ID attending’s wheelhouse.

Imagine the fellow is on service with a world-famous expert in syphilis. A consult comes in for a patient with eye pain, redness, photophobia, and blurred vision; the ophthalmologist has already diagnosed pan-uveitis. The history reveals many high-risk sexual exposures and prior bacterial STIs. You can be sure the attending will be thrilled to deliver a state-of-the-art lecture on syphilitic ocular disease, ready for publication as a review article, references already formatted.

The mystery culture nobody recognizes.

The microbiology lab reports a result that sounds vaguely extraterrestrial, and the primary team panics. Enter ID: “Oh — that’s really just Old Familiar Bug X, renamed Y thanks to the NGS/MALDI-TOF revolution.” Diagnosis: MALDI-TOF-itis*! Treatment: reassurance and something sensible. (*Am I the first person to coin that term? If so, I claim patent rights.)

Fever in a returning traveler.

One of the great ID pleasures: The vicarious thrill of taking a highly detailed travel history. Where did they go? When? What did they eat? Swim in? Where did they sleep? (And with whom, ahem.) Sure, malaria must always be ruled out, but we quietly delight in the diagnostic breadth: dengue, chikungunya, typhoid, rickettsioses, schistosomiasis — and the occasional diagnosis you only see every five years but remember forever.

These are all great examples, and I enjoyed our conversation enormously. And full credit to them for giving me the idea for my latest blog post (this), and for that, I’m grateful enough to send along a free subscription.

And — circling back to my opening question — were their picks similar to those from the Harvard ID fellows? Absolutely. In every program, what excites trainees most is the same rich blend of detective work, unexpected biology, and quirky human detail that draws us to infectious diseases in the first place.

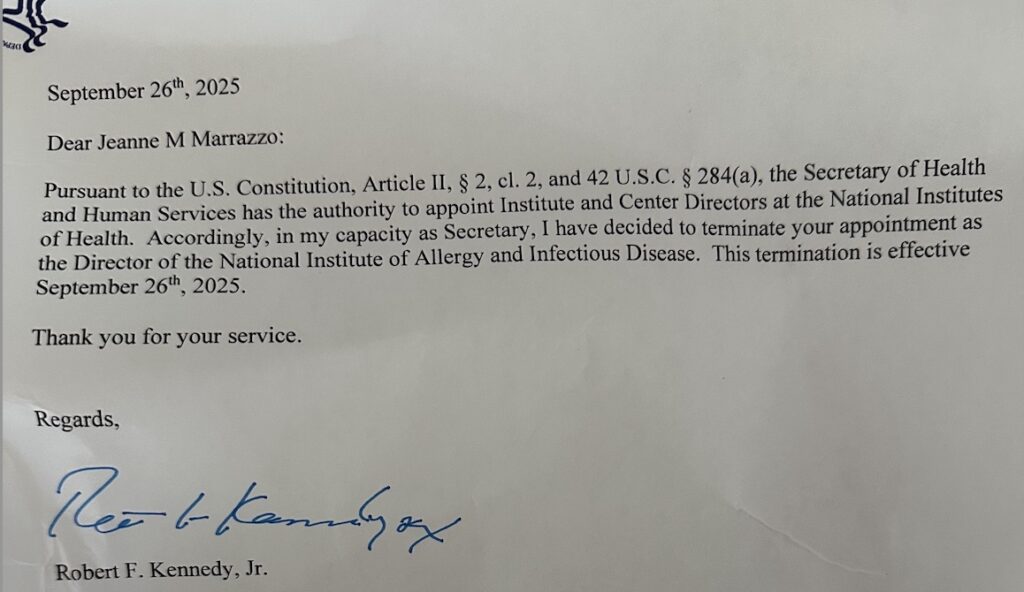

Overall, it was a terrific visit — the kind that reinvigorates your enthusiasm for our field and for the bright future embodied by the next generation, even against today’s storm clouds (about which the less said, the better).

Now, about that medical school interview …

(If you’d like a more informal take on a recent ID headline — the latest listeria outbreak — I’ve written about it on my Substack.)

As we await the results of placebo-controlled Covid-19 vaccine studies, what are we clinicians to do when our patients ask us whether they should get a booster this fall? What once was a no-brainer in the early days of limited immunity to the virus — and the

As we await the results of placebo-controlled Covid-19 vaccine studies, what are we clinicians to do when our patients ask us whether they should get a booster this fall? What once was a no-brainer in the early days of limited immunity to the virus — and the

On Friday night,

On Friday night,  The DOTS randomized clinical trial of dalbavancin versus standard-of-care for Staph aureus bacteremia (SAB)

The DOTS randomized clinical trial of dalbavancin versus standard-of-care for Staph aureus bacteremia (SAB)

Three-drug therapy has been the standard of care for HIV therapy for so long it’s difficult to shake the view that it must be more effective than two drugs. This is particularly the case for those with advanced, HIV-related immunosuppression or very high viral loads, as they provide an important stress test for all regimens.

Three-drug therapy has been the standard of care for HIV therapy for so long it’s difficult to shake the view that it must be more effective than two drugs. This is particularly the case for those with advanced, HIV-related immunosuppression or very high viral loads, as they provide an important stress test for all regimens. Like most clinicians, I have a checkered history with required online learning modules. You know the drill: click play, get lectured in monotone about hand hygiene or fire safety, then spend the next 8 minutes desperately searching for the fast-forward button, hoping it’s not disabled.

Like most clinicians, I have a checkered history with required online learning modules. You know the drill: click play, get lectured in monotone about hand hygiene or fire safety, then spend the next 8 minutes desperately searching for the fast-forward button, hoping it’s not disabled. The last time I did one of these quick “musings” posts, I listed 21, and someone asked me, “Why 21?” The answer — obviously — is that I originally planned on writing 20, but then had to add a 21st, just because that’s exactly how many points you need to win a ping pong game.

The last time I did one of these quick “musings” posts, I listed 21, and someone asked me, “Why 21?” The answer — obviously — is that I originally planned on writing 20, but then had to add a 21st, just because that’s exactly how many points you need to win a ping pong game.