Looking back on these annual Thanksgiving posts, I notice an odd pattern: every few years, the intro turns into a kind of apology. As in, Yes, I know the title sounds upbeat, please don’t attack me. The world feels heavy, the ID bad news scrolls by, and there I am writing about gratitude.

Looking back on these annual Thanksgiving posts, I notice an odd pattern: every few years, the intro turns into a kind of apology. As in, Yes, I know the title sounds upbeat, please don’t attack me. The world feels heavy, the ID bad news scrolls by, and there I am writing about gratitude.

A colleague hit the tone perfectly this week when I sent her a minor complaint over email. Her response?

Sorry. Everything sucks. Truly. But it’s my birthday tomorrow, so that’s cool. You can whine anytime.

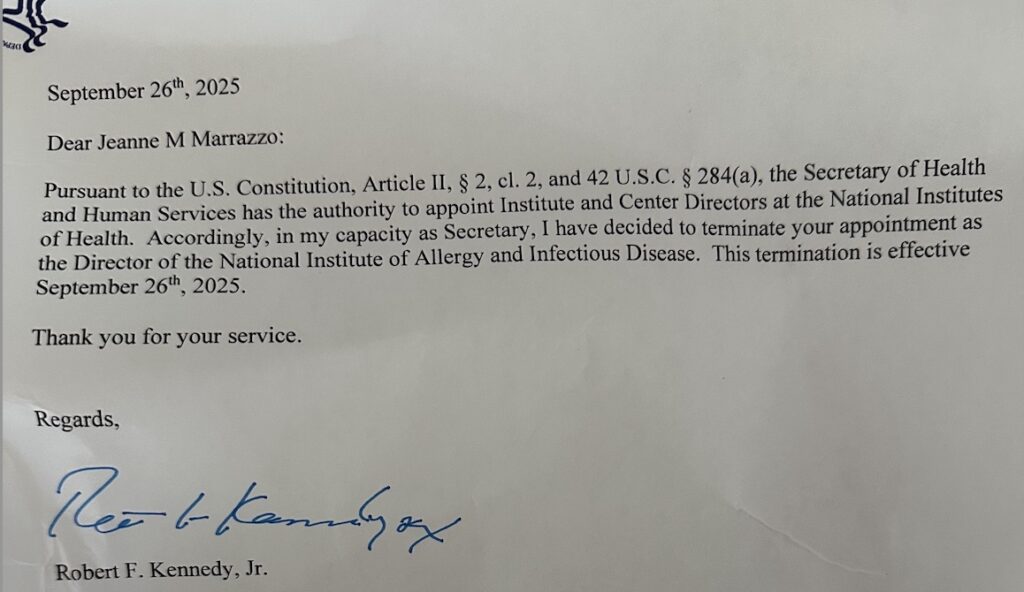

Yes, that pretty much captures 2025 — equal parts bleak and bemused and sympathetic. And yet, here we are, practicing the small but important task of noticing the good things, and that includes birthdays and ID advances. We do it even amidst the CDC’s decimation, the swelling anti-vaccine chaos, the government shutdown, the canceled global foreign aid, and all the grim funding cuts, with ID research leading the way (in a bad way).

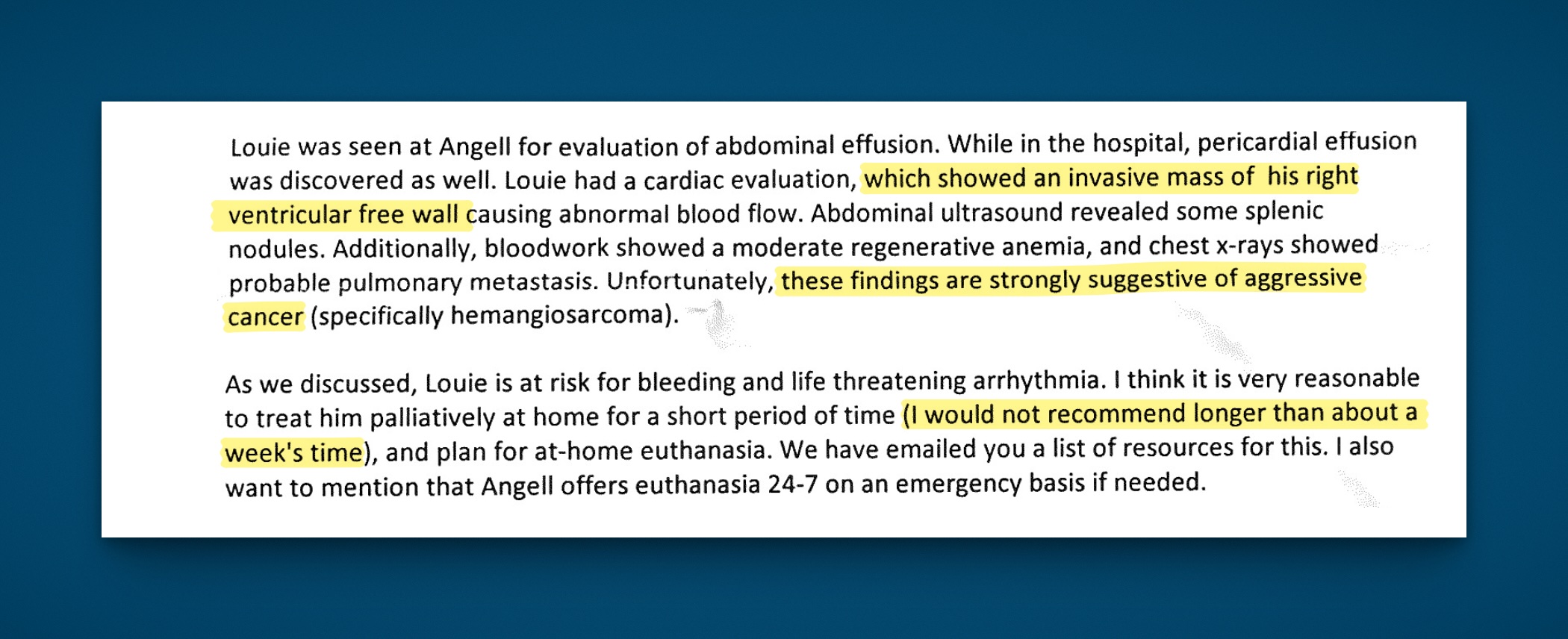

(Plus, Louie’s untimely demise. Still miss you, buddy.)

But hey, we keep going. We always do. So here we go again: A half-dozen solid ID things that happened in 2025 that we can be grateful for as we head into the holiday season.

#1: Lenacapavir Lands

In June, the FDA approved lenacapavir for HIV prevention, instantly giving PrEP a genuinely novel approach. A twice-yearly injection? It still feels a bit like science fiction; no wonder journalists mislabeled it a “vaccine”. Now it is slowly rolling out into practice, and we’ll soon see whether those astonishingly high efficacy numbers from the trials hold up in what is commonly referred to as “the real world”. (Argh, sorry to employ that overused cliche.)

Even better, there’s a deal to supply the drug in low- and middle-income countries for around $40 a year — a staggering improvement in global access. And there’s more in the works: the cleverly named PURPOSE-365 study is testing whether we can go to once-yearly lenacapavir intramuscular injections, and MK-8527 (surely overdue for a real name) is moving forward as a once-monthly oral PrEP pill for those who’d rather avoid needles entirely.

#2: For Bacterial Vaginosis, It’s Time to Treat the Male Partner Too

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is incredibly common, has several adverse associations, and frequently recurs after treatment — frustrating for both women and the clinicians who treat them. Meanwhile, partner treatment has not been recommended, despite evidence that males harbored some of the same bacterial species implicated in this condition.

Now, along comes the STEP-BV trial, which finally gave us a nicely done study looking at treating male partners. In outpatient clinics in Australia, women with BV and their male partners were randomized to either treatment of the woman only or to treatment of both partners within 1 week of each other.

And here’s the exciting news: Treating the male partner helped a lot, reducing recurrence by 50%, a difference big enough to prompt the data safety monitoring board to stop the study early. It’s not a total solution (recurrence rates were still 35% even in the treatment group), and as with all partner treatments in STIs, implementation will take some thought and involve tricky coordination. But for a condition that’s incredibly common, burdensome, stigmatized, and annoyingly relapsing, this is a big advance.

#3: SNAP Trial of Staph aureus Bacteremia Yields Its First Major Findings

The long-awaited SNAP trial — the largest randomized study ever done for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia — finally brought clarity to treatment questions that have lingered since my fellowship days. Conducted across multiple countries (notably excluding the U.S., for reasons that deserve their own rant), SNAP compared cefazolin versus flucloxacillin for methicillin-susceptible Staph aureus (MSSA) and penicillin versus flucloxacillin for penicillin-susceptible strains (PSSA).

The results were refreshingly definitive: cefazolin was noninferior for 90-day mortality and caused less kidney injury, and penicillin was not only noninferior but probably superior for PSSA, with significantly less toxicity. Yes, we really can trust modern penicillin susceptibility testing. (Time to clear that penicillin-allergy label!) After decades of debates about the “inoculum effect” and whether old-fashioned penicillin still has a role, SNAP gives us real evidence to guide care and finally puts some of these perennial controversies to rest.

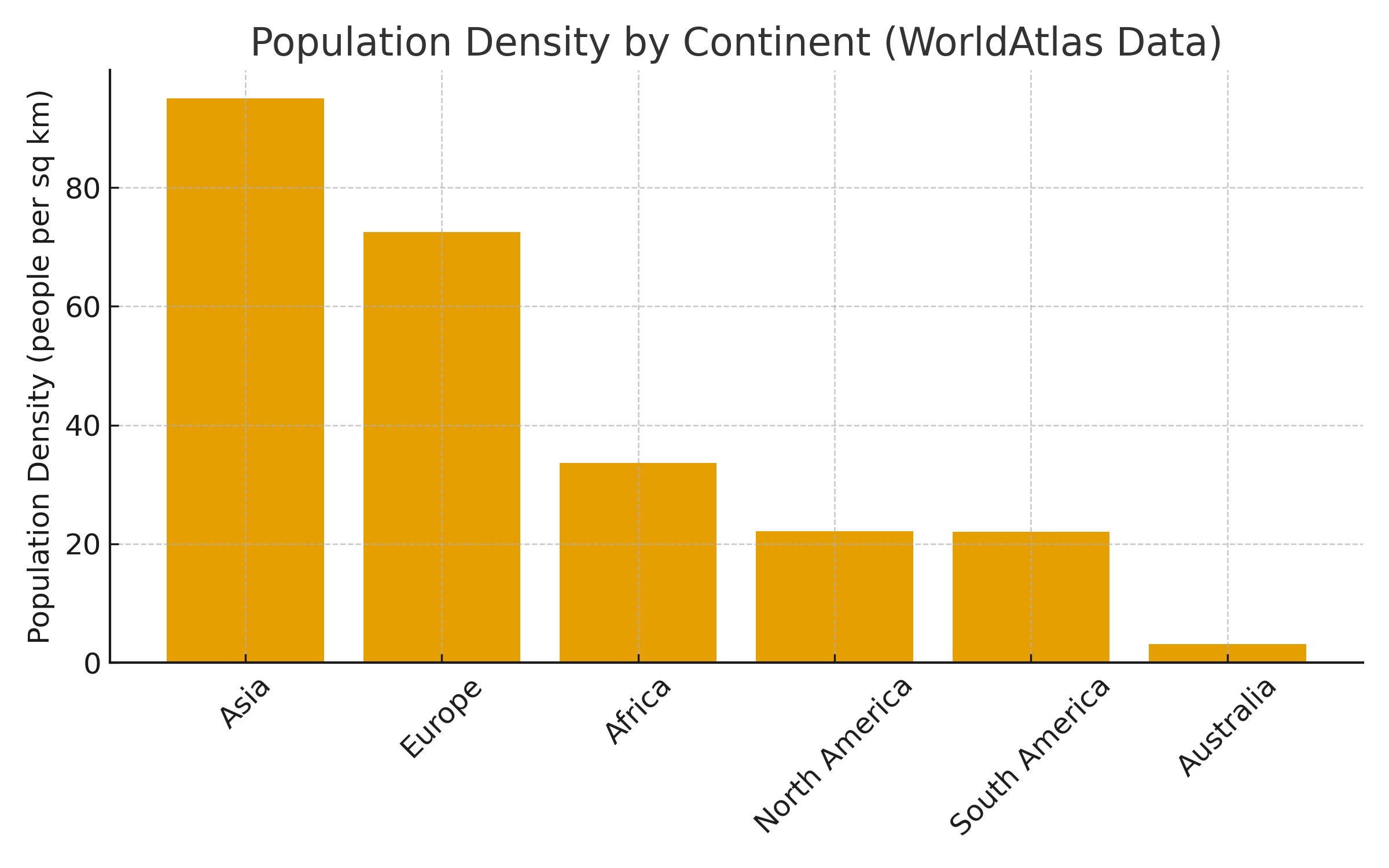

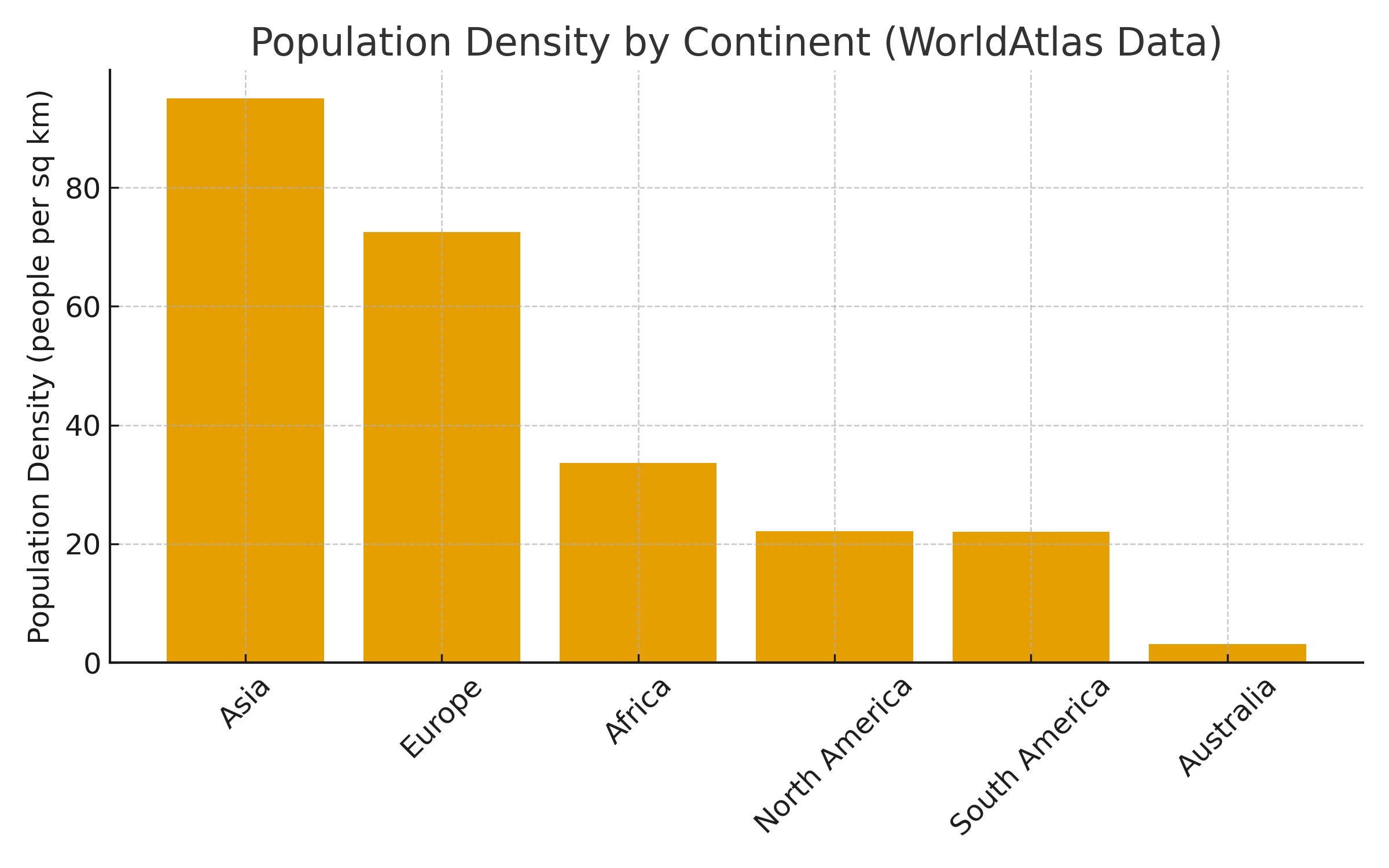

(Note that both #2 and #3 were led by investigators from Australia, a country with great ID clinical research despite the continent’s low population density. Impressive.)

#4: Dalbavancin Has Its Moment in the Spotlight

For years, dalbavancin sat behind a thick glass case in the hospital pharmacy, next to a sign that might as well have said, “If the patient has no OPAT options and their social situation makes your head hurt — break glass.”

Enter the DOTS trial, which basically told us: Yep, in patients with staph bacteremia, even without challenging discharge factors, this long-acting vancomycin-like drug works just as well as daily intravenous therapy — and it’s so much more convenient! Two doses, separated by a week! Vastly superior to having a PICC line and managing outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) for weeks.

Prediction: Based on DOTS, we’ll be seeing a lot more dalbavancin in 2026 and beyond. And honestly? That’s great news for patients and for everyone who has ever tried to arrange home IV antibiotics over a holiday weekend. Now we just need the price to come down and for people to understand that the cost of patient care is not siloed just in the pharmacy budget.

#5: Cabotegravir-Rilpivirine Expands Its Target Population

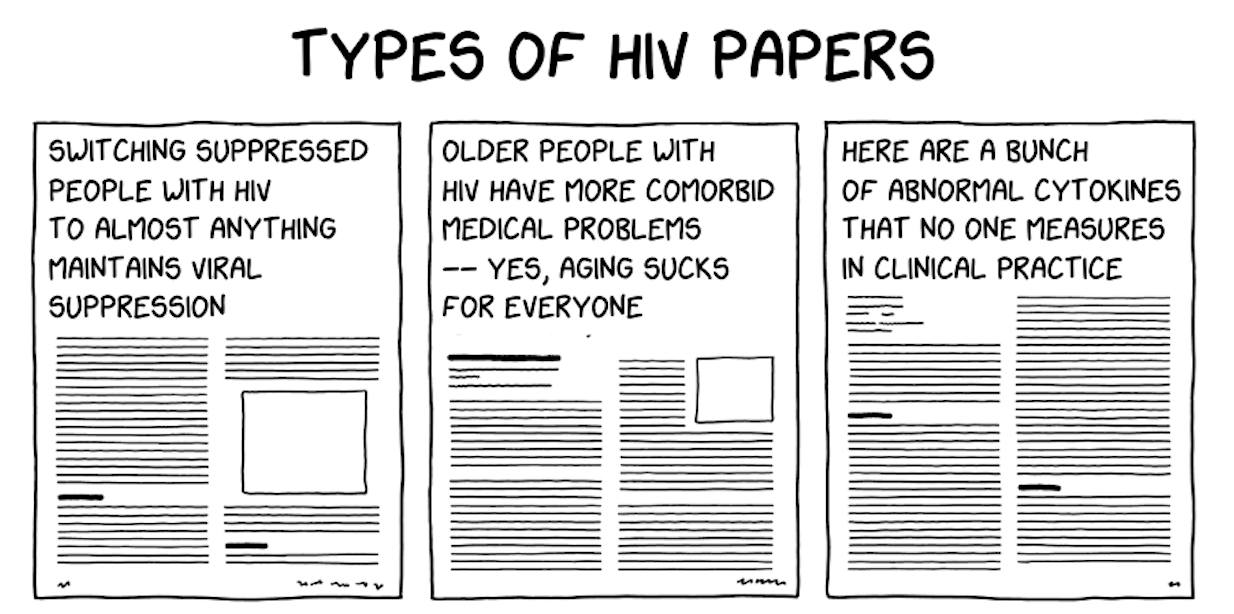

The pivotal licensing trials (ATLAS, FLAIR, ATLAS-2M) for cabotegravir-rilpivirine understandably enrolled only our most successfully treated patients — those with no prior treatment failure, no resistance, on first or second regimens. And this population has, historically, done incredibly well with just about any medication switch.

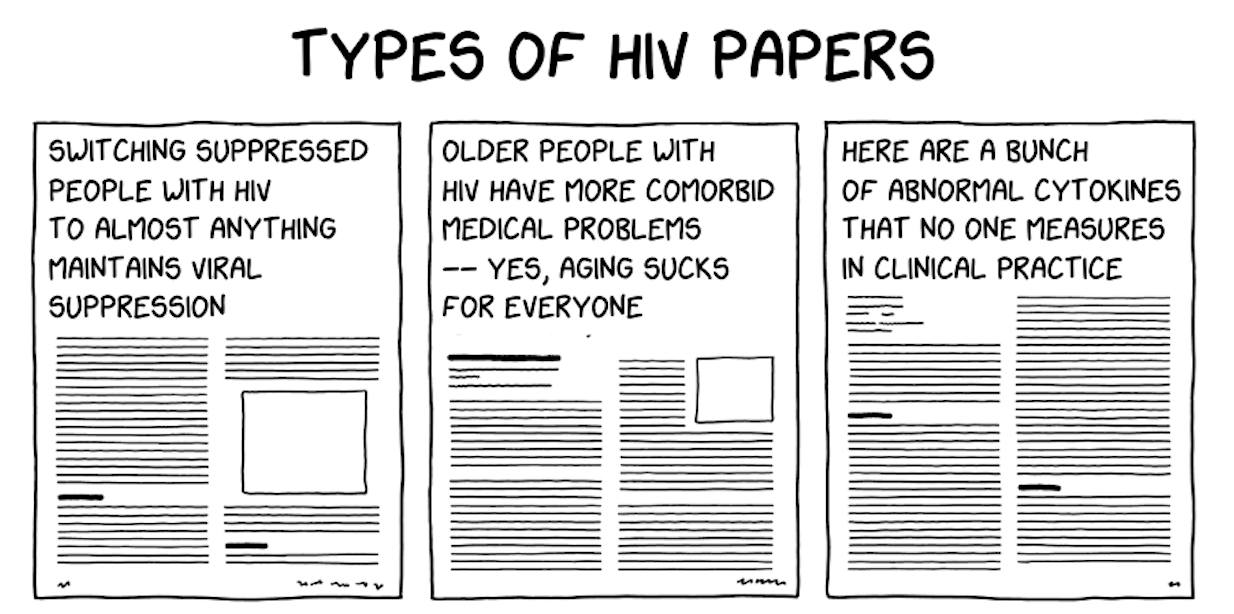

Look, it even got the pole position in my “TYPES OF HIV PAPERS” mash-up.

(Here’s the full version. Dr. Chloe Orkin told me this is my greatest creative accomplishment. Thank you, Chloe, I’ll take it!)

Now, with the CARES, IMPALA, and LATITUDE trials, we know that CAB-RPV works really well even in people with more complex treatment histories. Plus, with the extraordinary effectiveness in those who are viremic and unable to take oral ART — 92% in Atlanta! 98% in San Francisco! — we have a truly transformative approach to ART that can be literally life-saving. A prospective clinical trial of CAB-RPV in people with viremia is enrolling now.

#6: A Novel Malaria Therapy

Amid all the global-health gloom — funding cuts, program shutdowns, rising resistance — came genuinely great news: a novel malaria treatment with a totally new mechanism of action.

Malaria, remember, still kills hundreds of thousands of people annually, most of them young children. In addition, artemisinin resistance creeps worryingly upwards, threatening our best therapies.

Along comes the drug ganaplacide — it works by disrupting the parasite’s internal protein transport systems and, when combined with the existing drug lumefantrine, looks to be strikingly effective. In a large, phase 3, open-label trial across multiple African countries, the combination of ganaplacide plus lumefantrine (GanLum) demonstrated noninferior activity to standard of care, meeting its primary end point. It was numerically even a bit better, with 97% cured versus 94% in the control arm. There were no concerning safety issues.

The manufacturer estimates it will be approved for use within the next 1–2 years. Hooray!

So yes, some years are better than others for our field of ID, but darkness and gloom notwithstanding, there was still an incredible amount of real progress, brilliant science, and solutions to problems that once felt insurmountable. Hey, half the above examples included long-acting formulations of antimicrobials that would have been unimaginable when I started in ID.*

*Dr. Charles (Charlie) Flexner, King of the Long-Acting Institute of Therapeutics, must be beaming.

As always, I’m grateful for the researchers, clinicians, study participants, nurses, pharmacists, study sponsors, and all the behind-the-scenes people who make these advances possible. And for you, loyal readers, who keep showing up even when the headlines tempt us all to look for new jobs.

Here’s hoping your holiday season includes good health, good company, and at least one conversation where someone asks, “So… what is dalbavancin, anyway?” so you can show off — and, if your Thanksgiving table features that one relative who wants to explain why vaccines are “a government plot,” may your cranberry sauce be extra soothing and your patience infinite.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone. Let’s hear what you’re grateful for!

Looking back on these annual Thanksgiving posts, I notice an odd pattern: every few years, the intro turns into a kind of apology. As in, Yes, I know the title sounds upbeat, please don’t attack me. The world feels heavy, the ID bad news scrolls by, and there I am writing about gratitude.

Looking back on these annual Thanksgiving posts, I notice an odd pattern: every few years, the intro turns into a kind of apology. As in, Yes, I know the title sounds upbeat, please don’t attack me. The world feels heavy, the ID bad news scrolls by, and there I am writing about gratitude.

Every so often, you sit down for what’s supposed to be a lighthearted conversation and end up somewhere not just fun, but deeply enjoyable and even profound. That’s what happened when I joined my friends and ID colleagues Drs. Buddy Creech (Vanderbilt, pediatric ID) and Mati Hlatshwayo Davis (Washington University, public health expert) for the

Every so often, you sit down for what’s supposed to be a lighthearted conversation and end up somewhere not just fun, but deeply enjoyable and even profound. That’s what happened when I joined my friends and ID colleagues Drs. Buddy Creech (Vanderbilt, pediatric ID) and Mati Hlatshwayo Davis (Washington University, public health expert) for the

As we await the results of placebo-controlled Covid-19 vaccine studies, what are we clinicians to do when our patients ask us whether they should get a booster this fall? What once was a no-brainer in the early days of limited immunity to the virus — and the

As we await the results of placebo-controlled Covid-19 vaccine studies, what are we clinicians to do when our patients ask us whether they should get a booster this fall? What once was a no-brainer in the early days of limited immunity to the virus — and the

On Friday night,

On Friday night,  The DOTS randomized clinical trial of dalbavancin versus standard-of-care for Staph aureus bacteremia (SAB)

The DOTS randomized clinical trial of dalbavancin versus standard-of-care for Staph aureus bacteremia (SAB)