An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 25th, 2025

Who Gets Sent to ID Clinic? A Field Guide to Outpatient Referrals

Sometimes people ask me what kind of cases get referred to ID doctors in the outpatient setting. Despite what the latest television series might suggest, it’s rarely suspected Ebola (fortunately) or Tsutsugamushi fever — a disease that is much more fun to say by its Japanese name than its common one, scrub typhus.

Sometimes people ask me what kind of cases get referred to ID doctors in the outpatient setting. Despite what the latest television series might suggest, it’s rarely suspected Ebola (fortunately) or Tsutsugamushi fever — a disease that is much more fun to say by its Japanese name than its common one, scrub typhus.

(In Japanese, “tsutsuga” means “hindrance” or “illness,” and “mushi” means “insect” or “vermin”. Now you know!)

Instead, the cases generally fall into one of these four broad categories:

1. Diagnostic dilemmas. The clinical gestalt suggests infection, there’s no diagnosis, and the patient isn’t getting better. You know, Box #4 of the Four States of Clinical Medicine — “No diagnosis, not improving,” the most unstable box to be in. Let’s see if our diagnostic skills can get the patient out of that box as fast as possible.

Fever of unknown origin is the classic example, but it could be a red limb unresponsive to empiric antibiotics, refractory diarrhea, disabling night sweats, or the cough that just won’t go away.

A somewhat different version of these dilemma cases (but still in this category) is the patient reporting extensive infectious exposure, and now new symptoms that could be related. If a construction worker has just returned from an excavation project in Tucson, where he oversaw trenching and grading operations (or whatever excavators do), you’d think of a certain fungal infection if he now showed up with a cough and low grade fever. Or it could just be a viral upper respiratory infection.

Closer to home, infection would be top of the list if a restaurant worker from a New England seafood restaurant had slowly growing nodular red bumps up her arm. Fun fact: the person most likely to have M. marinum isn’t your friend with the aquarium — it’s the sous chef cleaning lobsters with a Band-Aid on a scraped knuckle.

Sometimes it’s just profound fatigue after an infection — in ID, we were seeing post-infectious fatigue long before COVID-19 (after sepsis, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, influenza, lyme), and COVID has certainly increased that pool of unfortunate patients. Yes, many of these referrals turn out not to be active infections, or infection-related, at all — but that’s for us to figure out. We’re the “it might be an infection” people.

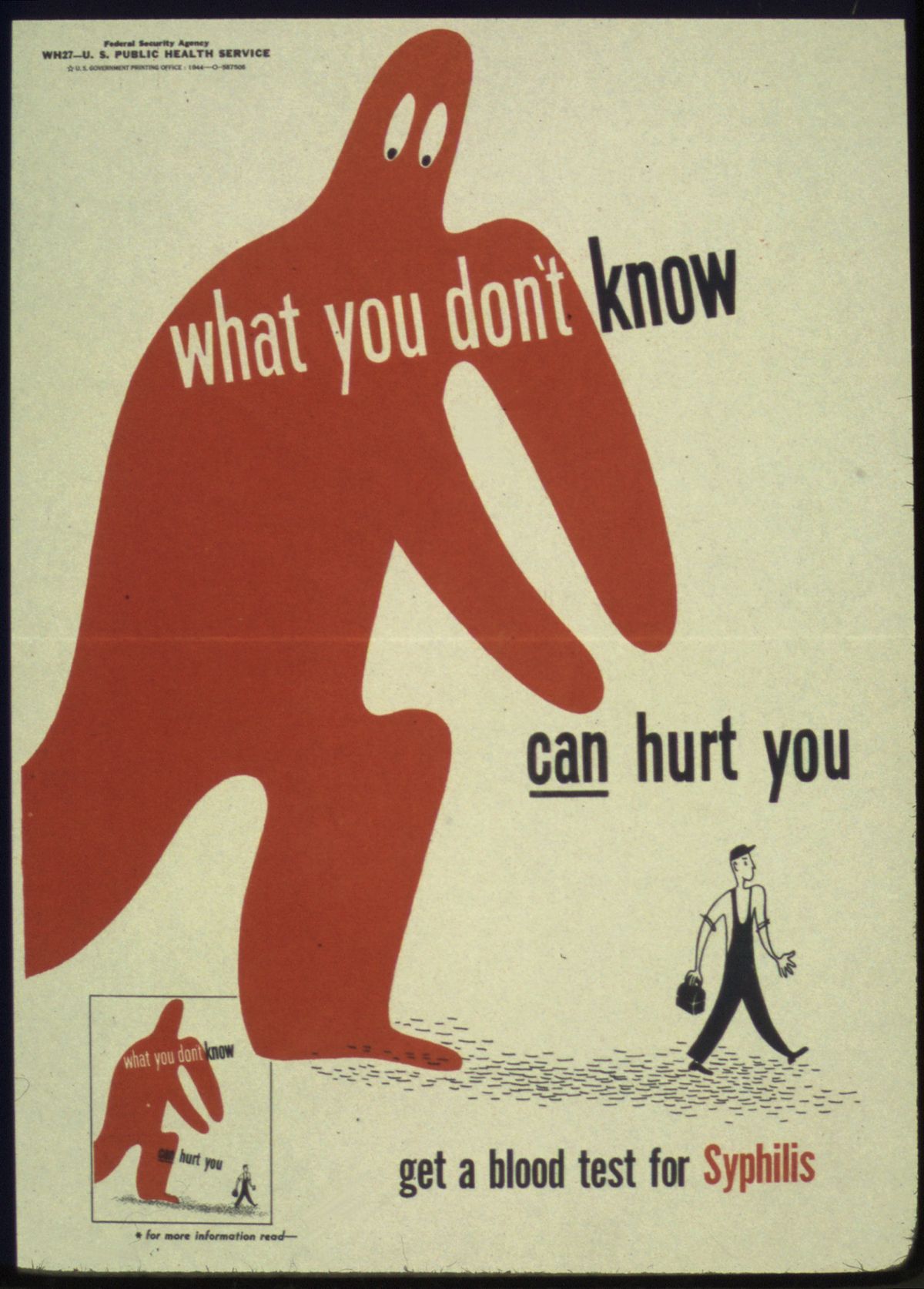

2. Unusual diagnoses to nonspecialists. These are infections that primary care clinicians might see only occasionally, but that land in our inboxes daily. HIV, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacteria, prosthetic joint and other hardware infections, multi-drug resistant bacterial infections, and the full spectrum of syphilis. (Examples of this last one: secondary syphilis with uveitis, or tinnitus, or some other bizarre manifestation of this quintessentially protean disease.) Hepatitis C used to fall into this category, especially in the interferon and early direct-acting antiviral era, but now treatment has become so simple that most patients get treated (and cured!) in primary care. Still amazed at that transformation.

Vertebral osteomyelitis is a striking example of this category — rare to primary care, common to us. A busy first-year ID fellow may see more than a dozen of cases over the year on the inpatient consult service, whereas a primary care clinician will evaluate hundreds of patients with back pain over several years. But chances are good that none of them has vertebral osteomyelitis.

Not surprisingly, many of these patients are diagnosed during a hospital stay. Since most generalists today focus on either inpatient or outpatient care (not both), we often inherit these cases post-discharge after an inpatient consult.

3. Unusual diagnoses — even to us! These are the real fascinomas, the ones that earn a coveted slot in ID case conferences and elicit audible gasps, especially if there are good images.

Here in temperate Boston, parasitic infections and tropical diseases make the list, as do systemic fungi, nocardia (which straddles the line between fungus and bacterium — I hope that’s not insulting to nocardia), and various other medical oddities. Infections that were once common but are now mostly vanquished also show up, and here’s when having gray hair as a “seasoned” clinician (I wonder who that could be) is a plus. One recent example is a referral we received for a fever and an unusual pustular rash that turned out to be … varicella … better known as chickenpox.

But for many of these true rarities (not chickenpox, but rather melioidosis or leishmaniasis or cysticercosis, et al.), there are usually only a handful of true experts, and we ID doctors often act as the conduits to them. Luckily, they’re often generous with their time when we call or email. Thank you, remote consult heroes!

4. Very common diagnoses — but with a twist. Finally, the largest category. These are the bread-and-butter infections that just won’t go away, or keep coming back, or are sometimes particularly severe. Recurrent cellulitis, sometimes complicated by bacteremia and requiring hospitalization. Chronic sinusitis. Nonhealing wound infections. And leading the pack by a wide margin: urinary tract infections (UTIs).

UTIs may never make the headlines in medical mystery columns, but what they lack in novelty they more than make up for in frequency — and in misery, for the frustrated patients who suffer through them. Challenging UTIs are so common in ID clinic that we really ought to start a loyalty program. Fortunately, two of my colleagues — Drs. Sigal Yawetz and Jacob Lazarus — specialize in these cases and generously share their expertise with the rest of us.

If you’re looking for guidance on managing UTIs, you’re in luck: two outstanding new publications have just come out to help clinicians navigate both recurrent and complicated cases:

- A State-of-the-Art review on Recurrent Uncomplicated UTIs in Women, published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

- A comprehensive IDSA Guideline on Complicated UTIs, which includes my colleague Sigal on the panel.

Each comes with practical tools, evidence-based recommendations, and at least one flowchart you’ll find yourself referring to again and again — whether you’re in clinic or on the wards.

Wow, quite the week for deaths of some notable celebrities from my youth and young adulthood — Ozzy Osbourne, Hulk Hogan, Chuck Mangione, Malcolm Jamal Warner (particularly sad, given his age). I can’t say any of them was a particular favorite, though of course I knew of them all, with Chuck Mangione’s “Feels So Good” playing on perpetual repeat during my senior year of high school.

Who to feature here at the end of this ID blog? I’m going to go with Ozzy, in honor of the self-awareness he developed later in life (especially on the reality TV show he did with his very appealing wife Sharon), and as a gift to my mother, who turns 91 today. She loved his music.

That, my dear readers, is sarcasm. Happy birthday, Mom!

That era really was all about the hair, wasn’t it?

And Cleo Laine passed away, too. What an amazing voice! As for guidelines, I am glad IDSA streamlined the definition of “uncomplicated UTI”. It makes sense and will shorten my PowerPoint when I cover the topic with my nursing students. “Infection confined to the bladder in afebrile women or men”. Also glad they included men in that category, finally. Another PowerPoint bullet point gone. 🙂

The rarest I got was for genital ulcers in a woman who turned out to have Behcets Syndrome.

Great round-up and reminiscence of the love-hate relationship I had with ID consult clinic. 1/3 cases ID knowledge easily solved, 1/3 great cases I had to learn more ID to manage, 1/3 wackadoodle fake-Lyme, delusional disorders, etc. Some of my favorite cases turned out not to be ID at all, like the woman with “IVIG-resistant parvovirus B19” (??!) who actually had undiagnosed lupus with hemolysis (and no parvovirus). All it took was listening to the patient and reading the chart – but that’s what ID docs do!

Thanks for that excellent field guide. As a superannuated general internist I got to treat and diagnose syphilitic uveitis in an 85 year old, trichinosis and multiple cases of vertebral osteo including tuberculous, etc., etc. The other musical great who died just a few days too early for your obit list was Tom Lehrer, from your neck of the woods Thanks again.