An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

February 20th, 2024

Variability in Consult Volume Is a Major Contributor to Trainee Stress — What’s the Solution?

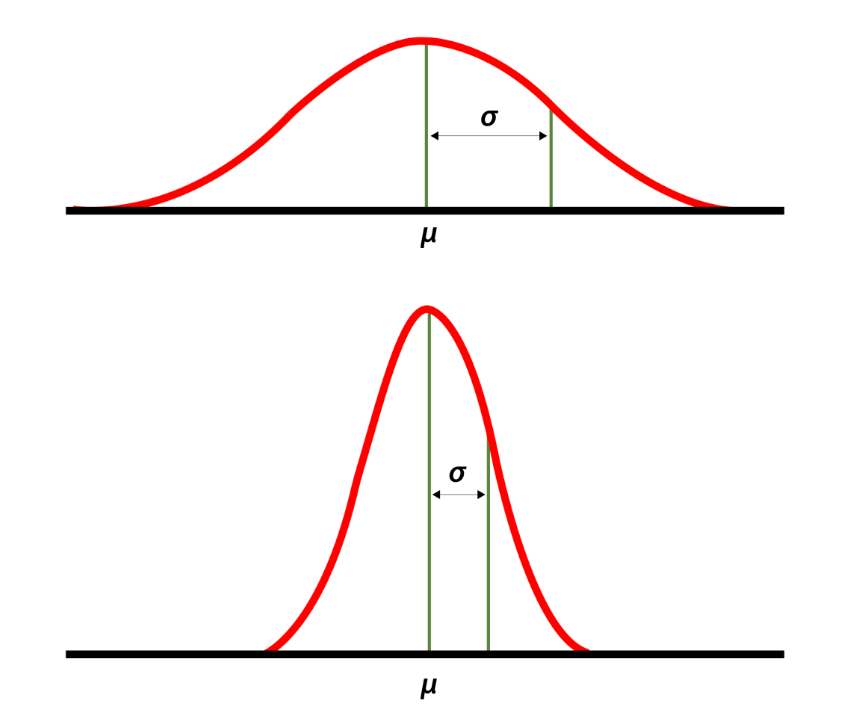

High and low standard deviations around the mean. Source: National Library of Medicine.

Back when he was program director of our ID fellowship, Dr. David Hooper would give the applicants a description of our program. One of the key parts was his estimating the workload — in particular, the number of new consults per day.

“We average three to four consults a day,” he said. “But there’s a high standard deviation around the mean.”

That last part he said humorously, with a smile and a shrug. It was a wonky joke, but everyone got it since it’s well known that consult volume is unpredictable — nothing different about our program compared to any other. But this variance is a critically important part of consultative medicine, one I’d argue is one of the key drivers of physician stress, especially for trainees.

What do I mean? Join me in this thought exercise. You’re an ID fellow with a weekend off, and it’s Sunday night. You’ll be picking up a new service on Monday — first day of a new rotation! — and will be responsible for learning the details of the cases on your team and catching up on weekend events.

Not only that, you’ll also be seeing the new consults that get called in that day. You know Monday will be busy, but how busy?

Let’s take two scenarios for the number of new consults — which would you choose if given the option?

- A day when you will get four new consults — no more, no less. Once you’ve done the fourth, you’re done with new consults for the day.

- A day where your consult volume that day is uncertain. You know that the average number of consults/day in your program is between three and four; however, light days (one or two consults) are balanced out with very busy days of five, six or, rarely, even seven new consults.

I suspect most of us would choose the first option, even though the “average” outcome of choice #2 is fewer consults.

This says a lot about psychology, risk perception, and our decision-making strategies. In studies of decision science, participants often choose the “sure thing” over a potentially more valuable but uncertain outcome — a phenomenon often referred to as “loss aversion.”

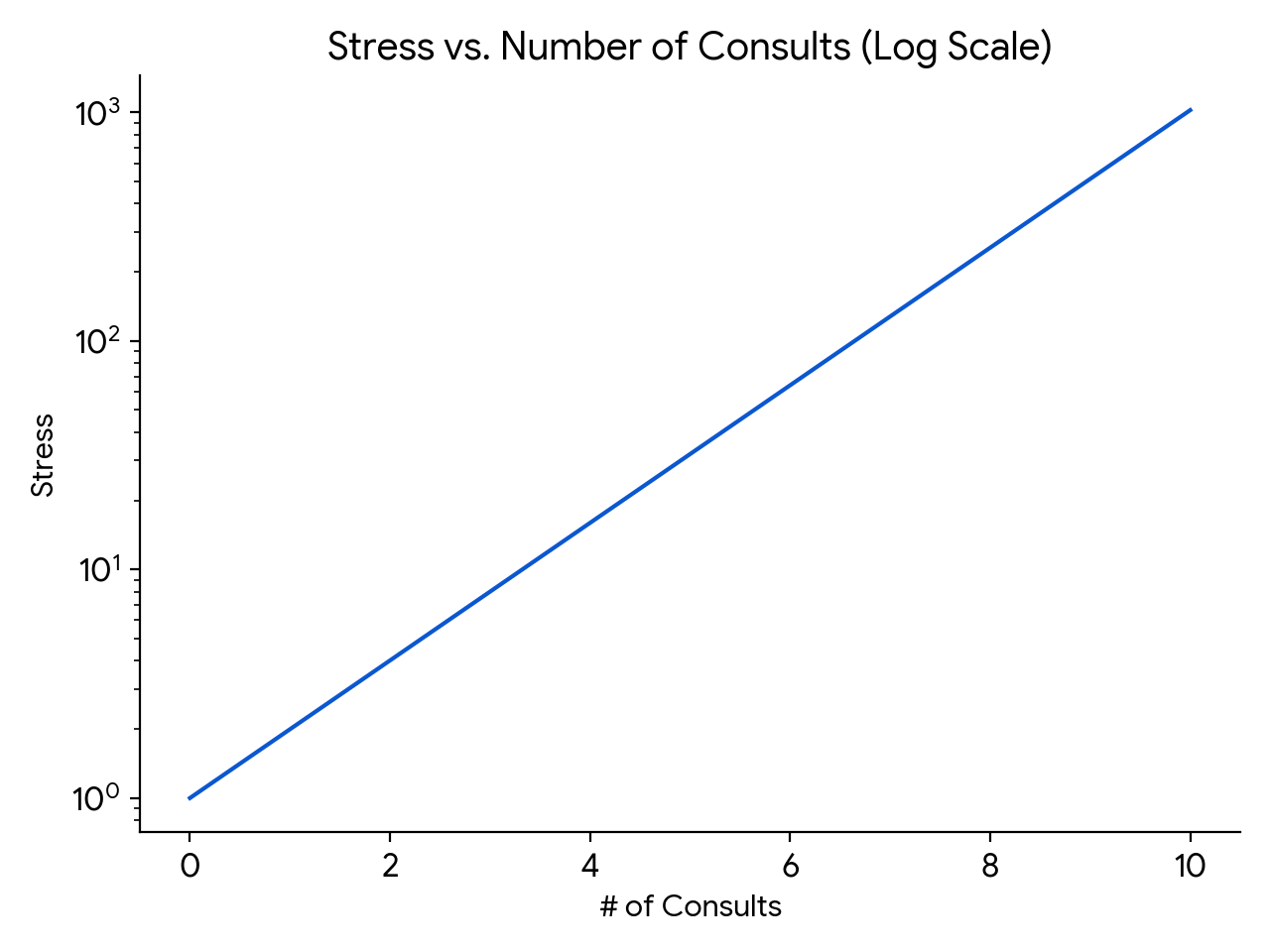

An important point is that the relationship between consult volume and stress does not increase linearly — it’s more like on a log scale, which means that going from five to six consults is much more difficult than going from three to four, even though both just add a single new case. And what this additionally means is that getting six consults is much more than twice as stressful as getting three.

(How about those math skills. Impressive, eh?)

Finally, there is something inherently stressful about living through the amorphous blob of work potentially coming your way in choice #2. The day could start out relatively peacefully, with just a single consult, making you cautiously optimistic but still vulnerable. But then, an hour or so after lunch, the chief resident in orthopedics could page you and say they’ve just accepted in transfer two patients with infected prosthetic joints — both of whom will need your attention when they arrive (whenever that will be).

That hypothetical day still didn’t yield more consults than in choice #1, but the unpredictability of the way they came in made the day seem so much more tense.

(Note: This discussion must seem foreign to ID doctors in private practice, where consult volume directly links to personal revenue. But try to imagine yourself back in the days of your ID fellowship, however, and you’ll get what I mean!)

I thought of this challenge recently since we recently had quite the week when it comes to consult-volume variance. Afterwards, I sent a note commenting about this to Dr. Daniel Solomon, our fellowship’s current Associate Program director. His response:

I think the hardest thing about being on service (and in particular first-year fellowship when they are on the front lines holding the pager) is not the cumulative volume of work. It’s the unpredictability of each day. It is hard to make reliable plans with friends and family when the variance is so high.

I couldn’t agree more.

Solutions? One thing we proposed was to unload some of the simpler cases to an eConsult system, where inpatient medical and surgical teams received clinician-to-clinician advice from us after a discussion, record review, and our writing a brief note in the chart. The issue? As I wrote previously — no one has figured out how to pay for these things. Proposal rejected.

Some say that instituting a “cap” on new consults solves this variance-in-volume problem, and there’s definitely some truth to that. Such caps limit the burden of a high consult day on the ID fellows, much as a cap on admissions does the same for interns and residents. Plus, that uncertainty factor is greatly reduced.

This solution isn’t straightforward to implement, however. First, who sets the right number? ID training programs have a wide range of expected new cases per ID fellow per day. I’m very much aware that our daily average of three to four per day isn’t the same as other programs, some of which have considerably higher volume.

Also, should the cap be the same regardless of the number of patients you’re already following, or the complexity of the service? Should it be the same for general ID consults as it is for transplant and oncology services, which have an average complexity per case that’s much higher? And how do we account for variable team structures? Some regularly have rotating medical residents and/or students on board to help defray some of the work, while others rarely have these learners.

One other issue with a cap relates to the inherent value of clinical volume for volume’s sake. There’s a cliché in clinical medicine that goes, “The more you see, the more you see.” Since many ID programs (ours, for example) have only 1 year of intense inpatient clinical training, why not make the most of it, provided the volume isn’t too brutal? We all know that there’s no better way to learn about a clinical entity than to care for a patient who has it — the first-year ID fellow who sees CNS nocardiosis, or falciparum malaria during pregnancy, or disseminated histoplasmosis will never to forget those distinctive but relatively rare diseases, to choose just three that recently popped up on our inpatient service.

Although it doesn’t seem so at the time — an understatement — even doing a consult on “routine” cases brings value. Seeing many examples of Staph aureus bacteremia, or infected abdominal collections, or osteomyelitis under sacral pressure ulcers cumulatively helps develop an approach to these common entities, and to appreciate the wide variability in clinical presentation and management.

So far this discussion about the cap looks at it from the fellow perspective. It doesn’t address the fundamental cause, which is that the consulting services need our help caring for their patients, and it’s our mission to help them. That the volume of these requests is unpredictable isn’t their fault. Hence, once a trainee is capped, this work then must get done by someone else, right? Is it the on-service attending, who is still responsible for staffing the fellow-seen cases on this already busy day? Some other faculty member waiting in the wings, eager to do a late afternoon bunch of consults? Who has those faculty?

In summary, there are pros and cons to putting a cap on new consults for ID fellows. I’d be interested to hear — do you have a cap on new consults in your fellowship program? If so, what is it, and how did you decide on a number? Who’s responsible for doing the work over the cap? Share your thoughts in the comments section.

And enjoy this quite remarkable video, which somehow escaped my notice when it first appeared. Glad they remembered to press the record button!

I truly understand the total unpredictability of consults having been in private practice since 1981. I also know that the work load of residents and fellows are always evaluated and the goal is to not I restless them. I am not one the the “old farts” that disagrees with making work hours more reasonable but do worry (and have seen personally) the struggle that some new trainees have when choosing private practice. As you said, it is our duty to help our consulting physicians and being an ID consultant for all these years I have never been able to tell the referring physician that I have “capped.” I feel that ID training programs need to somehow balance the work load of the fellows with the realistic preparation for private practice for those fellows that are targeting a career in clinical ID

Fantastic and difficult topic to address. Kudos on finding that OK GO video BTW–it’s a staple in our house.

I would love for someone to do a survey on this topic across all training programs (and I know that some versions of this have been done…including perhaps one I initiated by email a few years back). While it would be helpful to understand averages across what other programs do, I realize there is so much variability between programs that it really becomes an apples-to-oranges comparison. Still, I think this data would at least be a starting point, and if IDSA or ACGME or some eager fellow looking for an ID med ed project were interested in collecting the data, that would be incredible!

We have “soft” caps (which are problematic in their own way) of no more than 5 new consults or 16 patients in total per day for fellows. After that, Attendings are supposed to help out with follow-up patients, new consults, and note-writing. The challenges are 1) not all consults are the same (s/p BMT on hospital day#30 vs Staph aureus PJI s/p HW removal) so the caps are hard to apply equally (as you point out), 2) they are difficult to “enforce” from both the Attending and the fellow side, and 3) it doesn’t make sense to apply them equally across all fellows since fellows can be a very different degrees of clinical competency.

Regarding the comments re: preparing fellows for “the real world,” I would argue that more is not always better. If a fellow is so exhausted and burned out from workload, the quality of the learning goes down. Yes, we need to prepare fellows for high-volume, high-acuity settings but this should be done in a graduated fashion as fellows demonstrate competencies that enable them to see more patients. They are still learning. And they need time to think, read, talk with patients, talk with teams, talk with pharmacists, talk to the lab, prepare case conferences, etc AND have a life. Fellowship is not Residency 2.0 IMHO.

Try this thought experiment: A new consult on a moderately complex patient takes ~1 hour (chart review, interviewing and examining the patient, talking with radiology/micro/other consultants/etc, presenting the patient to the Attending, communicating recs, writing the note, etc). A follow-up patient takes ~40 minutes (pre-rounding, interview/exam, discussing the patient on rounds, communicating recs, writing the note). **These time estimates on on the shorter side**. If a fellow gets 5 new consults and has 11 follow-up patients, you are talking about a 12+ hour day for the fellow. This doesn’t include time for approving antimicrobials, attending didactics, eating lunch, etc. We should also remember that the amount of patient data in the EHR is more voluminous and more complex than it ever has been. Caring on with this schedule day-in and day-out during an “intensive” year of clinical rotations gets extremely exhausting after a while. The cognitive load that fellows are managing is SIGNIFICANTLY higher than that of an Attending. Once you’ve been in practice for several years, 5 new consults and 11 follow-ups seem fairly manageable. But we need to remember that fellows are still learning. Fantastic article on cognitive load during inpatient consults here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34039851/

We also have to remember that we are dealing with significant barriers/challenges/opportunities as relates to the ID workforce and recruiting the next generation of ID physicians. While I in no way support “making a fellowship easier to appease or attract trainees” I do think we need to be intentional about how we structure learning opportunities, rotations, and patient volume for our fellows and how we demonstrate to them that their learning and education are a top priority. There will always be a balance between learning and service but we do need to ensure that fellows do not feel as though they are workhorses to generate profits for the hospitals by seeing more and more patients.

I don’t have many answers but I am grateful for this conversation and I hope to continue to learn from and reflect with this wonderful community on these important issues. Thanks for this piece!

Thank you for this incredibly thoughtful comment! Clinical medicine is hard, and for trainees, especially so. Variability is a really tough challenge, and I hoped in writing about it we’d take the first step in solving it.

-Paul

Hi. We do not have a cap, except for the time limit, we only accept new consult request if they arrive until 9 am that day. We use printed request forms for consults in my institution. Seems that we have similar average, also similar variations in number of consults. Our main problem is that the person who is doing consults also has to attend for hospitalised patients at our ID ward, due to short staffing. I am very interested in our productivity, how much time do you aproximately have for simple and complex consults. Thans for this post

I’m sure stress is bad for everyone. I was an FP in a small town practice for 42 years.

Still, hard to find a lot of sympathy for other privileged people (like myself) earning a generous income and having meaningful work.

Consider doing ID consults in Ukraine?

We do have caps on our fellows (4 new and 12 old patients, down from 5 and 15). We also see that not every fellow, particularly at the beginning of fellowship, can manage that workload. That has led to some introspection about why this was needed, and why the “old ways” are no longer sustainable.

Patients are more complicated than they used to be. Many of the therapies available today were not available 15 years ago, or even 5 years ago. For a gut check, think about how many times you have wondered “What’s this new monoclonal/small molecule and what does it do?”

Data comes back much faster than it used to. We now have technology which gives species level identification and a basic understanding of resistance patterns within an hour of the blood culture turning positive. We no longer have to wait 3-4 days for ID and susceptibility testing, 7 days for viral culture, etc., during which time we can spare some of our cognitive load while we tend to other patients.

There is laserlike focus on decreasing lengths of stay requires timely and consistent responsiveness from the ID team.

The more consults, the more interruptions to the day. Psychological research suggests that constant interruptions (such as a pager….ahem) cause a drop in IQ by about 10 points. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2005/apr/22/money.workandcareers (We could argue the validity of the study, but it does resonate with personal experience). We put our fellows in this type of environment and expect them to thrive?

Another fundamental question is whether fellows are learners or essential workers, just there to take care of patients. The truth is that there is substantial overlap between the roles, but nobody benefits when the fellows are not in an environment conducive to learning. The other truth is that yes, part of their training is to learn how to manage a high census with rapidly changing needs. These roles do require balancing, and of course balancing comes with trade offs.

The conclusion I have come to in recent years, particularly in light of recent Match statistics, is that fellows cannot be the only part of the workforce seeing patients. We have a responsibility to ensure a balance education, and when an institution finds itself short on fellows, increasing their time on service to fill holes at the expense of other educational experiences is neither a sustainable nor acceptable solution. So why wouldn’t we apply the same philosophy to daily censuses?

I don’t think anyone can say that a ID fellow has a generous income especially with the hours they work. Managing stress and workload is a huge part of attracting and retaining ID fellows.

Have a “flex” nonteaching service to eat up extra consults if there are more than four per teams, and or dealing with late consults. Though I’m not really sure how to pay this flex attending, do they count as having one block of work if they’re on, or not really. Or you can schedule this flex attending to have half day output in AM, and In-patient “flex” in PM for overflow, to make it a block of work. Or you can count this into their total wRVU. i guess I’ve done too much non teaching service by now and are totally biased.

I do not even know how to express my shock, my surprise , my disappointment , my lack of understanding . I can only say that physicians do not want to be physicians any more . They do want to continue to have the income that physicians have always had, and do not tell me that physicians work long hours , more than other professions for that is not true . Physicians have forgotten that it is a blessing and a privilege to be a physician and to be able to alleviate suffering and in some cases to heal the sick . Now days , Infectious disease physicians do not want to take care of “ stable “ HIV infected persons , Endocrinologists don’t want to care for “ stable “ diabetic patients , Cardiologists don’t want to take care of patients with “ stable “ angina ,congestive heart failure and “stable” valvular heart disease , Nephrologists don’t want to take care of patients with “ stable “ renal failure, etc, etc, etc, and physicians want to only see two or three consultations a day . All of these is truly beyond me , i just can not comprehend any of it , i am sorry , but we have become now not just part of the problem with American Medicine , once upon a time the very best in the world , but we physicians , especially infectious disease physicians, have become THE PROBLEM . It is sad, it is disheartening is beyond my comprehension.

Having the privilege of interviewing candidates for residency and fellowship, I disagree with the assertion that physicians don’t want to be physicians anymore. These young future doctors are all in and will change the world in ways we never though possible.

Physicians don’t want to be physicians *at the expense of their own well-being or that of their family and other loved ones*.

This is something the medical profession has ignored for far too long, and we need to catch up. We and our fellows are most useful to our patients when we are performing at our best.

Dear Paul,

I agree with the observations about consult volume in the comments (particularly the thoughtful comment by Darcy Wooten!). Particularly in academic medical centers, we have patients of ever-increasing complexity, a large volume of data within the EMR, accelerated test and patient turnover, and more and more scenarios that require multi-disciplinary decision-making involving multiple specialties – radiology, microbiology, different surgeons, etc. And as pointed above, the teams are not uniformly assigned an equal distribution of “straightforward one-and-done’s” versus “let’s discuss with the larger group in the department conference” consults.

Reflecting on my experiences as a fellow over the past two years, it’s clear that the overall number of total consults across the hospitals has increased. To use consult note lingo, my diagnosis is that the etiology of this surge is multi-factorial – perhaps the corporatization of Medicine with mounting pressure for higher bed turnover, with clinicians increasingly opting for consultations due to time and resource constraints in managing conditions that previously might have been handled independently. If you are a primary team managing an ever-increasing high-turnover patient list and you face penalties associated with length of stay, you may be better off ordering all the consults you might need at the outset. Also, a substantial portion of patient care, both within academic and non-academic medical systems, is delivered by APPs, whose collaborative dynamics with physicians may vary across different settings, potentially leading to increased consultation rates for non-routine presentations or complex cases. I also acknowledge that these examples might not apply to private practice – I’m speaking from a fellow’s perspective.

We also all have to deal with the escalating administrative requirements of modern medicine, made infinitely worse by the way we use our devices and technology. We have created this pervasive expectation of constant availability perpetuated by an email and InBasket culture that is conducive to extreme multi-tasking and keeps fragmenting our attention. Seeing consults all the while having the mental residue of unfinished work lingering somewhere at the back of your mind – the prior auths that need to be appealed, the additional mycobacterial susceptibility form that needs to be faxed, the “urgent” e-mail requiring a signature, etc, can be challenging for a first-year fellow until you figure out your own system. This is just the reality of practicing academic medicine in 2024 and we must adapt and learn how to handle these demands. But the incessant task-switching with the nagging brain residue of unfinished work can be a major cognitive strain for new trainees and can lead to burnout.

There were those days in my first year of fellowship when despite having fewer consults, the hours slipped away in a blur and I would ask myself, “Wait, what did I do all day??”. A typical day would be – you start working on a new consult, only to discover it’s been misrouted to the wrong team – maybe a transplant case landed with the general team. You don’t want any delays in care and quickly start drafting an email to rectify the consult assignment and initiate its re-triage. But before you hit “send”, an unnecessarily loud BEEP BEEP raises your heart rate – your page demands your immediate attention. “Please call to discuss patient XYZ – STAT.” You are a responsible fellow, so you promptly respond (because it said “STAT” after all), only to learn that a patient you saw maybe two weeks ago is IMMEDIATELY being discharged, and “oral options” have become as emergent as a Code Blue. You are a friendly nice person, so you delve deep into the chart, refreshing your mind on the history and cultures of two weeks ago. It requires some back-and-forth clarifications about nebulous “allergies” with the team, but you finish the task in less than five minutes. Just as you’re hanging up the phone, the now more-visible-than-ever InBasket icon (after Epic’s recent update) steals your focus – an urgent issue with an outpatient clamors your attention! Returning to your initial task of drafting a re-triage e-mail, you’re once again interrupted by yet another page, and this relentless cycle of interruptions while your attending waits to round leaves you feeling like a juggler desperately trying to keep multiple balls in the air.

Recently, I read the book “Attention Span,” by Gloria Mark, who is a cognitive psychologist that studies attention. I highly recommend this book and her insights are very practical. I even changed the way I worked (you may have noticed a much-improved workflow in our clinic! Hooray!). She introduces a helpful vocabulary on how to talk about attention. These “nested interruptions” (a concept from the book) and socio-technical dynamics of the EMR, e-mail culture, etc, are now very entrenched in our medical practice and consultation workflows in 2024.

I also acknowledge that faculty have their own distinct set of administrative obligations, teaching, lab work, meetings, and grant deadlines. However, within clinical service, attendings have much greater autonomy/power to streamline case management efficiently (or not), teaching trainees (or not) and establishing their own preferences and expectations.

Consultative work continues to be rewarding and fun (especially with learners) and I hope we can figure out a way to improve fellow learning/happiness and the reality of our clinical operations/needs.

Great points on the complexity of managing consult volume. This has been a discussion that is at the forefront of every PD/APD’s mind. We know that each year our volume and consults demands are increasing while at the same time getting more complex. Rarely in our academic setting are we asked to comment on a CAP or cellulitis, instead our consults are Day #38 in the hospital after 17 different surgical operations after multiple GSW’s now with fever and leukocytosis. We also have a duty to prepare our fellows for the reality of the job market – whether that be private practice (high consult volume) or academia (need to balance clinical with all the other required asks that come with the job). It can feel impossible!

Several of us have worked on a white paper that takes a look at how some programs have managed to find this very delicate balance. We have submitted it and hope to hear back soon! As Dr. Wooten notes – every program is different & we need at least a starting point to go off, which is what we hope this paper will do!

I am always so pleased to be a part of our fellowship program and love that the ID community is genuinely concerned about how to ensure ID fellows are not only fantastically trained but also ensure we’ve created an environment that makes it easy to love the wonderful world of ID.

Missing from this conversation is how APP (advanced practice providers- NPs, PAs) can and ARE being leveraged in this new age of team-based care that is certainly the future of healthcare. We have to rethink how we provide care for a variety of ID patients on teaching services to ensure we are providing the best quality care, but also providing an outstanding learning experience for clinical learners. Opening up the conversation to how can our ID services best utilize APPs (yes- even at busy academic centers like my own!) to support first patient care, but then closely behind that training the best ID providers is seriously needed. We need to work together on this care-team models to make this happen and not continue to believe that an ID fellowships or medicine ID rotation is separate from the APP workforce and utilization.

This may not be totally relevant for the ID community, but just as travel expands one’s horizons regarding world cultures, perhaps exploring the consult culture in other services would be of benefit from an exploratory perspective.

In Cardiology at my academic medical center, we provide in-house consultative service 24/7/365 and the overnight and weekend fellows will drop whatever they are doing to respond to STEMI codes. We are not allowed to put off non-urgent consults for the day team to see (or for ourselves the next day). In general, our consult volume without residents on-service runs between 8-12 new consults per day, the majority of which start at 1-2pm after the primary teams round and have lunch.

On the individual level, it becomes immediately apparent to every fellow that consults must be seen and completed as soon as possible because the future is always uncertain. Lassitude is always punished.

On the team level, we have seen that the most effective way to mitigate the stress and burden of responsibility is to have a second fellow on a light rotation (in our case, CCU, because the unit is run by residents) whose secondary responsibility is to help the consult service. This person will watch the consult list on Epic and be able to see how many have piled up for her co-fellow, and jump in as needed. Of course, with a workforce of five fellows in the hospital at any one time, we have the flexibility to do this and not all services would. But it is reassuring and cuts burnout to share work with a peer and have someone you can tap for help. It is still hard and stressful, but better when shared.

As a fellow, the hardest part of consults was that they were routinely ignored. You spent an hour handwriting a detailed plan of antibiotics and recommendations. On the private side, you could not put in orders. On the public side, the orders were discontinued. With only one fellow at each hospital with roughly 300 beds each, the service was limited to forty patients on service. More than this and we would need to “sign off” cases to see new consults. I think that attendings should cover the service when the numbers add up. Or screen the consults so only the most urgent are seen. Especially since the pay for ID is much less than hospitalists or even clinic IM. It’s a labor of love at this point. I did 18 months of hospital consult service, this should be the standard to see a breadth of knowledge.

Well not trying to be too harsh but if you’re intimidated by 4 upcoming consults perhaps ID isn’t/wasn’t the best choice for you. I completed my fellowship 20 years ago so I’ve been out a while. I choose my fellowship hospital based on its high volume. That choice meant learning to handle a service that regularly carried 15-25 patients (split between 2 fellows) plus multiple consults everyday. So when I went into private practice I had no reservations about handling high volumes. A busy 500 bed hospital with a 3 man group we regularly carried 40+ active consults and the on-call doc could take 5-15 new consults each day. So I personally think capping a teaching service is rubbish. Honestly you’ll be ineffective to a private ID group if you can’t manage higher numbers.