An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 29th, 2012

A Quick Note to Time Magazine

Thanks for the recent coverage of HIV treatment.

One small suggestion: in the future, try to find some some stock photos of HIV medications that are somewhat more up-to-date than, um, 1997, which is what you chose here and here.

In our field, seeing these original AZT, ddC, and nelfinavir tablets is kind of like seeing cathode ray tube computer monitors, or cars with fins.

Sincerely,

Paul

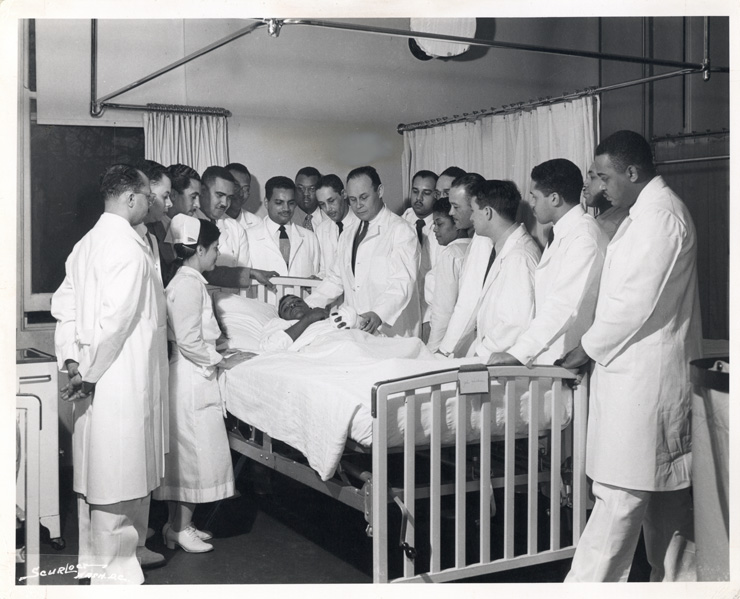

p.s. This cover is one of my all time favorites.

July 26th, 2012

Pigs are Flying: Written Consent No Longer Needed for an HIV Test in Massachusetts

Let the record show that as of July 26, 2012, a person in Massachusetts can legally get an HIV test without signing a written consent.

Let the record show that as of July 26, 2012, a person in Massachusetts can legally get an HIV test without signing a written consent.

Hooray.

There, that wasn’t so hard, was it?

July 25th, 2012

AIDS Quilt, the Early 1990s, and Sadness

The early 1990s has potentially many associations — the break-up of the Soviet Union, the first Gulf War, the World Trade Center and Oklahoma City bombings, The Lion King, Forest Gump, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, and the cancellation of the baseball season, to name a few.

The early 1990s has potentially many associations — the break-up of the Soviet Union, the first Gulf War, the World Trade Center and Oklahoma City bombings, The Lion King, Forest Gump, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, and the cancellation of the baseball season, to name a few.

But we HIV/ID specialists will always remember that period for something else — namely, that deaths from AIDS in the United States peaked then, making it an especially challenging time to practice.

I was reminded of this during the International AIDS Conference this week in Washington, as panels of the AIDS Quilt are on display both in the conference center and elsewhere around the city.

It seems like in every large display — which usually has 10 or so individual memorial quilts, each 3 X 6 feet — most of the deaths being acknowledged occurred in that 1990-1995 period. And the 1994 and 1995 deaths strike me as perhaps the most poignant, because these young men and women just missed getting lifesaving treatment.

And though I didn’t know them personally, I did know Larry, and Greg, and Bryana, and Tony, and Bob, and George, and Tonya, and wish they could have lived just a bit longer. Then they’d have the chance to be saved by ritonavir, indinavir, nevirapine, etc., which were just a few short months away from being approved.

There’s just something so sad about that.

July 23rd, 2012

IAS-USA HIV Guidelines Updated

With the International AIDS Conference in Washington just starting, the International Antiviral (ahem) Society-USA has revised its HIV treatment guidelines, updating the 2010 version.

As has been the case for several years now, it’s published in JAMA and also available on the IAS-USA web site. It’s a well written, evidence-driven summary of the current state of HIV treatment, with a highly respected authorship group, headed again this time by Melanie Thompson.

It is more fully covered by Abbie Zuger on Journal Watch: AIDS Clinical Care, but some medical highlights:

- HIV treatment recommended for all, with the possible exception of HIV controllers and long-term nonprogressors.

- They have shifted towards listing full regimens rather than “NRTI pair + key third drug”.

- Some abacavir/3TC-based regimens have moved into the “Recommended” category, provided the HLA-B*5701 is negative and the HIV RNA is < 100,000 cop/mL.

- Tenofovir/FTC/elvitegravir/cobicistat (“Quad”) is listed as an alternative treatment, with an acknowledgment that this treatment is not yet approved.

- There’s a section on PrEP with tenofovir/FTC.

- Viral load and CD4 monitoring can be reduced to twice-yearly in clinically stable patients. (Of course you don’t need to measure CD4 at all once someone is stable on treatment — see here for an explanation.)

- There’s a box nicely summarizing all the changes since the 2010 version.

- The “USA” part of IAS-USA is to distinguish this from the other IAS, which is still called the International AIDS Society.

- Abbreviation for “integrase inhibitors”? InSTIs, which is hard to type, but not nearly as hard as iPrEx.

- If you want to target the areas of controversy in the field that nonetheless deserve some sort of comment — timing of HIV therapy with HCV, abacavir and CVD, use of therapeutic drug monitoring, etc — simply do a search on the word “might.” Guidelines writers love that word when the data are inconclusive.

July 16th, 2012

Sizzling Summer Serratias

Several ID/HIV items to contemplate as the heat really kicks in here in the torrid USA:

Several ID/HIV items to contemplate as the heat really kicks in here in the torrid USA:

- TDF/FTC approved for pre-exposure prophylaxis. The challenging issues of defining the best candidates for this strategy — and finding the providers to prescribe it — still remain, but FDA approval should at least help justify insurance coverage if clinicians choose to offer it to their patients. Some other controversies? Sure!

- Dolutegravir + abacavir/lamivudine bests TDF/FTC/EFV. All the info we have thus far is in the press release, but let the record show that this will be the first time a regimen is significantly better than TDF/FTC/EFV in its primary analysis. The results are driven by more discontinuations for adverse events in the EFV arm. Further details eagerly awaited.

- Severe Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease outbreak in Asia. It’s apparently caused by enterovirus-71, and to me it’s still perplexing — despite what this brief article in our local paper says.

- Toxoplasmosis linked to suicide risk. I’m a big believer that many chronic infections are in fact benign — we live with microbes, remember? — but data linking CMV and now toxoplasmosis with adverse outcomes are now out there (here, toxo associated with “self-directed violence” — haven’t heard that one before). And all ID docs know that it’s more appropriate to blame your diet than your cat, right? Last, I’ll say it again — is there a better name for a scary Infectious Disease than Toxoplasmosis gondii? Yikes, just saying it makes me frightened.

- Bad tick-related illness season. That was a completely anecdotal impression, my apologies for no reference.

Meanwhile, today’s title is brought to you by the distinctive red color when Serratia grows in culture.

And can anyone provide the “real” pronunciation? (Bonus points.)

July 10th, 2012

Are ID Doctors the Worst Dressed Specialists?

Unusual exchange the other day with one of my (non-ID) colleagues. All dialogue reported verbatim:

Unusual exchange the other day with one of my (non-ID) colleagues. All dialogue reported verbatim:

Non-ID guy: Hi Paul.

Me: Hi Jon.

[I’m expecting the next line to be: “Quick question: I’ve got a patient with a positive PPD and a history of BCG, etc.” Instead, it’s this bizarre comment:]

Non-ID guy: You know, I would say that ID doctors are the most poorly dressed doctors in the Department of Medicine.

Me: Huh?

[You can understand my response — where did this come from?]

Non-ID guy: No offense [right] — it’s just when I look at the ID group, you are not the most well-coiffed clinicians. I can tell you guys from across the room.

Me: …

[Prolonged silence — frankly, I’m not sure what to say. Of course I’m instantly self-conscious about my own wardrobe, which is pretty standard Boston — clean but slightly shabby doctor attire. Hey, this isn’t NYC — no suits here.]

Non-ID guy [sensing my discomfort — I hope]: Not referring to you, of course.

Me: Of course …

Non-ID guy: Anyway, quick question — can I give the zoster vaccine to someone on inhaled steroids?

Me: Maybe if you paid me for every one of these questions I’d have more money to spend on nicer clothes.

[I didn’t really say that.]

I’ve been trying to get my head around what this doctor was referring to, looking with a critical eye at our faculty.

Sure, we’re not as sharp looking as the Cardiologists — or even close to the Dermatologists, most of whom look amazing — but I don’t think we’re that far off the norm.

Your thoughts?

July 5th, 2012

Home HIV Test Big News — But Why? And What Impact Will It Have?

The recent FDA approval of a home HIV antibody test (OraQuick In-Home HIV Test) was covered just about everywhere. It’s an oral swab test, takes 20-40 minutes, and will be available over-the-counter.

The recent FDA approval of a home HIV antibody test (OraQuick In-Home HIV Test) was covered just about everywhere. It’s an oral swab test, takes 20-40 minutes, and will be available over-the-counter.

How big a news story was it?

- Several hundred sources featured it on the day of the announcement, and the total count is now well over a thousand

- It grabbed the coveted far-right column of the front page of the New York Times — not much HIV or ID-related information makes that spot these days

- It’s been picked up by numerous international media outlets; Canadian HIV specialists are calling for approval of the test in their country as well

- Naturally, our First Watch service made the story #1 today

Note that the coverage of the approval has been overwhelmingly favorable.

I’m glad that the approval has raised the importance of HIV testing in the public’s eye, but confess I was a bit surprised by just what a huge news story this has become. Furthermore, relatively few have questioned how useful this test will be. After all, another home HIV test was approved for use in 1996, and its impact has been limited.

(Some believe that this is because it’s relatively costly and is not really a true home test — it requires a fingerstick at home, then mailing the specimen into a central lab.)

It’s significant that something similar to this recently approved true home test was initially under review way back in 2005. Shortly thereafter, my inimitable colleagues Rochelle Walensky and David Paltiel published an opinion piece in the Annals of Internal Medicine entitled, “Rapid HIV Testing at Home: Does It Solve a Problem or Create One?”

The provocative title says it all: They argued that home testing, while helping to increase the number of tests and decrease stigma, would have a negligible effect on identifying more people with undiagnosed HIV infection — all while creating additional problems due to the inaccuracy of the test:

Home HIV testing will attract a predominantly affluent clientele, composed disproportionately of HIV-uninfected, “worried well” persons and very recently infected persons with undetectable disease [due to the window period before seroconversion]. This will have the perverse effect of increasing the proportion of false-positive and false-negative results, while making little appreciable dent in the size of the undetected HIV pool.

So hooray for the normalizing of the HIV test.

But whether the home test will actually do much to identify those at greatest risk remains to be seen.

June 29th, 2012

HIV Testing Roundup, and a Brief Rant

I’ve written so many times about HIV testing that a complete list of the headlines fills two full web pages.

But since the last entry on the topic was more than a month ago, one might think I’ve lost interest in the topic.

Never!

Three items on the HIV Testing radar, two national, one local.

First, for a classic good news/bad news report, read these latest data from CDC on previous HIV testing among newly diagnosed people with HIV in the United States. Among the highlights/lowlights:

- Good news: 60% of more than 50,000 newly diagnosed individuals reported having a previous negative test, many within the previous couple of years so that their HIV was diagnosed early.

- Prior negative testing was correlated with factors associated with access to care and high awareness of HIV risk: whites, individuals aged 13 to 29, and males reporting male-to-male sexual contact as their sole risk factor.

- Bad news: blacks, those aged ≥50, heterosexual contact as the sole risk factor, and males reporting injection-drug use were least likely to have a prior negative HIV test — and also far more likely to progress to AIDS at or shortly after diagnosis.

Second, could rapid HIV testing in pharmacies be part of the solution?

This sounds like a great initiative, as there is little doubt it’s easier for many people to go to their pharmacies than their health care providers. I’ll be particularly interested to see how this is implemented on a practical level, including feasibility, cost, acceptance rate, and most importantly, how people with positive tests get linked to care.

Third, we’re only about a month away from when it becomes legal in Massachusetts to obtain an HIV test without written informed consent — law signed in April, “official” July 31. (We’ll be the last state to drop the requirement, for the record.) It’s not an “opt out” policy — verbal consent is still required — but it’s substantial progress nonetheless.

All good, right? Not so fast.

The privacy part of the HIV testing law — which states that HIV testing results cannot be disclosed without a patient’s written consent — has not changed. Some (I hope a minority) have interpreted this to mean that written consent is still required before the test result can be reported by the lab — even if that means simply putting the result into the patient’s medical record (a record already protected by HIPAA). To quote/paraphrase an email forwarded to me from another institution:

… although the law now permits oral consent, we must still obtain written consent to share the test or results with any provider – meaning we still need written consent to include this information in the medical record.

It goes without saying — but I’ll say it anyway — that this bass ackwords interpretation obviously leaves us back where we were before the law changed. Thank goodness it’s not an interpretation shared by all institutions and practices.

And, for the record, it’s an intepretation that is utterly at odds with the intent of the change in the law, which was to expand HIV testing by removing written consent — so that people with this potentially fatal infection can access lifesaving treatment and stop spreading the virus to others.

So glad I didn’t go to law school. I’d spend hours a day with smoke coming out of my ears.

June 24th, 2012

ID Learning Unit — Choosing a Quinolone

We love quinolones on medical services, and it’s easy to understand why. Advantages:

We love quinolones on medical services, and it’s easy to understand why. Advantages:

- Ideal spectrum for several common infections, including community-acquired pneumonia, UTIs, and more complex infections when combined with other drugs

- Great oral absorption

- Few drug-drug interactions

- Once- or twice-daily dosing

- Generally well tolerated

- Reasonable cost

But how do you choose between them? Below, in a concise and admittedly somewhat oversimplified table, is all the medical intern/resident/hospitalist needs to know about our friends the quinolones:

| Drug | Activity vs gram – rods (rank) | Activity vs gram + cocci (rank) | Activity vs Anaerobes (rank) | Metabolism | Comments/Fun facts |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 3 | 3 | Kidney | Don’t use for Strep pneumo; no association with increased cardiac death in recent study (unlike levo, azithro) |

| Levofloxacin | 2 | 2 | 3 | Kidney | Active (left) enantomer of ofloxacin – hence its name. How cool is that? |

| Moxifloxacin | 3 | 1 | 1 | Liver | Not active vs. Pseudomonas; generally the preferred quinolone for mycobacterial infections |

But it’s not all sunshine and happiness with these drugs. Problems:

- That nasty tendon issue

- Can make people (especially the elderly) kind of crazy – “like 5 cups of Starbucks, and not in a good way”, was one patient’s memorable description

- Photosensitivity

- QT prolongation

- Oral absorption blocked by concomitant iron, magnesium, calcium, aluminum, and probably also Krugerrands if you happen to be eating them

- C diff risk, something we really didn’t see until the emergence of the more virulent strain

- Ever rising rates of resistance with gram negative rods, Staph aureus

Bottom line? These are great antibiotics – but they are not interchangeable, and not 100% safe.

Extra credit: Can you name the five quinolones that have been pulled by the FDA for safety reasons? Double points if you get the reason they are no longer available, triple points if you also get the brand names and match them to the actual drugs.

Here’s a hint to get you started.