An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 18th, 2017

On Father’s Day, A Rumination on Families with Lots of Doctors

So was my father’s father. And my father’s uncle. And my father’s cousin.

But that’s not all. My father’s brother was also a doctor — he loved being a doctor more than anyone on the planet, and attended neurology meetings long after he retired, right up until the time he died last year.

My father’s brother-in-law (i.e., his sister’s husband) — you guessed it, a doctor.

It gets even more ridiculous. I have two first cousins who are doctors, and three first cousins married to doctors.

And I, of course, am married to a doctor myself. Her brother? A doctor.

Having all of these MDs readily available has had quite an influence on family dynamics. At one of our gatherings, my brother — not a doctor, he’s in finance — told an elderly aunt the name of the bank he was working for at the time.

Hard of hearing, she responded, “What medical school?”

These gatherings, not surprisingly, can sometimes seem more like medical grand rounds than holiday celebrations. You almost expect someone at Thanksgiving Dinner to say, “May I have the first slide, please?”

The medical profession runs so strongly in my family that at times I suspect our various dogs are, in their own doggie world, the dog-equivalent of doctors. A bit nerdy, scholarly, caring for others.

So why is it that some families take to medicine so avidly? It certainly isn’t a universal phenomenon — I routinely ask residency and fellowship applicants if there are doctors in their family, and most of them say no.

You can try researching this question, but it’s a tricky thing to search. (I tried.)

Let’s keep it simple, and list the reasons why people become doctors to begin with:

- You help people. We never really need to ask the existential question, so why am I doing this job again?

- It’s interesting. Patients, colleagues, scientific discoveries, technical challenges, policy issues — medicine is endlessly fascinating. No good doctor feels he or she has mastered their field; learning all the time is fun.

- You have a steady income. No, doctor salaries won’t touch hedge fund managers or real estate developers, or approach the revenues you might get when you sell your high tech startup to Google. And you won’t be able to afford the premiere real estate in the Bay Area or Manhattan — but let’s face it, nobody’s poor here.

- It’s prestigious. People like doctors. We might not be as popular as we once were, but it sure beats the reputation of lawyers, or politicians, or the CEO of Uber.

- You can do a lot of different things as a doctor. Aside from my wife (pediatrician) and me (ID doc), included in my family collection of doctors is a psychiatrist, a maxillofacial surgeon, an emergency room doctor, a sleep specialist, an obstetrician-gynecologist, a general internist, a nephrologist, and a Professor of the History of Medicine. I can assure you none of them does the same thing in a typical work day — yet all are doctors.

If those are the reasons why people choose medicine as a career, it still doesn’t quite explain why some families — like mine — have so many doctors.

Maybe we just suffer from a lack of imagination.

Happy Father’s Day! And yes, Dad, going to medical school was the right decision after all.

June 10th, 2017

What’s Your Favorite Antibiotic? A Fantasy Draft

Over on the journal Open Forum Infectious Diseases (that’s “O-F-I-D”, not “Oh-FID”), the generous people from IDSA and Oxford University Press have allowed me to record a series of podcasts, interviewing various interesting people in the ID field.

Over on the journal Open Forum Infectious Diseases (that’s “O-F-I-D”, not “Oh-FID”), the generous people from IDSA and Oxford University Press have allowed me to record a series of podcasts, interviewing various interesting people in the ID field.

This time, however, I strayed from the usual format and asked my colleague Rebeca Plank to join me in a “draft” of our 5 favorite antibiotics.

Which is emphatically not to imply that Rebeca isn’t interesting. On the contrary — she happens to have one of the most impressive pen collections in all of Eastern Massachusetts.

Still, you may wonder, why did we do this? Several reasons:

- We sensed a burning need for this this critical educational resource, which as you will see teaches fundamental truths about these important therapeutic tools.

- One of us wanted to honor the upcoming baseball draft (hint: Rebeca couldn’t care less about baseball).

- Someone gave me a USB microphone, and it was sitting around doing nothing for way too long.

In short, mostly we did it for fun.

Take a listen! And while you’re at it, two questions:

- What are your favorite antibiotics, and why?

- What should we draft next?

Hope you enjoy.

(H/T to Joe Posnanski and Michael Schur for the draft idea.)

June 4th, 2017

Can’t HIV Serodiscordant Couples Now Just Have Children the Regular Way?

MMWR just published a paper entitled, Strategies for Preventing HIV Infection Among HIV-Uninfected Women Attempting Conception with HIV-Infected Men — United States, and it’s both a welcome and a very strange document indeed.

It’s welcome because it acknowledges that serodiscordant couples may wish to have children without the use of an HIV-negative sperm donor. Advances in HIV prevention mean they can drop their categorical recommendation against insemination with semen from HIV-infected men, one they originally made in 1990.

But it’s strange because, right alongside treatment of the HIV-positive man with antiretroviral therapy (ART) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the woman, is a fairly lengthy data summary on “sperm washing”, a strategy many would argue has outlived its usefulness.

This is the short version of the procedure:

Another strategy that can be used in conjunction with HAART and PrEP is collection and washing of the male partner’s sperm to remove cells infected with HIV, followed by testing to confirm the absence of HIV prior to intrauterine insemination (IUI) of the female partner or in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Does one really need to put couples through this expensive and time-consuming process when the risk of transmission is unmeasurably tiny, if not zero, if the man is on suppressive ART and the woman is taking PrEP? Can you imagine the number needed to treat to prevent one additional case of HIV transmission with sperm washing in addition to ART and PrEP?

It’s like wearing a belt, suspenders, and using duct tape to keep your pants up (which is probably not the best analogy when discussing something that has to do with sex, but I’m going with it).

As a quick reminder:

- HPTN 052: Zero transmissions from infected partner if HIV RNA suppressed.

- PARTNERS Study: Zero transmissions from infected partner if HIV RNA suppressed — this while the couples were practicing “condomless sex” (otherwise they couldn’t be part of the study).

- PrEP Studies: Among adherent participants, > 90% efficacy despite high risk behavior or high community risk.

Now we don’t want to tempt the Gods of Never Say Zero with hubris about this unmeasurably low risk, but I clearly wasn’t the only one who found the paper’s emphasis on sperm washing peculiar.

Here’s a take from Ben Young, Senior Vice President/Chief Medical Officer of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care:

https://twitter.com/benyoungmd/status/870675504004648960

(“U=U” stands for “undetectable equals uninfectious”.)

Just for fun, I thought I’d check in with Pietro Vernazza, architect of the 2008 controversial “Swiss Statement” that has, for the record, turned out to be 100% correct.

Here was his response:

I was shocked about the report. In Switzerland, we have not seen any new infections among couples trying to conceive without using any additional safeguards (aside from treatment of the infected partner). The Swiss statement is very widely accepted.

And then, because what the hell, we deserve it, he added this:

But what should we say? We also don’t understand how a country can withdraw from the Paris agreement, or try to build a wall to Mexico, or to withdraw health insurance for their citizens.

Hey, I’m a huge fan of our CDC, this odd report notwithstanding. But on these issues, you’ll get no defense from me!

And just curious — is there anyone out there still strongly advocating sperm washing for serodiscordant couples wanting to have children?

Save

May 29th, 2017

Healthcare Providers Shouldn’t Come to Work While Sick, but They Do — Here’s Why

Let’s start with two questions:

- Have you ever seen a doctor, nurse, PA, pharmacist or other person directly involved in patient care wearing a surgical mask because they have a respiratory tract infection?

- Has this mask-wearing person ever been you?

Bold prediction: Virtually every reader who works in a hospital or large office practice answered “Yes” to #1. Some of you might even have said “Yes” to #2.

Clearly healthcare providers do go to work while sick, and the mask-wearing is our way of saying, “I care.”

But if we really cared, shouldn’t we just stay home?

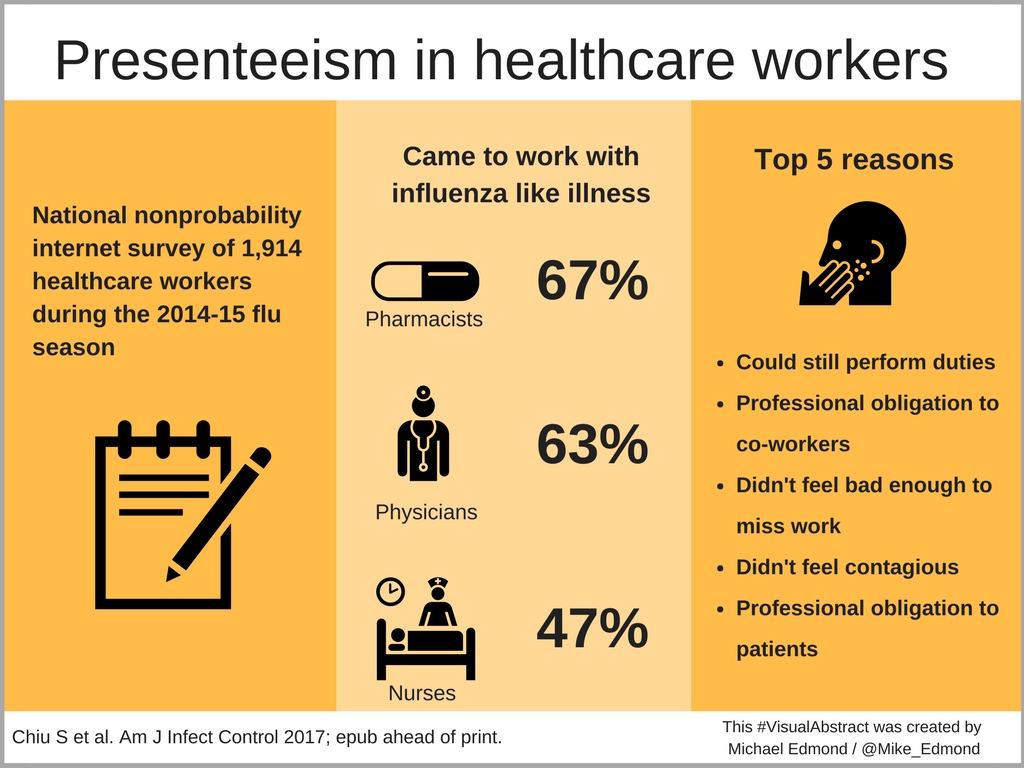

Of course we should stay home. But we don’t. Here’s a recent paper on the topic highlighted by Mike Edmond on his excellent blog, using the nifty “visual abstract” method to present the results:

Remember, surveys aren’t exactly perfect in eliciting whether people are doing some ill-advised behavior. People lie, even in anonymous polls. I know, shocking.

So consider the above estimates of this “presenteeism” a minimum. Yikes. That’s a lot of sniffling, coughing, and potentially mask-wearing healthcare providers out there.

So let’s examine the top 5 reasons why people got to work with an influenza-like illness in a bit more detail; I’ll play the part of the person choosing each response:

- Could still perform duties. Hey, does having a cold preclude me from typing and clicking boxes? That’s mostly what I get paid to do these days, right?

- Professional obligation to co-workers. Who else will do my work? And how can I ask for coverage for what might be “just a cold”?

- Didn’t feel bad enough to miss work. I told you I could type.

- Didn’t feel contagious. If I work while having a cold, I promise to double-down on the hand hygiene — you can call me “Dr. Purell” — and (though it’s embarrassing) to wear a mask. And no one really knows how long a cold is contagious. Symptoms can easily last 1-2 weeks, should I be out the entire time? Impossible.

- Professional obligation to patients. My patients will be mad if I don’t show up. They would prefer to see a sniffly, red-eyed, coughing me than a covering clinician, or to wait a week until I’ve recovered. And obviously no one can provide the brilliant, compassionate, and efficient care that I do.

Jokes aside, presenteeism gives infection control practitioners a major challenge. It’s even more intractable when you factor in the most common reason cited by healthcare providers at long-term care facilities, which is the inability to afford lost pay.

One practical problem we could work on is directly related to reason #4, “Didn’t feel contagious.”

While it’s intuitively obvious that a healthcare worker with pulmonary tuberculosis, active salmonellosis, or highly symptomatic influenza shouldn’t be working, what about milder illnesses that can, in certain hosts, be life-threatening? Thinking about you, RSV, adenovirus, and parainfluenza virus.

Perhaps it’s time we all got a multiplex PCR machine for home use. It would look great in the living room.

Save

May 21st, 2017

The Curious Case of M184V, Part 1

Thanks to our sophisticated research team here at NEJM Journal Watch, we have an excellent idea who reads this thing for its scintillating ID/HIV content.

Thanks to our sophisticated research team here at NEJM Journal Watch, we have an excellent idea who reads this thing for its scintillating ID/HIV content.

Most of you are clinicians — doctors, nurses, PAs, PharmDs. A smaller proportion are researchers, lab-oriented types who wandered over here unexpectedly after an errant search, expecting the latest in CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and instead getting an ID Link-o-Rama, a rumination on vintage medical photos, and a mysteriosis about listeriosis.

But another divider is whether you consider yourself an HIV specialist or not. A grab bag of ID (mostly), primary care, and other subspecialty clinicians, HIV specialists know and ruminate over lots of the same stuff even though there’s no formally designated HIV specialty by the American Board of Internal Medicine.

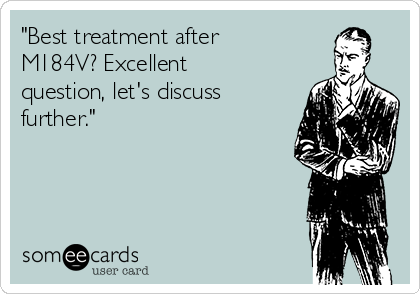

And today’s topic is most definitely an HIV-focused one, triggered by an email I received last week from one of my colleagues:

Subject: M184V

Paul,

What’s your go-to regimen in the setting of a solo M184V?

Jon

For the non-HIV specialist readers, allow me to decipher the code in the above question. “M184V” is the shorthand for methionine replacing valine at position 184 in reverse transcriptase. It is by far the most commonly encountered nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) mutation after failure with regimens containing lamivudine (3TC) or emtricitabine (FTC).

And with that single paragraph, I’ve hinted why HIV drug resistance — and genotypes in particular — baffle some of even the most astute and brilliant ID clinicians. It’s like reading about the coagulation cascade or the complement system. You have to work with this stuff frequently to understand the lingo.

But for those seeing HIV patients on a regular basis (especially as outpatients), this question — what should be done after M184V? — is both quite relevant clinically and, surprisingly, not readily answerable from the literature.

Remember, M184V is a special mutation — it does some very weird things:

- Viruses that harbor M184V don’t replicate well. In virology parlance, they’re “less fit.”

- M184V causes marked phenotypic resistance to 3TC/FTC, but this doesn’t translate clinically. Or, to cite the invaluable Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database, “M184V/I are selected by 3TC/FTC and reduce susceptibility to these drugs >100-fold.” For an analogy, think of high-level gentamicin resistance in an enterococcus isolate — but then ignore it and use gentamicin anyway. Because unlike these enterococci, where gentamicin would be useless, studies show that 3TC still exerts significant antiviral activity despite this loss of phenotypic activity. I’ve cited these studies before, but they deserve emphasis: Virologic rebound occurred after stopping 3TC in patients who already had developed M184V; and 3TC alone slowed CD4 decline more than no treatment despite M184V being present in all patients.

- M184V influences the in vitro susceptibility of certain other NRTIs in a favorable way. Yes, with M184V, susceptibility to tenofovir, zidovudine, and stavudine improves. In other words, an M184V containing virus is more susceptible to tenofovir than a wild-type virus, a phenomenon referred to as hypersusceptibility. Someone much smarter than I can explain the molecular mechanism of this phenomenon (it certainly won’t be me).

Because of these odd effects, and because both 3TC and FTC are so well tolerated, there’s a practice (not universally observed) of continuing 3TC or FTC even after M184V has been selected. But should this be done?

And with that background, let’s get back to the question in Jon’s email — what to do after M184V?

Imagine this case — a patient who failed a regimen of dual NRTIs plus an NNRTI (let’s say TDF/FTC/EFV) some time in the past. He had a genotype then showing M184V and K103N (conferring resistance to efavirenz), and then was lost to follow-up for a few years.

He now shows up saying he wants to start treatment again. Let’s give him a CD4 cell count of 250 and a viral load of 50,000. He of course wants as few side effects, and as few pills, as possible.

What would you choose as his antiretroviral regimen?

May 14th, 2017

Poll: Which Feature of Electronic Health Records is Most Important to Patient Care?

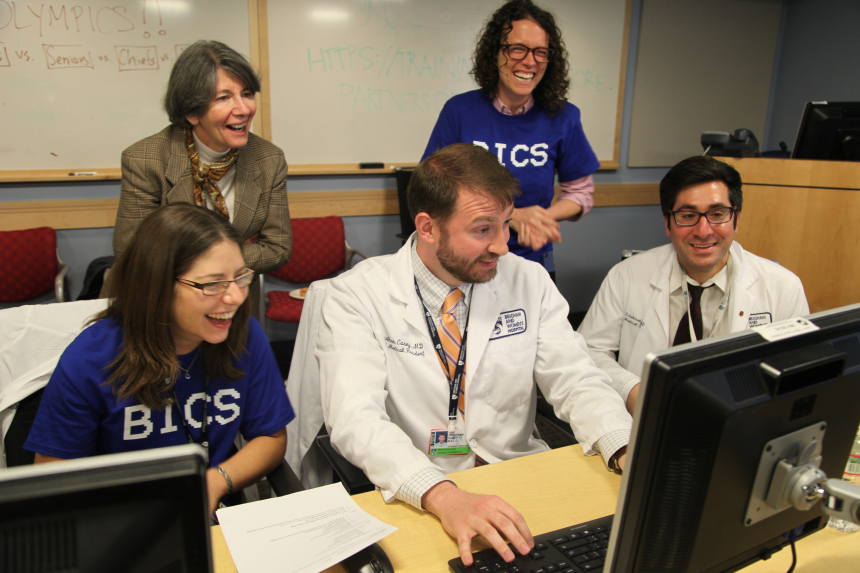

The first electronic medical record I used regularly — called “BICS” — initially had one purpose. It was a tool to look up a patient’s lab results.

The first electronic medical record I used regularly — called “BICS” — initially had one purpose. It was a tool to look up a patient’s lab results.

Simple, reliable, and blazingly fast, it did one thing remarkably well.

Later, one of our Emergency Department doctors, who happens to have impressive coding skills, worked with a team to add a simple ambulatory medical record (medications, allergies, a problem list, progress notes).

Soon after, they released an astonishingly efficient inpatient order entry system, one that relied on keyboard shortcuts. Use of the mouse was definitely for amateurs.

After a brief learning period that took the interns around a nanosecond, all the clinicians loved it. It was so popular that the medical housestaff even held a party in its honor, something they called “OlymBICS,” with teams competing to see who could enter orders the fastest.

Much of its success, I’d argue, had to do with the simplicity — it didn’t overreach. Today, of course, all the big EHRs (or EMRs, or whatever you want to call them) try to do all things for all people — doctors, nurses, patients, administrative staff. I wouldn’t be surprised if there are features for the hospital cafeteria and catering services.

And because the range of these activities is so broad, EHRs have become bloated, complex, and inefficient. The complexity steals attention away from our patients as we try to satisfy the insatiable screen, keyboard, and mouse.

There’s just so much to do (and so many opportunities to do it wrong), it’s hard to concentrate.

In a piece called “Death By A Thousand Clicks,” some local colleagues write the following:

It happens every day, in exam rooms across the country, something that would have been unthinkable 20 years ago: Doctors and nurses turn away from their patients and focus their attention elsewhere — on their computer screens … EMRs have become the bane of doctors and nurses everywhere. They are the medical equivalent of texting while driving, sucking the soul out of the practice of medicine while failing to improve care.

Yes, we all recognize that feeling!

These problems notwithstanding, it’s clear that not even the crankiest EHR critic would propose that we go back to the days of paper charts, radiology film libraries, or having to call the lab to get patient test results.

Part of what makes the problems with EHRs so frustrating is that there is so much potential for excellent, intuitive, and interoperative systems. EHRs already do some things very well indeed.

The British struggled when their EHRs went down in the recent WannaCry cyberattack, and not just because they were still using an unpatched version of Windows XP.

(XP? Seriously? Yikes.)

So to detail the EHR benefits, and in honor of BICS (may it R.I.P.), I list below several widely available EMR functions.

You, dear reader, will choose the one feature you would miss the most during patient care if it suddenly were no longer available. In the comments section, feel free to elaborate why you chose what you did.

And I’m pretty sure I can predict the loser of this poll.

Save

May 7th, 2017

CRISPR and HIV “Cure,” Zinc for Colds, New AIDSInfo Site, CROI Dates, Vanco Pricing, and More: I Can’t Believe It’s May ID Link-o-Rama

A few Infectious Diseases/HIV items to consider as we wait (and keep waiting!) for the warm weather to arrive in chilly, and often wet, New England:

A few Infectious Diseases/HIV items to consider as we wait (and keep waiting!) for the warm weather to arrive in chilly, and often wet, New England:

- CRISPR-Cas9 excises latent HIV from the cells of humanized mice. With the usual caveat about not overreacting (like this) to an animal model, this CRISPR strategy seems like a more viable HIV cure intervention than other approaches. Nonetheless, we still have a long way to go before something like this is tested in humans and deemed to be safe.

- Zinc might shorten the duration of cold symptoms after all. Time for a fully powered, randomized, double-blind trial!

- Do the rare late relapses after HCV cure warrant checking HCV RNA a year after completing therapy, and not just at week 12? These guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association Institute state that “some clinicians may think it prudent.” (Read that with a George Bush Sr. accent, via Dana Carvey.) Probably the best reason to re-check HCV RNA is to document re-infection, not a relapse. Regardless, this strategy does make sense.

- Largest measles outbreak in Minnesota in decades sickens children, leads to hospitalizations. (Edit: Excellent original coverage here, including comments from discredited vaccine researcher Andrew Wakefield, who states, “I don’t feel responsible at all” for the outbreak. Good grief.) And another outbreak in Portugal led to the death of a 17-year-old girl. Wouldn’t it be great if we had a simple, effective way of preventing measles? Oh, wait.

- The AIDSinfo site has been extensively updated. Well worth checking out for all your guidelines, patient information, and educational needs. Mobile apps, too. One pet peeve — I prefer “ART” over “ARV” as an abbreviation for “antiretroviral therapy.” How about you? Let’s do a poll:

Quick poll:

What abbreviation do you prefer for "antiretroviral therapy"?

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) May 7, 2017

- Tick-related illnesses could be a particular problem this year. Mice + Acorns = potential explosion in tick population. Get that doxycycline ready.

- One penicillin dose for early syphilis in people with HIV is good as three. More is not always better. And isn’t it extraordinary that Treponema pallidum still hasn’t figured out how to develop resistance to penicillin?

- This superb review of the book Drug Dealer, M.D skillfully outlines how we got into this opiate addiction mess. I kept nodding with agreement while reading this piece by my friend and colleague Abbie Zuger. I think it should be required reading for all current doctors, nurses, PAs, PharmDs, as well as students of these healthcare professions.

- The Massachusetts Medical Society voted to support medically supervised safe injection sites. There is excellent evidence from Europe and Canada that these sites save lives, clean up the streets and parks, and offer people with addiction information on how to access treatment. The idea has support from our local paper, too. Now, will it actually happen here? Currently there are zero in the USA. We are, as a society, very paranoid about “enabling” risky behavior by making it safer.

- Wonder why oral vancomycin is still so expensive despite having multiple generic manufacturers? Me too — the linked review covers this unique (and frustrating) situation, one that highlights the oddity of drug pricing in the USA and hints at price collusion.

- Worthy long-read: This fascinating profile of AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s director, Michael Weinstein. Ironically, the piece reminded me of another powerful person in the annals of HIV treatment, only in a completely different area — organic chemist Ray Schinazi. Both elicit strong reactions, pro and con.

- The 2019 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) will take place in Seattle, March 4-7. The date and location of this important meeting used to be the best-kept secret in Infectious Diseases, which made creating academic schedules a nightmare. Vastly prefer this advance notice!

- This drug name emoji game is awesome. I selected every ID doctor’s favorite antibiotic for display up at the top of the post. It should prove especially useful for this bad upcoming tick season. And imagine if this is how we had to write prescriptions.

OK, now for a quick non-ID section:

- Here is a spot-on criticism of the “Milestones” process for evaluating medical residents and fellows. These ACGME Milestones offer a perfect example of how quantifying skills for which there are no reliable metrics leads to distracting noise, not real data. We got much more valuable information in the past when resident evaluations were done by narrative, using actual language rather than checking boxes.

- The New York City Department of Public Health keeps meticulous records of dog names. Bella is right now #1 for females, Max for males. And it looks like Nellie is very popular in my parent’s neighborhood. Just so you know.

https://twitter.com/HelenBranswell/status/860553983718563845

- If you have even the slightest interest in baseball, I strongly recommend the book Smart Baseball, by Keith Law. Did you know that batting average, RBIs, and pitcher wins are highly flawed measurements of a player’s ability? And that you should never bunt solely to advance the runner? That the pitcher “save” is an evil force in the game? All 100% true, and clearly and entertainingly explained. I can also strongly endorse the author’s excellent blog, where he writes about books, food, movies, and is a consistent and forceful defender of the importance of vaccines for personal and public health. We like that!

- The television series “American Crime” is outstanding, but hardly anyone is watching. Despite critical acclaim, the ratings are only fair — seems like a quality/ratings ratio on par with “Friday Night Lights,” another terrific series that was relatively ignored when it aired. The linked piece places some of the blame on the rather blah and misleading title, a very good point.

Hey, I started with CRISPR/Cas9, so here’s the big finish. Take it away, A Capella Science!

April 30th, 2017

Celebrating the Invaluable Knowledge and Expertise of ID Specialist PharmD’s

Since expression of gratitude makes you happier — hey, I read it on the internet — and whining does the reverse, I’ve decided to turn what was going to be a typical rant about dealing with insurance companies into an expression of thanks to a remarkable group of professionals.

Namely, the Doctors of Pharmacy (PharmD’s) who specialize in Infectious Diseases. About whom I am extremely, exceedingly grateful.

And I’m not alone in holding that view — you’ll find it’s universal among ID doctors who are lucky enough to work with one or more ID PharmD’s, whether it’s as part of an antibiotic stewardship program, an HIV or transplant clinic, or on the inpatient ID consultation service.

Although I could cite numerous examples of how the two primary ID PharmDs help us out (thank you Dave and Brandon!), here’s a recent case from my outpatient practice.

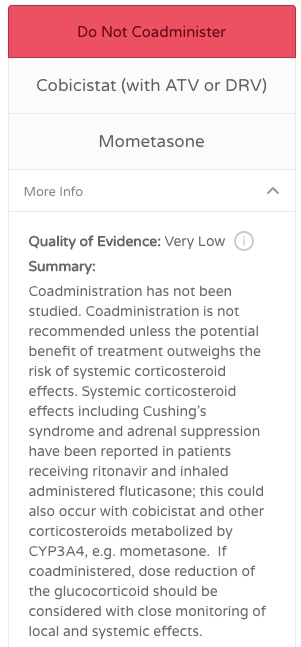

A patient of mine, receiving TAF/FTC, darunavir/cobicistat for HIV treatment, needed a nasal steroid inhaler for seasonal allergies. For the non-HIV specialists, recall that when inhaled, injectable, or even topical corticosteroids are given with these potent cytochrome p450 inhibitors, systemic levels of cortisol can dangerously increase.

Result: Full-blown hypercortisolism (Cushing Syndrome), which usually takes months to resolve and can leave permanent damage. This ritonavir/cobicistat-inhaled steroid interaction is emphatically not one of those EHR alerts to ignore.

So this isn’t a simple matter of telling him to go grab whatever over-the-counter spray is on sale at his local CVS or Walgreens. As a result, I sent a prescription to his pharmacy for beclomethasone because it can be safely given without interacting with cobicistat or ritonavir.

Per his insurance pharmacy benefit manager, however, they wouldn’t cover the beclomethasone. They sent along an annoying notice about “formulary alternatives”, specifically:

… flunisolide spray, fluticasone spray [hey guys at insurance company, this is the WORST POSSIBLE SUGGESTION!], mometasone spray, or triamcinolone spray.

So what to do? Obviously fluticasone would be a terrible option. Furthermore, I’ve seen iatrogenic hypercortisolism several times after triamcinolone injections, so cross that one off the list too.

So what to do? Obviously fluticasone would be a terrible option. Furthermore, I’ve seen iatrogenic hypercortisolism several times after triamcinolone injections, so cross that one off the list too.

What about mometasone? UpToDate has an easy-to-use drug interaction program, and it showed no significant interaction. However, the invaluable University of Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions checker disagreed, and did so strongly (that’s their report to the right).

This left flunisolide, which for some reason isn’t listed on the Liverpool site. At this point, I needed help with determining whether flunisolide would be safe to administer with cobicistat. Cue up the query to our ID PharmD’s.

Shortly after sending an email, I received the following incredibly helpful response:

Hi Paul,

Beclomethasone is the only corticosteroid that has been shown to have no clinically significant interaction, likely due to the fact that it is not primarily metabolized by CYP3A4. Flunisolide is also not primarily metabolized by 3A4 and has similar physicochemical properties as beclomethasone (less systemic absorption and more highly protein bound) — here’s a good review. Theoretically it would have the lowest likelihood of an interaction out of the alternatives they recommended, but there are no studies or case reports of flunisolide use with ritonavir or cobicistat. If you decide to prescribe flunisolide, you could start at the initial dose of 2 sprays in each nostril BID, which is half of the maximum dose of 8 sprays in each nostril daily. Let me know if you have any further questions.

Brandon

Thank you, Brandon!

And to the other ID PharmD’s out there, thanks for the advice on the innumerable other drug interactions, for guidance on dosing in renal failure, for questions about formulations (about which doctors know shockingly little), for interpretation of voriconazole, vancomycin, and aminoglycoside levels, for researching adverse drug effects — and for the whole gamut of expertise you bring to our specialty.

April 22nd, 2017

If United Airlines Ran Your Doctor’s Office Practice

Man Dragged from Doctor’s Office Exam Room; Investigation Ongoing

April 22, 2016

MIDDLETON, MINNESOTA — Mr. Thomas Anderson was scheduled to see Dr. Wilson Smith yesterday for evaluation of low back pain.

He left his appointment with considerably more than that.

In a bizarre series of events that Middleton law enforcement officials are still investigating, Anderson sustained facial injuries and bleeding when he was forcibly dragged out of Smith’s office by security guards when he refused to leave voluntarily.

Meanwhile, startled patients in the waiting room filmed the disturbing event on their cell phones. The videos were posted on Facebook and Twitter, quickly eliciting a chorus of outraged comments, all supporting Anderson’s right to stay.

“I’d been waiting for this appointment for weeks,” said Mr. Anderson from his hospital room, where he is being treated for facial injuries and a concussion. “They had already put me in the exam room, collected my co-pay, and asked me to change into this skimpy gown. No way I was going to leave.”

The problem began when Dr. Smith, who works for United All Life (UAL) Health Corporation, was contacted by the CEO of the company stating that four UAL employees needed to be seen urgently. But when Dr. Smith checked his afternoon schedule, he noted he was completely booked.

Based on policies outlined in a 5,000 word document that UAL patients sign when agreeing to care, the company has the right to deny services based on overbooking — or, in the case involving Anderson, when UAL employees require care.

The policy does say UAL must offer compensation to patients in exchange for being “bumped” from their scheduled visit. Three of Dr. Smith’s other patients agreed to reschedule their medical appointment when told they would receive a $25 Amazon gift card and a $10 discount at Panera (provided they spend at least $20 on food or beverages).

When Mr. Anderson refused the same offer, UAL upped the compensation to include 2 matinee passes to see Smurfs: The Lost Village. “Those passes are good at any theater,” said Ms. Jenna Gormley, a spokesperson for UAL. “We take our company motto — ‘Get the Friendly Care of United’ — seriously.”

But Mr. Anderson, who is 66, said he had little interest in seeing the latest Smurfs movie and still refused to leave. That’s when Dr. Smith called the security guards, who made the term “bumped” literal.

Middleton law enforcement is now investigating the criteria UAL uses to choose which patients are to be “re-accommodated” under these circumstances.

Most of the other patients on Dr. Smith’s schedule that day had “Elite” status based on paying a higher fee at the time they booked their appointments. This payment allowed them to bring one item (such as a purse or a backpack) and a coat with them to the doctor’s office without incurring extra charges.

Elite patients also had access to more comfortable chairs in the waiting room. Mr. Anderson, who chose not to pay this fee, says he was told by Dr. Smith’s receptionist that he had to sit on a hard stool in the corner, face the wall, and put on an embarrassing hat.

When asked further about these policies, UAL’s Gormley responded, “At UAL, our first priority is always our patients’ safety.”

She then was completely unable to explain how this statement could possibly be true.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jqu7-XJEXVk&w=560&h=315]

Save

April 16th, 2017

Mark Wainberg and the Enduring Importance of 3TC

Last week, the HIV/ID research world lost one of its leaders and pioneers when Dr. Mark Wainberg unexpectedly died. An astute, thoughtful virologist — and a warm, engaging person — he led the HIV research program at McGill University in Montreal for years, contributing to the field both through his research and patient advocacy. A strong voice in the effort to expand HIV therapy to Africa in the early 2000s, Mark was also a vocal critic of HIV denialism.

Last week, the HIV/ID research world lost one of its leaders and pioneers when Dr. Mark Wainberg unexpectedly died. An astute, thoughtful virologist — and a warm, engaging person — he led the HIV research program at McGill University in Montreal for years, contributing to the field both through his research and patient advocacy. A strong voice in the effort to expand HIV therapy to Africa in the early 2000s, Mark was also a vocal critic of HIV denialism.

If I had to single out one notable achievement, however, it would be this:

Then, in 1989, after studying the properties of a new antiviral drug called 3TC, or lamivudine, Dr. Wainberg found that it was effective against H.I.V. It soon became an important part of the so-called AIDS cocktail of drugs that is still used to treat infected patients.

This, of course, just hints at the critical role this drug has had in the success of HIV treatment. 3TC is the long-term superstar of the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) class, a characteristic it shares with the similar (and somewhat more potent) emtricitabine, or FTC.

Here are some of the highlights:

- Triple-therapy consisting of AZT, 3TC, and indinavir demonstrated durable virologic suppression for the first time. The protease inhibitor indinavir got lots of the credit for the success of this strategy since it represented a new drug class, but in these AZT-experienced patients — many of whom likely had extensive AZT resistance — the addition 3TC was arguably just as important.

- Resistance to 3TC improves susceptibility to AZT, d4T, and tenofovir. Having no resistance is clearly the best scenario, but if you have to have one resistance mutation, let it be M184V. This phenomenon could explain at least in part the results of the above study, or the ongoing benefit of recycled NRTIs in second-line trials (EARNEST, SECOND-LINE), where the activity of the NRTIs appears comparable to raltegravir — even though the latter is a new drug class.

- Resistance to 3TC isn’t really resistance after all. Despite massive phenotypic resistance to 3TC measured in vitro with viruses harboring the M184V mutation, several studies have demonstrated the ongoing antiviral effect of the drug anyway. In one study, stopping 3TC in patients with M184V led to prompt virologic rebound. In this other study, 3TC monotherapy delayed CD4 decline and virologic rebound compared with complete treatment interruption. Is it that M184V reduces viral fitness? That our phenotypic assays are wrong? Does it matter?

- Pretty much every “winner” in comparative clinical trials contains 3TC or FTC; conversely, strategies without these drugs often lose. There are so many examples it would take me a week to go through them all. Instead, I’ll just repeat the brilliant comment from Joel Gallant on this topic: “The best nuke [NRTI]-sparing strategy contains a nuke.”

- 3TC might be the key component to successful 2-drug therapy. The GARDEL study of LPV/r plus 3TC was the first hint that this strategy could break the rule that combination therapy must contain three active drugs. This success has now been followed by studies in virologically suppressed patients “deintensified” to a boosted PI (LPV/r, ATV/r, or DRV/r) plus 3TC, each demonstrating ongoing virologic success when the third (non-3TC) NRTI was dropped. Since boosted PIs are no longer first-line therapy, an important question is whether the same success will be seen with DTG plus 3TC — studies are ongoing.

Of course none of the above success with 3TC or FTC containing regimens would be possible were the drugs not extraordinarily well-tolerated. This safety profile makes 3TC among the few drugs approved in the 1990s still in wide use today.

We will very much miss Dr. Mark Wainberg. His legacy lives on with the people he trained, his extraordinarily productive research career, the expansion of HIV treatment globally — and with the miraculous drug 3TC.

Save