An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

February 21st, 2021

Why Are COVID-19 Case Numbers Dropping?

We don’t know. That part is easy.

Also easy is that case numbers really are falling — it’s not just reduced testing — and it’s happening pretty much everywhere.

Urban areas and rural. Red states and blue. Places with broad vaccine rollouts and those with hardly any. North and South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Even countries with the B.1.1.7 variant.

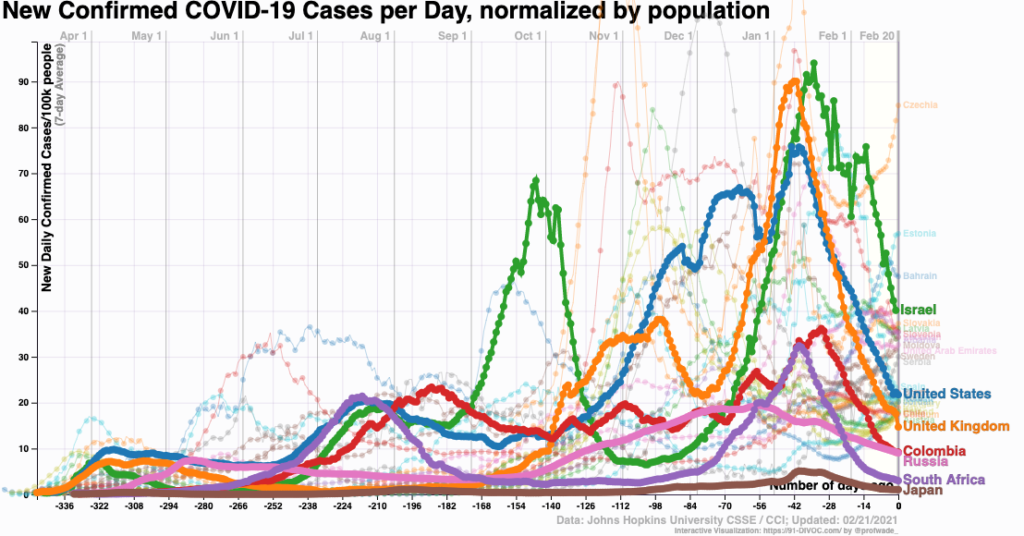

Look:

Let’s round up some theories:

1. Seasonality. An attractive hypothesis — coronavirus infections pre-SARS-CoV-2 definitely show a seasonal pattern.

And various viral diseases go through communities synchronized with the seasons, especially when school starts or the weather gets colder. Any pediatrician will tell you that.

Note that the term “seasonality” has always been a bit misleading — it refers to infections peaking within seasons, not throughout them. Think of influenza, how sometimes we have an early, sometimes a late seasonal peak in the winter.

The problem with this seasonality theory is that the seasons are flipped in the southern hemisphere. And didn’t cases surge over the summer in many southern U.S. states?

2. Herd immunity. Nearly 28 million Americans have had a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis reported to the CDC. This represents only a fraction of the true cases — especially the mild or asymptomatic ones — and the CDC estimates that only 1 in 4.6 infections are reported. That could bring us up to half the US population with some degree of natural immunity to infection.

Even as of mid-January, the CDC put the actual case numbers at over 80 million, and certainly it’s higher than that now. And note that in some regions, the actual case counts might be even higher — 5 to 20 times higher, according to one recent publication.

3. Behavior. We know much better now how this virus is transmitted. Avoiding crowds and indoor spaces with poor ventilation — and wearing masks — reduce the risk. But has our behavior actually followed suit?

The holidays are behind us. The Super Bowl was lousy. Not many parties for the Australian Open tennis finals. Spring Break hasn’t happened yet.

One compelling hypothesis, related to herd immunity, is that the people least likely to follow infection control advice — or unable to follow it based on work or living situation — already have had COVID-19 and hence are immune.

The others, not yet infected, watched cases surge in December and January and continue to hunker down and stay safe — or again, have the luxury of staying safe. They might be especially vigilant now that a vaccine is in their not-too-distant future — you know, the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, the light at the end of the tunnel, or the Holy Grail at the end of the Monty Python movie.

(Sorry about that.)

4. Vaccines. The world is vaccinating like crazy. Demand is off the charts. And in most places, we’re targeting the people most likely to have symptomatic or severe disease.

Plus, the data increasingly suggest that the vaccines reduce not just disease, but also the likelihood of transmission — they reduce infections overall (uninfected people can’t transmit), and those with infection have lower viral loads.

While the vaccine rollout is not yet broad enough to explain the case number drop on its own, it might be contributing. It certainly could be playing a role in Israel.

5. The virus. Maybe the virus is doing us a favor and becoming less virulent over time. Perhaps some of these variants — if not B.1.1.7 — in order to gain the ability to transmit, also cause less severe disease.

Take the virus’s perspective — yes, think like a virus — and how this would be evolutionarily beneficial. More mild cases, more chance to spread its genetic material to other susceptible hosts. That’s all viruses care about, right?

6. It’s a gemish. This brings us to the most likely explanation for the drop in cases, a gemish — Yiddish for a mixture of things. (It’s pronounced “ga-mish”, in case you want to try it out on your own.)

It could be all of the above explanations, in various proportions, and different in various regions — plus things no one has considered.

And the uncertainty about why cases are dropping again hearkens back to this great H.L Mencken quotation, which over time has morphed into this profound statement:

Every complex problem has a solution which is simple, direct, plausible — and wrong.

I stress the importance of being humble about not knowing why the cases are dropping simply because reliance on one of these factors over another could get us into trouble. For example, this week Dr. Marty Makary, writing in the Wall Street Journal, posited that we are already close to herd immunity, making this bold prediction:

There is reason to think the country is racing toward an extremely low level of infection. As more people have been infected, most of whom have mild or no symptoms, there are fewer Americans left to be infected. At the current trajectory, I expect Covid will be mostly gone by April, allowing Americans to resume normal life.

Warning — if anyone tells you with confidence that they know precisely why cases are dropping, and that they have an accurate crystal ball showing that by April we’ll be safely out of this pandemic — please view it with the appropriate scientific skepticism it deserves.

Look, we can hope this optimistic prediction is correct — we all want that. April isn’t far away, we’ll know soon.

But if there’s one thing a pandemic from a new human disease teaches us, it’s that there’s a lot we don’t know.

February 15th, 2021

Time to Fix the HIV Testing Algorithm — and Here’s How to Do It

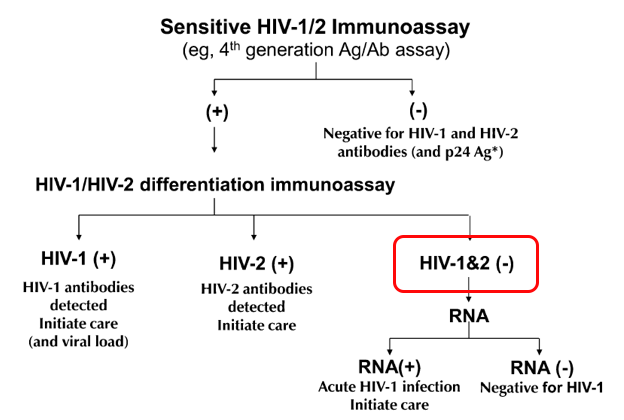

Remember the revised HIV testing algorithm that debuted in 2014? The one that was supposed to solve all our problems?

First, it included a “highly sensitive” screening test that started with a “4th Generation” combination antibody/antigen test. This decreased the window period between acquiring HIV and having a positive test, thanks to the antigen. Great!

(These “generation” analogies sure are common in medicine. Is there a line of inheritance? A royal family? Some black sheep?)

Second, it retired the HIV Western blot as the confirmation test, and substituted a “differentiation assay”, a test that distinguishes between HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies. This test is cheaper, faster, more sensitive, and automated, many advantages over the Western blot — may the latter R.I.P, it served us well for many years.

Hooray! All problems solved. A highly accurate diagnostic test in ID just got even better.

Well … not quite. The algorithm improved, but a major problem remained — what does it mean when a highly sensitive fourth-generation test comes back positive, but the differentiation antibody assay is negative?

In graphic form, this:

These indeterminate results are so frequent that it motivates by far the most common question we ID doctors receive about HIV testing — and was the subject of one of the most popular pre-pandemic posts ever on this site.

The problem is that these results represent two clinical states that are diametrically opposite:

- Acute HIV — a person who recently acquired HIV, and is still in the “window period” before antibody develops. Remember, the differentiation assay is an antibody test. It takes a while to turn positive, typically 2-4 weeks.

- False-positive HIV screen — a person who doesn’t have HIV at all.

In most clinical settings, the second of these (the false-positives) greatly outnumber the acute HIV cases. But we still have to bring back the patient to rule out acute HIV.

Which is a pain, and creates several more “worry days” before there is diagnostic certainty.

Ah, but what if you could just do an HIV RNA assay — a viral load — as the confirmatory test? And potentially not have to bring the patient back in at all?

Such a strategy is now feasible using one of the HIV viral load assays, the Aptima® HIV-1 Quant Dx. It’s the first quantitative viral load test that is also approved for diagnosis of HIV. Off a serum sample sent for HIV screening, the lab can run a qualitative HIV viral load with this assay, with results as follows:

- Non-reactive for HIV-1 RNA, or

- Reactive for HIV-1 RNA

The lab can detect whether the reactive test was < 30, between 30-10 million copies/mL, or >10 million — but the package insert says it won’t report those ranges, since the test isn’t approved this way.

(I should mention here that long-time HIV testing guru Bernie Branson says that says that the assay can report an actual number off of serum, albeit one that is likely lower than we get from plasma. Which makes us wonder whether a plasma sample can be collected for HIV screening, and reflexed to the accurate quantitative viral load — the subject of a collaborative modeling study led by my colleague Dr. Emily Hyle.)

With the HIV RNA as the confirmatory test, the vast majority of reactive HIV screens could quickly be resolved — a non-reactive result would be all but 100% reassurance that the screening test was a false-positive. And a reactive result would mean that person has HIV, and should start ART.

The differentiation assay will still be run if the HIV RNA is negative, as it will determine whether a person is either an HIV controller (has HIV with an undetectable viral load), or has HIV-2. But both are pretty darn rare.

So let’s go back to the confirmatory HIV RNA being reactive. Would this be sufficient information to start treatment, or would clinicians still want to collect a baseline quantitative result, then start ART?

I wondered about this, so here’s a little poll:

Hey #IDtwitter — if the HIV testing algorithm went like this:

1) HIV Ag/Ab screen – Reactive

2) HIV RNA confirmation – Reactive for HIV RNA (range 30-10 million)

Would you still send a quantitative VL before starting ART? Why or why not? @EmilyHyle @Hologic— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 13, 2021

A solid majority would still want this quantitative result, even while acknowledging it’s unlikely to change most initial treatment strategies. Here’s one of the best reasons why from Dr. Hana Akselrod:

Patients have mentioned the emotional impact of seeing the VL number come down by orders of magnitude, so that is now part of my motivational interview. Then we segue into U=U.

I agree!

Plus, HIV experts will note that two initial regimens — DTG/3TC and tenofovir/FTC/RPV — also have upper limit viral load thresholds that exclude them as options. (For these two, it’s 500,000 and 100,000, respectively.)

However, from a medical perspective, knowing the precise quantitative viral load usually would fall more into the “nice to know” than “need to know” category.

I’d bring the person back for a resistance genotype (another “nice to know” test) and a plasma quantitative viral load, and start ART (generally bictegravir/FTC/TAF or dolutegravir plus tenofovir/FTC) awaiting the results of these tests.

To summarize, it makes all kinds of sense to use an HIV RNA as the confirmatory test after a reactive HIV Ag/Ab screening test. It will reduce both “worry days” for those who test negative and speed up the time to starting HIV therapy for those who test positive.

Even better? Collect a plasma sample for the HIV screening test, and then use that for a precise quantitative viral load if the screen is reactive.

Now when can we make this change?

And since I haven’t featured a video in a while, how about this one, sent to me by a noted (but now retired) food journalist? How can you resist Weird Stuff in a Can?

We hope you enjoyed this week’s break from relentless 24/7 COVID-19 coverage. Have to mix things up a bit. Thank you for your understanding.

February 7th, 2021

Does Taking Vitamin D Prevent or Treat COVID-19?

Vitamin D supplementation — critical in prevention and treatment of COVID-19?

Or does it do nothing — except further enrich the vitamin and supplements industry, which is worth more than 100 billion dollars?

The challenge is figuring out which of these is the truth, and after several weeks of thinking about the issue, I find it’s far from straightforward — with many strong (and conflicting) opinions held by lots of smart people.

I waded into these choppy waters a couple of months ago with this post after seeing a pre-print of a negative vitamin D study:

Low vitamin D levels may correlate with worse outcomes in many diseases.

But supplementing does not necessarily improve outcomes. In fact, it almost never does.

(Still waiting for a truly convincing study in any infection.)

Lather, rince, repeat.https://t.co/RlqpSCPlRC

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) December 8, 2020

You can tell what my “priors” were on this research question. Most studies of vitamin supplementation in all diseases have ended with negative results — it’s really quite remarkable the sheer number — and in some medical problems the vitamin treatment arm actually does worse.

For vitamin D specifically, here’s a list of the negative randomized clinical trials done just in the past couple of years summarized by NEJM Journal Watch:

- Prenatal supplementation and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children

- Falls in older adults

- A range of physical and cognitive outcomes in adults older than 70

- Macular degeneration

- Bone density (this one surprised me)

- Childhood asthma

- Preventing depression in adults 50 and older

- Preventing TB in children

- Outcomes in critical illness

- Diabetes-related kidney function

- Bone density (again!)

For each of these disease areas, observational studies found an association between low vitamin D levels and poor outcomes, with a mechanistic explanation of why that might be, and how such adverse outcomes could be reversed with supplements.

But alas, all of the randomized trials were negative — no significant benefit. Not only that, the study on falls in older adults and one of the bone density studies actually showed worse outcomes with higher doses — never a good trend.

But I quickly learned that despite these negative studies, my skeptical view about vitamin D and COVID-19 is far from universal.

Indeed, the response to the post was surprisingly brisk, and quite polarized — some agreeing with the post that “association is not causation — basic principles.”

Others criticized the study design, in particular the eligibility criteria (too sick) and dosing strategy (daily dosing would be better). Someone sent me this hour-long video, a tour-de-force graphical explanation of how vitamin D is critical for prevention and treatment of COVID-19; another person sent this “Roll Call” of credible experts calling for vitamin D treatment.

Then a physician I know well from teaching together (a primary care doctor) sent me a 2017 meta-analysis of randomized trials on vitamin D supplementation to prevent viral respiratory tract infections. The studies included are mostly of good quality, and the aggregate results suggest a substantial benefit.

Perhaps this is why Tony Fauci says he takes a vitamin D supplement?

Now motivated to learn more, I reached out to Dr. David Meltzer from the University of Chicago. He’s the first-author on a nicely done study finding a strong association between low vitamin D levels and testing positive for COVID-19, and he kindly agreed to be interviewed in this OFID podcast about this paper and his ongoing studies. Highly recommended — he’s a smart, experienced clinical researcher, doing community-based randomized trials of various vitamin D interventions.

And there’s quite a bit of other research going on right now, as summarized nicely here in this review by Rita Rubin in JAMA. She also cites some inconsistencies in the research to date, along with a discussion of the funders of some of the trials — not surprisingly, companies from the supplements industry and labs that offer vitamin D tests.

So where do I stand on this vitamin D issue?

It seems highly likely that low vitamin D levels are associated with worse outcomes in COVID-19. Levels are a marker for various components of ill health — inactivity, poor nutrition, lack of fresh air and sunshine.

Conversely, taking vitamin supplements in observational studies often is associated with better outcomes. Whether this is because such people are more health-seeking, or whether the supplement is doing anything, isn’t possible to disentangle. For a perfect example, here’s a recent study showing that regular supplement takers of vitamin D were less likely to get diagnosed with COVID-19. But the benefit didn’t appear to be mediated by higher vitamin D levels.

As to whether taking a vitamin D supplement causally helps to prevent or treat COVID-19, many questions remain. Would it work in everyone? Or just those with low levels? (Essentially every citizen in Boston this time of year, I write, as the snow briskly continues to fall.) Or would it provide benefits only to those at high risk of severe disease? And if one recommends it for patients, friends, and family, what’s the right dose? And the best formulation?

Fortunately, my hospital colleague Dr. JoAnn Manson is leading one of the many studies evaluating vitamin D, both as COVID-19 prevention and treatment. She has extensive experience running large clinical trials, all done by mail/remotely, so if we’re going to get an answer, she’s the right person to do it.

My prediction? Odds are it won’t do anything. But I hope I’m wrong.

That’s why we do the studies!

And here’s the David Meltzer podcast stream, in case you want to stay on this page and look at our cute dog.

January 31st, 2021

Are We Expecting Too Much from Our COVID-19 Vaccines?

Photo by Wolfgang Hasselmann on Unsplash.

There are no absolutes in life. And nothing is perfect.

Tom Brady isn’t always in the Super Bowl (hard to believe). Serena Williams occasionally exits tennis tournaments in the early rounds. Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep sometimes appear in movies that are stinkers.

I’ve always thought that Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York fits horribly on Fifth Avenue, and looks like a toilet (not an original thought). Even the Beatles unfortunately released Revolution 9, an interminable abstract sound collage of musical “art” — my vote for their very worst “song”.

So why, then, are we expecting perfection from our COVID-19 vaccines? The vaccines developed in record time and our best chance at controlling the pandemic?

That’s what struck me late last week when we heard the results of two important COVID-19 vaccine studies, one from Novavax, the other from Johnson & Johnson.

Both vaccines worked, but there’s a distinct tone of disappointment in some of the news coverage.

In the Novavax trial, which used a two-shot protein-adjuvant strategy, the vaccine was 90% effective in the United Kingdom, but only 49% effective in South Africa, with most of the vaccine failures in South Africa the result of the B.1.351 variant.

Johnson & Johnson used an adenovirus 26 (Ad26) vector vaccine and one shot. It was only 72 percent effective in preventing COVID-19 in the United States and just 57 percent in South Africa.

(Italics mine, to make a point.)

With the 95% protection in the Pfizer and Moderna studies of mRNA vaccines, the headlines making unfavorable comparisons are understandable.

But there’s a lot to like about these results, even based on the limited information available in the press releases.

Both studies faced a more challenging COVID-19 transmission dynamic than Pfizer and Moderna — with a global surge in cases and emerging variants that are more contagious, potentially of greater disease-causing virulence, and harboring antigenic properties making them more evasive of vaccine protection. We simply don’t know how the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines would perform under similar pressures.

And both vaccines appear to prevent severe disease, a critically important endpoint. (Numbers are small in the Novavax press release, but still in the right direction.) Since it’s highly unlikely we’ll ever be able to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 from the planet, converting it from something that fills our hospitals into a nuisance respiratory virus — causing a mild cold or sore throat — is a welcome trade-off.

https://twitter.com/VirusesImmunity/status/1355149007220310019?s=20

Prevention of severe disease is something all of these vaccines appear good at, according to a summary by my Boston ID colleague Dr. Roby Bhattacharyya.

Or, as put quite succinctly by longtime vaccine expert Dr. Paul Offit:

You want to stay out of the hospital, and stay out of the morgue.

More good news — neither vaccine requires the kind of ultra-cold storage of the mRNA vaccines, a huge plus for distribution. And a one-dose strategy could greatly speed getting a larger number of people with at least some protection.

Meanwhile, in related news, reports of COVID-19 vaccine “failures” continue to make headlines, again making me wonder — why are our expectations so high? Did we really expect these vaccines to be perfect? We’re still in the middle of a pandemic, with only a small fraction of the population vaccinated.

Of course, cases of COVID-19 will continue to occur, even after vaccination. They are not 100% effective, even under the best-case scenario of a clinical trial. What we’re hoping for with vaccination is that there will be fewer cases, that they will be less severe, and hopefully less contagious.

I’m highlighting the distinction between “fewer/less” versus “zero” because there’s reason to expect that real-world effectiveness will not match clinical trial efficacy. We must guard against reports of vaccinated individuals who get COVID-19 as evidence that they don’t work at all.

We don’t know, for example, how they will perform in the frail elderly or the severely immunocompromised — people too infirm to participate in the clinical trials, yet appropriate targets for early immunization. Plus, the variants may make their effectiveness lower than in clinical trials, which is why sequencing of cases that occur after vaccination will be critical.

The true effect on disease incidence must await large, population-based studies — studies we’re likely to see relatively soon, such as these encouraging preliminary data from Israel, which so far has vaccinated a higher proportion of its population than any other country.

Meanwhile, let’s stop expecting perfection, carefully review the emerging research, and focus on getting as many people vaccinated as fast as possible.

And enjoy this amazing medley as a Revolution 9 palate cleanser.

January 24th, 2021

John Bartlett and Hank Aaron — Consistently Great for a Long, Long Time

Early last week, we lost one of the true giants in Infectious Diseases, Dr. John Bartlett. Long-time Chief of ID at Johns Hopkins, he was a true Infectious Diseases polymath — deeply knowledgeable about such a wide range of topics that virtually everyone in our field knew and respected him.

Early last week, we lost one of the true giants in Infectious Diseases, Dr. John Bartlett. Long-time Chief of ID at Johns Hopkins, he was a true Infectious Diseases polymath — deeply knowledgeable about such a wide range of topics that virtually everyone in our field knew and respected him.

If you’ll permit me to lift this from a previous tribute to John, here’s a partial list of his areas of expertise:

- HIV. Check.

- Clostridioides difficile. Check.

- Respiratory tract infections. Check.

- Antimicrobial resistance. Check.

- Anaerobic pulmonary infections. Check.

Given that breadth of knowledge, it’s no wonder that his annual summaries of “What’s Hot” in Infectious Diseases were must-see events at every IDSA/IDWeek meeting.

Year after year after year.

This consistency of greatness is no small feat. People get sidetracked. Or tired. Or motivated by greener pastures (money). Or hyper-focused on their own areas of expertise. As the famous quote goes, “An expert is one who knows more and more about less and less until he knows absolutely everything about nothing.”

John was the polar opposite of this kind of expert.

I’m convinced he maintained this broad view of our field because he was just such an innately curious and enthusiastic person. A (very) small example — I remember telling him of the surprisingly high treatment failure rates in people with high HIV viral loads with the two-drug combination of raltegravir and boosted darunavir in ACTG 5262.

“But they’re two of our best drugs,” he said to me in astonishment. (He was right about that.) “That’s absolutely fascinating! Why do you think that happened?”

For the record, we’re still not quite sure. But it did. And you can be sure that John was genuinely interested, immediately scribbling down a note about it on those ubiquitous yellow pads he carried with him everywhere.

Another remarkable quality of John’s was his extraordinary prescience, always knowing the next “big thing” in Infectious Diseases, often years before others. Here’s text from a paper he published — in 2008:

The United States needs to be better prepared for a large-scale medical catastrophe, be it a natural disaster, a bioterrorism act, or a pandemic. There are substantial planning efforts now devoted to responding to an influenza pandemic… Here, we identify some harsh realities: the US healthcare system is private, competitive, broke, and at capacity, so that any demand for surge cannot be met with existing economic resources, hospital beds, manpower, or supplies.

Chilling. Can you imagine how strong John’s voice would have been in our COVID-19 response had he been well enough this past year to participate?

John’s kindness and approachability, combined with his encyclopedic knowledge of all things ID, allowed him to teach, influence, and mentor countless medical students, residents, and fellows over the years. A distinguished chief of medicine (not an ID doctor) just told me she learned all her fundamental clinical ID knowledge from him during her residency at Hopkins. I have heard this same anecdote from numerous others.

Since everyone adored John, he used these relationships to gain insight from researchers and experts from all over the ID world. If someone started a clinical trial using a novel probiotic to prevent C. diff, he’d call that person and get the inside scoop (never disclosing non-public information, of course). Why this probiotic? What were the goals of the study? The challenges? What did they envision as the long-term risks and benefits?

“I wondered about why they chose this approach,” he’d say, “so I called Dr. — up, and here’s what he told me …” Hearing him talk about cutting edge ID clinical research was inside baseball at its best.

Speaking of baseball — this past week we also lost one of the greatest players who ever lived, Henry “Hank” Aaron, whose long and distinguished career strikes me as quite similar to John’s.

(Yes I can find baseball in anything.)

Aaron could hit for power, hit for average, throw, run, and field — a five-tool player, analogous to John Bartlett’s broad expertise. And it was sustained greatness, year after year after year. In baseball history, nobody was great for longer than Hank Aaron:

Nobody ever played the game so well, so consistently, so long. He was the wave crashing upon the shore.

That Aaron did this in the face of blistering racism, especially as he approached (and passed) Babe Ruth’s home run record, makes his achievements all the more impressive.

Two remarkable people — John Bartlett and Hank Aaron. What a week.

January 18th, 2021

COVID-19 Vaccine Frequently Asked Questions

In case you missed it, over on the New England Journal of Medicine, we now have a list of Covid-19 Frequently Asked Questions.

In case you missed it, over on the New England Journal of Medicine, we now have a list of Covid-19 Frequently Asked Questions.

(Why this NEJM Journal Watch site and the actual New England Journal of Medicine use different capitalization rules for this disease is a mystery. And don’t get me started on the Washington Post, which writes it as “covid-19”– all lower-case.)

It’s been a fun project to put these FAQs together, and my great hope is that it’s useful to clinicians and others who have questions about these amazing vaccines. Turns out I’ll learn a lot too.

So far, the single question that has drawn the most attention is this one:

Do the vaccines prevent transmission of the virus to others?

In my response, I try to highlight the fact that while we don’t have ironclad proof, it is highly likely that they will lower the risk. I urge you to read the full question where I outline the evidence so far.

In my response, however, I wrote this:

If there is an example of a vaccine in widespread clinical use that has this selective effect — prevents disease but not infection — I can’t think of one!

Some colleagues now have pointed out a few examples — diphtheria, meningitis B, and pertussis. My apologies for not mentioning these! We will update the site, and thanks for pointing this out.

Nonetheless, the general (if not ironclad) rule that vaccines typically reduce the risk of transmission to others remains true. After all, this is the primary reason why we have policies on mandatory school immunizations, influenza vaccines for hospital employees, and country-specific entry requirements for the yellow fever vaccine. Rubella immunization in particular is critical to prevent transmission of this otherwise benign infection to pregnant women. We also stress the importance of having immunizations up to date for people living with a person with a weakened immune system for this reason.

Sometimes it turns out to be an ancillary benefit of vaccine recommendations. This happened with expanded childhood immunization for pneumococcal disease, which has lowered the incidence in adults.Thanks, kids!

And it can be a great additional motivating factor for people considering the vaccine who might otherwise be undecided. Getting the shot protects you and protects others.

The challenge for us — as summarized in the New York Times — is communicating optimism about the vaccine’s high likelihood of reducing transmission, while at the same time acknowledging that we don’t yet know how much they’ll do so.

The overall message of the piece is that we’re “underselling” these vaccines. That the proven benefit of preventing severe disease is being undermined by caveats regarding disease transmission — about which we have limited, but promising, evidence.

(I suspect it will be a lot, though not 100% — but we’ll see.)

What to do practically in the meantime is also tricky, especially since the vaccine roll-out will be a process that takes months.

Here I totally agree with this piece’s well-stated conclusion, which I’ll quote in full.

We should immediately be more aggressive about mask-wearing and social distancing because of the new virus variants. We should vaccinate people as rapidly as possible — which will require approving other Covid vaccines when the data justifies it.

People who have received both of their vaccine shots, and have waited until they take effect, will be able to do things that unvaccinated people cannot — like having meals together and hugging their grandchildren. But until the pandemic is defeated, all Americans should wear masks in public, help unvaccinated people stay safe and contribute to a shared national project of saving every possible life.

Perfect! And looking forward to a time when the proportion of unvaccinated people is much smaller than it is today.

January 11th, 2021

After Ivermectin Controversy, A COVID-19-Free ID Link-o-Rama

Wow, quite the week for this country of ours. We’re all deeply saddened by the events, very hopeful that the transition in leadership will be peaceful.

And also an eventful week for this little blog. When I wrote “Enter ivermectin — and let the controversy begin,” little did I know.

Amazingly, this is already the second-most widely read post on this site over the past 365 days, and it’s been out less than a week. It’s closing in on number one, which came in early March — that’s when I not-so-boldly predicted we’d see a big increase in COVID-19 cases. Quite the visionary, wasn’t I?

(That was a rhetorical question.)

Anyway, who knew this obscure antiparasitic agent would capture so much attention?

With that controversy out of the way (ahem), allow me to return to non-COVID-19 ID/HIV for a brief time. I’ve been doing inpatient ID consults quite a bit recently, and here are a few of the interesting things that popped up:

- Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae is a nasty, nasty bug. In addition to liver abscesses, it frequently causes metastatic infection elsewhere, including septic arthritis, meningitis, and endophthalmitis.

- Nodular “granulomatous” pneumocystis pneumonia is an unusual radiographic presentation of PCP. Not all PCP presents with diffuse ground-glass infiltrates — and yes, I still abbreviate it PCP (PneumoCystis Pneumonia). Note that sputum induction and BAL may have lower sensitivity in granulomatous PCP, which will warrant other diagnostic strategies. For example …

- A markedly elevated beta-glucan in a person with HIV and respiratory symptoms is PCP until proven otherwise. Disseminated Talaromyces marneffei and histoplasmosis can also greatly increase beta-glucan in people with HIV, but PCP is way more common. (Should I change to saying PJP? It’s Pneumocystis Jirovecii Pneumonia, after all.)

- This is also true with non-HIV related immunosuppression, where a high beta-glucan and a compatible clinical syndrome are all but diagnostic. Many of the “false positive” beta-glucan results are not very high, or represent testing done in low pre-test probability settings. ID fellows will recognize that fact instantly! (Seems that switching to PJP is just a matter of time. Oh well. I’ll live.)

- Prior treatment failure of hepatitis B with lamivudine may induce entecavir cross-resistance. This is why it’s so critical that our heavily treatment-experienced patients with HIV/HBV receive tenofovir-based regimens — many received lamivudine for years before we knew about this issue of HBV cross-resistance.

- The preferred treatment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is TMP/SMX. Optimal dosing is unclear, though our crack ID pharmacy team recommend 12 mg/kg/day of the TMP component. (12? Not 10 or 15?) And yes, this is one of those fabulous ID tongue-twister bugs — one of the more common ones.

- TMP/SMX is probably as effective as pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine for CNS toxoplasmosis. Certainly it’s way less expensive (pyrimethamine, ouch), and much easier to take. It’s already standard of care in most of the rest of the world. Will our HIV opportunistic infection guidelines make this the case here in the USA as well? At least list it side-by-side with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, rather than listing it as an alternative?

- Intramedullary spinal cord abscess is a rare CNS infection that may be complicated by spinal artery occlusion. This review notes that 40% are cryptogenic, 20% come from a dermal sinus, and 20% from bacteremia. High incidence of permanent neurologic sequelae.

- Hair loss is a well-recognized complication of prolonged fluconazole use. Anecdotally I’ve seen this most commonly in those being treated for candida endocarditis, cryptococcal meningitis, and osteomyelitis. I’m sure it’s true for coccidioides, too, but we don’t see much of that in Boston. It slowly improves after stopping therapy, or decreasing the dose. In a similar theme …

- Blue skin is a well-recognized complication of prolonged minocycline use. Most cases do resolve over time after cessation of the drug, but sometimes it can be permanent. And it’s not just the skin — here’s a blue aorta!

- While UTIs in older adults no doubt are overdiagnosed (and overtreated), this paper hints that undertreatment may be a problem too. The problem is that assessing whether positive urine cultures are symptomatic — especially in older adults with cognitive impairment and multiple comorbidities — is an enormous challenge.

- Oral beta-lactam antibiotics might be a reasonable option for treating gram-negative bacteremia after all. The dogma has always been to use a fluoroquinolone or TMP/SMX. This study suggests beta-lactams may be a good option, provided it’s a urinary source and that initial treatment is parenteral.

- Penicillin-susceptible Staph aureus can be treated with penicillin — provided the microbiology laboratory confirms it’s truly sensitive. The critical thing is that the lab does this testing — some don’t. Anecdotally, penicillin is better tolerated than nafcillin and oxacillin, too.

- Should osteomyelitis complicating sacral pressure ulcers be treated with antibiotics? Generally no, argues this persuasive paper. And this question comes up all the time on inpatient ID services.

- Certain clinical and laboratory features are predictive of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) due to M. avium complex (MAC) in people with HIV. This contemporary series cites low body mass, low hemoglobin, and elevated alkaline phosphatase as readily available predictors. Note that the literature on management of HIV-related MAC IRIS is badly out of date. When should steroids be started? How long should they be continued? What are the side effects? A good project for a large cohort study.

Many thanks to ID fellows Drs. Susan Stanley, Alex Tatara, and Zach Nussbaum for providing some of these references. And remember all you fellows out there, you’re more than halfway done with your first year of fellowship!

For next week? Maybe I’ll write about albendazole. Or praziquantel. Or nitazoxanide. Or some other antiparasitic agent. They seem to be quite popular!

Or maybe I’ll just watch this baby bear playing on this golf green.

January 4th, 2021

Ivermectin for COVID-19 — Breakthrough Treatment or Hydroxychloroquine Redux?

It’s an indisputable fact that we need better treatments for COVID-19.

This is particularly true in the outpatient setting. Let’s count how many we have today, hmm, this shouldn’t take long. That would be zero — the same number we had over a year ago, when the disease first emerged in China.

Something safe, easy to take as a pill, and inexpensive. Something that isn’t a costly bioengineered molecule that requires lengthy infusions, given within a short time after diagnosis, to a highly contagious person.

Enter ivermectin — and let the controversy begin.

Yes, ivermectin — the drug licensed for use against strongyloides and other parasites, and probably best known to primary providers for its off-label use for scabies and head lice, and for pet owners as a common de-worming agent.

Of course upon hearing about this “repurposed” antiparasitic drug, many will develop a weary feeling of deja vu.

Didn’t we make this mistake with hydroxychloroquine? Wasn’t excess enthusiasm for this treatment a dismal chapter in our clinical and research approach to this new disease? Enthusiasm that led to wasteful, duplicative clinical trials, flawed observational studies, and irrational prescribing with arguably more harm than benefit? Harms that included not just side effects, but also drug shortages and pointless stockpiling?

Yes to all of the above.

Note that the harm done by the hydroxychloroquine controversy continues to this day. I know investigators who led well-done, fully powered clinical trials with negative results who were, and continue to be, viciously attacked in emails and on social media. Accusations typically charge that they succumbed to pressure from big pharma, or obscured favorable study results based on political agendas, or both.

Believe me, they wanted hydroxychloroquine to work. We all did! It’s relatively safe, inexpensive, widely available — but oh well, the clinical trials showed us it didn’t do much of anything.

Now — back to ivermectin. Where do we stand today? Unlike in the spring, when hydroxychloroquine use was rampant pretty much everywhere (and even appeared in some institutions’ treatment guidelines), this poll suggests that ivermectin use now is much more restrained:

Hey #IDTwitter and other clinicians who care for people with #COVID19. Have you prescribed (or recommended) ivermectin for this disease? Please vote and comment. Thank you!

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) January 3, 2021

However, there is a strong likelihood that the group voting on this little poll does not represent clinical practice globally. An article in October cited widespread use throughout Latin America, and many commenters to the above poll mentioned similar practices in their countries. Here’s a group of mostly South and Central American clinicians strongly advocating for ivermectin therapy for COVID-19.

Furthermore, many push for broader use of ivermectin in the U.S. as well. A group called the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance — made up of predominantly critical care clinicians — devotes much of its organization’s homepage to ivermectin’s promise for COVID-19 treatment, which they summarize in enthusiastic detail here.

Beyond these accounts, what else is out there?

The best summary of the research evidence to date appeared recently in a presentation by Dr. Andrew Hill from the University of Liverpool. In a conference hosted by MedinCell, a company developing a long-acting ivermectin preparation, he presented the interim results of a meta-analysis funded by Unitaid.

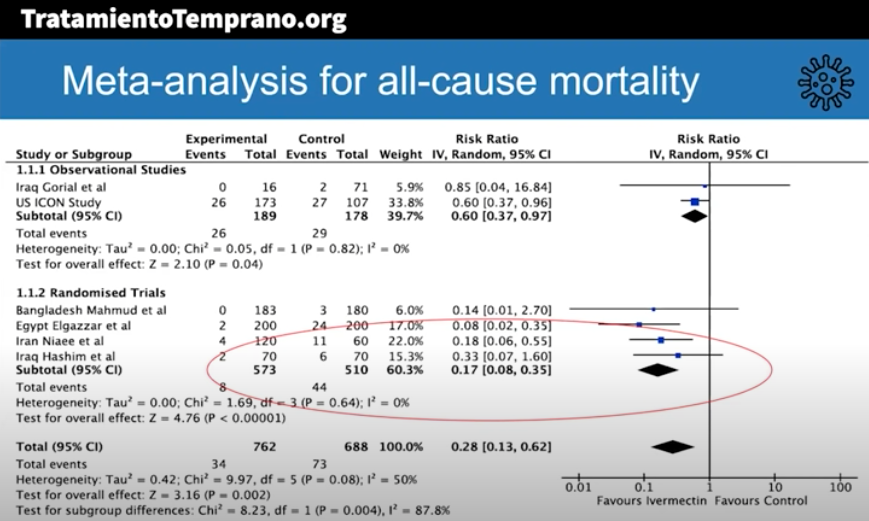

Here are some key results (posted with permission):

The risk-ratio for mortality with ivermectin was 0.17 (95% confidence interval 0.08, 0.35), an 83% reduction in risk of dying. Outcomes for other endpoints (time to viral clearance, time to clinical recovery, duration of hospitalization) also favored treatment over controls.

Andrew was kind enough to speak with me today, mentioning that additional clinical trials will be included in the final meta-analysis, and that results are confirmatory. Some studies also included inflammatory markers such as D-dimer and IL-6, with favorable outcomes seen in these endpoints as well.

The presentation appropriately cites the limitations of the meta-analysis, which include the incompleteness of the data, that some of the studies were open label, and the difference in dosing regimens and endpoints. Also — critically important — publication bias may play a role, where we’re only privy to the studies that have what he calls the “good news.”

To further muddy the waters, “publication bias” is a generous term — none of these trials have yet been published in peer-reviewed journals.

Doubters will also understandably cite the very unimpressive pharmacokinetic (PK) data on ivermectin’s antiviral activity. Here’s our ID PharmD Jeff Pearson’s take:

I hope I’m wrong, but I don’t believe ivermectin will work for the treatment of COVID-19 for a variety of reasons (mostly being its PK, see here, here, and here).

But of course PK studies don’t always correlate with clinical activity, and ivermectin may have anti-inflammatory activity, as shown in this animal model.

My take-home view? The clinical trials data for ivermectin look stronger than they ever did for hydroxychloroquine, but we’re not quite yet at the “practice changing” level. Results from at least 5 randomized clinical trials are expected soon that might further inform the decision. NIH treatment guidelines still recommend against use of ivermectin for treatment of COVID-19, a recommendation I support pending further data — we shouldn’t have to wait long.

But we have to guard against two important biases here. First, that because we were burned by hydroxychloroquine means that all other repurposed antiparasitic drugs will fail too.

Second, that studies done in low- and middle-income countries must be discounted because, well, they weren’t done in the right places.

That’s not just bias, it’s also snobbery.

December 20th, 2020

With Vaccine Rollout, a Mixture of Gratitude, Envy, and Cautious Hope

Did I think we’d have two vaccines for COVID-19 available for distribution before 2021? Two vaccines with 95% efficacy in preventing disease, and nearly 100% in preventing severe disease? Vaccines that work across different patient populations, including the most vulnerable — especially older people?

Not a chance. I’ve probably been quoted half a dozen times saying that we likely wouldn’t be seeing vaccines before next year. Some “expert,” ha.

And yet, here we are. In this interview yesterday, you can clearly hear the excitement in my voice as I discuss the second emergency use authorization for the Moderna vaccine. Giddy.

Yes, it’s time to celebrate, to shed tears of joy when receiving the vaccine, to display happily the image of a bare biceps and the injection taking place, both vaccinator and vaccinated clearly smiling beneath the masks.

It’s even time to dance!

https://twitter.com/JournalsDance/status/1339875341628821506?s=20

II. Envy

Several friends and family members have asked — have you received your COVID-19 vaccine?

Answer: Not yet.

Can’t blame them for asking — I’m an ID doctor, after all, and finished a rotation of inpatient service just before Thanksgiving, and am about to start another over the the Christmas holidays. Most of us have been working solidly since March, no encampment to our country estates.

They might also ask after my wife, a primary care pediatrician who sees sniffly and coughing kids every day in her office practice, kids accompanied by their parents — many of them young adults at high risk for community acquisition of COVID-19.

Not yet for her, either.

The harsh reality is that there’s not yet enough vaccine to go around. Not even close.

In my hospital system, the overwhelming volume to sign-up for “Wave 1” of vaccine administration (of which I’m a part), initially caused the process to crash. It then reopened for approximately 15 minutes before the schedule filled. The supply is limited due to distribution issues beyond the hospital’s control.

Some did successfully sign up, but the first-come, first-served nature of the process allowed people to time their participation — you can be sure many set their phone alarms to go off at the precise moment the schedule came online again. Perhaps this process excluded those working the hardest, with the irony of this disconnect not lost on some.

But problems notwithstanding, I (and others in this first wave) likely will get the vaccine soon — I’m optimistic since with this second vaccine’s authorization, our hospital system’s supply should increase quickly.

My wife can’t be so certain. She and her partners own their practice, and their primary hospital does not have enough vaccines for affiliated primary care pediatricians or their staff.

Meanwhile, thousands of doctors (including several of our friends), nurses, respiratory therapists, and other frontline workers around the country have been vaccinated. Hooray! Plus, notably, some politicians blue and red — even Santa Claus.

Good for them. We’re happy for them.

But we’re envious, too. And if we feel this way, imagine how the broader public feels — those sequestered away the last 9 months, tired of the isolation, many older and at risk for severe COVID-19 and terrified. No accurate timeline for their vaccines. No wonder people are trying to jump the queue.

And yes, it’s hard to see those vaccine selfies, ouch.

https://twitter.com/DrSandman11/status/1339565524213182464?s=20

III. Cautious Hope

Hard to be hopeful right now. Cases continue to increase across the United States — now well more than 200,000 a day, with our country’s cumulative death toll over 300,000.

And unlike earlier surges, which targeted different regions at different times, this time it’s everywhere.

For the first time.

All red USA, now including Hawaii, for out of control covid.https://t.co/BpmBybV8U5 pic.twitter.com/Zyt8Uiaeq8— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) December 16, 2020

Public policies may be different from earlier surges — no extreme shutdowns — but that doesn’t mean things are safe, which is why so many caution against large holiday gatherings.

With these discouraging facts before us, how can we have any hope?

First, we have these two amazing vaccines cited above. An additional promising candidate — the Johnson & Johnson vaccine — has completed enrollment, with results expected in January. That vaccine requires only one dose and has way less stringent cold storage requirements. The AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine is on a similar timeline for availability, provided there are no further safety or efficacy setbacks.

Second, after months of logjams, rapid home testing for COVID-19 quietly advances. Two such tests have recently garnered approval — the Ellume and the BinaxNOW; others are in the works, and I increasingly hear people broadly supporting “flooding the market” with these tests. Here’s a letter sent to Congress summarizing why we need them, and how to get them approved and supported.

Because if people are going to get together — and they will — some testing is better than no testing, and lots of frequent testing is better yet.

Could we envision socializing safely with friends and family by the early spring, all of us recently vaccinated, and having a negative home test as a safeguard? And schools opening in the fall in ways that seem somewhat normal? Absolutely.

Third, starting early this week, the days start getting longer.

See, was that so hard?

December 13th, 2020

Brush with Greatness — Rochelle Walensky to Head CDC

There’s an overused expression that, despite its familiarity, really does describe some people perfectly. It’s when you say someone “lights up a room.”

My ID colleague and friend Dr. Rochelle Walensky certainly stands as a prime example. Right from the moment we first met during her interviews for ID fellowship in the late 1990s, I noticed Rochelle gave off this remarkable positive energy — a mix of enthusiasm, intelligence, and attentiveness that’s immediately obvious to all.

Here’s someone special, one inevitably thinks when meeting her. Here’s someone who listens and can get things done.

Of course, I write this soon after she’s been named the next head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a position she takes after 3 distinguished years as Chief of ID at Massachusetts General Hospital.

And while this move came as a surprise even to those who work closely with her — well played, Rochelle! — once the announcement became public, the response from the ID community has been nothing short of celebratory. I’m far from alone in holding this high opinion of her.

What can we expect from our new CDC director? If the track record from her work to date is any indication, let’s look forward to the following:

- Skillful analysis of data. She’s a highly accomplished researcher in disease modeling, having published nearly 300 papers, many quite influential, along with more in the popular press. And she loves numbers. CDC generates lots of numbers. She’ll most definitely fight COVID-19 with “science and facts.”

- Effective communication. A particular strength is her ability to convey complex information in a way that is understandable to people outside her field. Disease models may seem like the quintessential “black box” of computer spreadsheets and databases, but in Rochelle’s words, they are logical and clear.

- Generous leadership. A winner of several mentorship awards at Harvard, she will credit her team for their accomplishments. Don’t be surprised if we’re re-introduced to some spectacular talent at CDC — which will once again have a prominent voice. Welcome back!

- A focus on equity. Her colleague Dr. Robert Goldstein summed it up perfectly: “She approaches every part of her work understanding that, to do this well, we have to think about those that are most vulnerable and those that are most marginalized in our system.”

- A great doctor and a compassionate human being. When she was a first-year ID fellow, she was concerned about a young man from Africa who had been admitted with malaria and discharged home. Now, first-year ID fellows are incredibly busy; nonetheless, she took extra time in her clinic to see him in follow-up until he recovered.

Allow me to linger for a moment on this last one, the compassion piece. Rochelle made the extra effort to ensure her patient — new to this country, feverish from malaria, afraid — had good care. This is what good doctors, and good human beings, instinctively do. I have no doubt that had she chosen clinical care over research as her primary focus, she would have excelled in this domain as well.

And isn’t that human touch still so glaringly absent from our national response to the pandemic? Where’s the compassion? The appreciation for the sadness and sacrifice?

Rest assured, with Rochelle heading the CDC, that will soon be clearly evident, as she’s joining a distinguished group on the COVID-19 response known for their talent, character, and achievements.

Now, skeptics could read this post, and think, come on — nobody is this great. There must be something Dr. Rochelle Walensky doesn’t do well.

Ok, here it is.

She has lousy handwriting.

Nobody’s perfect.