An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 19th, 2011

Going, Going, Gone … HIV Treatment Failure Is Disappearing in People Who Take Their Meds

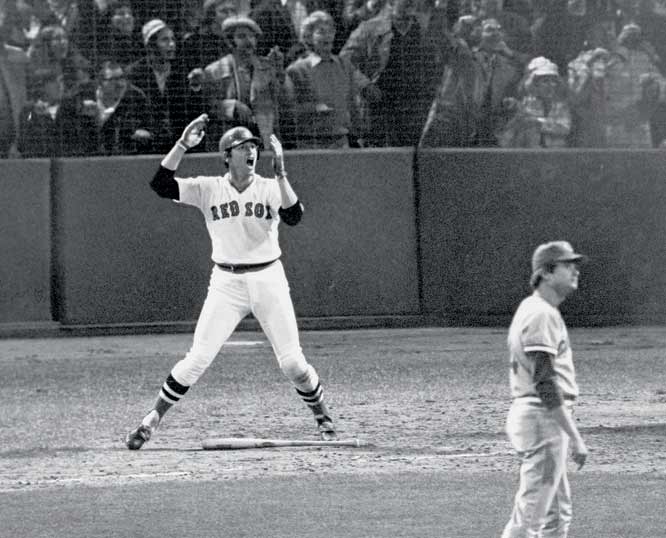

World Series time, hence the baseball reference in the title.

World Series time, hence the baseball reference in the title.

(Doesn’t take much.)

But over in Lancet Infectious Diseases — which has turned out to be a terrific journal, by the way — there’s a study reminding us that advances in HIV treatment in the late 2000s were truly spectacular.

The goal of the paper was to track the outcome of patients with “triple-class virologic failure” (TCVF) over the course of the last decade. Using data from 24 European cohorts, the investigators had access to over 90,000 patients, out of whom 2722 failed treatment with regimens that at some point contained the original three drug classes: NRTIs, PIs, and NNRTIs.

Rates of virologic suppression after TCVF steadily increased over the decade, from 19.5% in 2000 to 57.9% in 2009, and both AIDS complications and deaths declined. Significant predictors of virologic suppression by multivariable analysis included later calendar year, transmission category (MSM did the best), low viral load, and high CD4.

Those who had previously been able to achieve virologic suppression before TCVF were also more likely to be successfully treated — this clearly being a marker for good adherence. And although “past performance is no guarantee of future results,” it sure can be useful regardless. You have to assume that most of the 40% or so who did not achieve virologic suppression simply didn’t take their meds.

So what’s missing from their analysis?

Notably, because our objective was mainly descriptive, we did not attempt to further adjust for time-dependent variables such as access to new drugs …

In other words, the single most important factor for improved treatment outcomes in the 2000s — the introduction of darunavir, raltegravir, maraviroc, and etravirine — is left out.

(They also didn’t include data on resistance or adherence, but I suspect the former was tough to find, and the latter probably didn’t change all that much.)

So these results are either truly remarkable (if you follow HIV from a distance) or, if you are actively practicing HIV medicine day-to-day, are so obvious you can legitimately wonder why they did the study in the first place.

Both reactions are appropriate.

Categories: Health Care, HIV, Infectious Diseases, Patient Care, Research

Tags: antiretroviral therapy, HIV

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

One Response to “Going, Going, Gone … HIV Treatment Failure Is Disappearing in People Who Take Their Meds”

Paul E. Sax, MD

Contributing Editor

NEJM Journal Watch

Infectious Diseases

Biography | Disclosures | Summaries

Learn more about HIV and ID Observations.

Search this Blog

Follow HIV and ID Observations Posts via Email

Archives

-

-

From the Blog — Most Recent Articles

- When AI Gets the Medical Advice Wrong — and Right November 18, 2025

- Hot Takes from IDWeek: CDC, COVID, and Two Doses of Dalbavancin November 13, 2025

- Favorite ID Fellow Consults: Johns Hopkins Edition November 7, 2025

- Two Covid Vaccine Studies — One Actionable, the Other Not So Much October 28, 2025

- What a Difference a Year Makes — with Bonus Halloween Video October 23, 2025

NEJM Journal Watch — Recent Infectious Disease Articles

NEJM Journal Watch — Recent Infectious Disease Articles- Botulism Cases in Babies Have Been Linked to Infant Formula

- What's the Effect of Delayed Surgery for Septic Arthritis?

- Community-Acquired Meningitis: Watch Out for Klebsiella

- Observations from ID and Beyond: Hot Takes from IDWeek: CDC, COVID, and Two Doses of Dalbavancin

- Frailty Predicts Outcomes in Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Bacteremia

-

Tag Cloud

- Abacavir AIDS antibiotics antiretroviral therapy ART atazanavir baseball Brush with Greatness CDC C diff COVID-19 CROI darunavir dolutegravir elvitegravir etravirine FDA HCV hepatitis C HIV HIV cure HIV testing ID fellowship ID Learning Unit Infectious Diseases influenza Link-o-Rama lyme disease medical education MRSA PEP PrEP prevention primary care raltegravir Really Rapid Review resistance Retrovirus Conference rilpivirine sofosbuvir TDF/FTC tenofovir Thanksgiving vaccines zoster

So, they ignore the most obvious and likely largest confounder? Your reaction and mine are similar.