An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

September 8th, 2023

Endless Recertification in Medicine — Some Thoughts About the Tests We Take

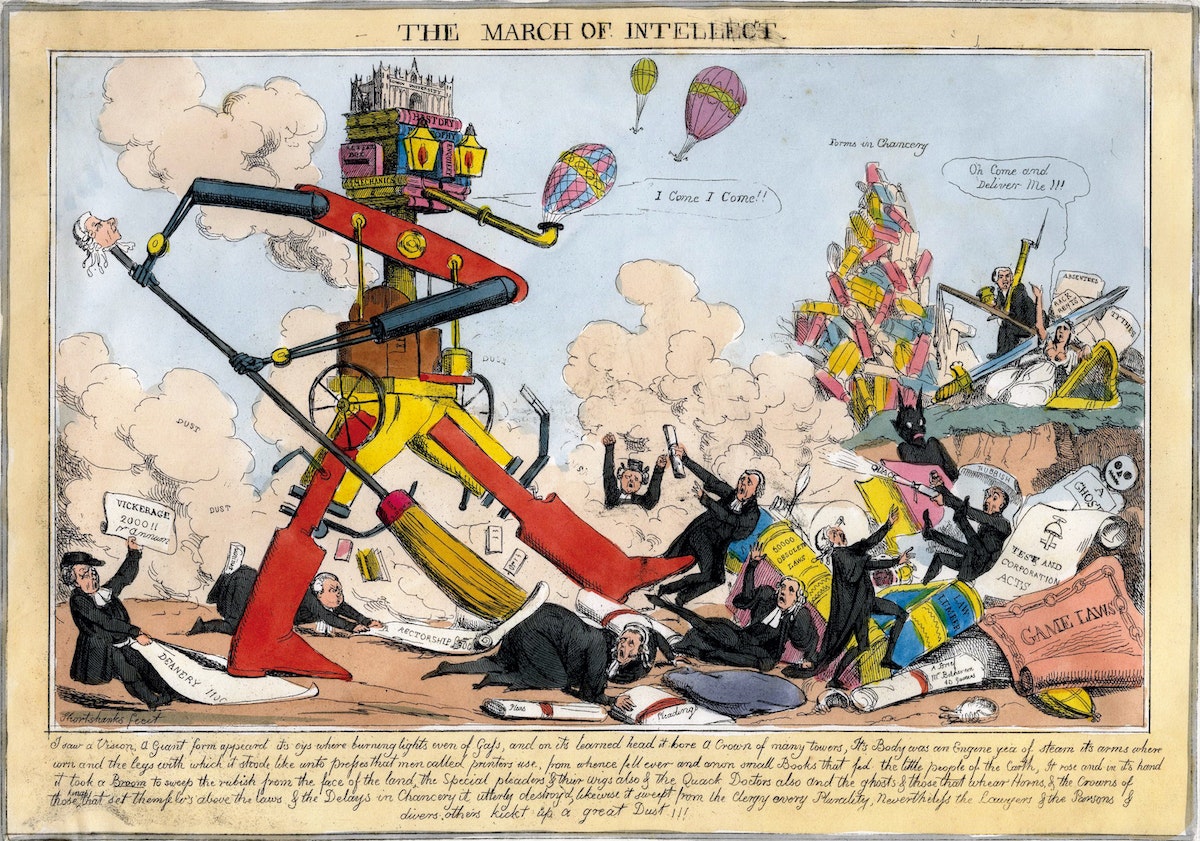

William Heath, March of Intellect, 1829.

The tests issued by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) for credentialing physicians are much in the news again. There’s even a petition circulating to eliminate the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) process entirely, signed by nearly 20,000 physicians.

I have a bunch of memories, thoughts, and feelings about ABIM and the tests they issue. They’re all jumbled around in my head in a formless blob.

So formless, in fact, that I struggled to put them into a well-structured post. So here they are, in 6 chapters, presented in roughly chronological order.

Chapter 1: The Early Days

I remember a meeting we had during my medical residency where someone from ABIM came to our program to announce the end of “lifetime certification,” starting with our year of residency. (I think he was from ABIM … it was a person not on our faculty.) We were the very first year with a new requirement, thank you very much.

No longer would people who passed their Internal Medicine or subspecialty boards be “grandfathered in” for eternity. At 10-year intervals, repeat examinations would be necessary — length, type, cost to be determined.

(Origin of the term “grandfathered” — in case you were wondering.)

The new program was called “Maintenance of Certification,” or MOC, and would provide hospitals and insurance companies a different benchmark for credentialing physicians. You signed up for MOC by sending in a sizable payment, and then the ABIM site would list you as participating in the program. ABIM promised to send you reminders when your 10-year period was about to expire.

As we heard it, it was a decision passed down from above, one with authority that we assumed had strong data behind the policy. We had no way of pushing back or protesting.

No one opposed some sort of process of continual learning for physicians — but wasn’t that the purpose of good Continuing Medical Education (CME)? And it seemed especially ironic that only the older docs got a lifetime pass. We were miffed, but powerless.

The MOC process was widely adopted, and it became a standard part of employer checklists for hiring and retaining medical staff, and insurance companies for keeping or dropping you from their ranks. If Dr. Hugo Z. Hackenbush only passed his original exam, but failed to sign up for the repeat exams, he risked losing his job. Or not getting paid.

Quite the motivation to participate!

Chapter 2: The Middle Years — Criticism, More Requirements, and a Retrenchment

Widespread adoption notwithstanding, the ABIM and its requirements have long had their share of critics. A Newsweek article in 2015 was particularly vicious. More recently, cardiologist Dr. Westby Fisher has tirelessly laid out his arguments for elimination of the MOC requirement (arguments here and here).

Numerous other editorials and position papers have appeared over the years, too numerous to cite, with the message that ABIM has no good data that their process improves physician quality; that the tests are not clinically relevant; that it’s too expensive; that all it does is enrich an already financially thriving not-for-profit organization; and that it fuels clinician burnout.

The apotheosis of these criticisms came when ABIM added layers of other requirements to the MOC process beyond the recertification exams. Remember these “Practice Assessment, Patient Voice and Patient Safety” programs? Yeesh.

We all spent hours completing “quality improvement” projects of dubious (and sometime frankly bogus) worth, just to say we’d done it. Where did all these forms go once we submitted them? Was quality ever improved by these tasks? (Doubtful.) Who reviewed them?

As for “Practice Assessment,” I memorably asked a colleague of mine, a terrific clinical pulmonologist, to complete one of the ABIM mandated surveys on my behalf. He was supposed to call a toll-free number and answer a series of templated questions about the quality of care he’d observed me give to our mutual patients. He kindly agreed to do it.

Or so I thought — he later told me he never got around to it. But ABIM still said I passed his individual “Practice Assessment” standard. Maybe he sent them his response by telepathy?

Under a torrent of criticism, these extra requirements ended in 2015 with a mea culpa from the ABIM leadership. Good move on their part, as it was the very essence of overreaching by a powerful organization. But the recertification process (MOC) remains, as do the criticisms.

In short, complaining about ABIM, and the MOC in particular, offers a rare example of doctors coming together in a remarkable cross-specialty consensus. Accurate quote from Dr. John Mandrolla:

[ABIM] has done what seemed impossible: got docs of all political leanings to agree on one thing —> ending MOC.

Chapter 3: Taking the ABIM Exams

Through volume alone, I’m something of an expert on taking ABIM exams. I have ID specialty training along with Internal Medicine certification, so I’ve now taken the Internal Medicine boards 3 times, and the Infectious Diseases boards 4 times. Lucky 7!

I’ve spent thousands of dollars for the examinations, sitting for a whole day (a work day) in a high-security environment that treats all us test-takers like potential drug smugglers or terrorists. You check in at a test center, surrender all your possessions and place them in high school-style lockers, take the locker key with you, and head to the testing rooms.

These rooms are gloomy, windowless, and airless places, watched over by suspicious test proctors behind one-way mirrors. The rooms are filled with side-by-side desk cubicles. Each desk has a monitor, keyboard, and mouse.

(Computer mouse, not the squeaky rodent with whiskers. All living things would leave this hostile environment as fast as possible, and that includes vermin.)

The testing day has tight restrictions on bathroom breaks and lunch. You can’t ask anyone for help with anything related to test content. (What happened to medicine as a “team sport”?) You have one source of information — UpToDate. You keep feeling as if you’re about to infringe on some unspoken security policy, and end up being reported to the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), putting you immediately on a “no fly” list.

And here’s another thing about those thousands of dollars we pay for the privilege of taking the test — when you finish residency, nobody tells you who’s responsible for the payments. While some have it as a job benefit, most doctors must pay out of pocket, with time away from productive patient care — leading to additional lost revenue for those in private practice or paid by clinical RVUs. If you take a board review course, that’s an additional hefty sum.

In summary, taking the test is no one’s idea of a fun day at work, and the cost of ABIM MOC isn’t trivial — these rankle pretty much everyone I know.

Chapter 4: A View from Inside (Sort Of)

Full disclosure time — for several years, I was on the committee that wrote the questions for the ID boards.

(Ducks.)

I’d meet with ID colleagues twice yearly with diverse areas of expertise, and we’d test our questions against each other with the guidance of an ABIM official. These were incredibly educational meetings, and I learned a ton from my smart colleagues — arguably more than I’d learned preparing for or taking the boards themselves.

We tried to make the test questions as clinically relevant as possible, of course. Part of our job was to weed out those we thought tested pure memorization, or “look ups,” or highlighted outdated diagnostics or therapies. Each question was carefully reviewed so that there was a clear question, and an unambiguous single-best correct answer, at least so we thought.

But — and this is really important — no matter how good the question, we had no idea whether these test questions evaluated the clinical competency of a physician. This was always a big reach.

Two major barriers: First, not everyone in ID has the same spectrum of practice. Even within our little specialty, there are some who focus on transplant ID, and others who rarely if ever see these patients; some do lots of longitudinal HIV care, and others do none; some are deeply involved in infection control, while others barely touch the topic. I could go on and on, but these differences were obvious barriers to writing clinically relevant questions with broad applicability.

And I am 100% sure this issue applies to every medical specialty. Example — Dr. Mikkael Sekeres, who specializes in hematologic malignancies, describes what it’s like taking the MOC exam in Hematology-Oncology:

… over 90% of the questions have nothing to do with the patients I actually see in my specialty practice, and haven’t seen in over 2 decades of practice.

The second problem was the test process itself. To be blunt, nobody practices medicine in the style of the proctored exam — high stress, limited information resources, time-limited, non-collaborative. No testing of the importance of patient communication, eliciting preferences in ambiguous situations, accounting for differences in medical literacy, or the ability to seek out help from other clinicians. In a world of increasingly sophisticated emulations, the ABIM monitored test setting is the polar opposite of practice, and multiple choice question are an overly simplified probe of the complexities of clinical reasoning.

So what is being tested, really, with the ABIM exams? I learned that they’re evaluating the ability of candidates to answer test questions vetted by psychometricians as being “discriminating” — answered correctly by high-performing candidates and incorrectly by low-performing test-takers. These are the best questions, per ABIM standards.

It’s a form of circular reasoning that somehow is supposed to correlate with the ability to care for patients seen in the office or hospital setting. In other words, even our best, most clinically relevant questions sometimes got tossed out as being not discriminating enough — too easy or too hard based on this self-reflecting metric.

If you’re shaking your head right now, I don’t blame you.

Chapter 5: The Latest Innovation — Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment

Astute readers will note that I’ve “only” taken the Internal Medicine boards 3 times. It’s not because I’ve let that certification lapse — it’s because ABIM now offers a new way to maintain board status, and that’s by taking unproctored exams at home, called the “Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment,” or LKA.

Send in your payment, and 30 questions arrive quarterly, giving brief clinical vignettes, a question, and then multiple choice answers. Notably absent from the answer choices is “I would never manage a case like this on my own, I’d ask or refer to a colleague.”

Tough luck. You have 4 minutes to answer each one, and can use any resource.

Whether this LKA process more accurately correlates with clinical competency than the proctored high-security test is anyone’s guess. Four minutes to answer a clinical question? How did they come up with that? Does research show that 4 minutes is some magical threshold that skilled physicians find sufficient for every clinical question? Do the doctors needing 5 minutes need some sort of remedial training in how to look things up more efficiently?

Plus, I have no idea what the criteria are for success in this home testing program. I’m just answering the questions, hoping I’m getting enough questions right to maintain my certification status. La de da.

Certainly this LKA feels less punitive than the proctored exam at the dreaded test center. But there’s a negative trade-off, and it’s not trivial. These questions arrive on a regular basis, an endless 3-month cycle that stretches on indefinitely. It feels like a coach told you to start running laps for fitness but declined to tell you how many.

Big picture — do I really need to do this the rest of my career? I’m only a year or so into it, and confess it feels about as rewarding as renewing your car’s registration or paying your monthly utility bills.

And let the record show that the much-hyped flexibility of the LKA led to one of the most tone-deaf examples of organizational publicity in the history of academic medicine — a doctor posted, on the ABIM site, an account of her doing exam questions while “on the adventure of a lifetime, visiting all the lower 48 States in an RV.”

I’m sure she meant well. But the response from the medical community at the implication that we spend our vacation time doing MOC was predictable outrage.

Never forget!

Your MOC fees paid someone at ABIM to come up with this ad!END MOC sign the petitionhttps://t.co/OYfhsxZkkG pic.twitter.com/MzPI9Ct9Lv

— Aaron Goodman – “Papa Heme” (@AaronGoodman33) August 2, 2023

And while ABIM deleted the original tweet promoting the post (but not the post itself), and apologized for it, some of the responses were very, very funny indeed. Here’s my favorite:

Getting married this weekend and want to get a head start on Q3 LKA questions? Hear from Dr. Gunner, who completed her LKA questions between her wedding ceremony and reception!@ABIMcert pic.twitter.com/VZz18KNQl2

— Ari Elman, MD (@AriObanMD) July 30, 2023

Chapter 6: Looking back, Looking Forward

One of the very best decisions I ever made during college was to spend time doing something else before starting medical school. That one year — spent at a school in England, mostly teaching American literature to kids age 12-18 — was so rich with experience and challenges at my then tender age that it has greatly rewarded me many times over in the coming decades of my life.

Haven’t regretted it for a moment — even though it delayed medical training by 1 year, and hence meant missing out on being grandfathered in on lifetime certification in Internal Medicine. Oh well.

But despite my not regretting this 1-year delay, I can’t help wondering if the ABIM MOC is really the best way to make sure that doctors stay up to date. Couldn’t we do something less onerous? Less expensive? Something tied more closely to the actual clinical practice we do every day, adapted for each person’s particular patient profile? Something linked to existing CME requirements and state licensing? A competing credentialing process, the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS), started in 2015, and has gained some traction. Certainly it has its strong supporters.

In summary, it really does seem like it’s time for a change.

What do you think?

Having taken 3 Board exams and one Longitudinal exam and have been equally traumatized by all of them, I have vowed to retire before I ever have to take another! I agree wholeheartedly with eliminating this expensive, miserable way to measure clinical competency.

( Disclaimer, the Family Practice Longitudinal exam allows 5 minutes per question, a real luxury!)

A good argument against MOC is us grandfathers successfully practicing our specialties and subspecialties. I get my cme non MOC, as getting MOC credit costs $$$ that I don’t need.

I’d enjoy an easy online system that helps me keep current while assuring credentialing folks that my skills aren’t atrophying. LKA is a step in that direction.

That said, the MOC business model is predicated on requiring physicians to pay a whole bunch of money for … something… and then maybe later they figure out what works. It’s a perfect recipe for waste.

The same economic model drives net-harmful medical interventions being targeted by the ABIM’s Choosing Wisely campaign. It’s time to look within…

This. Is. Awesome. Why do we take it? Physicians unite!

Like you, I worked on the ABIM committee that wrote ID board questions. It was one of the best gigs I’ve ever had: fun, interesting, and highly educational. In fact, I probably learned more ID on that committee than I have anywhere else except fellowship, and certainly more than I learned by studying for or taking the boards.

I suggest we just put everyone on an exam-writing committee to create an exam that no one will take.

That’s a great idea. I am all for it. I am sure I can write a few questions.

Terrifically written and totally agree! Vetted, non-punitive CME is the way to go. LKA is a step in the right direction but still has its problems. Paul, get our colleagues at the IDSA on the same page and make a united stand against MOC!

EXCELLENT ARTICLE. Elected LKA for my third recertification. Sure, I can answer the questions, but it’s a means to what end?? After nearly 25 years in practice I know how find answers to my frequent questions that pertain to optimal patient care-it’s called professional competency. MOC isn’t going to help with that or make me a better doctor(unlikely to help most of us). This outdated model seems predicated on the assumption that you’ve not read a thing and only through MOC can you stay competent and up to date. Seriously, does any other profession do this to their members? It’s just another insult to our integrity.

I transitioned to the LKA for my 2 subspecialties but have continued the 10 yr exam for my IM. I don’t think our board certification should be tied to MOC, the lifetime model was the correct model for certification along with ongoing CME required by our state medical boards and employers. I will say that I have found the LKA to be a good learning model and would likely be willing to continue to pay for and use it as a form of CME (I enjoy the immediate feedback of seeing the correct answer and the discussion of why it was the correct answer).

I don’t think we should continue to be forced to pay the ABIM to prove our competency and I don’t think it really has anything to do with how well I care for patients.

Paul…so very well written, as always!. In a world demanding evidence-based decision making and value-based healthcare, where is the evidence of value of MOC to patients or our larger healthcare “system”? ABIM’s Choosing Wisely campaign genrally encourages physicians to abandon those practices that have costs but no demonstrable value – would this rubric then be generalizable to MOC? Asking for a friend (thousands of them).

I finished residency same year as you. Passed IM and cardiology exams three tims, add 2 ABMS exams each for echocardiography and nuclear cardiology you are in an endless cycle of testing. For the latter 2 I can even muster some rationale for interpretation of difficult images, if it is done in an appropriate environment, including high quality monitors.

My biggest issue with ABIM is the appointment process of their boards. Why don’t we, the practicing physicians have a voice?

Fifty years and a day I practiced as a provider (formerly known as a Family Physician) until retiring on the first of July this year. After my first ABFM certification examination in 1976, I was reexamined every seven years until later I was reexamined every ten. After I was examined and certified in Sports Medicine by the ABFM in 1993 when the CAQ was first offered I have been reexamined in that discipline every ten years. I am now able to maintain ABFM certification with LKA and will continue to do so, using the process as an opportunity to learn and also assess my own knowledge or ability to search the net to quickly find answers. May or may not assess competency, but always interesting and I always learn something. I will not address costs in this comment.

Considering the vast body of knowledge that is medicine during my recent fifty year class reunion, I pondered this question. How and what does a Medical School choose to teach students during their short/long four year degree program? And how do the net and electronic databases complement or replace knowledge? My physician father, wiser now in retrospect of course, counselled me as I was applying to Med school, “It doesn’t matter which school you go to. Any one will have more to teach than you can learn.” With the shortening of doubling time and exponential growth of medical knowledge, omitting here a discussion of wisdom, his counsel is even more appropriate for today’s student doctors. Daunting is the task of teaching and learning. But as Cirrus Aircraft encourages me as a pilot, “Never stop learning”.

G Ruffin Benton III MD

UNC School of Medicine 1973

But about the concerns that the profession is not self regulating well enough? I have retired, to rural US caring for my 99 year old mother, and it feels to me that medicine here doesn’t get much feedback for poor practice or good practice although the docs are presumably staying certified to get paid by insurance. ???

Just end the MOC! It’s time for a change

Another insightful article by Dr. Sax.

I feel guilty commenting at all as I am grandfathered in! My younger colleague unfortunately is not and is quite annoyed by the periodic necessity of the MOC. About 20-25 years ago or so I decided to get my added qualifications in geriatrics due to the “aging population” but when the 10 year renewal came up I just let it slide – as I was still boarded in IM. Funny thing- when younger patients saw I was boarded in geriatrics they asked if they should be seeing somebody else! I removed geriatrics from my cards and letterhead and my older patients don’t seem unhappy. I don’t think the “loss” of my geriatric boards had an effect on my ability to care for seniors!

I am doing a 18 month long MKSAP 19 review with another colleague and even though I don’t have to submit the answers anywhere other than the MKSAP, I still stress about submitting an incorrect answer so feel for everybody who has to answer multiple choice questions in the conditions described by Dr. Sax.

I have been following the recent uproar over MOC and this is another article that accurately addresses this issue.

It sure would be nice if IDSA took a stance on this issue or even asked the members their opinion on the issue; so far they have been silent.

When I wrote my book on health care, I devoted an entire chapter to the fiasco that is MOC. I have yet to get a satisfactory answer from ABIM to the most important question. What exactly is ABIM assessing with the recert exam, be it traditional or LKA, other than a physician’s test taking skills and their knowledge at one given point in time? It certainly does not measure a physician’s ability to care for patients or their knowledge even just 4 weeks later. And why do they insist on a timed assessment? Their rationale for that is an absurd one. Perhaps if ABIM removed the timed component to the exam, physicians could actually read about subject and learn, rather than reading just enough to answer the question, before moving on to the next question. ABIM could then argue that recertification provides educational value and that what they are trying to measure is simply due diligence. However they have refused to do that as they see themselves not as educators, but instead as the self appointed enforcers of the medical profession. I refused to bow down to them and opted to retire instead.

Mark, I heartily agree. I, too, “just missed” being grandfathered…and resent the time, energy, money and emotional hit (feeling inadequate when material tested has nothing to do with 80% of what I’ve been doing in primary care internal medicine for the past 30 years) recertification takes on me. I refuse to do my 4th re/certification come 2025 and will just maintain my NBPAS certification. Thank goodness I now work for myself!

4 minutes? That’s luxury!

For my PM&R boards, I have 2 minutes per question. For my subspecialty Pain Medicine boards, I have 1 minute (yes, that’s right, 60 seconds) per question.

I vowed never to study for the MOC exam, counting on my general self-education through reading journals, conferences and so on to pass the test. I congratulated myself when I passed the test with mediocre scores for my initial certification and four more times after that. I congratulate myself more when I succeed in keeping up with the ever-changing world of medicine through continued self-education. My clinical competency and continued education on a day to day basis is what improves day to day patient oriented outcomes, not studying for a test every ten years, or even doing question banks that are written by physicians who do not know the nature of the patients I see on a daily basis. I think we should demand data that studying for such an exam or taking a course to improve one’s scores improves day to day clinical competency. Dr. Sax’s well written overview of MOC is an excellent reason to abandon the draconian process of MOC.

Thank you, Dr. Sachs for another insightful article!

I have also recertified six times so far, three for internal medicine, and three for Infectious Disease. The activity that gave me the most pleasure and help me learn a tremendous amount was taking the Gorgas Course of Tropical medicine in Lima Peru 5 years ago. I greatly enjoyed the teaching, the patients and the new connections with the other course participants. However, I had to take unpaid leave from my practice to do that. I was told that Norway allows its physicians to have every seventh year off as a sabbatical. Wouldn’t that be wonderful? To have health insurance or the US government fund such a year- with some CME requirements?

First, as a family physician, I feel the medical profession is owed an apology on behalf of my specialty, which founded the Church of Our Lady of Perpetual Recertification in 1969, trying to achieve credibility for a new specialty of generalism and to differentiate it from general practice. Other specialties eventually got on board with the concept of repeatedly proving “quality” by passing a written test and then MOC became a thing – we need to prove we’re always good, not just cramming for a test once every 7 years, right???

Alas, there was never good evidence for recertification or MOC maintaining or improving quality – much as the evidence for the benefits of CME on quality are quite modest. Part of the problem lies in our continued difficulty in defining and measuring quality in medicine; it remains closest to Potter Stewart’s famous definition of pornography – “I know it when I see it.” Most of our alleged quality measures in medicine have little validity and are defined more by what is easily measured than by what is important. Preventing readmissions? Oops, not so simple. Cancer screening test performance? Mostly should be a function of the system and not a measure of a clinician; our role should be at the margin, only with patients who probably should do it but don’t respond to system efforts. Etc.

When someone asks me if X is a good doctor, the only way I can give an answer is if I have worked with them fairly extensively (and if my judgment can be trusted). And peer ratings have many issues of their own. The best I can come up with would be a combination of multiple measures, including patient satisfaction if and only if only if large samples with high response rates (sorry, Press Ganey) can be obtained and are adjusted for relevant patient factors, valid outcome measures for common activities of the specialty, again with appropriate adjustment, and random, unannounced visits by standardized patients. And maybe truly confidential/anonymous surveys to close care team members asking how likely they would be to take a family member with a relevant serious illness to the clinician.

But none of my suggestions has any chance of being implemented, even if tested and shown to have reasonable predictive validity. (And for what outcomes?) So we are likely to continue tailoring the emperor’s quality clothes.

As always, if you want to assess the true motivation behind an organization like the ABIM, follow the money. From their website, their 2022 revenue was $71.9 million, expenses $58 million, exam administration/oversight/development add up to 50% of their costs. That’s a lot of fat on top of the actual test we take and pay for. In case you’re concerned about their leaders missing out on the excesses clinicians enjoy, you’ll be happy to know that their President’s total compensation from the ABIM and “related organizations” exceeded a million dollars last year. Furthermore, if you are concerned about the economic wellness of the ABIM, the ABIM Foundation lists $181 million in assets as of 2022. Personally, I could live with the notion of ongoing knowledge check ins and/or periodic testing to keep us on our toes but I can certainly live without the excess annual tithes we pay to a very fat organization that seems very self serving.

I am not an internist, but my specialty has a similar process. IMHO a process that has no method by which to assess whether or not it is achieving its goals is unethical. Would we be willing to conduct a clinical trial which involves any risk at all to a patient without having an assessment of the trial’s outcome? Is this process really so much different?

Some specialities offer the opportunity to “tune” the exam to one’s practice patterns. This at least reduces the risk (to the physcian) of a process which has no method by which to assess efficacy.

During the shutdown I binged on ABFM’s online CME. Each module’s 60 questions requested feedback. About 5% of the questions had no right answer. There were a lot of questions more than 10 years old and a few pushing the turn of the century. I could find no sign that the Board paid attention to comments, but it was obvious that every year or two someone would delete them. With time on my hands, I started writing increasingly snarky comments, sometimes in limerick form. I got a call from the CEO, he’d been on the job for 6 months. I told him, truthfully, that a team of 10 practicing docs could clean up the 60 KSA questions in less than a day. What if a bunch of us went to Lexington, and in a show of disgust, each paid our fees in $1 bills? Or if there were enough of us, held a 60s style (peaceful) demonstration? Timing would have to be right, though, or we wouldn’t get national coverage.

Buying tests till retirement does not improve patient care.

The author created an amazing and recognizable summary. Will not repeat all this but recognize very well what he describes.

What I find an additional miserable thing is the completely vague criteria for what counts as CME and what as MOC.

Just paid some $ 300 to review multiple issues and debates during DDW. Evaluated everything and was awarded some 30+ CME points

Reviewed also all presentations of postgraduate course, evaluated etc. No difference in set-up or quality from many outstanding presentations and debates during DDW In the end only MOC if I added another $300. Then update of annual ABIM fee of $220 .

Is one then surprised that some believe that this is mostly a money business?

I started taking the ABIM Exam when they first said lets have an ABIM exam. I had already finished my residency in Nephrology and could not possibly have passed an ABIM exam, yet i took it all of my adult years, passed it once even though it had nothing to do with my medical practice nor was it related in any form !!! I finally decided that i wuld not spend the remaining years of my life taking this exam only to fail it. I had better things to do with my remaining years. I became a member of the NATIONAL BOARD OF PHYSICIANS AND SURGEONS ( the alternative ABIM) because I could prove that I was keeping up with relevant information in the field of Medicine. Fortunately my ” Clients” did not seem to care whether I was ABIM certified or not, so long as I gave reasonable, logical and proveable ( ? ) answers to the questions they had asked for.. The ABIM is just a way to make the authors rich at the mercy of those of us who are trying to survive. !!!

At some point there will be a legislation at federal as well as many states level for needing board criteria for docs to participate in the network, insurance provider, hospital staff privilages. Individual networks can set up the standards for renewal based on direct monitoring right under the nose.

If all the docs ignore the test just one year, communities driven legislators will step in to fix the Medical boards money making irrational testing methods.

How about setting a criteria for the board members & test givers have to pass their own damn made up difficult tests!!!

The current testing need overhaul.

I am in solidarity with the colleagues who have contributed so thoughtfully to this blog. Author, educator, and practicing physician for 50 years, here is a short excerpt from an article I wrote earlier this year:

“I am currently studying for my board recertification—and you know something… so far not even one review question addresses food and lifestyle. Instead, every one deals with drugs, dosing, and procedures.

Because I don’t rely on memory for this type of information, I searched for a reference program where I could quickly (in 4 minutes or less) look up such data and of course was led to the most common resource with over 2 million users worldwide: UpToDate. I remember buying the program 35 years ago when it was sold in a disc. I found the current version very efficient and organized regarding symptoms, drug treatment, and dosing. However lacking, just as it was then, in nutrition, medical prevention, recovering health, non-commercial food centered dietary education for the patient, or lifestyle interventions. In fact, some of the references on diabetes and heart disease are quite dated (they stop around 1990). However, explicit bogus caution regarding incomplete amino acid composition of plant diets and generous industry guided recommendations on the consumption of dairy products, abound.” No mention of recovering insulin sensitivity or reversal of coronary plaques using the evidence based published medical research that relies on food and lifestyle—some such programs are even paid by Medicare.

I, too have been going through the motions of getting re-certified, while practicing the most excellent care that I can, which renders my patients capable of recovering health and not just the subjects of disease management that that is emphasized by the current medical paradigm.

We must acknowledge that the fastest growing medical specialty today is lifestyle medicine—rather than dig our heels and perfect a draconian way of testing our competency to manage disease by prescribing drugs, we should join forces and focus on improving patients actual health outcome through all the pillars of health at our disposal.

I stay engaged for the sake of my patients and the next generation of physicians.

I quote “grandfathered” with Internal Medicine and Cardiology certification through the American Osteopathic Board of Internal Medicine. In 2002 I began 1en-year certifications and recertifications in Nuclear Cardiology, Adult Transthoracic Echocardiography/Stress Echocardiography/Transesophageal Echocardiography, Advance Intraoperative Transesophageal, and Vascular Interpretation, RPVI. The studying and testing for each certification improved my “quality” in each of the areas being certified. Since these certifications were for “cardiac tests”, interestingly the certification testing process did correlate with these parts of my cardiac practice. So perhaps physician certification of clinical diagnostic tests may be a model to be considered in an effort to match other physician certification to clinical practice.

Unfortunately the location where I interpreted these cardiac tests frequently could be described as: “These rooms are gloomy, windowless, and airless places . . The rooms are filled with side-by-side desk cubicles. Each desk has a monitor, keyboard, and mouse.” So the alternative approach to physician certification needs to avoided: Physicians spending their entire “clinical” day just at the desk cubicle with a computer evaluating each patient case “for 4 minutes” which instead of aligning MOC and LKA with the physician practice, the physician practice would be aligned with the present MOC and LKA.

I am probably a renegade, an outsider, a resistant to the status-quo; But my ABIM board expired in 2001; And I refused to repeat it anymore; I will NOT allow myself to be held hostage to the bunch of extortionists and simply be financially at their mercy; To hell with them; I am able to find my way on the outside; I read assiduously on my OWN TERMS because I enjoy reading and learning; Too many Doctors have been too timid and docile for far too long and thus held like a puppet on a string; It feels great NOT carrying the yoke of the ABIM/MOC.

One would believe that before imposing a costly and onerous requirement on physicians any organization would provide objective evidence that the process and procedures resulted in actual improvement in outcomes of clinical care. There appear to be be no such data, at least that I can find. Meanwhile, it has become clear that the ABIM finances have greatly benefitted from the endeavor.. For example, in 2018 the president of the ABIM earned nearly $650,000 and with “additional benefits” compensation totaled $1.1 million. To my admittedly skeptical eye, money seems to be the driver for these endeavors.

It’s amazing, I am reading this and everything my profession is doing mirrors what you’re discussing; including the take home questions by the way that are sent to you quarterly. The amazing thing is people feel the same exact way. There is one big difference between physicians are doing and what the P.A. profession is asked to do. The P.A. Profession must basically take an exam. that mirrors our initial certification exam we take upon graduation . So one must go back and study not only what they do day-to-day which could be thoracic surgery or neuro/Alzheimer’s disease or dermatology or good old family practice, but get tested in all of those things plus emergency medicine and internal medicine and more. How would you like to be a psych PA for 25 years and pass an exam that asks you how old little Jimmy must be before he can eat solid food, or what does this microscopic specimen say about the vaginal symptoms this woman just walked in with? To many of us it feels pretty much insane. I’m sure for those of you reading. I hope whomever is left reading the comments would agree. We certainly have some work to do. We also have those onerous board prep courses that people make significant revenue from, and in some states PAs cannot practice, or or at least are eligible to have their license is revoked , if they are not currently board-certified. I’m not sure how many chances one gets to pass the boards but certainly there have been people who had to move to other states to practice. Taking your initial med boards after 10 or 20 or 30 years in practice would be total insanity for most physicians I know. So whenever you’re thinking of how tough it is, just remember us.

Paul, thanks so much for writing this. It was brave. I keep reaching out to our state ID society and the IDSA to respond in some meaningful way to these concerns.

Once we are board certified after residency we should be certified for life. Recertifications shouldn’t affect that status. Doing CME or perhaps doing board questions like MKSAP to update our knowledge and to keep up with evidence based medicine in a non-punitive and in-expensive way should be the way going forward.current ABIM board exams/MOC is too expensive and time consuming, that adds to our burn out.

I am a night shift hospitalist. I was taking the MOC exams in internal medicine and infectious diseases. The MOC internal medicine exam had lots of clinic, preventative, and cancer screening medicine, which I do not do. I took the Hospital Medicine MOC exam and that was equally unrelated to my work as it was mostly pre-operative medicine. That is not done during night shift. The only night surgery at the hospital is emergency surgery. No one has ever asked me to clear a patient for emergency surgery.

After completing the Hospital Medicine exam, that certification exam was stopped. So now I will retake the Internal Medicine exam as in a few years no one will have heard of a Hospital Medicine Certification. I love medicine and will also do it as a hobby. However, I would rather be reading about what is relative to my patients and writing up case reports for publication than studying for MOC exams.

CME for is required at too many levels: Board certifications, State required CME, CME required by the hospital system, CME is now required for DEA licensing, and in addition I do the CME for my other State license, Clinical Laboratory Scientist. Board certification is too expensive and is paid for by my employer, the health system, which then increases the cost of the patient’s insurance.

Let me start with saying I am a huge fan of yours. And really enjoy your blog.

I felt like my last ID recertification exam was the most clinically relevant to my practice than any of my medical exam that I have taken so far, except few questions reg transplant ID, as I do not practice transplant medicine.

I wonder if we can use AI to decide how to make a test that is more relevant to one’s practice. For example, it goes through all the billing Dx code for that doctor in last 10 years and recommends in what areas that doctor need to continue maintaining knowledge. And that exam is self-learning, where it helps them improve and gives them new information and new data that has come up in last few years that are practice changing.

Second, if someone really only practices specialist clinical practice, do they really need to go through Internal medicine recertification exam ?

LKA, obviously the best route to go now that it’s available, is still onerous. And as far as I can tell, it’s essentially testing our web-searching abilities.

Thank you for writing this, Dr. Sax! You forgot to mention ABIM’s attempt to foist maintenance of licensure on us. I fully expect them to try again.

The problem most of us have is that we’re employed by health systems that are run by business people, and they force us to continue to take these useless exams. I would love to opt out, but I’d lose my job. No question that this problem requires coordinated action by physicians. I’m in!

CME is all we need. The ABIM could be useful if they decided to be, but they make too much money to give up what they’ve got without a fight.

Colleagues,

“Endless certification in medicine” is one of the most interesting and thoughtful essay written with some humour in my opinion. I’m an ID physician in academic medicine teaching and treating patients since completion of training in ID about 33 years ago.

Fortunately I’m “grand fathered” in IM but not ID. Have taken ID certification exam every 10 years since and currently enrolled in the LKA which began in January 2023.

A few years back, ABIM personnel started an email thread to comment and critique on there work and the the discussions ended up being on the recert exam requirements and 99% of physicians were absolutely against it. Some top brass from ABIM tried to defend their enforcement of recertification and the hefty fees that was forced on us. None of the reasons given by ABIM for the need for the recertification was because ever valid and proven except for some data collected by ABIM, I’m sure was paid by the fees we paid them.

I do not believe there was any independent body validating the examination.

How ever, if I’m not mistaken that site for comments was shut down.

So here I am, over 30 years since my original certification, required for maintenance of my academic title and clinical privileges. About 50% the questions in the exam are on areas of ID that I rarely or never see.

I plan on continuing practicing clinical medicine and teaching as long as I’m physically and mentally capable as I enjoy it as well as the income and other benefits I receive.

Hopefully the “Endless” torture forced upon us by the ABIM will “End” soon.

I think taking these exam is a waste of time and the only benefit of it is for the ABM where they can collect money. Last time I looked at the AIM. It was a business entity, so they care a lot profit and loss, I think it is waste of time.

I am enrolled in the LAK and I’ve been encountered a lot of questions. That’s the answer differ from UpToDate as their source for all the answers, and I submitted these questions to ABM but unfortunately, I never had any follow up or explanation about them choosing that and I’ve been encountered a lot of questions. That’s the answer differ from UpToDate as their source for all the answers, and I submitted these questions to ABM but unfortunately, I never had any follow up or explanation about them, choosing the wrong answer.

If you think MOC is onerous note that now with the passage of the budget reconciliation act last year there is a new requirement to do 8 hours of training in treatment of drug addiction in order to renew your DEA license. This is because more clinicians are needed they say. As if 8 hrs would truly be enough and as if a general internist could possibly take on this treatment in his/her practice. This requires a multidisciplinary team.

Once I read the word “grandfathered in” I had to laugh.

A few hours ago, I had this same conversation with my 90 year old mother, who graduated first in her class at Hunter college and then became an anesthesiologist bearing four children . At that time the men chastised her and said,” what will your children call you?” I then tried to explain the outdated philosophy of the ABIM towards recredentialing.

I reasoned that lawyers do not need to recertify every 10 years .why should physicians ? Could the ABIM be making money at our expense? Could this be part of their Job security ? There is no scientific justification for the term “grandfathered in”. I have taken the boards several times, and I will never take them again. There is no test equivalent for dedication, experience and knowledge. I participate in required (and necessary ) continuing medical education .

I found this article quite informative and with good humor as is typical of the author! I completed my fellowship in 2010 and was due to take the 10-year exam in 2020 – and had prepared for that but COVID canceled those plans and I subsequently enrolled in the LKA. I have found the LKA is an exercise in academia and has minimal real world applications. I have to answer a question in 4 minutes – I really don’t understand why I can’t have all the time I want to answer a question as in the real world I can spend as much or little time as I need to address a complex clinical situation that I may encounter. However with that said – I don’t mind answering a question and getting immediate feedback but alas this is more academic to real world applicability. Perhaps there has been on an occasion where I learned something that would change my practice.

I learn more by reading CME articles and attending ID week. I don’t think MOC – weather 10 year test or the LKA should be used to determine if you are clinically competent to practice medicine. I hope the IDSA will take a stance against the ABIM and this continuous recertification cycle.

Since I completed medical school in 2004 I have seen an erosion of our profession that is quite appalling. (I am sure those older than I have seen the rapid change even more than I). We allow non-physicians to do our job, we allow non-physician business people to dictate what we do clinically, we allow insurance companies to dictate what tests we can and cannot order (yet we take the medical liability) and we allow the government to dictate onerous EMR requirements that don’t improve healthcare what so ever and allow them to decrease our reimbursement year over year. We have also allowed our profession to be degraded – we are now providers instead of physicians in the eye of almost everyone. See article: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8560107/

In my own area – physicians have left and can’t be replaced and instead the health care entity chooses to replace with a APP – as if that is the same as a board certified physician. If I refer to a specialty for some of my complex HIV patients – sometimes they don’t even get to see the physician – they see a midlevel instead (who usually repeats the work that I already did). Over the last couple of years the urgent cares and ED have change greatly – my system refused to renew contracts with several physicians instead opting to hire APPs so that the ratio of physician to APPs is 1:4 – apparently this is the new industry standard. It is quite frustrating – the quality of work-up in ED and urgent care has degraded.

Unfortunately physicians are to blame for a lot of these changes. We train APPs and we allow non-clinical entities to dictate to us and erode our professional judgement and we accept working longer hours with less pay and using an EMR in which we are over glorified scribes to define our work. You would have thought with COVID that the health systems would value the ID field – it is more or less just lip service. We also run ASP and IP committees but they always want us to do more with less and both fields are chronically understaffed to begin with.

While I am as liberal minded as many ID doctors tend to be based on surveys and I live in a conservative area – frankly I think we physicians need to form a union. We could bring the health care situation to a standstill and really drive change. We can stop the onerous MOC requirements, the onerous EMR requirements, insurance denials, pay cuts and yes expansion of APPs scoop creep almost immediately overnight by striking. Frankly the AMA, AOA, ACP, IDSA, etc are all fiefdoms and don’t all speak with a unified voice nor do all physicians belong to them. We need a union that represents our interests and counter these intrusions on our lives and profession and by standing united we can. Alas this will likely never happen as that would require us to stop seeing patients – which might cause harm and we are very altruistic and pledge to “do no harm” even if it is to the detriment of ourselves. I will speak for myself but as it stands now – COVID has really changed the paradigm – many of us our burned out (I consider myself one of those) and I frankly long for the ability to retire. I am a mid career physician however if a better opportunity came my way I can see myself leaving medicine in the not too distant future unless things were to change for the better.

One of the great percs of cognitive work (ID) is the absolute requirement to be a lifelong learner. Paradigms change. How can we keep ourselves current if not some objective mandated exam. I am grandfathered in IM but took one recertification voluntarily. I always learn form the pricy board review course and the scope of my practice keeps enlarging so I am grateful to have email access to some great teachers from board review. But in most clinical scenarios there is no right answer. Our thoughtful judgements based on data and clinical context is what differentiates our quality. The multiple choice test is practical. But essay type questions would better capture our ability to write a good consult.

As an anesthesiologist, I’m perhaps a bit out of line commenting here, but I had to laugh when I saw the complaints about “four minutes” to answer a question. The Board of Anesthesiology came up with “MOCA Minute” a few years ago. We pay $200-ish annually for this privilege (though it is not the only component of MOCA that demands a fee); we must answer 120 questions per year (30 per quarter). You get exactly 60 seconds to answer the question, hence the term “MOCA Minute.”

To be fair, it replaces the ten-year recertification exam, which I’ve also done. The MOCA Minute is but one of many of a dizzying array of ever-changing requirements (quality-improvement projects, medical simulation and the like) that must be met in order to maintain certification. I’m on my third MOCA cycle and the requirements have literally never been consistent for any of the cycles because the Board keeps changing them, including, most recently, announcing that certification will now last only 5 years. Luckily for me, this announcement was made shortly after I received my latest 10-year certification, and there will be no fourth cycle for me.

It’s time to end MOC.

The way that the questions “differentiate” is not due to some breed of intelligence, it’s the way the questions play the “what am I thinking game”. And no matter how well intentioned, the metrics push these types of questions the most. Many of those questions are misleading, and the writer often doesn’t grasp that their intended answer is often accompanied by another answer that was, is or could also be correct minus some trivial detail. The addition of so many “test” questions just makes the experience worse.

The other worst part of LKA is that there is no way to study. Unlike taking a course to learn all you can for that 0ne point in time…you have no idea what subjects the 30 questions will have. There is no way you will study all of board review for just 30 questions, every 90 days.

I once took the educational products and tests for my GI society. I recognized that they asked questions pertinent to important changes in my field. But how was I supposed to have seen this one paper, this one review?? They showed it to you after the questions. I then read it, realizing it was pertinent and valuable.

Why are we treated as children? Instead, give us that important paper quarterly. Ask us questions AFTER we get to read it. Give us CME for doing so. End this childish game.

got out of the rat race to work for county as health officer. decided at that time that i would explore other options that the AOA’s longitudinal assessment process. See, the osteopathic powers that be became jealous of the money the ABIM was generating, and followed suit. We argued this, and now no longer do the practical OMT as part of our recertification exams, and when we grumped about the cost..a short time of a lower cost for the AOA, that is now back to where it is. These concessions were easy, as the real money was the nickel and diming of us with the long range assessments the 1,000/year of paying for this that many of us get with our CME funds. SO…NBPAS for me. Thank you guys, for making another path.

The goal of the ABIM is to make money, the excuse is the welfare of the patients and the victims are the hundred of thousands of physicians who have to pay to be abused by a board that is accountable to nobody.

I have taken the IM board three times and the ID board three times, and I am not better for it, nor have my patients experienced better outcomes because of it.

We all know this, yet we are forced to participate in this pathetic charade.

I began to re certify my multiple boards in Psychiatry December of 2015 through National Boards of Physicians and Surgeons. I believe this is much more fair and less expensive. Specialists can study their area of expertise and submit evidence of their CMEs.

The ACGME does not recognize this MOC organization yet.

I stand with NBPAS(Thank you Dr Tierstein) and encourage everyone to investigate this option at http://www.nbpas.org