An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 22nd, 2024

Brave New Name — How PCP Became PJP and Why It Matters

In the pre-E**n M**k era of the site then known at Twitter, I posted a poll about a very important debate in clinical Infectious Diseases:

That’s right. Nearly 900 people took the time, energy, and clicks to weigh in on the critical question of what to abbreviate the well-known opportunistic infection in immunocompromised hosts. Fifteen commented further — including one Sam Saks (no relation), who is not to be confused with Sam Sax, the DJ and saxophonist (also no relation), or with Sam Sax, the brilliant young poet who just happens to be my nephew and who was nominated this year for a National Book Award. Way to go Sam!

So it’s clear that this PCP vs. PJP debate is indeed an important question. It easily ranks up there with similarly life-changing debates such as what syllable to stress with cefazolin (second? or first and third?), whether to start calling Streptococcus bovis one of its many new names, and how to abbreviate tenofovir and emtricitabine combination tablets — are they written TDF (or TAF)/FTC, as is usually done in treatment studies, or F/TDF (or F/TAF) as in PrEP trials?

(That last one drives me crazy.)

The bottom line — people clearly care, and want to know, whether Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia is PCP or PJP.

It’s worth reviewing some history here, a story perhaps unfamiliar to you young whippersnappers out there reading this on your newfangled phones. For many years, especially the early years of the HIV epidemic when this pneumonia was so frequently the sentinel event in someone diagnosed with AIDS, the organism was called Pneumocystis carinii (not jirovecii) and hence the pneumonia was readily abbreviated PCP. It’s the acronym, after all.

Pneumocystis carinii got its original name from Brazilian physician and scientist Antonio Carini, despite the fact that his Pneumocystis-related research included two mistakes. In 1910, when he sent samples of an organism he found in the lungs of sewer rats (!) to the Pasteur Institute in France, they confirmed his aspirational claim that he’d discovered a brand new parasite. Turns out he wasn’t the first, and it wasn’t a parasite. Oh well.

Mistakes notwithstanding, he happily took credit, and could brag to his friends and family that he had achieved taxonomic immortality. The name stuck around for decades. It also made him feel better about the fact that he was studying such disgusting animals — rats are bad enough, but sewer rats? Bleh.

So to us ID doctors of a certain age, if you said “PCP,” it meant Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. It’s right there in the first sentence of the original report of cases of AIDS, and reappeared thousands of times in the medical literature over the next 20-30 years.

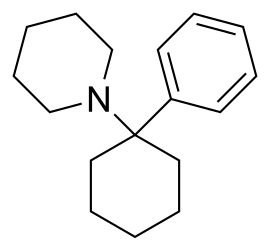

To us, PCP did not mean phencyclidine, the hallucinogenic drug more commonly known as “angel dust.” Phencyclidine still gets the top spot in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, and, if you’re wondering how you get PCP out of a word with only one “p,” it comes from phenylcyclohexyl piperidine, the full chemical name. In other words, this:

The chemical structure of phencyclidine, in case you want to try making it at home.

The other common medical use of “PCP,” of course, is to designate “primary care physician” or “primary care provider,” terms used with staggering regularity in clinical settings and healthcare policy. Sadly, the frequency of use of PCP for this meaning is inversely proportional to the number of PCPs who actually accept new patients in the Boston area, never a good sign.

Back to Pneumocystis carinii, though I hope you enjoyed that scintillating digression on the other meanings of PCP. (My mind wanders on these beautiful autumn days.) Several advances in molecular diagnostics, led by British researcher Dr. Ann Wakefield, allowed scientists to dig deeper into the genetic structure of these organisms. They discovered two important things — first, that Pneumocystis carinii was a fungus, not a parasite. Imagine, for a moment, that you find out you’ve been demoted to a fungus — no doubt little pneumocystoids everywhere required plenty of sympathetic counseling.

The second thing they learned was that the genus Pneumocystis has a whole lot more genetic diversity than evident just by looking at these critters under the microscope. There are several distinct species, and they target the lungs of different mammals — they’re species-specific opportunists. If you’re a rat, you are probably not reading this post; more importantly, you are susceptible to at least two species — Pneumocystis wakefieldiae (guess who that is named after?), as well as Antonio Carini’s claim to fame, Pneumocystis carinii.

That’s right — the organism we had been calling Pneumocystis carinii in humans was actually a rat fungus, which sounds an awful lot like an insult shouted at your bitter enemy (“You are nothing but a lowly rat fungus”). More importantly, the human Pneumocystis was genetically quite different, and in hindsight this difference might at least partially explain why animal models of infection cannot fully represent what happens in humans.

Example: When I was an ID fellow in the early 1990s, I heard famed Pneumocystis guru Dr. Walter T. Hughes give medical grand rounds. (That’s what everyone called him — “Oh look, here comes Famed Pneumocystis Guru Dr. Walter T. Hughes.”) The primary topic was an exciting novel drug named 566C80, today known as atovaquone.

(Boy, I had to dig deep to drag up that 566C80 from the memory banks. Dig deep = quick Google search.)

Hughes described vividly how corticosteroid-treated rats not only had insomnia, hyperglycemia, and puffy faces, they also developed Pneumocystis pneumonia. In rats, this infection was exquisitely responsive to atovaquone — it was the most active drug in his experimental model, much more active than trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX). Round-faced rats everywhere celebrated at this imminent great advance in medicine.

Alas, atovaquone is kind of wimpy against human Pneumocystis, and is not considered first-line therapy. A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial in HIV-related disease demonstrated lower efficacy of atovaquone compared with TMP/SMX, the opposite of what Hughes found with his rat model. Possible explanations included the Pneumocystis species difference between rats and humans, the poor absorption of ATOVAQUONE TABLETS in humans, and well, that humans are not rats — at least not outside the world of politics, where there appear to be rats everywhere.

Careful readers, especially ID docs and pharmacists, might have been startled to read “atovaquone tablets” in the preceding paragraph, and not only because I left on the all-caps key. I did it to remind myself that the poor absorption of this original formulation is why today, atovaquone comes in that distinctive suspension — the one that looks like yellow paint and doesn’t taste much better either. They make it this way to increase absorption.

But take a look at that icky stuff:

Atovaquone, in all it’s colorful glory.

Yuck.

But I digress. (Editor: You think?) In Part 2 of this post — and there will be one, you have my promise — you’ll learn how motivated scientists solved the problem that Pneumocystis carinii was a rat but not a human pathogen by designating a whole new species, Pneumocystis jirovecii.

But that was just the beginning of a brand new drama, a story so riveting that I expect it to be featured in theaters and on streaming services soon.

Stay tuned.

This post is both hilarious (and I’m not a doc) and a cliffhanger! (At EEOC, PCP stood for Priority Charge Processing, something created to clean up a mess left by Clarence Thomas’s tenure as Chairman of the Commission.)

I voted for PJP originally, can’t believe we lost.

“If you’re a rat, you are probably not reading this post” — you underestimate rats!

(Can’t wait for Part 2.)

Hilarious Paul. I understood that PCP refers to the disease-PJP the pathogen. No idea if that is right but….hope you clarify. Cell wall composition is different than other pathogenic fungi-something about rats?

Stay tuned for Part 2!

-Paul

Fun and funny and informative. Took me to read Hopkins POC-IT.

Also took me to Granta and a sam sax poem.

Thanks for all you do to educate and re-educate us with joy and humor!

Gordon, appreciate the comment — and the fact that you checked out Sam’s poems!

Reading that June 5, 1981 MMWR made me shudder, knowing what was still to come.

Agree, it’s chilling. But at least the story has become one of a medical miracle!

-Paul

p.s. I hope you found the rest of it entertaining

I wonder what % of us can pronounce “jiroveci” correctly (without Google)?

T

This column is classic Paul Sax, ID guru in your legendary glory, the type that I make my non medical husband read because it’s just that good.

Thanks for it! I can’t wait for part 2.

-a rare PCP of the non infectious type in the Boston area, who, alas, is not accepting new patients (I opened my panel for 4 days in September and ended up with 70 new patients—!)

Thank you for the pleasant reading. I would like to add that the first person to discover the agent was also the Brazilian researcher and physician Carlos Chagas (yes, the name behind Chagas disease). He mistakenly thought that the pneumocystis was a pulmonary stage life of his newly discovered parasite, which he named Schizotrypanun cruzi because of that. Lately, with the research of Carini, he was able to fix this mistake.

Love it!

This post reminded me of Lawrence Sterne’s, The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy. I’m won’t trouble anyone by explaining why.

As an English major, I am very flattered at this analogy!

–Paul

Paul this is hilarious…but I think the correct insult is, you are nothing but a lowly SEWER rat fungus.

Can’t wait to read part II.

How wonderful, entertaining, and nostalgic. I remembers the initial PCP, the change to referring to the disease rather than the organism, and now PJP. Looking forward to Part 2.

Marvelous!

I allow my residents to use “PCP” as it standing for PneumoCystis jirovecii Pneumonia. Checkmate microbiologists! I’m also of the opinion that if we don’t split E. coli (and Shigella) into a hundred different species, do we really need to do it to Pneumocystis?