An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 7th, 2025

Two Pandemics, Compared: Reflections on HIV and COVID-19

“Dr. Sax, what’s it like to have lived through two pandemics as an ID doctor?”

“Dr. Sax, what’s it like to have lived through two pandemics as an ID doctor?”

The question came from a brand-new intern during afternoon sign-out. I took a breath — because wow, were they different.

HIV: It Felt Like A Calling, One Miraculously Rewarded

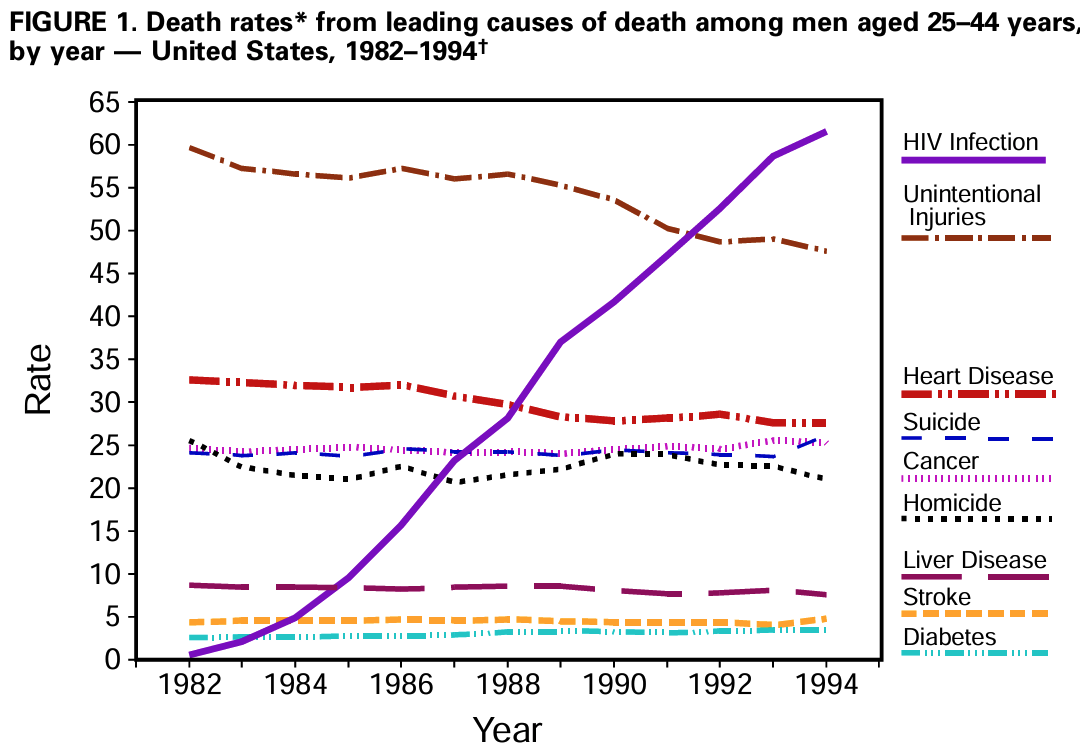

I started my internship in 1987, six years after the first cases of AIDS were reported. The median survival of someone newly diagnosed with AIDS was 12−18 months. When, at the end of my three-year residency, I chose Infectious Diseases as a specialty, part of the rationale was to follow what felt like an urgent mandate: HIV was about to become the leading cause of death among young men in the United States.

(I also liked antibiotics, microbiology, and taking patient histories about travel and pets. You know, the nerdy ID stuff.)

This catastrophic new disease taking the lives of young people in our country didn’t just present a medical challenge. The stigma was brutal. Many clinicians reinforced it by asking how someone acquired the virus, even when the information was in the chart or had no impact on treatment. “How many partners?” “IV drugs?” “Why didn’t you use condoms? I sure hope you do now.” Patients loathed the inquisition and the implied accusations; most of them already felt deeply stigmatized by their diagnosis.

One gastroenterologist, after doing an endoscopy, memorably told a 28-year-old patient of mine with candida esophagitis, “You don’t look like someone who has AIDS. How did you get it?” She remembers that 30 years later, and so do I.

It’s hard to convey just how ubiquitous, and punishing, this stigma was back then. “We can’t have those people taking up an ICU bed,” a cardiologist grumbled to me in 1990. Those people. Some surgeons looked for any excuse to avoid operating on a patient with HIV. Hospitals deliberately downplayed HIV as an area of expertise, not wanting to be branded an “AIDS hospital.”

I’m embarrassed to write that even some ID doctors followed this unfortunate plot line, expressing concern that HIV might ruin our specialty. Why take care of someone with advanced HIV disease when there was nothing that you could do to treat the underlying problem, the virus itself? Send them back to their primary providers for palliative care once you’ve treated the toxoplasmosis or pneumocystis, they argued. Small in number (fortunately), this group of ID doctors did not distinguish themselves during this period.

Because they were wrong. There was plenty we could do, and it wasn’t just diagnosing, treating, and preventing the opportunistic infections. We could also help alleviate chronic symptoms, manage polypharmacy, provide a longitudinal, compassionate care team, and — this part was critical — we could follow closely the research on antiretroviral therapy gathering steam in the laboratories and clinical trials.

When successful HIV treatment arrived in 1996, we could then celebrate with our patients the transformation of their previously fatal disease into something quite treatable. Rejoice!

Today, remarkably, HIV is easier to manage than many chronic conditions. In a quiet signal of triumph over the inevitable downward course of untreated HIV, residents who admit someone with stable HIV to the hospital — usually for a completely unrelated reason — list HIV way down on the patient’s problem list, something in the background that deserves mention but is rock-solid stable.

COVID-19: A 2-Year Siege That Drained and Divided Us

March 2020 reversed that script. Critically, this time, we ID folks weren’t alone; the whole medical center mobilized.

Energy to respond clinically was both collaborative and, at least initially, sustaining. In those first months, we worked together with critical care specialists, emergency room personnel, the microbiology lab, nursing, respiratory therapists — everyone on the front lines of patient care chipped in to get it right.

Another big difference was that, due to the mode of transmission, the fear was everywhere: every PPE donning felt like bomb-squad duty. Is it weak of me to admit that each time I entered the room of a suffering, coughing patient with COVID-19 in the spring of 2020 that my heart rate quickened? That I repeatedly checked my N-95 mask for the proper seal? Cursed with a giant nose, I had always considered this feature of my anatomy a cosmetic challenge, not a life-or-death issue — but it sure made fitting an N-95 mask difficult.

(Too much information? Sorry.)

I remember a woman from the Dominican Republic, struggling with COVID, telling me — through an iPad interpreter — that she drew strength from memories of going to church as a child. Her faith, she said, was helping her fight the virus. I listened, nodding, but from the far side of the room. The connection felt intimate; my posture and location, not so much.

Hallways were eerie and quiet — administrators were remote, many non-essential clinicians sidelined and doing only video visits, all elective surgery canceled, and family and friends of patients barred from visiting their sick loved ones. That last one was particularly heartbreaking. What a terrible time.

Then, the summer of 2020 teased us with a very welcome pause, as COVID practically disappeared from northern cities like Boston. Phew, time for a deep breath, everyone. I remember postulating hopefully, wishfully, to a close friend that perhaps the virus had already targeted the vulnerable, either from immunologic or genetic factors still to be determined; maybe it was done wreaking havoc on society at large.

I was so very wrong. The next 18 months brought us an autumn/winter surge almost as bad as the first one. Delta the following summer filled ICUs with the unvaccinated; Omicron then infected everyone else within weeks, making the Christmas holidays in 2021 a blur.

We in ID watched each of these waves unfold, following the scientific advances closely, and doing our best to communicate this knowledge to our patients and an increasingly weary public who just wanted this virus gone. Monoclonal antibody treatments came and went as the variants mutated — each antibody challenging to obtain with limited supply, and as difficult to deploy as they were to pronounce.

(It will be quite the trivia question one day to ask ID doctors to say, or spell, bamlanivimab, casirivimab, and imdevimab.)

Alas, our hard work put us in growing conflict with a world ready to move on. Anytime we modified our guidance due to evolving evidence as the disease changed, our words were seized as a signal we weren’t to be trusted. Ivermectin enthusiasm and anti-vaccine rhetoric spiraled into mass delusion. Two extremist camps battled it out in the press and social media — the group that insisted the whole thing was a fraud from the start versus those who refused to acknowledge that the disease had lessened in severity over time.

We knew that the truth lay somewhere between these two groups — yes, COVID was still with us, causing some unfortunate people to become severely ill or leading to Long COVID, but no, it was nowhere near the threat it was in the first 2 years. Somehow, conveying this message led to increasingly cantankerous pushback from both camps.

What began with a collaborative spirit to fight a global pandemic evolved into a political fracture that still hasn’t healed. It was the toughest 2 years of my career, and I’m still not over it.

Some Lessons Learned

Back to that intern’s excellent question, because in our workroom, I probably didn’t give it sufficient thought when I answered, motivating this post.

Yes, they were different. There’s no better example of how different than to look at what happened to Dr. Anthony (Tony) Fauci. Celebrated for leading the response to HIV, pilloried for the same leading role with COVID, he eventually needed a security service to protect himself and his family — one of the saddest commentaries on our divided world one could imagine.

But both viruses exposed societal ignorance and healthcare inequities. The best responses involved teamwork, compassion, rigorous evaluation of the latest research, and nuanced communication.

And both reinforced the fact that our work is never boring, that’s for sure. ID is still the best job in medicine, even when it breaks your heart.

Your statement re: COVID. “It was the toughest 2 years of my career, and I’m still not over it.”

Feeling thankful for your resilience and that you are still teaching, writing and showing the way to the current and new generations of clinicians.

“It was the toughest 2 years of my career, and I’m still not over it.”

This part got me. I’m not over it either.

I have only worked through one pandemic so far but it was so bad that it made me want to quit living. Antidepressants, a good therapist, and a 2-month sabbatical helped a lot. Now I include questions about resilience and how to cope in all my lectures to internal medicine residents so some good has come of it. I also no longer argue with crazy people but layout options and abide by their wishes. Thanks Dr Sax

“ID is still the best job in medicine, even when it breaks your heart.”

Amen!

I just finished reading The Great Influenza, by John M. Barry. One of the things I loved about the book is the way in which Barry makes clear that the political environment of the time influenced the response to, and even the acknowledgment of, the pandemic. I look forward to the day when I can read a book about the history of the COVID pandemic that takes a similar wide angle view. Unfortunately, I think such a book written today would be entangled in the still-ongoing “debates”, for lack of a better word.

The two extreme camps on the covid issue continue to frustrate me. Anyone who did any sort of patient care in 2020 knows it was horrible (and not made up!), and the same goes for how different things are today. Haven’t seen a case of severe covid pneumonia in ages, hope it stays that way!

Wise and sad words, beautifully expressed, as always. I am a non-doctor who always looks forward to this column arriving in my in-box.

Thanks for reading, Ian! Given your pedigree, you’d probably like this one about Conan’s wonderful father, Tom.

-Paul

Great piece Paul! Earlier this year when the TV show The Pitt got popular people started asking me questions about 2020 era COVID I felt very wary. I tried to watch The Pitt and only made it through a few minutes. No thanks, do not want to revisit! But I still agree with “ID is still the best job in medicine, even when it breaks your heart.” (swap in hospital medicine though!)

Thanks, Grace! Yes, hospital medicine took it on the chin in a big way during 2020 Covid — still remember your moving NY Times piece.

-Paul

Thanks for your great writing. And your dedication to patient well-being, dignity, and respect inspires and challenges your fellow physicians to elevate their practice to this exceptional standard.

Dear Paul: we are contemporaries, I went thru both pandemics with the same experiences and feelings. The great difference is that during COVID 19 I knew that I could get COVID 19 and be on a respirator like many of my patients, or worse my family members could get the infection from me, and end up dying. That was a terrifying experience, and I have not gotten over it yet either…

I loved that one. It was a great tribute to a mentor. Had no idea he was Conan’s father till the end.

Nice, Paul.

And now I toot my own horn: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2783500

What a great piece, Abby! Love this sentence:

-Paul

The politicization, misinformation, and widespread ignorance in the population are responsible for many of the deaths attributed to COVID-19. Even today, the ignorance of the anti-vax crowd is stunning.

As a data scientist, I was one of the guys producing SEIR models based on limited data for a number of county-level governments. Our models showed what WOULD happen IF actions were not taken. Actions were taken and the horrors predicted were never fully realized. Still, ignoramuses try to tell us “your models were wrong”. No, they weren’t. It was our actions that gave us a brighter future. These were the actions prescribed by the CDC, Dr. Fauci, and myriad ID specialists and epidemiologists. Well done!

I’ve been fortunate to have avoided any known infection by COVID. I was vaccinated as soon as I was able and have had a total of four shots with ever increasing adverse reactions. I’m not getting another shot due to my reactions, but I shudder to think how my body would have responded to an actual infection.

The HIV pandemic carried a label imposed by society. It was far more cruel, as it clearly showed that some lives were considered more valuable than others. COVID-19, on the other hand, was universal.

It is symptomatic that most replies don’t even mention the HIV pandemic, which is still ongoing—primarily due to a persistent lack of human rights.

Paul – Thanks for writing another moving piece. Having lived through the HIV pandemic in the 1980’s I find it almost horrifying that the closure of USAID programs in Africa is likely to bring on a resurgence of that awful pandemic.

As a general internist, I lived through and practiced during both pandemics. Everything Dr. Sax comments on reflects my experiences/thoughts. It is horrifying to see the vilification of Dr. Fauci, ID specialists, the CDC and the hard working medical providers as they seek answers for the benefit of all. I still remember the tearful expressions of joy and wonder when I examined HIV/AIDS patients early on. Had little to offer them at first but simple physician caring meant so much. During Covid, before vaccination, I was limited to telehealth then assisting in Covid vaccination clinics, but patients were again grateful to receive care and guidance. Many seem to have forgotten the early terror of Covid. I read every issue of your blog, Dr. Sax with eager anticipation. Your generosity, compassion and support (despite the obvious strain and pain ) are greatly appreciated.

Paul, thank you for another well-written, moving, thought-provoking piece. Your writing always hits the mark. I could not agree more with your final sentence. I wouldn’t trade this profession for any other.

Thank you Paul.

Our career timeline was only one year apart. As an ID attending, I recall the heartache of caring for patients who were dying. Although there wasn’t much in the way of guidance or treatment, I tell people that I learned to be a doctor before there were any medications for HIV. I knew I was making a difference. I tried to help people feel well and have meaningful lives as long as possible, with as little pain as possible. I was able to support them in their struggles on good days, and during the hard times. I was able to help families in their times of grief. My experience with COVID was completely different. In so many cases, there was no healing, there was no emotional support, there was no helping families grieve, or even allowing families to help patients die peacefully. Like many in the medical field, I felt painfully inadequate.

At the end of 2023, I started giving a lecture for house staff called “A Tale of Two Pandemics”, comparing and contrasting many aspects of COVID and HIV and reminding a new generation of physicians about the horrors of HIV. It’s interesting to see how many similarities there were.

I think I’ve reached my quota.

Caring for persons with HIV during the 1980s engaged every aspect of being a young physician. These included learning and delivering the technical aspects of diagnosis and therapy of opportunistic infections in a dynamically changing landscape of new tests, therapies, and guidelines; addressing complex emotional and social needs; bonding with patients, families, and significant others over their chronic course, celebrating successes (clinical recoveries from opportunistic infections) yet sharing their burdens as immune function continued its inexorable decline until an early death. This was time for learning and personal growth, developing empathy towards young people with a terminal illness, towards members of stigmatized and ostracized minorities.

My frustrations were primarily reactions to clinical challenges. After the recognition of AIDS in 1981, there was no known etiologic agent for 2-3 years; no diagnostic test for nearly 3 years; no antiviral therapy for nearly six years; and no durable viral suppression (enabled by HAART) for nearly 15 years. It was gratifying to begin treating patients with HAART in the mid 1990’s and to see them doing well into the 21st century.

After the first cases of COVID-19 were announced over the New Year’s holiday, I watched helplessly and with horror as the seemingly unstoppable catastrophe spread across the world and from both coasts to the interior of the USA. Local, state, and federal pandemic response plans that had been so carefully and painstakingly constructed after the emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 and SARS were severely challenged by the tsunami of COVID-19.

Part of pandemic preparedness that went right was rapid development and fielding of medical countermeasures-the prompt initiation of basic and clinical research and a streamlined regulatory process that enabled fast-track Emergency Use Authorizations. Diagnostic testing was fielded within weeks, vaccines (based on a novel and highly adaptable platform) within 10 months, and antiviral therapeutics within a year. Clinical trials of supportive care algorithms incorporating corticosteroids and immune modulators were quickly initiated. The rapid development of clinical practice guidelines and their wide dissemination was facilitated by the internet, a tool that was not available during the 1980’s.

I experienced the early HIV/AIDS pandemic as a front-line clinician, treating young patients with a chronic, progressive terminal disease in the context of painstakingly slow medical countermeasure development. My clinical role in the COVID-19 response was limited (giving vaccines), while my interests were on the broader aspects of response; these occurring in the context of unprecedented rapid medical countermeasure development. These contrasting experiences formed bookends of my ID career.

Thank you Paul for your insights.

In South Africa I was hopelessly overwhelmed by the early HIV pandemic. There was little time for reflection and we fell back on some very primitive coping strategies. (Denial of the personal effects of this wave of pain and suffering would be one of them). I do not think I learnt anything positive from this. Antiretrovirals changed everything.

I returned to the public sector in time for the second pandemic and it was different. There was far more fear and uncertainty initially. Degrees of denial soon resurfaced, pardoned by the recognition that COVID was merely one of many ongoing pandemic waves that our population was facing. Why panic about COVID in the face of HIV/TB/DM/Trauma etc? We were numbed enough not to overreact, adjusted our practice, redirected some staff and got on with the usual job of running MOPD, ROPD, DMOPD and daily/post-intake ward rounds (with a little added attention to PPE).

We were used to losing young patients, this had prepared us for the new wave of admissions. There was no time for heroism.

Clinical medicine has challenged me in a multitude of ways. I have had to grow, thicken my skin and adapt. These two pandemics will be judged by history for the failings and successes in our responses.

Paul,

This is an elegantly written piece that captures some of the experiences that bookmarked my careers and that of many of our friends and colleagues. I wish I could express it as well as you have.

I started my medical residency on June 26, 1981, and that night we admitted a young man with PJP pneumonia and vision loss due to CMV retinitis. Watching him die of an then barely described disease, and watching his family unable to come to terms with his sexuality, even on his deathbed was, in hindsight, a life changing event. Caring for people with HIV and working on clinical trials changed us. It made us hold two truths in our minds at once: 1) Our goal in medicine is “to heal sometimes, to ameliorate suffering often, and to care always” in the face of of an incurable disease and 2) We don’t always know what aspect of basic science and basic research will end up helping patients, but without it, we wouldn’t have identified the virus, developed life saving treatments, and, if the stars align and we can deploy lenacapravir, we may yet end the pandemic.

My journey through Covid was similar to that of so many ID docs. It was perhaps different in that I had been involved in studying pandemics and pandemic preparedness for 20 years when January of 202o arrived. So much of what I had counted on was proven wrong by 2022. I thought we could effectively explain what we didn’t know and how the response had to change as we learned more. I thought that ordinary folks and the media would understand that science changes as we learn. I believed that Americans were at their best in crisis, and the things that united us would prevail when most needed. I thought our leaders would put raw politics aside. I believed that the public, despite the personal suffering they endured, would look out for their neighbors, and respect and honor those who ran towards the fire, whether a bus driver, cop, nurse or ID doctor. They did at first, but now we are a divided and distrustful nation.

On the bright side, science and clinical trials were again successful in Covid, and years of basic science and investment allowed the development of mRNA vaccines in record time.

So many of the lessons of the two pandemics are lost on our current leaders. As Jeremy Faust and Craig Spencer discussed on Substack, the greatest is perhaps the loss of empathy as a guiding principal for our country.

Dr. Sax :

Thank you so much for this extremely well written piece that expresses such well informed compassion. As a family practice physician who had pursued medicine as a calling and context in which to share my faith, I was so disheartened to see people who shared my faith so easily fall prey to misinformed politicization and conspiracy theory. This was manifested when a nurse who was my patient declined the Covid vaccine because” Bill Gates computer cost $666.66” or so she had heard, demonstrating that indeed this was the “mark of the Beast “.

You say effective therapy arrived in 1996, but zidovudine was FDA approved and widely prescribed starting in 1987 originally at doses greater than or equal to 1 g/day. Was this dose effective or did it poison patients to death while you and other infectious disease specialists misperceived the patient’s cachexia and wasting into a skeleton to progressing HIV rather than bone marrow suppression from the indefinite prescription of a DNA-chain terminator every 4 hours for life in some cases for no other reason than someone’s blood tested positive for antibodies on tests now conceded by all to be nonspecific?