An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 30th, 2024

The Riveting Conclusion of How PCP Became PJP

Before I get back to the saga of Brave New Name — How PCP Became PJP and Why It Matters, allow me to share that I had some trepidation about publishing this thing.

A deep dive down a hole with very high-risk for tularemia exposure (see what I did there?), it veered off topic more than half-baked Tesla Robotaxi loses the roadway during a driving snowstorm. Worried, I tested a draft of Part 1 out on a regular reader I trusted very much. (Ok, ok, my Mom.) She confessed she was “skimming by the end”, which made me concerned I’d gone too far.

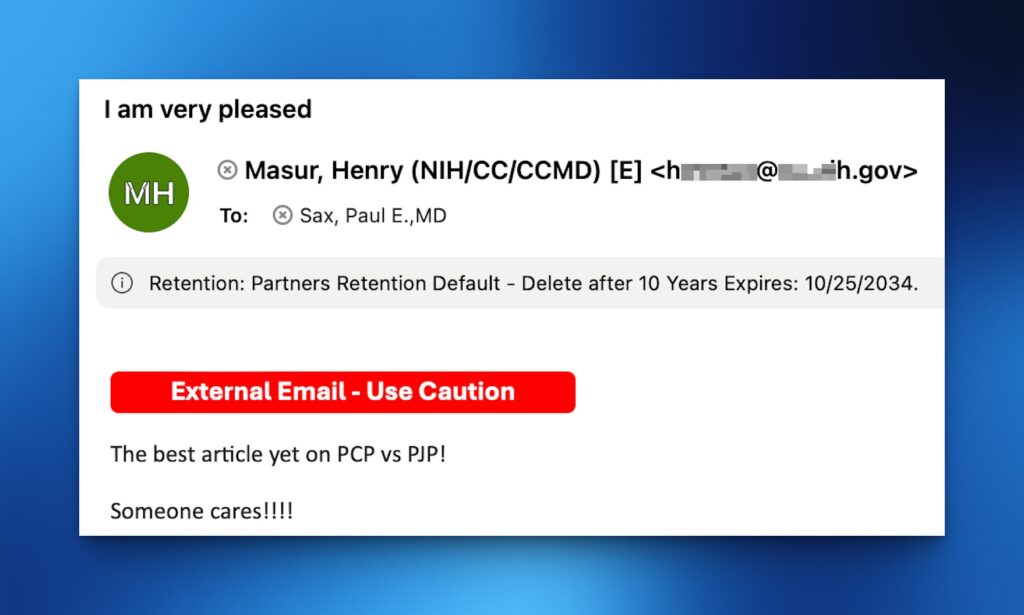

But when I got this after posting Part 1, I knew the piece had hit its target:

Kind email from Henry, shared with his permission.

Dr. Henry Masur! The Pneumocystis Expert Extraordinaire is “very pleased”! Amazing!

Now, back to our story.

(Read this next sentence like a voiceover starting the next episode in your favorite series … )

Previously, on Brave New Name — How PCP Became PJP and Why It Matters, we learned that the cause of the most famous HIV-related opportunistic infection — Pneumocystis carinii — was actually a rat fungus, and not a human pathogen after all. The name Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, and its abbreviation PCP, were both in jeopardy.

If we take the perspective of the scientists making the discoveries about the genetic basis of the organism, this was not a time for sentimentality — it was a time for facts. Pneumocystis carinii was not the bug infecting humans, and that error deserved correction.

To solve this problem, a group of motivated researchers gathered in 1999 at a meeting to settle the issue once and for all. (That meeting must have been a banger.) In a bold move strongly supported by the molecular evidence, they renamed the human pneumocystis Pneumocystis jiroveci (more details here without a paywall) in honor of the the Czech parasitologist Dr. Otto Jirovec who first described the infection in humans.

(Ostensibly the first. Read on.)

Shock waves resonated through the ID and microbiology community. I remember walking down the street in Back Bay, Boston, one July evening in 1999, enjoying some warm summer breezes, and suddenly I heard a loud screams in the distance. What had happened?

Pedro Martinez had struck out 5 of the 6 betters he faced in baseball’s All Star game at Fenway Park. It had nothing to do with this Pneumocystis name change. Still, this novel last name (jiroveci?) of human Pneumocystis caused an multifactorial crisis of international proportions. Among the problems, here are a quick half-dozen:

1. No one knew how to pronounce it. This confusion continues today.

Hey Julien! Thanks for taking the time to make this video. Good try (and lovely music!), but a brief search would have yielded the correct pronunciation, which is “yee row vet zee”. Say it again with me — yee row VET zee.

Of course now that you’ve learned it, we’ll share that some think it should be “VET-chee”, not “VET zee”. But this is hardly the only issue.

2. The original spelling ended with one “i,” when in fact it should be two — jirovecii, not jiroveci. The error arose out of a conflict between standards set by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (one “i” for a parasite) versus the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (two “i’s” for a fungus). And yes, someone published a letter on this topic. (Wow, talk about padding your CV.)

Now say it again with me — yee row VET zee aye. Or, if you prefer, yee row VET chee aye.

Brief aside: (Editor: Yeah sure.) How many International Codes of Nomenclature are there? Where do the committees making the decisions meet? Do they get swag (water bottles, T-shirts, fleeces) at their meetings? If so, I’d like someone to send me a backpack with an “International Code of Canine Nomenclature” logo, which I’m sure has a cute pup on it. Thank you.

3. Not everyone agreed the name should be changed. Dr. Walter T. Hughes (remember him? he’s the “Famed Pneumocystis Guru” from Part 1, the guy with the Cushingoid rats) strongly opposed the change, stating that good old Otto Jirovec was not even the first person to discover the pathogen in humans — that credit should go to Drs. Meer and Brug, with a paper they published a full decade before Jirovec, who must have stolen a page from Carini’s book to claim he was the first.

More importantly, “changing the name to Pneumocystis jiroveci [sic] will create confusion in clinical medicine where the name Pneumocystis carinii has served physicians and microbiologists well for over half a century.” So wrote Dr. Hughes, who no doubt would be surprised that we post here a picture of him as a 3-year-old on his family farm in Ohio.

Dr. Walter T. Hughes, 1933 — although he wasn’t a doctor quite yet.

4. Other joined in the battle to save carinii. A certain Dr. Francis Gigliotti later took up the fight with his own impassioned plea — one where he saw the name change as an unfortunate first step in a chaotic world of new and confusing names for Pneumocystis, each derived from their species-specific origins:

Because the overwhelming majority of “species” are currently “undiscovered” at this point, anyone can submit a new species name for any of the Pneumocystis organisms that infect each mammalian host that has not yet been specifically named. If individuals choose such an approach, what effect will this have on the desire to have an organized system to name Pneumocystis derived from monkeys, chimps, rabbits, dogs, horses, cows, or goats, for example?

What effect indeed! Imagine our frustration as we cared for immunosuppressed goats with pneumonia, desperately trying to remember the goat-specific name.

A baby goat, otherwise known as a kid. Male kids are bucklings, female kids doelings. Aren’t you glad you read this blog?

Instead of rashly changing Pneumocystis carinii to Pneumocystis jirovecii, Gigliotti proposed setting up a task force headed by an impartial scientific body, such as the National Institutes of Health. Another meeting! And such a fine use of our taxpayer dollars, to address this important issue!

5. Despite these protests, advocates for the name change would not back down. Drs. Melanie Cushion and James Stringer (he wrote the spelling-change letter) swiftly countered Drs. Hughes and Gigliotti, defending the name change with strong words of their own: “Dr. Gigliotti’s argument against species recognition was stretched beyond reasonableness when it included a defense of practices inconsistent with sound microbiology.” Them’s fighting words!

And if you doubt the authors’ credentials, Dr. Cushion and Dr. Peter Walzer wrote a whole book about Pneumocystis. Entitled Pneumocystis Pneumonia, it’s now in its 3rd Edition. Here’s one Amazon Review:

Big words about a small bug

I was scrolling through the internet, looking for some light reading, and came across this substantial tome — 2.42 pounds, no less! The title drew me in. I was a big fan of Pneumocystis Pneumonia, 2nd Edition, by the same authors, and was looking forward to the next revision. I was not disappointed. Drs. Walzer and Cushion have a breezy style that others might tend to dismiss as not up to the serious task of fully conveying the scientific importance of Pneumocystis pneumonia. But I think they strike just the right tone. I can’t wait for Pneumocystis Pneumonia, 4th Edition.

(I made that review up. Sort of. Modified with permission from the original author.)

To be fair, Pneumocystis Pneumonia, 3rd Edition, is not cheap (list price $170). But at over 700 pages long, the book arguably is excellent value. I have a copy on my coffee table.

6. If the name is to be changed — and, much to Dr. Hughes’s and Gigliotti’s dismay, it ultimately has changed — what should the abbreviation be? We arrive back, finally, to the topic of these two posts — you thought I’d never get there, didn’t you?

Even after Pneumocystis jirovecii’s widespread adoption, some wanted so badly to stick with PCP over PJP that they dug up a “c” in the middle of the new name that they could recycle: PneumoCystis jirovecii pneumonia. Clever!

Indeed, several change-the-name-to-jirovecii advocates, backed by the legendary Dr. Ann Wakefield (of Pneumocystis wakefieldiae fame), even embraced this compromise. Tossing a bone to the Pneumocystis carinii supporters, she wrote this reassuring sentence in the abstract of a paper, undoubtedly to assuage the complaints they probably didn’t anticipate would become so passionate.

Changing the organism’s name does not preclude the use of the acronym PCP because it can be read “Pneumocystis pneumonia.”

My friend Dr. Joel Gallant has always loved this solution, a way of harkening back to happier and more innocent times when Aggregatibacter aphrophilus was the much more mellifluous Haemophilus aphrophilus. As a result, for many years one of the chapters on Pneumocystis pneumonia I wrote in UpToDate included this sentence:

The abbreviation of “PCP” is still used in the infectious disease community to refer to the clinical entity of “PneumoCystis Pneumonia”; this allows for the retention of the familiar acronym amongst clinicians and maintains the accuracy of this abbreviation in older published papers.

Well, PCP would no longer technically be an acronym — it’s not the first letters of other words, the definition of an acronym — but it seemed like a reasonable compromise. Now everyone can be happy, right?

The Big Conclusion

Well, not happy for long. Time marches on, and with it the generation of doctors and nurses and pharmacists who clung to Pneumocystis carinii and PCP have gradually been outnumbered. Younger clinicians, less-biased by these historical squabbles and unaware of the gymnastics required to keep the abbreviation PCP relevant, simply don’t care. They see something called Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and turn to the most immediately obvious shortcut — PJP.

In other words, younger age is an independent predictor of use of PJP over PCP. I base this on a multivariable analysis the NEJM Journal Watch statistical editor did on the responses to my original poll, using the demographic information each participant provided. Although such an data review never occurred — no one submitted demographic information, and there was no multivariable analysis — it sounded so impressive to write that, I couldn’t resist. Nonetheless, the first sentence of this paragraph is still true. Younger folks pretty much all say PJP.

And in order to stay youthful, that’s what I call it now too. Look, here’s proof!

Have a great Halloween, everyone! And thanks for sticking around to the end.

So well written

Thoroughly enjoyable and of course informative

Thanks a ton

Let me know if you need a statistician to do your next multivariable analysis.

🙂

Great read!

Thank you for the two-parter and highlighting how change can be difficult!!! The bat species I did my Master’s Thesis on was, at the time, universally known and accepted as Myotis keenii septentrionalis (1991) even though a species split (Myotis keenii and Myotis septentrionalis) was officially put forth by van Zyll de Jong (1979, 1985) and Jones et al. (1992). Much debate, disagreements, and challenges occurred until Myotis septentrionalis was the final word by the American Society of Mammalogists in 2022 (and Myotis keenii morphed into Myotis evotis). I am sure there are many more taxonomic tales of terror for countless species and all with very interesting stories within their own demographic niches of study. (Please excuse the improper way of displaying the species names as I was unable to make the names italicized)

Paul

Thank you for your thoroughly enjoyable history and analysis of this gripping controversy. You mentioned me as one of the proponents of keeping “PCP” (to stand for PneumoCysitis Pneumonia). This solution not only preserves the familiar and historical acronym, but it also lessens the need to worry about how to spell and pronounce “jirovecii.” My opinion on the subject hasn’t changed, though I admit that we “remainers” have clearly lost the battle.

If it were almost any other acronym, I wouldn’t have such a strong opinion. I don’t quibble about “MAI” vs. “MAC,” for example, and if someone wanted to rename “VZV” it wouldn’t keep me up at night. But the term “PCP” has great historical significance. This is the disease that killed so many of our patients in the 1980’s and 90’s. More importantly, it’s a term our patients knew and used themselves. Those who feared this condition, and who often suffered or died from it, may not have known what it stood for, and they wouldn’t have cared whether it was a parasite or a fungus, but they sure knew what “PCP” was. Changing it now seems a little like retroactively renaming “AIDS” decades after the term had its greatest importance.

You’re right about the generational effect. The first time I heard the term “PJP” was at a Hopkins case conference when the term was used by a fellow. The attendings in the room shared puzzled looks but didn’t say anything–we wondered whether we’d missed the memo or, as is so often the case, were behind on changes in the lexicon that young people always seem to know about first. We should have spoken up, but it’s too late now.

I’ll close with a paragraph from the 2002 paper by Stringer and colleagues entitled “A new name (Pneumocystis jiroveci) for Pneumocystis from Humans”:

“Given the compelling evidence that the human form of Pneumocystis is a separate species, the most important objection to designating it as such has been the problem that this name change could create in the medical literature, where the disease caused by P. jiroveci is widely known as PCP. This problem can be avoided by taking the species name out of the disease name. Under this system, PCP would refer to PneumoCystis Pneumonia. This simple modification in the vernacular accommodates the name change pertaining to the Pneumocystis species that infects humans. Furthermore, adopting this change makes the acronym appropriate for describing the disease in every host species, none of which, except rats, is infected by P. carinii.”

Thanks for this detailed comment!

And Stringer strikes again! He penned the jiroveci –> jirovecii spelling-change paper.

-Paul

Good stuff! And thanks for trying to protect Dr. Masur’s privacy but as an FYI, it is on the NIH website 🙂

Yes, but why should this be the place people find it?

– Paul

Thanks for sharing! I really enjoyed the story – super interesting and informative.