An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 29th, 2010

With HIV Medication Adherence, It’s Not a Competition

There has been an irresistable urge for people — doctors, public health officers, politicians, journalists, the usual pundits — to compare adherence to HIV treatment in resource-rich vs. resource-limited setting.

There has been an irresistable urge for people — doctors, public health officers, politicians, journalists, the usual pundits — to compare adherence to HIV treatment in resource-rich vs. resource-limited setting.

I suspect this is because the whole issue got off to a famously bad start in 2001, when then-head of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Andrew Natsios said in an interview with the Boston Globe that Africans:

… don’t know what Western time is. You have to take these (AIDS) drugs a certain number of hours each day, or they don’t work. Many people in Africa have never seen a clock or a watch their entire lives. And if you say, one o’clock in the afternoon, they do not know what you are talking about. They know morning, they know noon, they know evening, they know the darkness at night.

Yikes.

The reality, of course, is that patients in Africa and other resource-limited settings have been just as adherent to HIV treatment as people in developed countries.

But are they more adherent?

Yes, says this article in the New York Times. And yes again, says this widely-quoted meta-analysis, published in JAMA in 2006.

But I don’t buy it — never have.

In fact, in his otherwise inspiring talks on how to bring lifesaving health care to poor countries, my doppelganger Paul Farmer has a small section I absolutely hate. (Am I allowed to criticize Paul Farmer? Sure — he knows it.) It’s where he compares adherence rates for Haitians in his community-based programs to that of patients discharged from the inpatient medical service at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta.

Not surprisingly, the Haitians do better. But that’s not really a fair comparison, because in Haiti the people on treatment are actively seeking care, while with these particular patients at Grady, they are actively running away from it until they get so sick they need to be hospitalized.

At the great risk of oversimplifying the issue — and acknowledging up front that I do my work exclusively here in the USA (but in a setting with a very broad range of patients) — here’s my take:

- Most people with HIV — everywhere — are phenomenally adherent to therapy. Not only that, it gets better over time. Excellent adherence is especially common in those who, as mentioned above, are seeking care rather than trying to evade it. Remember the AZT-every-4-hours group? The indinavir-every-8-hours-on-an-empty-stomach group? With today’s easier regimens, lots of patients barely ever skip a dose, and they look at you like you’re crazy when you ask them how often they miss. And Carlos del Rio tells me that many of them are receiving care right near Grady at the outstanding Ponce de Leon Center.

- It is incorrect to think that this ability to take medications differs in different countries. In the same way that Natsios got it wrong about Africa, it’s wrong to assume that we can’t do it here based on antiquated data, examination of only a selected subset of patients, or reverse cultural assumptions. I heard someone once say at a lecture that adherence was worse in the United States than in Kenya because US HIV patients “take everything for granted.” Yikes again.

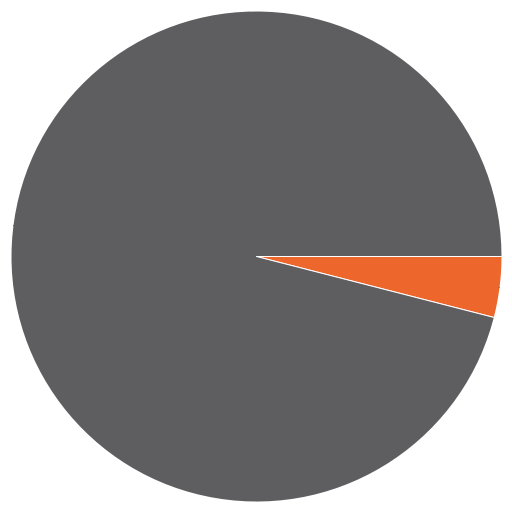

- The huge benefits of HIV therapy notwithstanding, some people just don’t get it, and they drive us crazy. Everyone knows a small group of patients — see pie graph above, as my unscientific estimate puts it at 5-15% — who just won’t play the ART game by the rules, or at least won’t do it consistently. They are in denial; or they don’t really believe you that HIV is lethal; or they have side effects to everything; or their life is in total chaos; or they have psychiatric illness; or they have drug or alcohol problems. Or all of the above. And you know what? Though small in number, such people are everywhere (even in Africa), and found with every disease. They occupy a tremendous amount of our clinical energies and a disproportionate share of resources — and not surprisingly, it’s this group that gets hospitalized repeatedly at Grady, as well as every other hospital that sees its fair share of HIV patients.

So the next time you hear someone make a broad generalization about adherence being better in City A vs B, or Country X vs Y, remind them that people are people — and adherence to HIV therapy is likely to be the same everywhere.

That is, excellent until proven otherwise.

Exactly. I work in 2 settings in South Africa. In the public sector patients have to queue and jump through a number of hoops to get HAART and we see excellent adherence rates. In the second, employees are tested every 6 months and treatment are freely available. Only complicated patients are referred to my care – they present with low CD4 counts, often refuse HAART, high rates of LTFU and poor adherence (“the nice patients have been skimmed off” and I never get to see them).

Superbly articulated. I work in an HIV clinic with a diverse population including patients from over a dozen developing countries as well as many from the US. Our cohort of patients who have great difficulty adherring to HAART represent all these countries as well as many more from the USA. These folks occupy most of my time as a social worker; “people are people’! Thanks for clearing up this misconception!