An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

April 1st, 2018

News Flash — The World Isn’t Sterile

You might have missed this press release from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID):

Bethesda, MD

April 1, 2018

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, at the National Institutes of Health, invites grant applications which propose research in the following 3 critical world health challenges:

1. Development of an effective HIV vaccine.

2. Global eradication of malaria.

3. Identification of the germs you can find lurking on or inside everyday objects. Priority items for this research include the kitchen drying rack, the shower curtain, and bathtub toys.

Well, not really.

But the inspiration for that (lame) April Fools’ Day joke was this recently published study finding bacteria inside your kid’s rubber duck.

And it’s not just rubber ducks. A prior study found these and other scary bugs in your office coffee maker.

While we’re at it, let’s take a look at your flight’s tray table.

On your kitchen sponge.

Or in the other room, on your TV remote control.

Outside, in the playground sandbox.

And beware your doctor’s necktie and stethoscope. And that white coat? Teeming. I could go on and on.

(In fact, I already did!)

Indeed, if you look hard enough, bacteria can be found literally everywhere — except perhaps inside your hospital’s autoclave.

What’s missing from all these studies, of course, is a correlation between identification of these bugs and any subsequent diseases. It’s not as if kids with rubber ducks are coming down with more infections than kids who don’t have them.

Perhaps a competing bath toy company will fund a clinical outcomes study, but don’t hold your breath. The rubber ducks have quite a stranglehold on this market.

In summary, bacteria on common household, work, and travel items are ubiquitous; furthermore, we lack any clinical data that this is important in any way.

Hence, I wonder — why are these “we found bacteria on [common-item]” studies so common? Even more perplexing, why are they such popular news fodder? The press can’t seem to get enough.

Hence, I wonder — why are these “we found bacteria on [common-item]” studies so common? Even more perplexing, why are they such popular news fodder? The press can’t seem to get enough.

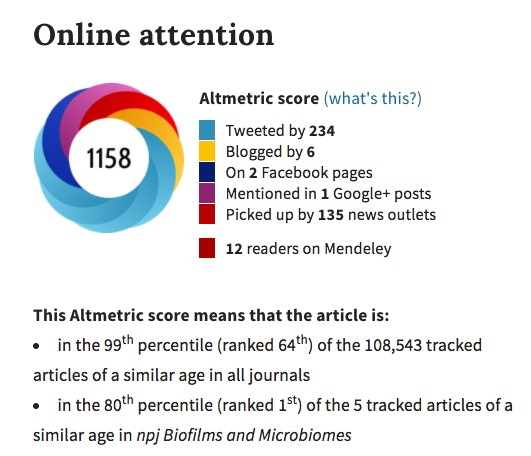

According to its Altmetric score (pictured to the right), the above-mentioned rubber duck study is a bigger news story than the fact that rates of tuberculosis in the USA have reached historic lows.

(Since TB control is one of the few things our crazy U.S. healthcare system does really well, I like to publicize these data whenever possible. You’re welcome.)

And what do we call these studies? Clearly the very category deserves a name:

I need a clever word or phrase to describe this category of study: "We cultured [common household/work/travel item]; here are the [scary sounding microbes] we found."

Suggestions? https://t.co/jSPg8LTi5n— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) April 1, 2018

While there are several excellent proposals, I’m particularly partial to two answers so far — “Quotidiome” and “Ubiquibiota” — and certainly understand the appeal of “Nocarediosis,” though that one might be a bit too obscure for non-ID types.

Any other ideas?

These stories drive me crazy, especially when they are reposted on social media by panicked people looking for something new to fret about. The first one I remember wasn’t about bacteria per se, but about all the icky things you could find on hotel bedspreads if you had the proper testing equipment. Did we REALLY need to know that, given that those bedspreads had presumably never made anyone sick? Ignorance is bliss!

Microcohabitosis?

That families survive the kitchen sponge has always amazed me.

Like Mimi Breed’s April 1, 2018, response to the above blog by Dr. Sax, MD! Also, the reply by Dr. Sax to the religious rituals was fascinating about low infection risk taking communion question.

I have always disliked sponges even before recognizing the science behind all the germs and bacteria that they harbor (moist, crevices that hide dirt and bacteria, etc, and harbor microbes on surfaces of kitchen floor, counter-tops, baths, etc.) Dislike to the point that even seeing one (hard, shriveled up and nasty, laying on the periphery of a sink or tub, made me physically nauseated. I cannot prove it but maybe that’s why they invented Swiffers; just toss away the dirt liner instead of leaving it in a sponge to multiply bacteria!

Also, the Brillo pads of yesteryear that moms used to clean pans and ovens freaked me out as a kid.

I know that the “hygiene hypothesis” tells us that we are seeing many more kids with allergies because of a lack of childhood exposure to dander, certain foods and molds. I am now intolerant to lactose, RICE, gluten, wheat and every other grain except buckwheat and you know what – your tongue may show different allergic reactions as well thanks to the fact that I am an Oriental Medicine practitioner and Acupuncturist.

Has anyone ever done a study about allergies related to how it shows up on the tongue during tongue diagnosis? We were taught that the tongue is a reflection of the internal organs – paired yin and yang. Liver/Gall Bladder, Heart/Small Intestine, Spleen/Stomach, Lung/Large Intestine, Kidney/Bladder, etc.

I am not an ID Dr, having read Hot Zone, Spillover, The Coming Plague, The Diease with No Cure, The Deadliest Enemy…. we live in and endless sea of biota, with a billion years of DNA, washing over us. It amazes me that we have survived at all. Thx to our symbiotic biomes….

Clean water and sewage along with immunizations has undoubtedly contributed more to improved public health than all the antibiotics combined. However, the pursuit of ultra-cleanliness may make us susceptible to other health issues. The “hygiene hypothesis” proposes that we are seeing many more children with allergies because of a lack of childhood exposure to dusts, dander, and certain foods. Maybe the Charles Schulz character, “Pigpen”, is healthier than we think,

Paul, here is a question I have had for years: from a microbiological or public health standpoint, should one “sip it or dip it” when it comes to taking communion. Let’s assume sipping is from a common cup. I’m a sipper. I can understand those who might think this is a bit gross, with perhaps a hundred folks taking a sip from the same chalice (wiped with a cloth between persons). However, I have also observed dippers going a little “too far” and touching the wine with their fingers in the intinction chalice as they dip their bread. I doubt the church would take kindly to comparing quantitative viral and bacterial cultures from the drinking and intinction cups! So what say you, o guru 🙂

Hi Jon,

Here’s a public health take – I first looked into this when we were dealing with a meningococcal outbreak and churches asked us about the risk from a common communion chalice. We ended up with a basic multi-barrier approach: the antibacterial effect of the wine and silver of the chalice, the mechanical removal of saliva by wiping the edge of the cup with a fresh fold of clean cloth between each sip, along with separate little plastic cups for any parishioner who might not have been feeling well, or who had sores of their lips or mouth, or who had trouble with saliva control.

Since then, Pellini and Edmond have kindly done a very nice review (Infections associated with religious rituals, Int J Infectious Diseases 2013) that discusses the low infection risk of taking communion from a common chalice.

We had a lot more concerns about saliva sharing by other routes, whether directly or via fomites, with the latter category including water bottles, straws, instrument mouthpieces, toothbrushes, mouth-guards, etc. etc.

Brilliant!

What about the nebulizers and the nasty smells from the residual water molecules and medicines that inhabit the tubes?

As the meningococcal outbreak I mentioned was being transmitted in the community and not in hospitals, we didn’t find medical nebulizer sharing going on. (I’m not saying that nobody ever did it, but it certainly wasn’t common-place and it wasn’t an exposure identified by our cases.) Sharing of cigarettes / joints / crack pipes / bongs got mentioned sometimes, but nebulizer sharing didn’t seem to be an issue.

However, shared or not, you’re quite right that nebulizers need proper cleaning – e.g., Device Cleaning and Infection Control in Aerosol Therapy in Respir Care 2015 – http://rc.rcjournal.com/content/respcare/60/6/917.full.pdf .

With regard to the tubing, patient instructions online seem to suggest that the tubing should stay dry, but if moisture does get in to the tubing, dry it out by running the compressor; e.g., https://justnebulizers.com/respiratory-blog/how-to-clean-your-nebulizer/#.Wseb6H9lCUk (“Remove the tubing and place it to the side for now – since the only thing passing through it is clean air, it does not need to be washed.”), https://intermountainhealthcare.org/ext/Dcmnt?ncid=521456272 (“If there is any moisture in the tubing, let the compressor run with only the tubing attached for 2 to 3 minutes. The warm air from the compressor will dry out the tubing.”). The Cleveland Clinic has similar advice ( https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/drugs/4254-home-nebulizer .)

. . . but I’m sure Dr. Sax knows way more about this than I do!

In answer to the question “why are they such popular news fodder?”, one must look at the media, broadcast news, internet news and print news, and their model for financial success. All sell advertising. They can charge more for their ads the greater their viewership, listenership or readership. What attracts these? Sensational reporting. The days of Walter Cronkite and trust in the media are long gone.

After those research results are revealed we cut to advertisements about some home sanitising product to combat all these dangerous germs…

Hom(e)-biota!

biotanoia

I have always favored the term “bacterchezia.” Like for when I get consulted for a rectal swab positive for E. coli.

This one is alarming!!! Mice too are colonized with bacteria. It’s actually a wonder that numbers weren’t higher given their penchant for coprophagia. I’m partial to ubiquitobiota.

https://consumer.healthday.com/infectious-disease-information-21/bacteria-960/the-poop-on-house-mice-they-carry-superbugs-733012.html