An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

May 15th, 2014

CDC Recommends Broader Use of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis — Can We Make It Happen?

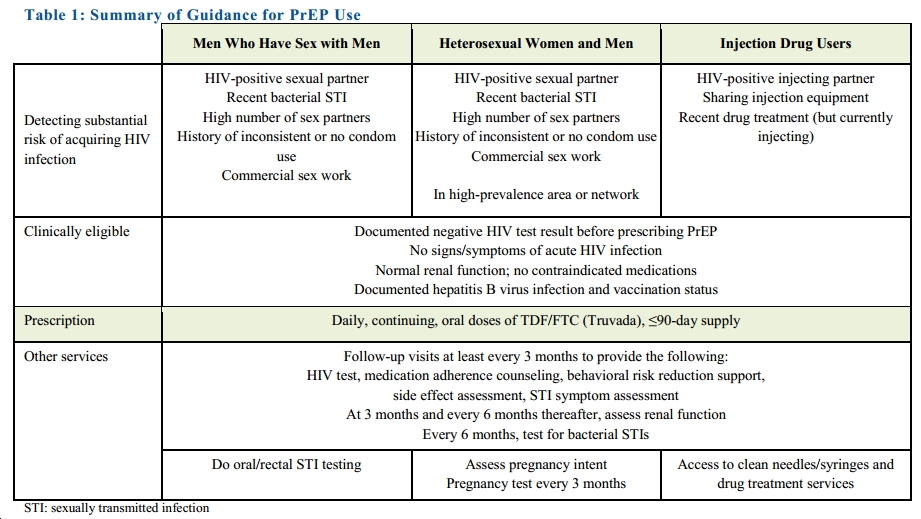

Making a much stronger and more comprehensive statement than their earlier “Guidance,” the CDC is now recommending tenofovir/FTC (Truvada) for all Americans at high risk for HIV. More specifically, they recommend it for a broad range of people who have certain risk factors (click to see full size image):

One certainly gets why this was done — as summarized nicely in this Times piece, it’s easy to be “frustrated that the number of H.I.V. infections in the United States has barely changed in a decade, stubbornly holding at 50,000 a year, despite 30 years of official advice to rely on condoms to block transmission.”

Plus, we know that PrEP really does work, provided people take it. An encouraging report from CROI this year found that adherence was nearly 80% among MSM seeking PrEP in three U.S. cities (Miami; Washington, DC; San Francisco).

And I have been surprised that we haven’t yet seen much of a decline in HIV incidence, even with a broader number of our patients in care receiving suppressive antiretroviral therapy, which essentially eliminates the risk of transmission to others.

However, it’s clear that the epidemic is being sustained by those not in care, which is why PrEP is so important. It also raises the first of several major challenges for clinicians, as the highest rate of HIV in the USA right now is in a population that tends not to access care on a regular basis — young, African-American MSM.

Other challenges:

- The risk assessment will have to be done on the front lines of care — that is, by primary care clinicians — as HIV-negative, at-risk patients do not see HIV/ID specialists.

- These PCPs will have to get comfortable prescribing tenofovir/FTC. It’s not that it’s complicated (“take one pill daily”), it’s just that it’s not a medication they currently use.

- They will also be responsible for monitoring both adverse events and (very importantly), incident HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Because of these issues, in the few years since PrEP became an option for HIV prevention, we’ve been offering our PCPs a one-time ID consult to discuss the risks and benefits, with a strategy for further follow-up outlined for the primary provider.

So can PrEP be more broadly adopted? I think we (meaning the patchwork U.S. healthcare system) can pull this off.

But it won’t be easy.

The recent guidelines of CDC on pre-exposure prophylaxis need to specify the criteria for high prevalence area and network, else it is based on subjective assessment which may not be applicable everywhere. There is a need to clarify specially for heterosexual men and women, whether staying alone in the high prevalence area without exposure can be considered for pre-exposure prophylaxis. Secondly, pre-exposure prophylaxis solely on the presence of bacterial STI would overburden the health care system in terms of provision of medicines and manpower which may not be feasible in resource poor countries. There is a need to relook into this aspect.