An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 21st, 2019

AIDS Conference Returns to Mexico City, Where We Saw an Underrated, Great Advance in HIV Therapy

If you’ve been an ID or HIV specialist for only a decade or so, the following statement might seem unfathomable to you:

Until 2008, there were lots of people with HIV whose medication adherence was perfect — but they still had virologic failure.

How could that be? The simple answer is that their virus had too much resistance to the then-available drugs.

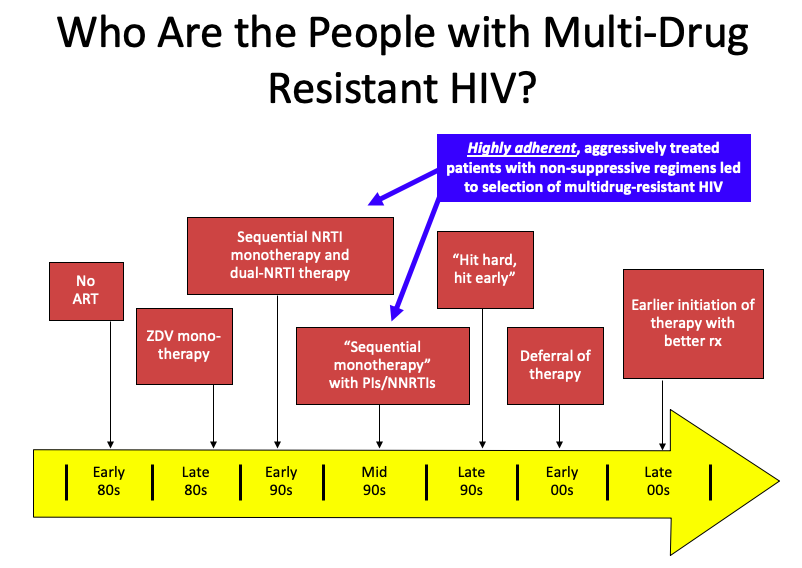

But it’s a bit more complex than that. Several factors converged, summarized in this PowerPoint slide:

(I once upon a time thought this slide originated with Steve Deeks — but now he denies creating it, so I’ll take “credit”. Hey, good slides are like recipes, incrementally adapted until they become your own. If the originator wants to come forward, I’m happy to add your name to the slide.)

It’s those people in the blue box that have the most extreme multi-class HIV drug resistance. Treated in the early-1990s with single or dual nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), they already had NRTI resistance when the protease inhibitors (PIs) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) because available in the mid-1990s.

Addition of a single active drug from these classes, often of marginal potency (nevirapine, delavirdine), or suboptimal pharmacokinetics (saquinavir, nelfinavir), or toxicity (ritonavir) acted as “sequential monotherapy”.

What we know now is that if they didn’t also add lamivudine as a new drug (which was still very active against most NRTI-resistant virus at the time), they were likely to experience treatment failure, with resistance to yet another drug class.

It didn’t help that we didn’t fully understand within-class resistance — for example, it was believed that the resistance profiles of zidovudine and stavudine were sufficiently different to transition a patient from one of these drugs to the other. Ditto certain nevirapine mutations and efavirenz. Not true!

The fact that our treatments failed in some of our most devoted and adherent patients resonated strongly with us HIV specialists. It was heartbreaking. Some had been hopeful volunteers in early clinical trials, which exposed them to inadequately dosed single-drugs that then led to a loss of this drug class. In hindsight, how ironic — and how tragic.

Others had to go through desperate (but ultimately failed) attempts to achieve viral suppression, including:

- “Mega-HAART” — using 6 or more drugs in untested combinations.

- “Double-boosted PIs” — two protease inhibitors with ritonavir.

- Hydroxyurea — raised intracellular concentrations of didanosine, with many untoward effects. Ugh, even writing that we prescribed that combination makes me cringe.

- Treatment interruptions in order to “resensitize” their virus to the drugs we did have — didn’t work, led to increased risk of disease progression.

The silver lining to this resistance was that the virus became less fit; the viral load rebounded, but there was a substantial delay before the CD4 cell count declined. Patients remained remarkably stable clinically even with viremia and resistance.

This disconnect between viral load rebound and CD4 decline allowed many to survive until the miracle year of 2008, when finally we had a potent new drug in a new drug class — raltegravir, the first integrase inhibitor, approved in 2007 — plus drugs from existing classes with activity against most resistant viruses, specifically darunavir (PI, approved in 2006) and etravirine (NNRTI, approved in 2008). (Maraviroc played a less important role, since most of these patients already had non-R5 virus.)

Why bring this up now? On the eve of the 2019 International AIDS Conference, which takes place this week in Mexico City, I think back to when the conference was here last — that magic year of 2008.

It was during that 2008 Mexico City meeting that we first saw data from the TRIO study (later published here, lead by Yazdan Yazdanpanah), which enrolled participants with resistance to NRTIs, NNRTIs, and PIs, and gave them all three of these new drugs — raltegravir, darunavir, and etravirine.

The results were staggeringly good — 91% had viral suppression at week 24, a rate quite comparable to responses in treatment-naive patients with no resistance. It was actually a bit better, reflecting the high level of adherence for these motivated participants. In HIV clinics around the world, this “TRIO” regimen became the default standard for treating multidrug-resistant HIV — and it worked just as well in clinical practice as it did in the clinical trial.

At last, we could effectively treat these brave people who had weathered years of viral failure, immunosuppression, and the toxicities of early antiretroviral therapy. Many experienced the joys of hearing they had an undetectable viral load for the very first time. Treatment failure with multi-class resistance became increasingly rare — so much so that a popular HIV drug resistance test stopped selling its product, the laboratory equivalent of closing an inpatient hospice for people with AIDS.

I’m happy to report that this wasn’t a brief honeymoon phase — responses were durable, and most people with multidrug-resistant HIV have had viral suppression since 2008. The reality is that in many parts of the world, the patient with “no treatment options” due to resistance has become an exceedingly rare occurrence.

Even busy practices and referral centers see very few of these cases; in the past two years, most have seen zero:

Hey HIV treaters out there–in the past 2 years, do you follow, or have you seen, any people with viral failure and resistance to ALL major HIV drug classes? (Enfuvirtide and ibalizumab excluded.) If yes, share how many in the replies. (I've seen 2.)

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 20, 2019

This is not to say that it never happens anymore — a paper published recently in Clinical Infectious Diseases enrolled 20 such individuals, admitting them to an NIH inpatient center for directly-observed therapy. Of note, in this group (which included several with perinatal HIV), nonadherence turned out to be the primary reason for failure in 9 of the 20.

So here’s to 2008, a year when our knottiest HIV-resistance problems became solvable — hooray! It was a tremendous advance, one underrated in my opinion when people retell the history of antiretroviral therapy.

And what we will learn this year in Mexico City? That will be next week’s post!

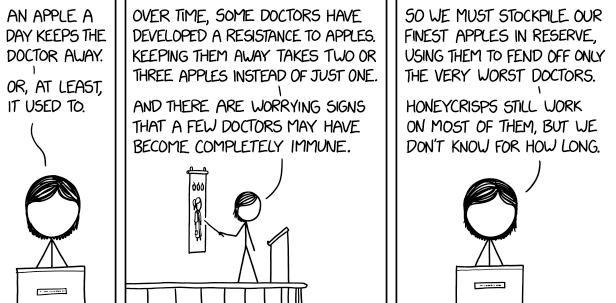

Speaking of drug resistance, here’s another take:

I love this and had not made the connection, but can confirm it as a result of having gone through all of my patients’ ART treatment histories and known resistance mutations in the process of retiring from clinical care and passing them along to my colleagues with what I hope will be everything they need to know. I am just in my teaching and sidelines-commenting roles now, not to mention Grandma duty. Sarah