February 6th, 2020

I’m Graduating from Residency! What’s Next?

Prarthna Bhardwaj, MD

My whole life, I have always wanted to do something that will be remembered. Becoming a physician was a hard but well-thought-out choice. Toward the end of my residency, I knew I wanted to be a hematologist-oncologist, but I had no idea what type of career pathway I wanted to pursue. During the APDIM Chief Resident Annual Meeting last year, I had the opportunity to attend a session on different career paths by Dr. Gregory Kane, Chair of Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. To make a long story short, my life changed for the better in a lot of ways after that session. In this post, I’ll attempt to lay out some pearls I took away from that session. In addition, there are snippets of my own research on a few topics.

Irrespective of what one does — be it primary care, hospital medicine, or sub-specialty training — one can pursue different paths.

Being a Clinician – Educator

In medicine, “clinician–educator” refers to a physician whose primary role is caring for patients and who has formally incorporated educational principles and scholarship into her/his job description.

In medicine, “clinician–educator” refers to a physician whose primary role is caring for patients and who has formally incorporated educational principles and scholarship into her/his job description.

In other words, these physicians usually stay on as faculty in programs that have a medical school, a residency program, or a fellowship program. They often function as your preceptor attending in the clinic or hospital setting. Their main roles involve patient care and educating medical trainees.

What kind of roles could I pursue as a clinician educator?

- Join a practice as an academic attending in the setting of your choice.

- Become a faculty member, like an assistant/associate professor or professor.

- Be a clerkship director for medical students.

- Develop curricula for trainees at all levels.

- Become an Associate Program Director or Program Director of a residency or fellowship program.

How can I hone my skills to be a Clinician-Educator?

- Some residency programs have a Medical Education Track. This is a great steppingstone to understanding the core concepts of Medical Education Training. Enroll for it!

- Journals, such as the Journal of Graduate Medical Education, and the MedEd Portal are great bonus resources. Most of these resources are available with free access through your institution.

- There are specific courses that you can pursue, including:

- Master’s in Medical Education: For example, Johns Hopkins University has a distance learning program. Be sure to keep your clinical schedule in mind when choosing a distance-learning course.

- Harvard Macy Program: Read my co-blogger Frances Ue’s post Reflections of an Aspiring Clinician-Educator for more information.

A Career as a Clinician-Scientist

Nearly everyone who pursues a career in medicine has the goal of improving patients’ lives. However, methods for doing that can take on different forms. Midway through residency, some residents realize that they want to spend most of their time doing research. If you are not an MD/PhD student but you want to be a researcher, you can still do it after residency! If bench research is not for you, there are plenty of opportunities for clinical research, including epidemiological research and clinical trials.

How can I hone my skills to be a researcher?

- Several large residency programs have a clinician-scientist pathway through ABIM. This is for medical students who know early on that they are interested in research. Several, if not all, programs require some background in basic or clinical research before enrollment.

- Take on extra courses to improve your understanding of research. This is a great way to start if you had minimal exposure to research during residency. These include:

- Master of Science in Clinical Research: Some programs provide tuition aid if you pursue these additional courses during residency/fellowship. Hence, these degrees can be pursued in-house, if there is availability. If not, several online programs are available.

- Master of Public Health (Epidemiology/Biostatistics focus)

- There are additional workshops available to hone your research skills. For instance, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) have combined efforts to conduct a workshop on how to design clinical trials effectively. This workshop happens annually and is available for Hematology/Oncology trainees and early-career physicians.

- Consider applying for a research fellowship after residency.

Pursuing Physician Advocacy and Public Policy

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world; indeed, that’s the only thing that ever has.”- Margaret Mead

As physicians, we often find ourselves at the crossroads of a unique and sometimes intimate knowledge of patient needs. This subsequently intersects with the ability to leverage influence to change healthcare system delivery, lower social barriers, and even impact political policy. We are in a unique position to advocate for patients in their times of vulnerability. Advocacy can happen at different levels — community level, state level, federal level and national level. All of this can result in policy changes.

How can I hone my skills to be a physician advocate?

- Several professional organizations at the state and national level have Advocacy and Health Policy committees. The members of these committees are instrumental in writing resolutions which are then proposed to legislators. There are dedicated times and opportunities to meet with legislators to lobby for your proposals. Some examples of organizations include the American Medical Association, the American College of Physicians, and individual state medical societies like the Massachusetts Medical Society. A great way to start is by joining your state chapter and finding out what work is happening at the grassroots level.

- There are courses available, like a Master’s in Public Health (with focus on Health Policy)

- Consider fellowship programs like the IMAP Physician Advocacy Fellowship, which seeks to make advocacy a core professional value for physicians.

Read further: Physicians as Public Advocates: Setting Achievable Goals for Every Physician

What Is a Physician-Administrator?

Given the rapidly changing healthcare environment, the need for effective healthcare leaders has never been greater. As a result, many organizations are recognizing that physicians are an asset as leaders of healthcare organizations. Their hands-on involvement in healthcare puts them in a unique position to translate their insights into successful healthcare management. Administrative Medicine” is a good fit for those who have insight into the doctor-patient relationship (the core product of healthcare) and an ability to think about operations globally.

What roles can I pursue as a Physician-Administrator?

- Physicians with administrative inclinations can become Chair of Medicine at their institutions.

- Chief Executive Officer and Chief Medical Officer of a hospital are career goals if you are looking to be an executive.

- You can become a Residency/Fellowship Program Director if you are interested in an administrative role and want to continue being a clinician.

- Medical Directors are administrators with specific spheres of influence.

How can I hone my skills to be a Physician-Administrator?

- Apply for a Chief Resident position if you think you might be interested but are unsure what to expect. This job gives a great first glimpse at what being in administration involves.

- Be sure to apply for any roles that would provide you with substantial leadership experience.

- Course options to help you hone your managerial skills include:

- Master’s in Business Administration, Master’s in Healthcare Administration

- American College of Physician Executives (ACPE) offers several leadership and management courses for physicians, including online courses.

Read Further: Becoming a Physician Executive: Where to Look Before Making the Leap

Practicing Clinical Medicine

Many physicians very clearly know that their sole purpose for going into medicine is patient care. Therefore, they choose to focus only on clinical medicine. A vast majority of them practice in private or group settings in the community. They spend 100% of their time seeing and caring for patients.

What kind of roles involve purely clinical practice?

- Non-academic hospital medicine

- Community primary care physicians or sub-specialists working for a hospital/group that is not attached to a training program

- Private practice

This is by no means an exhaustive list of options, but is meant to be a guide for your career pathway. Plenty of physicians choose to pursue alternative careers like medical insurance, pharmaceutical company position, or medical writing. Also, physicians who stay in academia often do a combination of the above during their careers. A simple Google search will yield plenty of results.

In conclusion, there are a bucketful of career paths to choose from after you graduate. Meanwhile, my bestadvice to you would be to seek out mentors in the field(s) you want to pursue. Nobody can steer your career the way a great mentor can!

*Resources available on this blog post are not endorsements in any way. No conflict of interest to disclose.

January 31st, 2020

Sorry, We’re Transitioning

Allison Latimore, MD

Dr. Latimore is the Education Chief Resident at the MedStar Washington Hospital Family Residency Program in Washington, DC

“We are transitioning.” In July of my intern year, this was the sentence that the CEO of our community hospital used to tell the staff that the hospital was closing its inpatient services. The emotions that traversed my mind were quite vast, to say the least. Anger was undeniably at the top of the list, but mostly directed at myself.

Initially, I thought medical school definitely did not prepare me for this. But it actually might have. While I was in medical school, our affiliated hospital was always in debt, and there was always talk about potential closure of inpatient services and labor and delivery, but nothing ever happened. Following the closure news in my residency program, I constantly questioned myself. How could I have not seen this coming? How could I have been so naïve? I saw what was happening at my own alma mater. What I did not see was that hospitals are closing all over the country.

Why are hospitals closing?

The answer seems very simple. Money. In the past decade, rural hospitals have been closing at an alarming rate, but this issue does not just affect rural areas. Hahnemann Hospital, in Philadelphia, had debt and losses of about $3 million to $5 million per month. Many hospitals that closed in 2019 cited decreased patient volume and decreased reimbursement as reasons behind their closures. The company that owned my community hospital planned on making investments in services such as telehealth, care coordination, home care, and community-based behavioral healthcare. But where does that leave the residents and the patients?

What can residents do to prepare?

My biggest piece of advice to every residency applicant is to research your employer. Many medical students are novices when it comes to joining the workforce. Being a resident was my first “real” job. I never thought to google the hospital that I was going to be employed by. If I had, I would have seen articles about potential closure, before the news was delivered by the CEO. I am not sure whether knowing this information would have changed my decision, but making an informed decision is much better than being blindsided.

I’m sure the displaced residents from Hahnemann Hospital would agree. I was very fortunate to be in a program that landed on its feet, and our residents were not “orphaned.” As a medical student, I had never heard the term “orphan” residents and couldn’t fathom starting a residency program and not finishing at that program.

I cannot imagine the immense stress of being an intern, having to continue to work at a place with impending doom, being on the hunt for an open spot, and setting up interviews all at the same time. Unfortunately, this is a possibility every medical student and resident should know about. We should be trained to review contracts prior to the match process. We should have a clear understanding that our programs could close, and we should know what the next steps are. Being a doctor seems like a very secure job, but your training could be compromised by hospital closures — perhaps we should not feel so secure.

How will this affect medical education in the future?

Safety net hospitals are the cornerstone of medical education. Many residents and medical students learn primarily in these hospitals. It teaches us compassion for the underserved and how to make a difference with limited resources. If there are no community hospitals left, who is going to train physicians to work with underserved populations, and where will these patients go? Surrounding hospitals try to pick up the pieces and accommodate the patients and the learners. But does that lead to oversaturated learning environments and less quality of care for the patient? How can our healthcare system create a safe space for patients and learners? Exposure to community medicine is one way to create physicians who are culturally sensitive and willing to return to underserved care. Without community hospitals, I am not so sure what the future of medicine will look like.

January 22nd, 2020

The ACGME Needs to Mandate Parental Leave

Eric Bressman, MD

Dr. Bressman is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, NY

My wife and I had a baby a few months ago. Or, more accurately, she birthed a child while I sat in the corner contemplating the miracle of reproductive physiology in a vasovagal fugue. In the months leading up to and following that wondrous moment, we found ourselves navigating the labyrinthine complexity of parental leave in graduate medical education.

To start with the positive, we are both residents in the same program and felt nothing but support from our own administration. We had advocates who helped us get an optimal amount of leave under the constraints of what the ACGME will allow.

But therein lies the problem. The ACGME and the various specialty boards (under the umbrella of the ABMS) are particularly restrictive when it comes to the amount of time off a resident can take in a given year and are largely silent on the topic of parental leave. This leaves the door open for wide variation in policies across institutions (e.g., Pediatrics 2013; 131:387 and Plast Reconstr Surg 2017; 139:245).

The Basics

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) is a federal law that allows eligible employees to take 12 weeks of unpaid leave after having or adopting a child. Eligibility includes having worked for the employer for at least 12 months, which means that interns are not covered. A handful of states have expanded on FMLA and mandate a certain amount of paid leave.

The ACGME requires that institutions provide written information about the hospital’s parental leave policy on the day of the interview and as part of the residency contract, and that this policy be compliant with local laws. That’s it.

At the same time, specialty boards set limits on the amount of time off residents can take in a given year, generally on the order of 4 to 5 weeks, inclusive of vacation time. Program directors can retroactively petition for a limited extension of this leave if they feel the resident has achieved necessary competencies despite the additional absence.

This all amounts to something pretty far from a parental leave policy, and instead results in a whole lot of confusion as to what residents are actually allowed to do (JAMA 2018; 320:2372).

The Imperative

There are clear parallels between the issue of parental leave and the limits on resident duty hours. While the Bell Commission grew out of patient safety concerns, the subsequent duty hour reforms eventually were viewed through the lens of resident wellness. Parental leave needs to be considered in light of both of these concerns, with the added consideration of infant health and wellbeing. New mothers endure the physical toll of pregnancy, labor, and recovery, and both parents suffer from chronic sleep deprivation on par with any 24-hour call. To assume that these factors don’t impact clinical performance is at best naïve and at worst negligent.

The associated stress is a tremendous driver of burnout, which disproportionately affects women in medicine. Nearly 40% of surgical trainees, for example, reported that they considered leaving residency during or after pregnancy for a host of reasons, including dissatisfaction with leave options (JAMA Surg 2018; 153:644). Many women simply choose to postpone childbearing until after their training years, largely driven by perceived threats to their career paths (Acad Med 2010; 85:640). When women do become pregnant during residency, they can experience higher rates of certain pregnancy complications (Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102:948), including pre-eclampsia, preterm labor, and fetal growth restriction (N Engl J Med 1990; 323:1040).

On top of all of this, there are concerns for fetal and infant wellbeing. As physicians, we are taught the importance of parent-child bonding in the first months of life, but the combination of limited leave and long work hours leaves little room for this among our own trainees.

Solutions

For starters, the ACGME should mandate a minimum amount of guaranteed parental leave, plain and simple. As noted, the void left by not having a policy begets confusion and, in some cases, allows for dangerous working conditions.

There are two common counterarguments to legislating guaranteed leave:

- The first is the impact on training, and progress toward independent practice. Anyone who has hit the interview trail knows there is reasonable variation in how residents spend their time at different institutions. Not every rotation is handpicked for its singular educational value, and that’s OK. We are both learners and employees. Instead of blindly setting limits on time away, the ACGME and specialty boards should set specific target exposures and milestones. As long as these are attained, leave should not impede someone’s progress through training.

- The second counterargument pertains to the unfair burden placed on co-residents. Residency scheduling is a zero-sum game; one person’s leave is another person’s call. The solution is either to employ physician extenders who can fill gaps or offer overtime pay to residents who are called on to do extra work. The former was done de facto when duty hour restrictions were implemented, and the latter would, for many, turn an undue burden into a welcome opportunity.

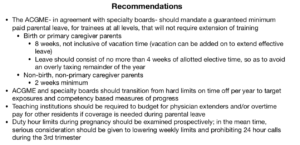

Many more arguments, pro and con, can be parsed out here, but I will leave these for another time, and instead will summarize a few recommendations, some of which are my own, others of which have been suggested elsewhere (J Grad Med Educ 2019; 11:362; click the image below).

Conclusion

The US lags behind many other countries in providing benefits for new parents. The medical community has penned multiple position papers calling on congress to rectify this disparity (e.g., ACP: Ann Intern Med 2018; 168:874). Legislative action may be beyond our control, but at the very least, we can lead by example. It’s time we get our own house in order, and there’s no better place to start than the most vulnerable among us.

January 16th, 2020

Reflections of an Aspiring Clinician-Educator

Frances Ue, MD, MPH

Recently, I had the pleasure of hiking up Roys Peak in South Island, New Zealand. A challenging 1586-meter summit that offered magnificent views of Lake Wanaka and snow-capped mountains of the Southern Alps. On this hike, devoid of phone calls and pages, I reflected on my journey as an aspiring clinician-educator. Many of us (like my fellow blogger Prarthna in Why Did I Spend an Extra Year as a Chief Resident?) want to teach, become better at this skill, and have a career that supports this goal.

So, how do we create careers as clinician-educators (with a big E)?

Feeling exhilarated to be at the peak! Roys Peak in South Island, New Zealand

In medicine, the clinician-educator term refers to, “a physician whose primary role is caring for patients and who has formally incorporated educational principles and scholarship into her/ his job description.” These physicians distinguish themselves from other clinicians by, “using evidence-based educational constructs to teach around patient illness and wellness, and converting those constructions and innovations into scholarship.” (Acad Med 2018; 98: 1764)

Harvard Macy Institute’s program for postgraduate trainees is one way to gain theoretical and practical skills towards a clinician-educator career. I had the privilege of attending last month. This three-day intensive program is paired with a year-long scholarly project in medical education and serves as an entry into the Harvard Macy community. I walked away from the course feeling excited and inspired. I’d like to share some highlights of what I learned from the course and about myself.

What I learned from the course

- How to turn innovative ideas into scholarship

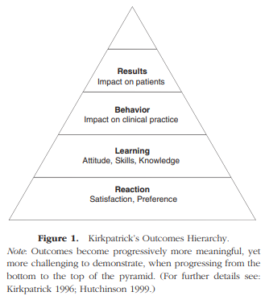

Beckman and Cook (Med Teach 2007; 29:210) is a must-read for anyone interested in medical education! These authors describe a three-step approach to designing scholarly education projects grounded in the theoretical basis of Boyer and Glassick: 1. Refine the study question, 2. Identify design and methods, and 3. Outcomes. In particular, Kirkpatrick’s outcomes hierarchy has been invaluable in developing targeted outcomes.

- Practical tips for advancing my scholarly project

I am forever grateful to my project group with mentors Alan Leichtner and Arielle Langer, and members Yakira, Christina, and Larissa. Not only were we a powerhouse team of #WomeninMedicine (and Alan), but we shared thoughtful feedback on each of our projects and practical tips for success. Arielle would often emphasize celebrating the small wins; an embrace of the small advances of our work.

- Ways to seek training in medical education

In addition to training at the Harvard Macy Institute, we discussed ways to seek out educator development opportunities at our own institutions (for example, a medical education residency track). Coursework is also available at the Preceptor Education Program for Health Professionals and Students. And lastly, fellowship training in medical education also exists at Stanford and Rabkin/Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

What I learned about myself

- How I learn and teach

I learned that I have an accommodating learning style (a combination of concrete experience and active experimentation; Kolb learning style inventory) and an apprenticeship perspective on teaching (Teaching Perspectives Inventory).

- The joy of micro-teaching

I taught a micro-teaching session on ‘how to run a marathon’ with my group members pretending to be runners. It was an energizing exercise that included the teaching segment being recorded and then viewed by me for self-reflection and by the group for feedback. I learned that my bubbly energy becomes much more magnified with enthusiastic learners.

In addition to the highlights noted above, I think what makes the Harvard Macy Institute so special are the people; the community of scholars and faculty who share boundless passion for medical education. Sometimes the journey toward becoming a clinician-educator can feel like scaling a 1586-meter summit. But with the guidance and mentorship of my Harvard Macy community, I know we will all reach the peak together.

In addition to the highlights noted above, I think what makes the Harvard Macy Institute so special are the people; the community of scholars and faculty who share boundless passion for medical education. Sometimes the journey toward becoming a clinician-educator can feel like scaling a 1586-meter summit. But with the guidance and mentorship of my Harvard Macy community, I know we will all reach the peak together.

I would love to hear from trainees and faculty passionate about medical education! Feel free to post a comment below or tweet at me UeFrances.

December 19th, 2019

Yogurt – The Cure to Resident Burnout

Daniel Orlovich, MD, PharmD

What is the latest answer to resident burnout? It may surprise you.

Recent research from a large Midwest academic center suggests that not one but two dollops of yogurt may help stymie resident burnout. “When we first started to look at the reasons why so many residents were burned out, we couldn’t understand it,” stated the associate program director, “so we started a dig a little bit.” This digging, of course, did not involve actually asking those most affected by resident burnout — residents themselves.

So, to address that gap, here are some thoughts from actual residents:

- One intern referenced the financial strain felt by some. “I mean, average debt has gone up 270% from 1986 to 2018.” (Acad Med 2011; 86:840 and AAMC.org student debt)

- Another brought up the pace of the current healthcare system. “In 1972, the average length of stay was about 14 days — in 2009, it was 4.8 days (JAMA 1990; 264:1984). And residents in 1972 and in 2009 took care of the same amount of patients, too” (J Health Soc Behav 2012; 53:344).

- Another senior, while clicking on the computer, stated plainly, “the average ER physician clicks more than 4000 times per day and spends 44% of his or her day doing data entry (Am J Emerg Med 2013; 31:1591). And another study showed that IM residents spend as much as five times the amount of time documenting care as providing direct patient care” (Ann Intern Med 2017; 166:579).

- A current PGY3 thinks the solution is probably more nuanced: “Where is the right balance between educational versus service requirements? How about the right amount of supervision versus autonomy? These aren’t such a black and white issues, I suppose. I’m not saying residency is harder than it used to be — it is just different, that’s all.”

None of these facts were considered for the study.

“Residents now have the 80-hour cap. That means they work less than residents did before. So, there shouldn’t be any burnout. Burnout is all about hours worked,” stated the associate program director, noting how all professionals work hard early in training.

Yet, compared with other college graduates, residents are 1.6x more likely to be burned out, and 2x more likely to feel depersonalized, and they score lower on mental, physical, and emotional markers for quality of life (Acad Med 2014; 89:443).

Without seeking to understand or pinpoint the root cause of the burnout, and after residents fell asleep during the lecture on sleep hygiene, a one-size-fits-all approach was proposed — yogurt.

The program started to incorporate a mandatory dollop of yogurt during wellness lectures. This allowed the program to check off the box for “wellness” activities. Serendipity, the bedrock of all discoveries, occurred: as a medical student entered into this wellness lecture hoping to eat the free food, he ended up receiving not one but two dollops of yogurt.

“And when I saw the medical student’s face when he received two dollops of yogurt, I knew we were on to something,” said the associate program director. “Without any resident input at all, we then started a ‘two-dollop’ lecture. This was followed by a mandatory yogurt training module. Then, we worked with IT to create a checkbox to be clicked in the EMR to show that training was complete.”

Since those changes have been made, the following lectures were Band-Aids. Not in the figurative sense — actual Band-Aids were given out. Of course.

Author’s note:

This is satire. Of course, residency has become more humane. To have the opportunity to serve as a physician is an incredible privilege and special honor. Of course, it takes many hours to learn how to be an excellent physician. However, it doesn’t have to be any harder.

The question isn’t whether wellness lectures work. The issue is how they are done. Presenters sometimes miss the mark when they hand down mandated solutions, refuse to seek resident input, and fail to show an interest in understanding and acknowledging the current training environment. When done right, though, they can confer admirable and positive results. That means seeking out resident-led initiatives, being flexible in when they are performed, and addressing concerns that speak to residents.

December 12th, 2019

Why Did I Spend an Extra Year as a Chief Resident?

Prarthna Bhardwaj, MD

Dr. Bhardwaj is an Internal Medicine Chief Resident at UMMS – Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, MA

I was in conversation with a residency applicant recently when we broached the topic of my career plans. I explained that I was interested in pursuing a hematology/oncology fellowship in the future. He asked “Why did you do a chief year, then? Were you trying to improve your application?” At first, I was somewhat offended, but I quickly recollected the number of times I have been asked why I chose to do a chief year. For folks who are genuinely interested in pursuing a chief year, here is why I chose to do it:

To hone my teaching skills

If you are interested in an academic career and want to teach students, residents, and fellows, you must know how to do so. So, this one is obvious.

I started teaching medical students early in my residency. This experience made me quickly realize that I had to read a lot to lead these sessions, because these med students often asked ridiculously hard questions about seemingly obvious things, and I did not have an answer. Sometimes, just knowing a lot about a topic was not enough — I had to know how to deliver that content to keep my learners engaged. I am still looking for a better way to learn medicine!

Chief residents typically lead, facilitate, or present didactic sessions daily to large groups of learners at different levels. This includes morning reports, noon conferences, academic half days, and simulation sessions. Most residency programs have medical education–related sessions, workshops, and information for chief residents that equip us with tools to be better medical educators.

A welcome change of pace

After working rigorously for the last 3 years during residency, I thought that a chief year would help me “take it easy” before I transitioned into an emotionally draining fellowship. What that really meant was having weekends off and a more consistent schedule which would allow me to pursue things I love, but missed doing during residency (like reading a book or binge watching a series on Netflix). However, a word of caution: Chief residents must be prepared to be on call 24/7!

I knew I wanted to pursue a fellowship even before I started residency. However, for a lot of people who choose to do a chief year, the extra year allows them to figure out truly what they want to do. They can transition into subspecialty training, academic hospitalist jobs, and primary care positions in different healthcare settings.

A great way to give back!

I was a wallflower during medical school. Coming to my program for residency helped me come out of my shell (or so I think). Moving from a different country, 8000 miles away, I was wholeheartedly embraced into the program. The incredible opportunities that I got at every point filled me with increasing confidence in myself and my abilities. That is what working in a supportive environment can do for an individual. In addition, I was also encouraged during residency to actively involve myself in other medical organizations, like the Massachusetts Medical Society and the American College of Physicians, which opened a lot of wonderful networking avenues for me. I am grateful for the support I have received personally and professionally. This made me want to contribute in my own way to the legacy of the program. I anticipated that this role would involve passionately advocating for residents, and bringing meaningful change and innovation to the program where necessary.

My family

Given the unpredictability of a fellowship match, especially with visa restrictions, doing a chief year was the most definite way for me to stay under the same roof with my husband. He started his fellowship at the same hospital during the 3rd year of my residency and had 2 more years after that to finish. Let’s face it – what we do in medicine is incredibly hard at times and having the support of family is truly a blessing!

Personal and professional growth

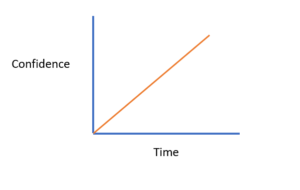

Saving the best one for the last! I applied a chief resident year, because as I viewed it as a great year for personal growth for me. Being more empowered by learning how to navigate difficult conversations, how to manage different kinds of people, how to negotiate, and how to break bad news was important to me. This is exactly what I would do in the future as a hematology/oncology doctor and, hence, I needed these skills! I have been at this job for 6 months, and my growth curve looks like this:  In the past 6 months, I found myself in situations where I dealt with conflict head on because no one else could do it. For example, it was incredibly hard to tell a resident that they would not get vacation time during their time on the floors. It is well known that these are not typical vacation weeks, but have you ever been the person saying “No” to someone?

In the past 6 months, I found myself in situations where I dealt with conflict head on because no one else could do it. For example, it was incredibly hard to tell a resident that they would not get vacation time during their time on the floors. It is well known that these are not typical vacation weeks, but have you ever been the person saying “No” to someone?

The most important aspect of my growth is in the way I give and receive feedback. As a resident, constructive criticism always made me feel uncomfortable, even though I tried to have an open mind. This year, I truly learned that ‘feedback is feedback – not good or bad.’ Feedback is always helpful if it is specific and timely.

This year is turning out to be a phenomenal year for rediscovering myself and identifying my leadership style. A chief year comes with highs and lows. It is important for anyone who is considering a chief year to evaluate why he or she wants to do it in the first place. It is a hard job as it involves A LOT of people skills, so if you are interested in applying, talk to your chief residents to get a glimpse of what the job looks like. Maybe you can even shadow them for a day!

As for me, the next time someone asks me if I did a chief year to improve my applications, I shall just chuckle to myself.

Feel free to ping me @prarthnavb on twitter for comments and thoughts.

December 3rd, 2019

To HBCU or not to HBCU? That Is the Question.

Allison Latimore, MD

Dr. Latimore is the Education Chief Resident at the MedStar Washington Hospital Family Residency Program in Washington, DC

Finding my home

There were a sea of students sitting in the auditorium, and parents were all directed to the balconies. The sound of trumpets began to blare, and the bodies of the marching band swayed rhythmically. Five minutes after soaking in the music, the ambiance, and the liveliness of Howard University, my sister and I locked eyes and decided that we were home.

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) are defined in the Higher Education Act of 1965 (amended) as “…any historically black college or university that was established prior to 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans, and that is accredited by a nationally recognized accrediting agency or association determined by the Secretary [of Education] to be a reliable authority as to the quality of training offered or is, according to such an agency or association, making reasonable progress toward accreditation.” I was privileged enough to attend Howard University in Washington, DC, which is an HBCU founded in 1867. In high school, I made this calculated decision because I was aware that Howard University was one of the top institutions for educating black medical school applicants in the United States.

Finding my career

However, as I matriculated through my undergraduate career and met other pre-meds, I began to realize that some people held the idea that going to an HBCU to prepare for medical school was not good enough. Some underestimated how well HBCUs prepare their students for a career in medicine. Unfortunately, I subscribed to these ideas for a while, due to peer influence, and struggled with the MCAT. It was not until I got a glimmer of hope, in the form of an email from Meharry Medical College, that I believed my dreams could still come true. I was offered an interview for the Master of Health Science Program, which is similar to a post-baccalaureate program. Suddenly, my thoughts of leaving the HBCU world went away. When many other schools said no, Meharry Medical College saw something in me, and said yes.

Finding my “family”

Attending Meharry gave me the same warm feeling as attending Howard. Medical students at other institutions and older physicians have described to me the feeling of being sabotaged or having “gunners” hiding information from others to get ahead. These attitudes did exist at Meharry, but were far less common than other places. No one wanted to see anyone else fail. Each class felt like a family. I never had black physicians growing up, and I surely didn’t know many in my personal life. This was the first time I was surrounded by people who looked like me and had achieved the goals that I was so desperate to achieve.

While I was attending medical school, I heard snide remarks from medical students at other institutions — remarks insinuating that it would be difficult to match coming from my institution. These ideas stem from the fact that outside of the African-American community and HBCU community, many people are not aware these schools exist. But many of my classmates matched into their number one choices at some of the top medical institutions in the country, and so did I.

Now what?

HBCUs are special places where you are, finally, not the “only one” in a room, where there is a wonderful mixture of social and academic life, where you physically see what you are aspiring to be. Unfortunately, not everyone sees the incomparable value of HBCUs. On October 1, 2019, federal funding of HBCUs expired after congress failed to extend it.

This left me questioning the future of black doctors in America, underserved patients, diversity in residency training programs, and medicine as a whole. If three major institutions that educate mainly black physicians (Howard University, Morehouse School of Medicine, and Meharry Medical College) lose federal funding, will our medical system become less representative of our patient population? There are other schools that graduate a significant number of black doctors, such as University of Illinois College of Medicine, Wayne State School of Medicine, and David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA (affiliated with Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, which is also an HBCU), to name a few, but competition for spots is fierce. I understand that people may say, “Well, minority and disadvantaged students interested in a career in medicine just need to study harder, do better on the MCAT, shadow for more hours, do more research, or simply go somewhere else.” To me, it’s just not that simple.

Fortunately, on December 4, 2019, a bipartisan agreement was reached to fund HBCUs. This proposal includes permanent annual funding of $255 million for HBCUs. HBCUs are wonderful places to get an education for both minority and nonminority students, but they cannot be the only resource for educating minority doctors. How can other institutions help promote diversity in the medical education and residency programs?

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

November 26th, 2019

Of Metrics and Medicine

Eric Bressman, MD

Dr. Bressman is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, NY

One of the least motivating requests I received routinely as a new intern was something like, “… and can we make sure this is a discharge before noon?” I recall a particularly eager nursing manager surveying the resident teams on her unit to gauge our interest in arriving even earlier each morning (5 AM, perhaps?) in order to prepare potential discharges before pre-rounding. We shared a nice laugh.

Administrators vs. House Staff

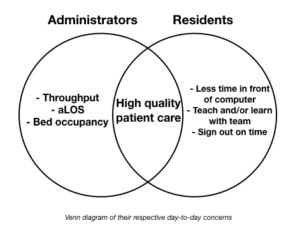

Hospital administrators and medical interns share many passions, but throughput is not one of them. As residents, we are immersed in caring for, and learning to care for, the patient at hand. Patient flow dynamics is not high on our daily list of concerns. Residents and leadership have not always seen eye to eye, but the discord has ratcheted up in an era increasingly focused on metrics. As with most issues in our convoluted healthcare system, it boils down to misaligned incentives.

When you map out the Venn diagram of what administrators and residents prioritize, high-quality patient care sits squarely in the overlapping center. Outside that, however, are things like throughput and average length of stay on the one side, and sitting down to teach the med student or getting home in time to go to the gym on the other. That isn’t to say that either side doesn’t care about the other’s issues, but, for better or for worse, it’s not what drives their day-to-day decision making.

Metrics, of course, come in a variety of flavors. There are some where the goal is universally agreed upon, whereas the methods are only variably so. Everyone wants to reduce rates of hospital acquired C. diff infection, and basic methods of preventing transmission jive with common sense. Reducing diagnosis by means of judicious testing is backed by good evidence (Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2018; 39:737; JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1792), but friction can arise between leadership and front line providers when this becomes an end in and of itself, and the patient in front of us becomes a potential statistic.

Other metrics are less intuitive to residents. Discharges before noon (DBNs) are a perfect case study. Theories abound as to the benefits of DBN for patients (e.g., getting home during the day, ability to pick up meds at pharmacies), but there is no compelling literature demonstrating any of this. This is not lost on residents. One could similarly posit downsides to incentivizing early discharges (holding patients to meet metrics, hurried coordination of services and appointments; NEJM JW Hosp Med Apr 2017 and J Hosp Med 2016; 11:859).

More important are the contradictory incentives at play. Hospital leadership view each DBN through the lens of throughput. The earlier a patient goes home, the earlier a bed opens up, and the sooner a new patient gets a room (J Hosp Med 2015; 10:664). It (questionably) decompresses the ED, and boosts the bottom line (Am J Med 2015; 128:445) . From the resident perspective, in many circumstances, an earlier discharge increases the likelihood of another admission. The reward for working hard to get the patient out early is … more work.

Solutions?

The solution should be obvious. If the hospital’s motivation is financial, then they should pass that incentive along to the residents. Not in the form of pizza parties, but as cold, hard greenbacks. This is how attendings and nurse managers are motivated in many institutions. There is hesitation, it seems, to tie bonuses to residents’ productivity. Despite improvements in resident salaries, we remain underpaid in terms of hourly wages, and there is no calculation of RVUs or talk of overtime pay. Debates over residents’ legal status notwithstanding (N Engl J Med 2011; 364:697), we are influenced by the same basic motivations as every other employee.

This same logic exercise can be applied to just about every point of contention between administrators and house staff. If leadership wants to understand how to get its front-line providers to buy into a particular metric or initiative, they should take an honest look at their own motivations. If it is purely about improving the quality of patient care, then they need only demonstrate that convincingly. If it is driven in any way by profit — which, by the way, is part of the business of medicine — then they should pass it along. Human nature is not to do more work for the same amount of money.

Residents can, similarly, do more to view the world through the lens of the administrator. Leadership is above the treetops, surveying the forest, whereas we are deep in it, hugging a few of the trees. It may mean taking a broader view of the health of a population and of the institution. But until we take the time to view the world from each other’s vantage point, friction and frustration will persist.

November 12th, 2019

Can Minor Changes in a Program Affect Resident Burnout?

Daniel Orlovich, MD, PharmD

“How did you like it there?” I ask, sitting down next to a new fellow (between bites of a plump sandwich, hoping there is no spinach in my teeth).

I expect to hear the standard resident talking points — long hours, frequent call, and ballooning student loans. Instead, she surprises me.

“Do you know how much they charged us to park there every month?”

I frequently text friends who are residents at her previous program. It is a program I respect — complex cases, the right amount of autonomy, meaningful research opportunities, and faculty dedicated to resident development. Things a resident wants in a program and things a quality program delivers.

She continues to list off things that could appear to be so inconsequential — lack of call rooms, cafeteria overcharging and closing early, and being called by her first name by staff in front of patients. I just met her, but I sense she isn’t whining or trying to win a pity award. Instead, she is opening up. Being vulnerable. Speaking trainee to trainee. I dab my mouth with the beige napkin and continue to listen.

“Do you know how many cavities I have now?!” I perk up and shake my head in disbelief as I finally swallow that bite of sandwich.

The more I think about these minor things and how they make some residents feel, the more the whole concept begins to make sense.

Minor Things

Most residents I’ve talked to will embrace the inherent challenges of residency. That means waking up early, staying late, and mastering the nuances of a field that proposes intellectual, emotional, physical, and moral challenges. Residency should be challenging. Residents know that it is temporary. But here is the sticking point: Residency shouldn’t have to be any more challenging than that.

Minor things may be making residency unnecessarily more laborious and taxing than it has to be.

At times, I get the sense that the discussion about resident burnout is centered around large system-wide changes. Such sweeping changes merit careful consideration. However, do talks about the system overshadow and crowd out an additional issue — the minor things?

Maybe improving resident burnout doesn’t require moving a mountain. Photo allowed with permission from Solving Resident Burnout.

I propose we consider these seemingly inconsequential and minor changes. This is in addition to, rather than instead of, larger changes. Things like getting quarters for laundry, going to the DMV, getting something notarized, picking up packages at the post office and, yes, going to the dentist.

In isolation, one could view these minor changes as trivial. I can certainly see how it can be taken that way. To be clear, these minor annoyances are not more important than learning to become a physician. But here is the main message — taken in the right context, although the theme is clear: “Your input is valued and we are listening, you are a human being, and we respect you.”

So here is the key question: Are there minor ways in which programs can listen to what residents want and then deliver those things without radically changing the system? This means a residency program may already have allocated the time or money. These minor measures won’t fundamentally change the well-described barriers (culture, leadership, and financial incentives) to improving the system. Nor do these minor changes excuse us from having frank discussions and acknowledging ripe areas of opportunity. However, these tiny steps are a start. They may serve as a small foundation of trust and communication between programs and residents. They may herald a new way of approaching old problems. They may seem more real and tangible. And, they may even be easier to implement, since they offer a way to gradually make changes from within the system instead of retooling the entire system.

A Recent Study

Are there any data to support using an existing framework to promote resident wellness in a minor way? Let’s look at a recent study of nearly 60 radiology residents (J Am Coll Radiol 2019; 16:221). These residents had 15 vacation days and 12 sick days. That means the program already had these days covered and funded. But here is where it got interesting — the program renamed 5 sick days and instead called them “wellness days.” Simple rebranding. These new “wellness days” could not be used on Mondays or Fridays to extend a vacation. What was the result?

- The non-burnout group used more wellness days (71%) than did the burnout group (45%).

- 86% of residents strongly agreed or agreed that “wellness days can help reduce or prevent burnout.”

- 68% of residents strongly agreed or agreed that “wellness days have had a positive impact on experience as a resident.”

On the surface, these minor changes seem, well, minor. With a closer look, they reflect an expert understanding of the following:

- Listening to residents

- Implementing cost-effective solutions

- Working within an existing framework

- Allowing residents the autonomy and freedom to engage in wellness activities of their choice

Take Home

We all know by now how bad resident burnout is. So minor solutions like the one above are reasons for hope and measured optimism. Of course, minor solutions certainly won’t fix all the structural maladies plaguing our training system. Nor are minor changes ideal. But they are a practical step in the right direction. And it is a step that doesn’t require asking for money, going through 12 committees, or depending on large governing bodies to approve changes.

The main message is this:

- Residents are on the front line — listen to them, because they may have creative solutions and insight.

- Solutions don’t have to be expensive or require a dramatic overhaul — the framework may already exist.

- These solutions may be considered “minor” but may be highly valued by residents and decrease resident burnout.

- Residents know what makes them well — allow them to engage in activities of their choice. It is not a one-size-fits-all approach.

And now I’d welcome and encourage your feedback. Would this work or not? Are there any other “minor” solutions that could be implemented?