November 26th, 2019

Of Metrics and Medicine

Eric Bressman, MD

Dr. Bressman is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, NY

One of the least motivating requests I received routinely as a new intern was something like, “… and can we make sure this is a discharge before noon?” I recall a particularly eager nursing manager surveying the resident teams on her unit to gauge our interest in arriving even earlier each morning (5 AM, perhaps?) in order to prepare potential discharges before pre-rounding. We shared a nice laugh.

Administrators vs. House Staff

Hospital administrators and medical interns share many passions, but throughput is not one of them. As residents, we are immersed in caring for, and learning to care for, the patient at hand. Patient flow dynamics is not high on our daily list of concerns. Residents and leadership have not always seen eye to eye, but the discord has ratcheted up in an era increasingly focused on metrics. As with most issues in our convoluted healthcare system, it boils down to misaligned incentives.

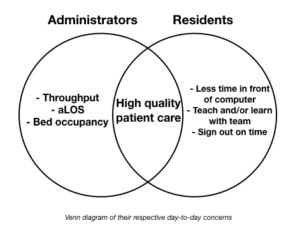

When you map out the Venn diagram of what administrators and residents prioritize, high-quality patient care sits squarely in the overlapping center. Outside that, however, are things like throughput and average length of stay on the one side, and sitting down to teach the med student or getting home in time to go to the gym on the other. That isn’t to say that either side doesn’t care about the other’s issues, but, for better or for worse, it’s not what drives their day-to-day decision making.

Metrics, of course, come in a variety of flavors. There are some where the goal is universally agreed upon, whereas the methods are only variably so. Everyone wants to reduce rates of hospital acquired C. diff infection, and basic methods of preventing transmission jive with common sense. Reducing diagnosis by means of judicious testing is backed by good evidence (Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2018; 39:737; JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1792), but friction can arise between leadership and front line providers when this becomes an end in and of itself, and the patient in front of us becomes a potential statistic.

Other metrics are less intuitive to residents. Discharges before noon (DBNs) are a perfect case study. Theories abound as to the benefits of DBN for patients (e.g., getting home during the day, ability to pick up meds at pharmacies), but there is no compelling literature demonstrating any of this. This is not lost on residents. One could similarly posit downsides to incentivizing early discharges (holding patients to meet metrics, hurried coordination of services and appointments; NEJM JW Hosp Med Apr 2017 and J Hosp Med 2016; 11:859).

More important are the contradictory incentives at play. Hospital leadership view each DBN through the lens of throughput. The earlier a patient goes home, the earlier a bed opens up, and the sooner a new patient gets a room (J Hosp Med 2015; 10:664). It (questionably) decompresses the ED, and boosts the bottom line (Am J Med 2015; 128:445) . From the resident perspective, in many circumstances, an earlier discharge increases the likelihood of another admission. The reward for working hard to get the patient out early is … more work.

Solutions?

The solution should be obvious. If the hospital’s motivation is financial, then they should pass that incentive along to the residents. Not in the form of pizza parties, but as cold, hard greenbacks. This is how attendings and nurse managers are motivated in many institutions. There is hesitation, it seems, to tie bonuses to residents’ productivity. Despite improvements in resident salaries, we remain underpaid in terms of hourly wages, and there is no calculation of RVUs or talk of overtime pay. Debates over residents’ legal status notwithstanding (N Engl J Med 2011; 364:697), we are influenced by the same basic motivations as every other employee.

This same logic exercise can be applied to just about every point of contention between administrators and house staff. If leadership wants to understand how to get its front-line providers to buy into a particular metric or initiative, they should take an honest look at their own motivations. If it is purely about improving the quality of patient care, then they need only demonstrate that convincingly. If it is driven in any way by profit — which, by the way, is part of the business of medicine — then they should pass it along. Human nature is not to do more work for the same amount of money.

Residents can, similarly, do more to view the world through the lens of the administrator. Leadership is above the treetops, surveying the forest, whereas we are deep in it, hugging a few of the trees. It may mean taking a broader view of the health of a population and of the institution. But until we take the time to view the world from each other’s vantage point, friction and frustration will persist.

May I suggest The Tyranny of Metrics by Jerry Muller. In particular, Goodhart’s law states that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to become a good measure.” Beware of monetary incentives in a profession.

Goodhart’s law certainly seems to apply in the case of DBNs; in fact, as alluded to, it’s not clear that it’s a good measure to begin with. That said, if it’s important to hospital leadership, then the incentives need to be aligned for it to be important to residents.

30 years in practice, the conflict in priorities hasn’t really shifted. With the rise of administrator numbers and reliance on us to prove our value, it’s actually worse.

Your title makes me think of this-

https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691174952/the-tyranny-of-metrics

The first question my patients usually ask on the discharge day: “when can I go/how long will it take?” Unfortunately, it often takes longer than our estimate, which is a source of patient frustration. You mentioned the lack of compelling evidence supporting some of the potential benefits of early discharge. Is there compelling evidence that early discharge DOESN’T achieve some of these ends?

Compelling- no. But this retrospective cohort study at least raises concern that this measure has the potential to become a target, a la Goodhart’s law cited above (https://www.jwatch.org/na43177/2017/02/10/does-discharge-before-noon-affect-hospital-length-stay). If a patient is ready to be discharged, then there is of course no reason to keep them any longer than is necessary. But if we incentivize noon as an arbitrary cutoff, then when people miss the cutoff, the risk is that they will start keeping patients overnight in order to meet the metric.

Very interesting and timely as I just came off a primary cardiology service where this was a new requirement in addition to the already present duties we were handling each morning. Now we were previously busy: rounding, teaching entering orders and beginning our days early. Now we had an extra responsibility – working to reward productivity could work in the setting that the environment allows for more productivity to occur. What do we stand to lose? One less lecture about the pertinent cardiac anatomy from the Fellow, more thoroughly running the list?

Personally I love metrics, but to develop a good one is tough. It requires input from your stakeholders otherwise the metric will be met without a doubt, but the underlying process could sacrifice the true objective attempting to be measured by the metric. In this case the metric to discharge before noon – implemented to have an open bed and safe patient discharges during the day to get medications. In order to fulfill this, residents will hurry to discharge without explaining medications to patients. Patient may get their medications in the afternoon, but they will know ls less about them. Discharges before noon opening up beds in the afternoon results in an ED admission that has a bed, but a team that delays seeing the patient because they are still busy putting in orders on existing patients.

If a metric is implemented, administrators need to do a thorough job of asking front-line stakeholders what environment best helps that metric be achieved. Does this mean the deadline gets changed to 2:00 PM as a compromise? Does this mean that the unit secretary prints the discharge summary and the nurse goes over it entirely with the patients?