April 30th, 2021

Riding the Second Wave

Stephanie Braunthal, DO

I just finished attending one of our inpatient teaching services, and it felt like the panel was one of the most varied and medically complex I have ever taken care of. This was my first week as an inpatient attending — as an ambulatory chief, most of my clinical time is with the residents in longitudinal clinic — and as each day brought new challenges to reason through, I kept asking myself, “Am I just rusty, or is something actually different?”

Midway through the week, I started to sense the answer was the latter. We admitted a patient for further management of multiple complications from a prolonged COVID-19 hospitalization. On the same day, one of our patients who had been with us for several days revealed she had been diagnosed with a hematologic disorder before the pandemic, but had been forced to stop treatment because it was deemed nonessential. That night, I realized almost all of my patients either had symptoms that had not been worked up because they did not see a physician (or in one case, a dentist) during the past year; because intervention had been delayed due to a freeze on nonessential services; because of long-term complications from COVID-19; or, in one case, because of a reaction to a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. None of our patients were actively being treated for COVID-19, however the pandemic had contributed to each of their hospitalizations.

Disaster medicine experts could have predicted this composition of patients on my team, as well as the increasingly complicated patients presenting to my clinic. In “Delayed Primary and Specialty Care: The Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic Second Wave,” Weinstein et al. write:

The second wave will comprise patients with chronic illness who have patiently waited to reschedule or schedule their primary or specialty care appointment to refill medications, obtain durable medical equipment, and undergo surveillance laboratory or imaging studies to gauge effectiveness of titrated therapy. This will include patients who have waited and have symptoms, signs, and other indicators of a serious illness that requires a timely diagnosis to maximize effective treatment. This will include the patients with mental illness or substance abuse who have had their outpatient treatment routines disrupted while doing their best to accept their individual, family and community stress. Eventually, these patients will need care and, like the COVID-19 response, there will be an exponential curve of presentations and consequences of delayed care: the second wave.1

Published in Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness in May 2020, the piece is a proactive call to action, outlining tactics based on proven natural disaster recovery frameworks that American healthcare institutions can use to prepare for this secondary surge of patients as they simultaneously work to rebuild their functional and financial capacities. Vital to the U.S. healthcare delivery system and deeply affected by the pandemic, residency programs might find many of these strategies helpful and directly applicable. Paraphrased examples include identifying those needed to care for acute COVID-19 patients, determining the duration of redeployment needs, creating a timeline to return to pre-pandemic functional status, keeping the non-redeployed up to date on COVID-19 best practices so that they can easily transition into the acute management role, adopting telehealth, and finding ways to protect the physical and mental health of their trainees.

Residency programs will also face unique challenges from the second wave, which they should anticipate as they prepare for the upcoming academic year. They should be aware of their institution’s social distancing protocols in order to request any necessary ancillary workspaces or workstations for the residents. Knowing this information will also help plan for the transition from virtual to in-person lectures. They need to recognize that the means by which hospitals and clinics work to recover from the losses of the past year will undoubtedly have an effect on their programs. Complex patients require more time and attention. Residency programs will likely be asked to provide more house staff to account for increased clinical demands, with additional needs in transient times of redeployment or employment freezes. The more the residents are relied on for functional capacity, the stricter time-away policies will have to be. Strategies to navigate interview season, parental leaves, and medical leaves will be of particular importance. Finally, they will need to find creative ways to support wellness, research, and education, as ongoing budgetary restrictions might continue to limit funds for these initiatives.

Residency programs will also face unique challenges from the second wave, which they should anticipate as they prepare for the upcoming academic year. They should be aware of their institution’s social distancing protocols in order to request any necessary ancillary workspaces or workstations for the residents. Knowing this information will also help plan for the transition from virtual to in-person lectures. They need to recognize that the means by which hospitals and clinics work to recover from the losses of the past year will undoubtedly have an effect on their programs. Complex patients require more time and attention. Residency programs will likely be asked to provide more house staff to account for increased clinical demands, with additional needs in transient times of redeployment or employment freezes. The more the residents are relied on for functional capacity, the stricter time-away policies will have to be. Strategies to navigate interview season, parental leaves, and medical leaves will be of particular importance. Finally, they will need to find creative ways to support wellness, research, and education, as ongoing budgetary restrictions might continue to limit funds for these initiatives.

A beach lover from New England, I have spent much time wading in the Atlantic Ocean, anxiously awaiting the moment when that first wave crashes over me, knocking me off balance and chilling me to my core. Yet, as I endure successive waves, my feet root in the sand, and my body temperature adapts. To me, the second wave of the pandemic is aptly named. We are recalibrating to a post-acute COVID-19 world, and in spite of a surge of upcoming obstacles, there is also much to embrace. Taking care of these patients forces us to grow clinically and provides ample opportunity for bedside education. Furthermore, the universality of the pandemic has given us shared experiences that allow us to connect with our patients in a way that we previously could not. We just have to make sure we prepare for what is to come. Otherwise we will be swept away with the tide, and it will be difficult to make it back to shore.

- Weinstein E et al. Delayed primary and specialty care: The coronavirus disease–2019 pandemic second wave. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2020 Jun; 14:E19. (https/doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.148)

April 14th, 2021

Top 21 Thoughts for ’21

Sneha Shah, MD

What I Wish I’d Known

Here is my advice for medical students, interns, and senior residents. These are things I wish someone had told me. I write from the perspective of an outgoing Internal Medicine Chief. Many thanks to my co-chiefs for their input and their support throughout this year.

Medical Students

- Be honest about your career interest. If you’re a through-and-through surgeon on an internal medicine rotation, tell us you’re going into surgery. Your team can then find ways to engage you in medicine from a surgical lens. We know not everyone will choose internal medicine.

- Avoid discounting your skills by saying “I’m just a medical student.” We all were medical students once. If you’re genuinely trying (and not hurting patients), no one will fault you for being completely wrong.

- If you are actively listening to your team, you’ll never have to ask, “what else can I do to help?” Figure out what your senior needs, and do it. If it’s unclear, a secret way to ask would be, “what’s left on your checklist that I can take over?”

- Don’t answer questions directed at other learners. Don’t interrupt presentations. If you’re asked a difficult question, say, “I don’t know, but let me look into it, and I can present it later.” Then, do that!

- Be in charge of the patient room! Write down team names and updates on the dry-erase board, return the tray-table and TV and blankets to their previous positions, ask whether the patient wants the door open or closed. These are little things, but we will notice you doing them. They matter more than you think.

- I know everyone tells you this, but PUT YOUR NICKEL DOWN! Giving us three treatment options and choosing the wrong one is MUCH better than giving us three treatment options and stopping! For brownie points, tell us your clinical reasoning when choosing that treatment (wrong or right), and we’ll be very impressed.

- You want your evaluations to read, “he/she worked at the level of an intern.” Figure out what this means within your team, and strive for it.

Interns

- If someone offers you the chance to go home early, take it! It’s not a trick.

- Keep a log of all the patients you see (last name, first name, and date of birth will do the trick for all EMRs). If that’s too much, at least keep track of all the patients you saw whose cases kept you up at night.

- If your expectation is to work hard, reality will certainly be easier. Those who expect a 40 hour/week residency all the time are the unhappiest.

- When picking up overnight admissions: read the H&P last. If you review the chart and come to the same conclusion as your colleague, chances are… you’re both right.

- Write less when pre-rounding. Try your best to present mostly from memory. As this gets easier to do, you’ll know your clinical reasoning skills are improving. It is possible!

- You’ve never seen HHS, and you never will. Order the DKA protocol.

- For prelims: Don’t be known as the “XYZ-prelim.” Be known as the person we want to convince to stay in internal medicine.

Senior Residents

- The calmer you are, the more your interdisciplinary colleagues will listen. Take a deep breath, don’t show your inner panic.

- Start thinking about the patient’s disposition location and outpatient medication reconciliation from day 1.

- No talking behind the backs of your intern or medical student. No talking down about other specialties in front of your learners. If you need to vent, do it with a trusted peer or chief.

- If you can afford it, buy your interns and students lunch one Sunday.

- Most conflict arises from poorly set expectations. So set the tone for your team by setting expectations. If you can joke around within your team, work will become fun.

- If you’re frustrated by a system or situation, have a strategy to prevent that from affecting the care you’re providing to the patient in front of you.

- Take responsibility. Be there for your patients and colleagues on your bad days and your good.

Bonus: While there are no ‘stupid questions,’ seek an answer before asking the question. Make an effort. Shed the helplessness.

Advice is seldom welcome, and those who need it the most, like it the least. — Lord Chesterfield

What advice do you all have for us chief residents? Do you have any other ‘must-get’ advice that I missed?

March 19th, 2021

A Leap of Faith — Residency Matching

Vivek Sant, MD

Dr. Sant is a General Surgery Chief Resident at NYU Langone Health, Bellevue Hospital, and Manhattan VA in New York, NY.

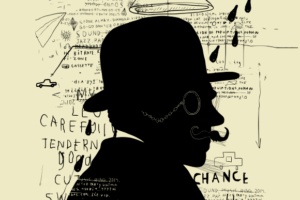

Rank lists are finally in, and Match Day is here! As I think back to my own Match Day and major decision points in my life, I remember feeling the gravity of making what I felt were life-changing decisions. Looking back, I smile when I reflect on how little of what I thought was so important has actually mattered. I am equally surprised by how large a role chance has played in these decisions, yet I am extremely happy with the outcomes! While we can’t control random chance, there are certainly some ways applicants and residency programs can better assess each other. (Disclaimer: these observations reflect my own thoughts, not those of my program).

How should residency programs evaluate applicants?

What constitutes a successful resident? If you ask 10 program directors, you’ll likely get 10 different responses. A more actionable question might be what selection metrics to optimize.

Minimize attrition? Or address the root cause?

Surgery programs nationwide have a 20% attrition rate. To minimize this, residencies seek out “grit” and “resilience” in applicants. While helpful, this conceals a larger problem. The problem is underscored by recent observations that, “Only in medicine does the death of the ‘canary in the coal mine’ lead to a search for more resilient canaries.” It is time we address the root issue instead of applying band-aids.

Programs need to honestly reflect on the etiology of attrition at their institutions. Where mistreatment or toxicity is the cause, the situation must be corrected. But maybe attrition for the right reasons is acceptable and should be normalized. A resident may realize with time that the specialty or program is not right for them, or that their priorities in life have changed — and this should be ok! How do we allow for this?

- Pre-match: medical schools should ensure students experience an accurate portrayal of the field so they aren’t surprised on July 1. Exposure as a student to the rigors of being a surgical intern (e.g., taking night-time call) has been associated with feeling more prepared as a resident and with decreased feelings of burnout.

- Post-match: residents and programs should feel empowered to discover a mismatch soon and make appropriate corrections. Normalization of a process for relocating to a specialty or program that is a better fit for a resident would provide a post hoc way of dealing with this issue.

Maximize board passage rate? The ‘objective measures’

Programs select on the basis of test scores, class rank, publications, and leadership roles. This makes sense, given the association between higher Step 1 scores and likelihood of first-time board passage.

However, we are realizing that standardized tests reveal implicit bias and might disadvantage underrepresented minorities. In response, NBME is making USMLE Step 1 pass/fail. UCSF, Stanford, and Harvard no longer participate in AOA rankings. In line with a prior NEJM Chief Resident blogger, we must look to holistic measures of a person, such as their character. But how does one measure character, and how does one do so objectively and reproducibly?

The fundamental uncertainty of ‘subjective measures’

Currently, we turn to our limited experiences with the applicant during the interview process, and the specific perspectives provided by letters of recommendation. Overall, we do not yet have adequate proxies for the qualities we need to gauge.

Fit – the solution?

Programs are fundamentally looking for people who will thrive at their program and have a positive impact. In many ways, a resident’s and program’s success are inseparably coupled. A resident may find success at a certain program because of the complementary alignment of his or her strengths/weaknesses with those of the program. While interviewing for residency, I was advised to “Trust your gut, go where you perceive the best ‘fit’ between yourself and the residents/faculty/program.” Only now, after the breadth of my experiences over the past 6 years, am I beginning to appreciate the value of this advice.

What should students look for in a program?

As a student, you can’t possibly know the full extent of what you’re getting yourself into. It wasn’t until my senior years of residency that I began to appreciate the gravity of the field — the loneliness and depth of responsibility one feels for one’s patients when having to make life-altering decisions.

There are other aspects of uncertainty from a student’s standpoint. Ranking a program because of well known faculty carries the risk that they might leave before you graduate or even get there. I believe the answer to the uncertainty, on the student’s end, too, is fit. Honestly assess yourself and your core values. Then find a place whose values match yours. Seek out examples of how they have demonstrated commitment to the things you find important. And do your best to get an accurate exposure to the field, the programs, and the culture: Seek out opportunities to act as an intern on sub-internships, take overnight call, and do visiting rotations.

Lessons learned from interviewing in tech

Prior to medicine, I worked in the tech industry, where technical interviews are used as a means to assess a candidate’s ‘technical chops’. Despite improvements over the past 30 yrs, these interviews still don’t predict who will succeed or fail at a company. Only 20% of the best coders perform consistently well at technical interviews. But it seems that practice makes perfect: applicants who attend more practice and actual interviews end up performing better than those who receive less practice. As I went through residency interviews, I found myself becoming progressively more calm, confident, and truly myself. Residency applicants too would benefit from additional practice sessions until they feel they have achieved the confidence to put their best foot forward.

From applicant to interviewer — insights from the other side of the table

Applicants and programs both seek to put their best foot forward. So how does one cut through the chaff and start to really understand someone’s character? One way is to explore character-defining experiences. I understand much better now the intent behind the questions, “Tell me about a weakness” or “Tell me about a difficult experience.” These are meant to allow an applicant to showcase their character, humility, trustworthiness, work ethic, stress response, and ability to grow.

We often end up selecting people similar to ourselves. We like an applicant when we find something to connect with them about. Often, I found two interviewers would have disparate experiences with the same applicant. One person viewed the candidate as engaging and passionate, while the other found them disinterested. If you’re looking for more than “people like yourself,” you need interviewers with a variety of backgrounds and interests so that a quality applicant is not overlooked.

Conclusions

In medicine, we are comfortable making decisions based on imperfect information. The applicant selection process is no different. No matter how exhaustive the process, invariably, we must make a leap of faith. A lot of luck and chance also factors into the process. During residency interviews, I eagerly anticipated my interview at a program in Miami. However, unforeseen circumstances clouded the visit. My most lasting impressions are a late flight arrival (at 2 am on interview day), and a belligerent taxi driver at the airport! All the same, I am very happy with how the overall process turned out.

To the programs:

- Structural issues causing attrition should be fixed. Attrition for the right reasons should be destigmatized.

- Help your medical students get an accurate exposure to the field.

- Seek to better assess an applicant’s intangible traits.

- Ensure applicants meet with a variety of interviewers.

- Optimizing for fit = mutual success

To the applicants:

- Immersive sub-internship experiences can help you accurately appraise a specialty.

- Practice makes perfect!

- Get real exposure to other programs through visiting sub-internships.

- Understand a program’s values and assess its alignment with yours.

- Check your boxes and, in the end, trust your gut when looking for the right fit.

It has been an honor to have been a part of the application process this year. Good luck to all the applicants on Match Day 2021!

It has been an honor to have been a part of the application process this year. Good luck to all the applicants on Match Day 2021!

March 5th, 2021

The Season of the Second Year

Stephanie Braunthal, DO

Chief year has taught me that, although residents progress through training linearly, the educational year itself is cyclical, with predictable “seasons” that are marked by specific events and focus on different populations within the residency body. With the completion of intern orientation, the fellowship match, and residency recruitment, there is a palpable shift to the progress and futures of members of the PGY-2 class. Filled with the planning of leadership retreats, selection of future chief residents, and preparation for the imminent fellowship and job application deadlines, I have deemed this time of year the “Season of the Second Year.”

Second years are the proverbial middle children of the residency program. Already onboarded and not yet needing post-graduate placement, they often feel overlooked. Yet in reality, PGY-2 is one of the most challenging and transformational years in internal medicine residency. With the change of a calendar date, residents suddenly gain significantly more autonomy, lose the security of having a senior to help with clinical reasoning and writing orders, and, in many programs, shift their responsibilities from being a task manager to being a supervisor. In the midst of this huge clinical transition, they watch their third year peers going through the fellowship match and job processes, only to realize that there is a limited time to define themselves within the program and to make crucial decisions about their own career trajectories. From the fear of being a senior on nights by myself, to the anxiety of not yet having chosen a specialty, to the insecurity of comparing my productivity and qualifications to those of my peers, I remember these feelings vividly.

Second years are the proverbial middle children of the residency program. Already onboarded and not yet needing post-graduate placement, they often feel overlooked. Yet in reality, PGY-2 is one of the most challenging and transformational years in internal medicine residency. With the change of a calendar date, residents suddenly gain significantly more autonomy, lose the security of having a senior to help with clinical reasoning and writing orders, and, in many programs, shift their responsibilities from being a task manager to being a supervisor. In the midst of this huge clinical transition, they watch their third year peers going through the fellowship match and job processes, only to realize that there is a limited time to define themselves within the program and to make crucial decisions about their own career trajectories. From the fear of being a senior on nights by myself, to the anxiety of not yet having chosen a specialty, to the insecurity of comparing my productivity and qualifications to those of my peers, I remember these feelings vividly.

As it has with so many aspects of medical education, the pandemic has made the experience of being a second year significantly more difficult. Between intermittent clinic and consult closures, the need to pull residents for redeployment, and some residents missing rotations for COVID-19-related medical leave themselves, this class has had less access to electives that would otherwise help them evaluate different specialties, establish in-person mentorship, and be evaluated clinically by the faculty who will write their letters of recommendation. Furthermore, as all of us have experienced, they are unable to access the people and activities that help relieve stress outside of residency, and many have suffered significant loss from the virus itself.

The way that this year’s second year class has managed to find opportunities amidst the aforementioned limitations speaks to their resilience and adaptability. However, the inequities of their access to clinical experiences and mentorship due to the pandemic has made me question whether the timeline and expectations prior to applying to fellowship need to be adjusted to allow for residents to have the opportunity to optimize their clinical growth before solidifying and propelling their career. Even under normal circumstances, when residents focus too much on research or other projects that they take on to improve their CVs, their clinical performance sometimes suffers. Further, if they feel the pressure to commit to a specialty so early in residency, they may miss out on the realization that they are better suited for something else.

Moving back the timeline for fellowship applications by even a few months would not only relieve stress on the individual residents, it might also have widespread program benefits. If third-year residents interview later in the year, they will be more present to mentor and teach the interns in their early months; by the time seniors are interviewing, the second-years will have enough experience to easily cover the teams. Further, it could alleviate the need for program leadership to focus simultaneously on onboarding new interns and ensuring all fellowship documentation is appropriately submitted, both heavily administrative processes with strict deadlines in June and July.

Moving back the timeline for fellowship applications by even a few months would not only relieve stress on the individual residents, it might also have widespread program benefits. If third-year residents interview later in the year, they will be more present to mentor and teach the interns in their early months; by the time seniors are interviewing, the second-years will have enough experience to easily cover the teams. Further, it could alleviate the need for program leadership to focus simultaneously on onboarding new interns and ensuring all fellowship documentation is appropriately submitted, both heavily administrative processes with strict deadlines in June and July.

Creating such a substantial change in the seasonal pattern of the residency year would require buy in from myriad stakeholders across multiple specialties and within the graduate medical education community at large. If considered, it may take years to achieve. In the meantime, we in program leadership must focus on measures that help residents flourish within the current framework:

- Provide structured advisor, mentor, and coaching programs that prepare residents for crucial points on the residency timeline for skills acquisition and career decisions.

- Ensure broad exposure to clinical rotations early in training, with buffered time for the resident to explore electives.

- Allow interns to practice skills that will be unique to being a senior resident. This can be through embedded education and graded autonomy on the floor, workshops, or retreats with opportunities for reflection and goal-setting.

- Encourage fellowship directors to be transparent about their expectations of what constitutes a strong applicant. This will help residents prioritize what they should be working on outside of their clinical responsibilities.

- Anticipate that the pandemic is not over, and that the closures we previously faced may recur. Work with subspecialty education coordinators to find creative ways to achieve alternative education and mentorship if the residents cannot rotate with their fellows and faculty in clinic or consults directly.

- If your jeopardy pool can afford it, try to minimize calling in residents off of electives when they are rotating in their desired specialty.

The Season of the Second Year is as invaluable for the program as much as it is for residents. As we evaluate the clinical and academic progress of our trainees at such a pivotal point, we are forced to reflect on our own strengths and weaknesses that may have engendered or hindered their success. Further, the yearly process of selecting new chief residents allows us to focus on the future of the program, as well as what qualities we seek in our leadership.

The Season of the Second Year is as invaluable for the program as much as it is for residents. As we evaluate the clinical and academic progress of our trainees at such a pivotal point, we are forced to reflect on our own strengths and weaknesses that may have engendered or hindered their success. Further, the yearly process of selecting new chief residents allows us to focus on the future of the program, as well as what qualities we seek in our leadership.

With that, I open the discussion to the readers. How did you feel when you were second years? What measures did your program take to help you succeed, or that you wish had been offered? Do you think it would be feasible or useful to shift the seasons within our academic calendar?

February 26th, 2021

Toward a Pedagogical Shift

Sneha Shah, MD

“If we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday’s, we rob them of tomorrow.”

— One summation of philosopher John Dewey

The Why can’t I just Google it? Problem

Imagine seeing a patient with symptoms you suspect mighty be the result of a medication side effect. But you’ve forgotten the mechanism of action of this medication. You left your pocket pharmacology book at home, and the hospital library is 15 minutes away. There are no pharmacists on the wards for you to consult. I imagine there was a time when memorization in medicine was crucial. I am not saying it isn’t now, but I propose that it is less so. In less than 1 second, Google can tell me the mechanism of action of any medication. By conceding that the availability of lightning-fast information at our fingertips is an argument against memorization, are we doing a disservice to our learners?

Pedagogical shift, proposal 1: Let’s teach our learners how and when to appropriately utilize modern, web-based tools. More importantly, let’s teach them why it is still important to engage in some memorization instead of always reverting to “Why can’t I just Google it?” If you’ve ever run a Code Blue, you know there are times when your memory must serve you under extreme pressure. I would like to see medical education emphasize the why instead of the what. Any modern learner can Google the what (i.e., what is the mechanism of action of labetalol?). So let’s set aside testing learners’ memories and instead re-allocate time to teach them why a master clinician chooses labetalol instead of another agent.

Pedagogical shift, proposal 1: Let’s teach our learners how and when to appropriately utilize modern, web-based tools. More importantly, let’s teach them why it is still important to engage in some memorization instead of always reverting to “Why can’t I just Google it?” If you’ve ever run a Code Blue, you know there are times when your memory must serve you under extreme pressure. I would like to see medical education emphasize the why instead of the what. Any modern learner can Google the what (i.e., what is the mechanism of action of labetalol?). So let’s set aside testing learners’ memories and instead re-allocate time to teach them why a master clinician chooses labetalol instead of another agent.

USMLE is already moving toward making Step 1 Pass/Fail; many medical schools are shifting to a longitudinal curriculum. As someone who has come from “bench to bedside” and now is arriving back at “the bench” for ongoing enhancement of my understanding of pathophysiology, I wish I would have been taught with the above lens.

The I don’t have time Problem

Residents of today have quite a bit asked of them! Pre-round efficiently, present that data flawlessly, tend to sick patients, admit new patients, run family meetings, discharge patients (ideally before 11AM), write your notes quickly but without copy forward so the attending can co-sign, and sign-out in a timely manner so you don’t break duty-hour restrictions. All this, along with the added pressure of attending educational conferences and reading about patients. It’s hard. I worry that the residents (and the perceived “cheap labor” they provide) have been misappropriated to doing more and more. Is there a way for residents to see a similar volume of patients but re-allocate their limited duty hours back to being learners?

Pedagogical shift, proposal 2: Let’s challenge our learners to practice mental dexterity. With the ubiquity of workstations on wheels in many hospitals, is a model of “discovery rounds” better? Here, time typically spent pre-rounding can be spent at the bedside, reading about illnesses, and prepping the rest of the afternoon for success. This model may be more difficult for junior learners (medical students and interns), as it requires one to synthesize data quickly, assess the patient’s condition, and derive a plan. For senior residents, this may be the necessary way forward for critical clinical reasoning. This method might also help shift the traditional model of data transference (from the pre-rounder to the rest of the group) to one of dialogue.

The Stuck in a routine Problem

Everyone learns differently — some visually, some aurally, and some in a tactile manner. One of my favorite education philosophers is Paolo Freire. In his Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he writes, “education is suffering from narration sickness.” It is not by pretending we are empty vessels to be filled with medical knowledge that one becomes the type of provider they want to be; but rather by experiential learning through a growth mindset and empathetic dialogue will we become our best physician self. That’s a bunch of fancy words to say, as a chief, I notice a decline in enthusiasm toward attending educational opportunities and wonder why this is the case? What changes would the learners prefer?

Pedagogical shift, proposal 3: Let’s bring back the joy of teaching and learning. Celebrate being wrong in a safe space and use a dialogical and interactive model of teaching rather than narration. This has been a priority for me and my co-chiefs this year. We even created a “Stump the Chiefs” conference to get in the hot seat ourselves — which you can find on our YouTube channel. Why not try “reverse-pimping” while you’re on the wards? Here, the learners ask questions of the attending to determine how he or she catalogs a patient’s presentation and how a treatment plan is developed. It is our duty to keep our learners engaged. It’s time to get creative, pique some curiosity, and make learning fun again!

Let us no longer rob our students of tomorrow.

February 18th, 2021

The Human Side of Medicine — Grieving the Loss of Our Patients

Masood Pasha Syed, MBBS

“The life of the dead is placed in the memories of the living” — Marcus Tullius Cicero

Growing up in a family of physicians, I was exposed early to healthcare from the provider side. Some days, my father would come home late after a long surgery with an unanticipated complication or an unexpected outcome and would silently eat his dinner while listening to us talk about how our day went. As an animated child, I always had many things to tell him, but I realize that I never asked him how his day had gone. Throughout my career though, I have come to realize the power of being comfortably silent with your loved ones. We all need that unique outlet to destress, and now I understand that it was his family for my dad.

Losing patients is never easy — the permanence of loss with death highlights our lives’ temporary nature. Having been trained to save lives and treat diseases to help cure our patients, it is challenging to deal with loss emotionally, physically, and intellectually.

The ongoing pandemic has definitely tilted this equation even more and has left most of us with hardly any time to truly internalize and reflect on losing patients. It has been surge after surge, with the continuous onslaught of COVID-19. Fortunately, one of the success stories of this decade will be the vaccine and its role in reducing the number of deaths, provided we reach an adequate number of vaccinated individuals. Politics and conspiracy theories aside, we must not forget the power of science and choose it over our own personal differences with each other’s thought processes. As we start seeing the beginning of the pandemic’s end, the road to recovery will be a long one ahead. We need to continue planning the rollout of vaccines, including mass production and administration to the general public, consider our response to the newer viral strains, and, at the same time, address the loss we all have seen so far. I think it is high time to restart (continue) the conversation about physician grief and better ways to deal with it.

Dealing with a patient’s death is a profoundly personal experience, and coping mechanisms will vary. Although our ways of dealing with adverse outcomes may differ from each other, there is a root paradox with confronting death, since it negates everything we are taught and inclined to do — be it saving lives or curing diseases. Acknowledging this paradox can be a valuable starting point, as we learn to recognize our own feelings and patterns of dealing with loss. Some insightful pointers that I have received from my mentors are these:

Dealing with a patient’s death is a profoundly personal experience, and coping mechanisms will vary. Although our ways of dealing with adverse outcomes may differ from each other, there is a root paradox with confronting death, since it negates everything we are taught and inclined to do — be it saving lives or curing diseases. Acknowledging this paradox can be a valuable starting point, as we learn to recognize our own feelings and patterns of dealing with loss. Some insightful pointers that I have received from my mentors are these:

Honesty and Empathy: Being completely honest with our patients and their families is vital and goes a long way in overcoming their fear and uncertainty. Prioritizing their comfort is essential and helps address common goals. Choose a private area to communicate bad news and express sincere empathy. Always ask if anything else can be done to help families with the grieving process. We often learn how to be better in these trying times by listening to what families have to say.

Honesty and Empathy: Being completely honest with our patients and their families is vital and goes a long way in overcoming their fear and uncertainty. Prioritizing their comfort is essential and helps address common goals. Choose a private area to communicate bad news and express sincere empathy. Always ask if anything else can be done to help families with the grieving process. We often learn how to be better in these trying times by listening to what families have to say.

- The power of choice (letting go of guilt): Remember that it was our choice to be here in this role, caring for patients. We must not forget our conviction for helping others and reducing suffering, which led us to medicine. Refreshing our perspective regularly helps us realize how far we have come, while we continue to learn from our ongoing experiences. Unfortunately, medicine is not an exact science. Sometimes, practicing it can be an art, especially while traversing through some grey areas. Being comfortable with not knowing it all makes us human. Setting ourselves on a path where only saving lives is acceptable may not be an ideal goal; instead, focusing on respecting patients’ autonomy and wishes will help us see life and death as more than success and failure.

Seek support and normalize grief by creating a safe space: Physicians are not superheroes and cannot fix everything. One of my mentors uses the “Magic Wand” analogy and tells her patients that she would surely fix everything if she had a magic wand. Unfortunately, none of us have one. I have found that being honest about my inability to fix everything is very powerful during patient encounters. I have seen it humanize physicians. Remember, it is okay to cry with your patient’s family, and it does not make you a weak person or any less of a doctor. Showing your emotions in such a situation helps physicians and patient families grieve together and achieve closure. It also helps to talk about losing patients among peers in a supervised setting and perhaps with professional psychologists present, if needed. It also helps to listen to your colleagues’ experiences. Creating safe spaces at work on a regular basis can definitely be therapeutic. We are a team, through life and through death.

Seek support and normalize grief by creating a safe space: Physicians are not superheroes and cannot fix everything. One of my mentors uses the “Magic Wand” analogy and tells her patients that she would surely fix everything if she had a magic wand. Unfortunately, none of us have one. I have found that being honest about my inability to fix everything is very powerful during patient encounters. I have seen it humanize physicians. Remember, it is okay to cry with your patient’s family, and it does not make you a weak person or any less of a doctor. Showing your emotions in such a situation helps physicians and patient families grieve together and achieve closure. It also helps to talk about losing patients among peers in a supervised setting and perhaps with professional psychologists present, if needed. It also helps to listen to your colleagues’ experiences. Creating safe spaces at work on a regular basis can definitely be therapeutic. We are a team, through life and through death.- Gratitude and prioritizing self-care: Being thankful to the people who care for us and the blessings we have can be very powerful and definitely can add meaning and purpose to our lives. Caring for others can continue to be fruitful only when you begin with yourself. Practicing personal wellness regularly results in professional wellness. Finding a hobby and doing something you genuinely enjoy outside of medicine helps heal your body, mind, and soul.

To conclude, any new disease will always bring with it its own uncertainties. Although we have had coronavirus infections before, we have never had them at such a pandemic proportion. This has resulted from many factors, the scope of which is beyond this blog piece but, needless to say, we have many things to unwrap in the time that lies ahead. Not knowing the natural history of a disease and the pathogenesis of its symptoms made many of us feel like we were stuck in a tunnel, blinded by its darkness, trying  to find a way out.

to find a way out.

How can we treat a disease we do not fully understand? As we answer this question, I am appreciating the power of fundamental principles and basic research with all the developing literature. I thank all the great scientific minds and the gallant efforts of our healthcare workers/allied staff members as we even begin to see the light, hopefully, at the end of this tunnel.

I invite the readers to share their experiences with grieving through this pandemic to continue this narrative and help with the healing process.

February 4th, 2021

Engaging with History: Why Do the Actions of Nazi Physicians Matter in Medicine Today?

Holland Kaplan, MD

The reflections and photos in this post are a result of the immersive experience I had via the Fellowship at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics in 2016.

Many assume that Nazi physicians were antisocial, sadistic psychopaths. But viewing the perpetrators of the Holocaust as morally deficient is simply inaccurate; in fact, the Nazis physicians were often well-known, highly respected individuals at the tops of their fields. The Nazi philosophy was based on scientific and historical factors that developed over many years and culminated in the Holocaust. In the actions of Nazi physicians, we can see how many important principles in the practice of medicine were broken. Studying the actions of Nazi physicians reinforces that we may all be capable of violating these principles, and we must be constantly vigilant to maintain our compassionate, humanistic, ethical practice of medicine.

Enhancing patients’ right to healthcare

The Nazis had a warped view of “public health” that centered on “racial hygiene,” a concept that represented the evolution of ideas introduced in Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. By 1920, the phrase “life unworthy of life” was commonplace in Germany in referring to terminally ill patients and psychiatric patients. When Nazi doctor Fritz Klein was asked how he was able to murder people after having taken the Hippocratic Oath, he responded, “Of course I am a doctor and I want to preserve life. And out of respect for human life, I would remove a gangrenous appendix from a diseased body. The Jew is the gangrenous appendix in the body of mankind.” The moment we believe that certain groups of people, whether elders, socioeconomically disadvantaged, incarcerated, disabled, or with whatever other trait we choose, are less worthy of healthcare is the moment we start to invalidate their humanity and their worthiness of life. The American healthcare system unfortunately often makes it difficult to ensure that all groups receive equitable healthcare. Thus, it is our job as physicians to advocate for our patients to the best of our ability at the individual, state, and national levels.

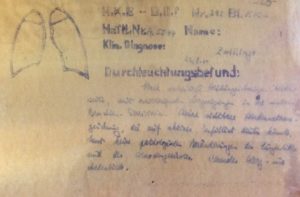

Informed consent is critical in clinical medicine and research

The Nazi doctors enacted a variety of non-consensual human experiments. These experiments included determining the “most effective” means of killing people (e.g., injections of phenol vs. starvation vs. gassing), freezing subjects to identify effective treatments for hypothermia, and bone grafting experiments to test the efficacy of newly developed medications. The purpose of many of these experiments was to identify efficient methods for killing people the Nazis deemed “undesirable” and to perform general basic science research in which a given Nazi doctor had a special interest. From post-war scrutiny of these experiments arose the Nuremberg Code, a set of guidelines that outlines principles of research ethics in human experimentation. From consent in research projects to day-to-day consent for medical procedures, it is critical that we ensure our patients are well-informed of the risks of the procedure to which they are consenting and that they are voluntarily agreeing to undergo the intervention.

Description of the results of a lung x-ray within the experiments conducted on twin children by Dr. Joseph Mengele, photo taken at Auschwitz in June 2016

Importance of challenging the hierarchy

The sociological phenomenon of people’s willingness to follow orders also played a prominent role in the actions of the Nazi physicians. Stanley Milgram’s famous 1961 obedience experiment showed that people exhibit a chilling willingness to follow orders, particularly when there seems to be a greater cause and an authoritative figure giving orders. In his testimony in the Nuremberg Trials, defendant Dr. Karl Brandt was asked whether the ultimate responsibility for the medical crimes that took place in the Nazi concentration camps should fall on the state or on the physicians. Dr. Brandt responded, “In my view, this responsibility is taken away from the physician because the physician is merely an instrument. The feeling of a special professional, ethical obligation has to subordinate itself to the totalitarian nature of the war.” The dissemination of responsibility from an individual to a group of people can enable individuals to engage in unethical actions. Impenetrable hierarchies in medicine continue to exist to varying degrees, often differing between specialties and institutions. However, the idea that strict adherence to a hierarchy can negatively affect patient safety and patient care is commonly taught in medical schools. As a result, there are measures in place that intentionally disrupt the chain of authority in medical practice. For example, a patient’s nurse may be specifically sought out during a medical team’s rounds to ensure that any of his or her concerns are addressed. Formal avenues exist for medical students to lodge concerns regarding mistreatment of themselves or patients. Centers of professionalism and ethics abound in medical schools to address these types of violations.

Taking action against dehumanization and decreased empathy in medicine

In their participation in concentration camps, Nazi doctors were able to psychologically distance themselves from their actions by dehumanizing prisoners (e.g., using prisoner numbers instead of names, stripping people of their clothing and other belongings, viewing individuals as animals instead of people). In the modern practice of medicine, constant exposure to the pain and suffering of other people often has a numbing effect. Medical professionals may eventually become less susceptible to having an emotional response to another person in pain. It is a well-studied phenomenon that medical students become decreasingly empathic as their training progresses. This apathy towards pain and suffering that may develop over time in physicians is concerning, because it may enable a similar apathy when immoral actions occur. Those who commit evil do not necessarily have evil motives. This decreasing empathy and lack of self-awareness in the medical profession is a systemic problem that physicians should be aware of and which needs to be continually addressed. Some possible interventions, many of which are already occurring, are to include courses and activities in medical practice that enable reflection and empathy. Examples include patient memorial services, reflective writings, and facilitated small-group discussions on the role of empathy in medicine. Encouraging and enabling physicians to have other roles in their lives can also be helpful, as a person who functions as a physician, a mother, a wife, and an active community member has the opportunity to re-orient herself and look at her role as a physician from other perspectives.

Ultimately, every historical age has its own outlook and attempts to solve the problems it faces in unique ways; it is by studying how these historical problems arose and the results of their attempted solutions that we can start to have a basis for solving problems of our own time. By learning from the atrocities committed by Nazi physicians, we can hope to avoid similar actions in the future and hopefully better the practice of medicine.

References

Alexander L. Medical science under dictatorship. N Engl J Med 1949 Jul 14; 241:39. (https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM194907142410201)

Chen D et al. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. J Gen Intern Med 2007 Oct; 22:1434. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0298-x)

Lifton RJ. The Nazi doctors: Medical killing and the psychology of genocide. 1986. New York: Basic Books.

Milgram S. Behavioral study of obedience. J Abnorm Psychol 1963 Oct; 67:371. (https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040525)

January 22nd, 2021

Gratitude – Reflections on 2020

Vivek Sant, MD

Dr. Sant is a General Surgery Chief Resident at NYU Langone Health, Bellevue Hospital, and Manhattan VA in New York, NY.

2020 was a tough year. With natural disasters around the world, a global pandemic, and significant social and economic upheaval both in the U.S. and abroad, no one has emerged unaffected. Especially in medicine, we have acutely experienced our share of grief and loss and have witnessed humanity in its most broken state. In the darkness, however, we have still found glimmers of hope and light. Reflecting on the past year, I would like to share these moments of gratitude I have experienced.

Resilience in the COVID era

As the lockdowns and shelter-in-place orders were implemented, many industries experienced economic crisis, companies were forced to shut down, and many “non-essential workers” were laid off. I am fortunate to have had a job during this pandemic. Moreover, as a physician, I am grateful to have had the appropriate training and to have been in a position to take care of patients during this pandemic. Working at Bellevue, America’s oldest public hospital, and the Manhattan VA, I appreciate the opportunity to have taken care of patients with nowhere else to turn, and to have taken care of our veterans, who have served and protected our country.

During the early months of the pandemic, New Yorkers came together to support each other in several moving demonstrations of strength and unity. Several of my non-medical friends, hearing horror stories of healthcare workers experiencing PPE shortages, wanted to help in whichever way they could and offered me their own, saying, “I have two N95 masks, you need these more than I do.” There was a constant outpouring of donations of coffee and meals for healthcare workers every single day for months — from restaurants, companies, friends, family, and New Yorkers who just wanted to express their support and contribute to the effort any way they could.

Within the hospital itself, physicians of every specialty and hospital staff of every background (nurses, respiratory therapists, lab techs, custodial staff, greeters) banded together to help each other and to help patients get the care they needed. No task was beneath anyone, and everyone was focused on getting our patients — and each other — through each day. The sense of camaraderie was truly inspiring! People were re-deployed to tasks that were normally outside the scope of their pre-COVID roles, and they performed them with grace. Residents and PAs of every specialty staffed COVID units, OR PAs took care of inpatients, OR nurses started working as ICU nurses, and outpatient nurses administered COVID tests. I even saw general surgery attendings in their 50s and 60s thriving as re-deployed interns on medicine wards. (Believe it or not, they somehow figured out how to put in orders!)

In the ICUs, some of my patients were on OR ventilators that would break down every 12 hours, or single-mode ventilators that looked like 1950s video game consoles — a far cry from the fancy ventilators we normally use! But I was grateful we had something with which to ventilate our patients. And to wrap up the year, a miracle of modern medicine arrived — multiple COVID vaccines developed in less than 12 months.

Professional growth

In my own professional life, I found much to be grateful for as well. This past August, I matched at an incredible endocrine surgery fellowship, at UCLA, where I will be headed this summer! I am grateful for my patients, who have taught me so much — learning from their pathologies as well as the resilience so many of them displayed in the face of receiving difficult news. I am indebted to my mentors, surgeons who have been eternally patient in training me and who inspire me daily to be the best surgeon I can be. I am grateful for my junior residents and medical students, who are intelligent, hard-working, make my life easier, and ask insightful questions that push me to advance my own understanding of medicine. Over the past year, I am grateful for all of these experiences that have helped me mature significantly as a physician and surgeon.

Personal satisfaction

I am fortunate to have family and friends who love and support me — and help bring out the best in me. Over the past year, I have met so many people, both in and out of work, who have helped me expand my perspectives on life. And finally, I have rediscovered my love for running! I ran cross-country and track in high school and used to love trail-running in my hometown. Going for a run in Central Park, or along the East River, revitalizes my mind and body, and I love exploring the city. In addition to improving my fitness and releasing endorphins, running helps me reconnect with nature and with my body. It allows me to practice mindfulness, self-reflection, and self-affirmation, and I really appreciate this meditative aspect.

With such a tough year now in our rearview mirror, this retrospective is not meant to repaint our collective experience in a rose-colored hue, nor meant to minimize anyone’s grief. Instead, I offer this recollection of moments as a means to share my gratitude to all those around me who helped me make it through the difficult year that was 2020.

With such a tough year now in our rearview mirror, this retrospective is not meant to repaint our collective experience in a rose-colored hue, nor meant to minimize anyone’s grief. Instead, I offer this recollection of moments as a means to share my gratitude to all those around me who helped me make it through the difficult year that was 2020.

What were you grateful for in 2020?

January 12th, 2021

Vaccine [Rollout] Reactions — In Support of Residents

Stephanie Braunthal, DO

During the first week of the U.S. national vaccine rollout, news outlets reported a protest after a major medical center’s initial COVID-19 vaccine distribution list did not include almost the entirety of their house staff. Less publicly, I have heard about additional instances across the country where trainees as a whole have been or felt excluded from receiving a dose from the first shipment of vaccines. A common trope among the stories in which the slight was accidental has been that, somewhere along the line, nonmedical staff misunderstood the role of medical trainees in patient care, did not know where they belonged administratively, or in one case, did not know the difference between residents and fellows and inadvertently left the former off the communication, even though a substantial number actually were due to be vaccinated.

Hearing about such clerical errors reminds me that the hierarchy of academic medicine is not intuitive to those outside of the field. For the most part, the result of this is fairly benign, and usually results in explaining things to friends and family (such as the difference between residency and fellowship, or that, as an internist, I haven’t delivered a baby since medical school). For patients, not understanding the hierarchy can create confusion and even frustration. They want to know why they need to wait to meet the attending physician in a teaching clinic, or why they can’t get a medication refill after discharge by the resident who took care of them in the hospital.

Doctor at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center receives a COVID-19 vaccination. Dec 14, 2020. (DoD photo by Lisa Ferdinando) CC BY 2.0

Residents and fellows can also be negatively affected by others misunderstanding their role. Their confidence can be shaken when a patient demands, “I want to see the doctor,” when they enter the room (not knowing that they had been mislabeled as a student); or they might feel alienated if they don’t have a workspace on a rotation because they are not formally employed by that department. Building up over time, these types of seemingly harmless encounters make many trainees feel like they do not belong or are not appreciated in the place to which they devote so much of their lives. Unfortunately, these perceptions were amplified for those who were not included in the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, no matter how unintentional the slight(s) may have been.

So, what will help trainees trust that their programs, institutions, and patients value and respect them? After reflecting on my own and my peers’ experiences in their programs, transparency, equity, agency, and recognition appear to be fundamental. Some suggestions of ways to implement these principles include:

- Deliver honest and consistent communication about operational matters directly to house staff.

- Offer the same opportunities to trainees as are given to hired employees (e.g., retirement matching, health benefits, vacation time, and appreciation weeks).

- Ensure residents and fellows understand where they fall in both the educational and administrative framework, such that they are aware of all the channels by which they can direct questions and advocate.

- Include residents and fellows in institutional initiatives that affect them.

- Devote time during orientation of nonphysician employees to the structure of medical education. Ensuring that other healthcare providers and administrative colleagues understand the different roles of physicians will not only improve teamwork, it will also help them communicate with patients on our behalf.

- Recognize trainee efforts and accomplishments publicly.

These measures not only contribute to wellbeing and morale, they also engender a higher likelihood of retaining the resident or fellow after training.

One of the lessons I have learned in my short time thus far in program leadership is that sometimes asking how we can support is as important to intuitively providing support. The vaccine rollout has sparked meaningful conversations about what it means to feel valued and respected in one’s place of work, particularly as a trainee. My hope is that the dialogue continues beyond the pandemic and results in lasting change.

December 31st, 2020

What Time Is It?

Sneha Shah, MD

How many minutes have you given yourself to read this post?

There was a time when none of us could tell time. Imagine not knowing what the ever-moving hands of a clock are trying to reveal. My memories skew, but in that era before I could tell time, all I remember is laughter, effervescence, and the occasional injury. (The first time I hit my “funny bone” was quite the scare)!

Now, we can’t seem to escape it. No matter where we look: car dashboards, microwaves, and the multi-functional faces of Apple iWatches, which dare tell time once in a while. Such a fascination with constant timekeeping has robbed us of ever being fully present in the present. In fact, the “present” is such a gift that the verb and noun for it are identical.

As a medical student, I couldn’t wait to get started as a doctor. Then, it was time to be one — intern year. Lo and behold, inaugural moments of internship transformed into hurried hours and then into dismaying days. The hard work was setting in, and I found myself rushing toward the end of each day, wondering if I’d made the right choice. The excitement and wonder of becoming a doctor that I felt as a medical student had passed as quickly as 80 hours did in a week. The more I looked at the clock, waiting for 5 o’clock to come, the slower it seemed to arrive. Shockingly, in all this perceived slowness, the work became a blur — akin to the trees zooming by a fast-moving commuter train. Still, for this high school “mathlete,” a week of vacation never seemed as long as a week in the ICU.

Are you multi-tasking while reading this?

Even as I gained knowledge and fostered my clinical competency, whatever amount of wonder was left continued to fade. To stop myself from reaching whichever breaking point I was accelerating toward, I hit the breaks and started to search, or rather, re-search for what I knew I once had. Much like the stuttering second hand of a dying watch — was I burning out? With introspection, I realized the culprit was efficiency. In an effort to achieve maximum efficiency, I was rushing and multitasking, both of which led to mistakes and ultimately created more work for me. All the while, the clocks around me kept ticking.

With regular practice and gentle discipline, I became resigned the idea of never being done and focused on doing. Time spent with patients felt longer; yet, I was rarely running behind. Despite the scattered attention, a concept inseparable from our profession, I began seeing things clearly. To most of us, efficiency is moving faster … but what if moving slower and more deliberately is actually how we create efficiency?

Courtesy of pixy.org (CC0)

Giving time is giving respect.

During my third year of residency, I sat across from each patient, task, and colleague without looking at the clock. During most of residency, I wore a broken watch, which I’d jokingly say was for “for fashion, not function.”

We forged this ethereal phenomenon of time into shackles and bound ourselves forever to its mercy. I’ve broken free, and I am a better doctor for it, I think.