September 19th, 2018

I Was Nearly Kicked Out of the Cafeteria

Scott Hippe, MD

The nature of the crime? Bringing my reusable food container down for meals. I just wanted to avoid the Styrofoam plates and plastic silverware, but the lunch ladies were convinced I was asking for two portions’ worth of side dishes and then only paying for one. I wasn’t, although I admit to once sprinkling cheese from the salad line on my soup [gasp!]. But by that time, I already had a large target painted on my scrubs.

My innocent food container — my small attempt at being mindful of waste — was barred from the cafeteria. The exclusion sent a clear message: Eat on our single-use plates, or do not eat at all. Coming from the same organization that tosses all the contents from its recycling bins into the landfill, I shouldn’t have been surprised.

My cafeteria episode apparently was a big deal in the world of hospital food preparation. One of the cafeteria supervisors sent a message straight to my program director. “Your resident isn’t coloring inside the lines,” was essentially how it read. No matter how trivial the issue, having to explain yourself to your program director is obviously undesirable.

Medical waste is a bigger problem than you might realize

Our medical-industrial complex exerts a significant negative effect on the environment. I am likewise not impressed by the degree to which healthcare contributes to pollution. A 2016 study reported that 9.8% of national greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to the healthcare sector (PLoS One 2016; 11:e0157014). For reference, the study authors explain this amount of emissions supersedes total emissions from all but the thirteen highest-producing countries worldwide.

significant negative effect on the environment. I am likewise not impressed by the degree to which healthcare contributes to pollution. A 2016 study reported that 9.8% of national greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to the healthcare sector (PLoS One 2016; 11:e0157014). For reference, the study authors explain this amount of emissions supersedes total emissions from all but the thirteen highest-producing countries worldwide.

The problem is bigger than just greenhouse gasses. Medical waste takes up space in landfills. Healthcare practices create chemicals that are carcinogenic to humans and toxic to the environment. Particulates generated by hospitals and by production of medical goods are spewed into the air. All of these things have implications to the health of the patients we are supposed to be helping.

What can be done?

With a last name like Hippe, I had best not get too far out in left field on environmental issues. Clearly, some amount of energy has to be devoted to powering our facilities and providing health services. But, “how much energy?” is the important question. In my opinion, we can be doing much better.

There are many levels on which the discussion of environmental health needs to occur, from top tiers of hospital administration down to each individual person. The environmental impact of our activities needs to be highlighted at the organizational level, but lofty aims like this are not readily accessible for the majority of healthcare personnel.

If you find yourself just trying to survive from one day to the next (cough, I’m talking to you, fellow residents, cough) rather than participating in high-level policy discussions, a more realistic place to start might be to decrease your personal waste. Use a coffee mug rather than disposable cups. Stop using sterile gloves for minor skin procedures, because they are associated with no difference in infection rates. (Wash your hands!) Among acceptable surgical techniques, choose the one that employs the least amount of single-use equipment. Save trees by writing concise hand-off reports.

I would be curious to hear other ideas about how you have individually reduced environmental waste, and any inspirational facility-wide policies that have been successful at your institutions.

Lastly, for the truly brave folks out there: Bring your own dish down to the cafeteria — but watch out for the lunch ladies!

September 19th, 2018

Coffee and the State of the Hospital

Ellen Poulose-Redger, MD

I think you can tell a lot about how things are going in a hospital based on the amount of consumption of coffee by its employees. Visit the Starbucks, Au Bon Pain, Roasterie, Einstein Brothers, or whatever coffee shop inhabits square footage in your hospital, and I’d venture to say that you can take the pulse of the hospital. Lots of large coffees to go? It’s either just about shift change and people are rushing into their jobs for the day (or night), or the hospital is bursting at its  seams and everyone is go-go-go. Is someone ordering an Americano? He or she must know that the dregs of the day’s coffee are all that’s left and is instead gambling that a freshly pulled espresso shot is a safer bet. A latte? That lucky person might have a little time to spare and might even sit down to enjoy his or her drink right there instead of hurrying back to the floor/clinic/unit/OR. How about the counter with the milks and sugars — are all the sugar or sweetener packets gone? Must be insanely busy. Milk or — gasp — half-and-half all gone? The shop’s been busy, so much so that they’ve run out of the dairy product within the allowed 2-hour serving time. You see — if you happen to have time to take note of these things — there’s a lot to be observed.

seams and everyone is go-go-go. Is someone ordering an Americano? He or she must know that the dregs of the day’s coffee are all that’s left and is instead gambling that a freshly pulled espresso shot is a safer bet. A latte? That lucky person might have a little time to spare and might even sit down to enjoy his or her drink right there instead of hurrying back to the floor/clinic/unit/OR. How about the counter with the milks and sugars — are all the sugar or sweetener packets gone? Must be insanely busy. Milk or — gasp — half-and-half all gone? The shop’s been busy, so much so that they’ve run out of the dairy product within the allowed 2-hour serving time. You see — if you happen to have time to take note of these things — there’s a lot to be observed.

How much coffee does a residency program go through during a conference? Are the residents burning the candle at both ends while on service? If so, we’ll go through a pot of coffee in 5 minutes as they sit down for afternoon conference. [My co-chiefs and I have carried on the tradition of providing coffee with conference — there is no excuse for sleeping if you have access to caffeine.] Things have been a little bit calmer on the floors and they have a few minutes to decompress? We might need to fire up another pot of coffee after conference, just to give everyone a few more minutes to sit together and chat. How fast are we going through the half-and-half or almond creamer? Are all of the caffeine lovers on service at the same time, or has it been an unusually busy time and everyone’s reaching for a cup during conference? Or perhaps there are days when our “proprietary blend” wasn’t that popular, and most of the coffee went down the drain. (I will never again buy French vanilla coffee. Sorry, everyone.) Even for those who don’t drink coffee, I think just having it there and knowing that someone got there early to set it up and set out the accoutrement for serving shows that we, the nebulous chiefs behind the email account, care. We want our residents to know that yes, the days are long, and the pages are nonstop, but there’s a hug in a cup waiting for them.

How much coffee does a residency program go through during a conference? Are the residents burning the candle at both ends while on service? If so, we’ll go through a pot of coffee in 5 minutes as they sit down for afternoon conference. [My co-chiefs and I have carried on the tradition of providing coffee with conference — there is no excuse for sleeping if you have access to caffeine.] Things have been a little bit calmer on the floors and they have a few minutes to decompress? We might need to fire up another pot of coffee after conference, just to give everyone a few more minutes to sit together and chat. How fast are we going through the half-and-half or almond creamer? Are all of the caffeine lovers on service at the same time, or has it been an unusually busy time and everyone’s reaching for a cup during conference? Or perhaps there are days when our “proprietary blend” wasn’t that popular, and most of the coffee went down the drain. (I will never again buy French vanilla coffee. Sorry, everyone.) Even for those who don’t drink coffee, I think just having it there and knowing that someone got there early to set it up and set out the accoutrement for serving shows that we, the nebulous chiefs behind the email account, care. We want our residents to know that yes, the days are long, and the pages are nonstop, but there’s a hug in a cup waiting for them.

Let’s go back to the coffee shop in the hospital — maybe it’s midafternoon, and a senior resident or fellow or attending has taken an intern there for a quick feedback session. (Please, everyone, do sit down with your learners to give and receive feedback!) Maybe it’s 6:30 am and the senior resident is buying five specialty drinks to celebrate the end of a block with her interns and students. Maybe it’s 9 pm and there’s a couple there, both on call, stealing a few minutes of time with each other before heading back to their respective domains. There is so much to observe in just that little area. That shop is a measure of the pulse of the hospital, if we just look up from our smartphone long enough to see what is going on.

Let’s go back to the coffee shop in the hospital — maybe it’s midafternoon, and a senior resident or fellow or attending has taken an intern there for a quick feedback session. (Please, everyone, do sit down with your learners to give and receive feedback!) Maybe it’s 6:30 am and the senior resident is buying five specialty drinks to celebrate the end of a block with her interns and students. Maybe it’s 9 pm and there’s a couple there, both on call, stealing a few minutes of time with each other before heading back to their respective domains. There is so much to observe in just that little area. That shop is a measure of the pulse of the hospital, if we just look up from our smartphone long enough to see what is going on.

September 12th, 2018

Good Things Take Time

Ashley McMullen, MD

My Patient

The day I met you was early in my second year of Internal Medicine residency. After much of my internship had been spent on arduous inpatient rotations, I was finally ready to lead my own team of young doctors and students on a high-acuity wards service. Yet, in my continuity clinic, I was still fresh, insecure, and naive. The day I met you, your abdomen was swollen, your eyes were yellow, you were drowsy and seemingly apathetic. Years of heavy alcohol use had sclerosed your liver, leading to hepatic disease in its final stages. You were my patient, I was your new primary care doctor — and I didn’t speak your language. We fumbled through the interpreted conversation, hindered by your lethargy, my inexperience, and a 20-minute visit time. We talked about abstinence from alcohol, and we talked about liver transplant. I got you what you needed: diuretics and a paracentesis for your ascites, lactulose and rifaximin to remove the toxins clouding your consciousness, a referral to hepatology to start the process of future transplant evaluation. However, what we both needed was more time.

Our Visits

I would see you in clinic for many more visits in the ensuing months. I would review my check boxes of primary care for cirrhosis – slow disease progression, check; prevention, screening, and treatment for complications, check. All the while, the prospect of transplantation and new life hung in the air like an apparition we could partially see but which remained out of touch. After your second relapse and hospitalization, we met in clinic once again. I remember that your mind was sharp that day. I was running behind, with several patients sitting restlessly in the waiting room, but in that moment, it was just the two of us. In the hour that I didn’t have, we talked about “goals of care.” You told me you wanted a chance at a new liver, I told you about the challenges of both transplant candidacy and surgery, you told me you understood. You told me you wanted to keep pursuing all possible care, you told me how much you missed your family back in Central America. I told you we would stay the course towards transplant, but I also promised you I would do everything within my means to get you back home — even if just to say goodbye. After 13 months as patient-provider, this moment was the first time we actually heard each other. You trusted me. We embraced after that visit and every visit thereafter. But what we both needed was more time.

Transplant Evaluation

In the fall of my last year of residency your kidneys began to fail. The pressure in your portal system was pushing up to 12 liters (over 3 gallons) of ascitic fluid into your peritoneal space. Yet, the frequent paracenteses needed to alleviate your discomfort added more strain to your kidneys that were already starved for perfusion. The rise in your creatinine mirrored a rising MELD score, indicating a looming mortality. By the spring, it was time for an evaluation by the liver transplant team. A day you had been waiting for finally came — you were seen, you were tested — you were deemed not a candidate. The clock was reset — it would be another 6 months of documented sobriety and social support before you would even be reconsidered. The news was devastating for you and your partner. I was away on another inpatient rotation, only peripherally involved via messages that accumulated in my ever-expanding inbox.

You would go on to endure 6 more hospitalizations over the next 3 months, spending more time boxed within four sterile walls than at home in your own bed. You would encounter more than 30 primary and specialty physicians and have multiple goals-of-care conversations, which would at times leave you confused and frustrated. I was losing steam, closing out the end of residency training and preparing to embark on a new journey as chief. You needed me, and I needed more time — time to reflect on your clinical course, time to reconcile your prognosis and goals of care, and time to help you make sense out of the madness.

Going Home

When I saw you in clinic a month ago, you were headed towards yet another acute hospitalization for renal failure. This time, I was present. We met together with the inpatient teams, and I could say to you with confidence, “it’s time to go home.” You were brave and magnanimous — you found humor in a dire situation, and the love shown by you and your devoted partner was inspiring. We met for one last clinic visit after this. You told me you were getting ready to return home to Central America. After we embraced, you winked at me and said, “I’ll see you next time.” Three weeks later, you died at home surrounded by your family. You were out of time.

By Jon Rawlinson (The Long Road Ahead) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), via Wikimedia Commons]

September 4th, 2018

The Power of Intellectual Humility

Scott Hippe, MD

Don’t ever be afraid to say, “I don’t know.”

Those were parting words from one of my physician mentors in medical school. I had asked him for wisdom in making the transition to residency. “In my career, I’ve seen hundreds of physicians who cannot bring themselves to say those words. They are generally the ones who get burnt out. They are the ones that shout at you when you consult them over the phone. They are the ones who leave medicine, one way or another.”

My mentor’s point was to stay intellectually humble. The practical application to clinical medicine is obvious. We’ve all learned about the different types of biases that lead to medical errors and diagnostic misses. As trainees, we have seen physicians who exhibit too much hubris make mistakes.

I am reminded of my mentor’s comments now that July has arrived and a new class of interns has started their training. Their enthusiasm for residency and the pursuit of learning is a breath of fresh air. Along with the enthusiasm has come a multitude of “I don’t knows”:

- “I don’t know where to go when we start in the hospital tomorrow.”

- “I don’t know how the attending likes case presentations.”

- “I don’t know my dictation number.”

- “Can my patient eat?”

- “Can I eat?”

- “What is the best flavor of enema?”

- “Do I need an enema?”

- “She brought her service animal into the hospital, but she didn’t say it was a python.”

- “I don’t know what to do about his pain — he told me he’s allergic to everything but Dilaudid.”

Residency is endlessly humbling, but interacting with interns has shown me how much I have grown as a physician. I can answer all of the questions mentioned above, and even a few more.

One thing is getting harder to say

As my years of residency have gone by, and I have made the transition to senior resident, it has gotten harder to say “I don’t know.” Just like my mentor predicted. Not knowing things on the wards or missing something in clinic stings my pride more now than it did when I was an intern.

As my years of residency have gone by, and I have made the transition to senior resident, it has gotten harder to say “I don’t know.” Just like my mentor predicted. Not knowing things on the wards or missing something in clinic stings my pride more now than it did when I was an intern.

The most common feedback I give to medical students and interns is to be decisive with their plans. This was also the feedback I received on my own medical student rotations. I imagine it is feedback most learners receive. Being a competent clinician requires synthesizing large amounts of data and committing to a plan of action. But it is also possible to take “decisive” too far. A phrase has stuck with me:

“Sometimes wrong, never in doubt.”

A surgeon said this, while preparing to take a patient with abdominal pain to surgery for suspected appendicitis. In this particular instance, appendicitis is exactly what the patient had. It was one of those times to be decisive, and rapidly decisive. But whether through conscious effort or subconscious tendency, we often take “fake it until you make it” too far. We become insecure and isolated clinicians hiding behind façades of confidence. This tendency leads to worse outcomes.

Benefits of intellectual humility

Although “I don’t know” gets harder to say, I am convinced it is one of the most important phrases in the practice of medicine. Embracing the intellectual humility necessary to utter those words has many benefits:

- Encouraging curiosity: this leads to broader differentials and more effective diagnosing

- Counterbalancing “intervention bias”: the tendency of clinicians to do something — anything! — when the best course of action might be to do nothing

- Effective teamwork: clinicians who admit they don’t know everything are more open to the input of others and more likely to see the patient’s big picture.

- Better education: A safe environment, where learners are empowered to disclose their gaps in knowledge, allows educators to address those gaps more effectively.

For newly minted resident physicians, my advice is to embrace “I don’t know.” You will do yourselves and your patients a great service. I will continue to say those three words as well, no matter how sharply it hurts my pride. If any of this inspires passion, positively or negatively, please leave a comment. I am looking forward to communicating with you this year through the Insights blog.

–Scott

August 28th, 2018

So Let’s Chat About Extracurricular Work Activities

Justin Davis, MBBS

Well, we’re finally here. Somehow, an Aussie has sneaked onto a United States-based Chief Resident blog panel dealing with pertinent issues within medicine, and I actually have to think about what to write. (I’m being slightly facetious here, by the way.) So let’s start, shall we?

One of the things that has been on my mind recently, and I think even more so since starting advanced training, is the amount of extraneous work we have to do in this career (read: lifestyle) we call medicine. (Note: for context, for our American audience [and I assume most people who read this will be from the U.S.], in the Land Down Under, physician training requires you to do 3 years of basic training as a medical registrar [internal medicine resident] and sit two exams before applying for specialty training, which we call advanced training.)

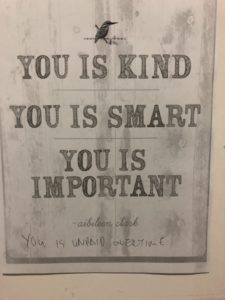

“You is unpaid overtime” — A wiser man than I annotated this poster up in our ressies room. Personally, I think it speaks volumes to the amount of extra work we have to do in our profession.

Now I think it’s important to realise that I’m not talking about unpaid overtime here – that topic has been done to death in previous chief resident posts because it’s a hotly debated topic in several spheres of medical influence. I mean, who amongst us hasn’t done it? From patients being unwell, to clinics being overbooked, to the emergency department somehow having soothsayer-like ability to know exactly when to refer a patient (i.e., half an hour before you think you’re going home for the day, on time for once), to just generally being overworked because that’s what the system demands of you. Rather, what I’m talking about is extra work that we have to do, which isn’t directly related to patient care. And there is a surprisingly large amount of it.

I started to ponder this one evening as I sat in what I affectionately call “the Bungalow” (the name for my office [see included photo], which I’m, in reality, quite appreciative to have this year – it sure beats the old medical registrar office that I used to sit in to do these sorts of things). I think it was a typical sort of day; you know – start work at 8 am, finish at 7 pm (only 1.5 hours late this time), cook dinner, and then return about 8 pm to work until about midnight on things that are not directly related to your clinical role per se, only to wake up at just before 7 am to do it all again. I also realised that I really probably shouldn’t complain – my surgical colleagues work much more ridiculous hours than I do, and our hours are a lot better than what is mandated over there in the U.S. It is also true that medicine is nowhere near unique in having these sorts of extracurricular (I honestly cannot think of a better name for this than that) requirements or unpaid overtime-type issues. But, it still affects us, our partners, our lifestyles in general, and thus I think it remains an important topic to talk about.

“The Bungalow,” complete with my own laptop for music. I feel the $10 plastic plant I got from Kmart adds a class of sophistication to it. Maybe.

What I want to chat about today is the amount of extra activities we find ourselves doing outside of our clinical role, just to progress through the world of medicine. We know why we do them – they’re resume building, and a chance to impress superiors and build important relationships that determine your future eligibility for employment. The work is important and does need to be done, but it’s all done outside of usual working hours because it simply cannot fit into that time (how could it possibly?) and thus ends up being lumped into this misery mire I call extracurricular work activities.

As I’ve noted, it is important work, and it does provide you with important skills that are translatable in clinic and in life, but it does take its toll. I think back on all of the extra stuff I’ve done outside of work hours in this previous 6 months – I’ve organised part of the Royal Australian College of Physicians clinical examination (it’s surprising how long it can take to organise a patient’s complete medical history, medication list, investigations, and imaging requests, when 20+ of them need to be done), prepared morbidity and mortality meetings, prepared several manuscripts for … um, five research papers that are currently active, prepared multiple choice questions for medical students, prepared talks to give to other specialties, and attempted to do a Bland-Altman plot in Microsoft Excel (this was really hard, by the way) to plot 15000 data points of ultrafiltration values. All this is before I do things like my own regular self-directed learning (I think people may have the wrong idea that study stops once your exams are over. It doesn’t. It just becomes more clinically focused and relevant to your chosen specialty.) I can’t see my patient with primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) who has already failed glucocorticoid therapy without having some idea of what to do next now, hey? I’m also attempting to keep up with the latest research/commentary from publications such as the New England Journal of Medicine Journal Watch (sneaky plug here), or just, you know, having a life outside of medicine (I really do enjoy playing video games. Ah, well).

Sometimes, I’d much rather be putting my feet up with Einstein next to me. These moments are rare, so I appreciate them when I have them.

But … we know why we do it. We love this job. I went into nephrology not only because the kidney is awesome and is clearly the best organ (subjective personal opinion), but because my favourite part of working is building up those longitudinal relationships with patients, being with them through a hell of a lot of different circumstances, from their first presentation with renal failure to dialysis to transplant to failing transplant and back to dialysis and so on. And I know that an important part of being a well-rounded clinician is not only knowing the clinical side of things but all the extra work that goes into keeping the grinding wheel of medicine turning – how else could we train future generations? How else could we improve our own practice or systems processes except with an M&M meeting? How else could we improve clinical practice without research into how we can be better? So despite the hours it takes away from my own life, I realise there is a point to all the extracurriculars, and they are an important part of things. Although I do admit it would be nice sometimes to be putting my feet up on the couch and turning on my PlayStation with a nice glass of red wine — as opposed to sitting in the Bungalow, iPhone blaring Mozart’s 21st piano concerto in a really tinny way, and working on some extracurricular thing into the late hours. But hey, would I choose anything else? Realistically… probably not.

“It is not the height of the cliff, but the struggle of the climb that clears my eyes.”

Note: Every blog post I do will be followed by a quote from a particular source for my own amusement which shall remain nameless – there are, of course, bonus points to anyone that can figure out from where I am sourcing these quotes*.

* These bonus points have no monetary or other value. Just my respect.

August 17th, 2018

Things I’ve Learned from My Patients

Ellen Poulose-Redger, MD

I recently completed my internal medicine residency training. Three years, thousands of hours, thousands of patients, thousands of decisions. I certainly learned a lot from the past 3 years: everything from what “HFrEF” means and how to manage it, to treating recurrent C. difficile colitis, to how to share decision-making with patients about whether or not to start anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. Despite the multitude of lessons I have learned from my co-residents, my fellows, my attendings, the nurses, the pharmacists, and everyone else involved in my training, I think that the deepest lessons I’ve learned are from my patients.

Lesson 1:

Earlier this year, a patient gave me a recipe for leg of lamb. He had been fighting a hematologic malignancy for years and had spent the better part of the past 6 months severely neutropenic — and then came in with invasive aspergillosis, which led to emergent and disfiguring surgery. At first, he could laugh about “being a pirate for Halloween” [this was months away from Halloween]. Later, he refused to speak to the team when he realized just how seriously ill he was. There’s nothing worse than watching someone decline like that — and so, I pulled up a chair to the bedside, let his wife have a well-deserved break from being in the room, and asked the patient what he liked to do. He eventually started talking about cooking, which is something I enjoy, too. Naturally, I had to ask him what his “signature dish” was. It was a leg of lamb. As he described how to remove the fascia from the meat, and how to properly spice it, and at what temperature he would roast it, he became more than “the patient with invasive aspergillosis.” I saw a small glimpse of the man who had loved being the center of his family and celebrating with them. When the hours and stresses of residency add up, it’s important to remember to spend time with those we love.

Earlier this year, a patient gave me a recipe for leg of lamb. He had been fighting a hematologic malignancy for years and had spent the better part of the past 6 months severely neutropenic — and then came in with invasive aspergillosis, which led to emergent and disfiguring surgery. At first, he could laugh about “being a pirate for Halloween” [this was months away from Halloween]. Later, he refused to speak to the team when he realized just how seriously ill he was. There’s nothing worse than watching someone decline like that — and so, I pulled up a chair to the bedside, let his wife have a well-deserved break from being in the room, and asked the patient what he liked to do. He eventually started talking about cooking, which is something I enjoy, too. Naturally, I had to ask him what his “signature dish” was. It was a leg of lamb. As he described how to remove the fascia from the meat, and how to properly spice it, and at what temperature he would roast it, he became more than “the patient with invasive aspergillosis.” I saw a small glimpse of the man who had loved being the center of his family and celebrating with them. When the hours and stresses of residency add up, it’s important to remember to spend time with those we love.

Lesson 2:

Some of the things I’ve learned from my patients aren’t as bittersweet. There was another patient, the victim of another drug overdose in the ongoing heroin epidemic, who came under my care last fall. Just as soon as she was remotely stable, she wanted to leave. That instant. So, I went in to talk to her, to see if I could convince her to stay at least a little longer. She had back pain, and if we couldn’t give her pain medications, she was going to go back out on the street and find something that would work. Eventually, she agreed to stay and to try to get help for her addiction. After her estranged daughter showed up to see her, the patient opened up about what had happened to her — after a car accident, she had back pain and had gotten her first prescription for opioids. Years went by with monthly refills, until her physician abruptly cut her off, at which point she turned to the street to get pills, and later, heroin (N Engl J Med 2016; 374:154). Heroin was cheaper; surprisingly cheap, when I asked her how much it cost. Perhaps she was the victim of a well-intentioned effort trying to curb opioid use in this country. Now, though, she wanted to get clean — the condition her daughter set for being able to see her grandchildren. This patient taught me of the importance of looking beyond just “another addict” or “another XYZ” patient, because each of these patients is someone’s parent, partner, child, or friend.

Some of the things I’ve learned from my patients aren’t as bittersweet. There was another patient, the victim of another drug overdose in the ongoing heroin epidemic, who came under my care last fall. Just as soon as she was remotely stable, she wanted to leave. That instant. So, I went in to talk to her, to see if I could convince her to stay at least a little longer. She had back pain, and if we couldn’t give her pain medications, she was going to go back out on the street and find something that would work. Eventually, she agreed to stay and to try to get help for her addiction. After her estranged daughter showed up to see her, the patient opened up about what had happened to her — after a car accident, she had back pain and had gotten her first prescription for opioids. Years went by with monthly refills, until her physician abruptly cut her off, at which point she turned to the street to get pills, and later, heroin (N Engl J Med 2016; 374:154). Heroin was cheaper; surprisingly cheap, when I asked her how much it cost. Perhaps she was the victim of a well-intentioned effort trying to curb opioid use in this country. Now, though, she wanted to get clean — the condition her daughter set for being able to see her grandchildren. This patient taught me of the importance of looking beyond just “another addict” or “another XYZ” patient, because each of these patients is someone’s parent, partner, child, or friend.

Lesson 3:

Several of the things that I’ve learned have been much lighter in nature, too. The retired jeweler in my clinic who gently chastised me for wearing my engagement ring while pulling gloves on and off in clinic. He didn’t want me to accidentally throw away something that’s priceless. The kind older bus driver who recommended places to go for vacation (you were right — Austin was a really fun place to go for a long weekend). The patient who very much misunderstood what I was saying (“I like Boston,” in reference to his Red Sox shirt; not, “I like boxing”) and peppered me with questions about which weight class I liked. The lovely and very chatty patient with whom my attending once left me, as he ducked out of the room, telling her that his resident (me) liked cookies, thus leaving me to debate the merits of thin and crispy vs. thick and chewy cookies for 20 minutes and prompting the patient’s family to show up with bags of cookies for me the next day. These patients taught me to really listen to what people are saying, because these human connections are worth their weight in gold (and chocolate chip cookies).

Several of the things that I’ve learned have been much lighter in nature, too. The retired jeweler in my clinic who gently chastised me for wearing my engagement ring while pulling gloves on and off in clinic. He didn’t want me to accidentally throw away something that’s priceless. The kind older bus driver who recommended places to go for vacation (you were right — Austin was a really fun place to go for a long weekend). The patient who very much misunderstood what I was saying (“I like Boston,” in reference to his Red Sox shirt; not, “I like boxing”) and peppered me with questions about which weight class I liked. The lovely and very chatty patient with whom my attending once left me, as he ducked out of the room, telling her that his resident (me) liked cookies, thus leaving me to debate the merits of thin and crispy vs. thick and chewy cookies for 20 minutes and prompting the patient’s family to show up with bags of cookies for me the next day. These patients taught me to really listen to what people are saying, because these human connections are worth their weight in gold (and chocolate chip cookies).

It can be very difficult when the hours are long, the learning curve is steep, and the patients are sick to remember to learn something every day. Reading books and journals and doing questions is important, but so is learning from our patients. And I am so glad they are willing to teach.

August 17th, 2018

2018-2019 Chief Resident Bloggers

Charleen Hamilton

The staff and editors of NEJM Journal Watch welcome our new panel of Chief Residents! We look forward to their thoughts on medical training and work-life balance for young physicians.

Our 2018-2019 panel includes:

- Ellen Poulose Redger, MD – Ellen is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Stony Brook University Hospital in Stony Brook, New York.

- Justin Davis, MBBS – Justin is a Chief Resident in Medicine at Barwon Health University Hospital Geelong, in Victoria, Australia.

- Cassandra Fritz, MD – Cassandra is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

- Scott Hippe, MD – Scott is a Chief Resident in Family Medicine at the Family Medicine Residency of Idaho in Boise.

- Ashley McMullen, MD – Ashley is an Internal Medicine Chief Resident in Ambulatory Care at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital in San Francisco, California.

We welcome readers’ comments on blog posts.

May 14th, 2018

Bitcoin, Medicine, and More

Karmen Wielunski, DO

Karmen Wielunski, DO, is a 2017-18 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, WI

What’s the big deal about Bitcoin and digital currency? For the past year, my husband (who has a business background) has been enthusiastically researching digital currency. Thus, the terms Bitcoin (BTC) and MaidSafeCoin (MAID) have become commonplace in my household for some time. But, to be honest, I hadn’t been paying much attention to any of it until recently. Don’t get me wrong — it’s not that I don’t listen when my husband talks. Rather, my medically trained mind tends to wander due to an inaptitude for many business and technological concepts.

With all the Bitcoin buzz and a New Year’s resolution to be more up to date on current events, I attempted to become informed. I asked my husband to, once again, break down this whole digital currency thing for me. About 2 minutes into his explanation (I’m sure he could see my mind wandering), he paused and said, “You know what, why don’t I just show you how it works.” And, with that, I was buying (a fraction of) a Bitcoin.

I started by creating an account on Coinbase. This was easy and only required verification of my email address and phone number. I then linked it to my bank account. With a click of a button, I was the proud owner of 0.0021 Bitcoin (worth US$25). Actually, I had to wait a few days for the transaction to process, but it was less complicated than I imagined. By creating an account, I also acquired a public address that consists of a long string of numbers and letters (for example, mine is 166ZUjHuWRGBFm71irtEXLhJRKCv4JooqM). While I won’t be committing this to memory anytime soon, I learned that the public address allows for easy transfer of digital payments from one party to another.

I started by creating an account on Coinbase. This was easy and only required verification of my email address and phone number. I then linked it to my bank account. With a click of a button, I was the proud owner of 0.0021 Bitcoin (worth US$25). Actually, I had to wait a few days for the transaction to process, but it was less complicated than I imagined. By creating an account, I also acquired a public address that consists of a long string of numbers and letters (for example, mine is 166ZUjHuWRGBFm71irtEXLhJRKCv4JooqM). While I won’t be committing this to memory anytime soon, I learned that the public address allows for easy transfer of digital payments from one party to another.

A Frightening Revelation

With my newly acquired (though, admittedly still minimal) knowledge, I wondered how Bitcoin might affect healthcare. It only took about 30 seconds of internet research to realize that Bitcoin and digital currency are already very much affecting healthcare. I read an article that detailed a cyberattack on the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS). During the attack, hackers created an electronic lockdown that affected the NHS and then demanded a Bitcoin ransom to release it (N Engl J Med 2017; 377:409).

Another article detailed a very recent cyberattack on a hospital in Indiana that targeted more than 1400 files. The hospital paid 4 Bitcoins (about $47,000) to hackers to regain access to their files (Health IT News 2018 Jan 16; [e-pub]). The reports of these attacks went on and on — institutions in Texas, California, and Kentucky are all recent victims. Each story detailed some combination of patient record and computer access involvement, and many involved Bitcoin ransom requests.

Another article detailed a very recent cyberattack on a hospital in Indiana that targeted more than 1400 files. The hospital paid 4 Bitcoins (about $47,000) to hackers to regain access to their files (Health IT News 2018 Jan 16; [e-pub]). The reports of these attacks went on and on — institutions in Texas, California, and Kentucky are all recent victims. Each story detailed some combination of patient record and computer access involvement, and many involved Bitcoin ransom requests.

WHAT? This is a big deal! My simple quest to learn about a trendy form of currency led me to recognize a very serious threat to healthcare system security. As I continued to read through more accounts of recent cyberattacks, I felt embarrassed about my obliviousness up to this point. I worried about the seemingly routine nature of these attacks. Are we all just sitting ducks waiting for our healthcare information to be breached?

Hope For The Future

With a sense of urgency, I again consulted my husband. “Did you know this was happening?” I asked. He was excited about my continued interest in the topic and began catching me up. It turns out other people are (understandably!) worried about this, too. Many companies are attempting to create programs using Blockchain — the technology upon which Bitcoin is based — to improve data security.

One company called MaidSafe, he explained, is taking an entirely different and exciting approach to solving this problem. They are currently developing a new technology using datachains to create a SAFEnetwork which is, essentially, a decentralized, anonymous internet. The network data is encrypted, broken into pieces, and stored across many locations, making it anonymous and secure beyond existing systems. The live version could possibly launch in 2018 and holds great promise for countless applications including the safe keeping of healthcare information.

One company called MaidSafe, he explained, is taking an entirely different and exciting approach to solving this problem. They are currently developing a new technology using datachains to create a SAFEnetwork which is, essentially, a decentralized, anonymous internet. The network data is encrypted, broken into pieces, and stored across many locations, making it anonymous and secure beyond existing systems. The live version could possibly launch in 2018 and holds great promise for countless applications including the safe keeping of healthcare information.

As previously noted, my knowledge of technology is limited at best, and I don’t claim to be an expert on this topic. The above explanations are likely drastically oversimplified, but I feel it is important to discuss the concepts and what is being done to combat this threat to healthcare security. In the meantime, I still feel like a sitting duck. However, it’s encouraging that people are working to come up with a solution, and hopefully one will be available soon.

February 8th, 2018

Doctoring in Lipstick

Cassie Shaw, MD

Cassie Shaw, MD, is a 2017-18 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Saint Louis University Hospital in Saint Louis, MO

Why do I feel weird wearing lipstick in the hospital? Why do I have to announce myself as a doctor to gain respect from patients and other members of the hospital staff? In my short time as a physician, I have yet to find the answer to these questions, but they seem to lie in my set of XX chromosomes. As in all other areas of life as a female, being a doctor comes with a different set of rules than that of my male colleagues. These rules are never mentioned or taught, but they are apparent the first time you step foot into the role. We aren’t men, but we need to fit in with them and act like them — but we also have to act like women, in the right ways, of course. Confused yet? Same. Let’s consider some questions about the abilities of a physician who’s also a woman.

The photos in this post are dedicated to my female colleagues who are all creating their own mold as physicians. Brit, Physical Medicine and Rehab; Ellen, Internal Medicine and Michaela, Emergency Medicine

Question 1

Can she be a leader? Can she provide medical care and make critical decisions? Yes, with tremendous effort. I quickly learned to state my role clearly when walking into a room. “Hello, Mr. X, I am your doctor.” Of course, it’s inevitable that a patient, nurse, or family member will ask to talk to the “real doctor,” or say “oh, I’m not used to a lady doctor,” or reference a male colleague as “the doctor.” Even worse is when staff members double-check with a male in the room to see if my plan was the medical plan for the patient. Meanwhile, none of my male colleagues have ever been assumed to be any healthcare professional other than a doctor.

Question 2

Can a woman who is physician also be feminine? If we do not wear makeup, we are asked if we are sick or having bad day. If we do wear lipstick or a skirt, negative assumptions are made about our IQ and our abilities as a doctor. Not only is our appearance a careful balance, but so are our interactions. A woman cannot use even the slightest tone of forcefulness when advocating for her patient without being labeled as that 5-letter word that begins with a b: bossy. In fact, if we aren’t sugary sweet, we are quickly written off as being angry, rude, or a another 5-letter word that begins with a b. (Use your imagination.) Meanwhile, when my male colleagues do the same, it causes a flurry of action to complete the task they’ve asked to be done without a single mention of his mood, how his day must be going, or his hormones.

Question 3

Can women work as physicians and have a home life? Yes, but to many, your home life is more important than your career life. Ultimately, society doesn’t judge us by our accomplishments at the bedside, but on those within the home. Am I married? Have I had children? (Shouldn’t the real question be, why does it matter? I spent 23 years completing the rigorous education and training required to obtain the job I dreamed of and that accomplishment is swiftly diminished by these two questions.) I have a huge fear of moving forward with having children because I wonder what might happen to my career. The life of a physician is far from flexible. My partner (and the would-be baby-daddy in this hypothetical scenario) is also a physician, but you can have one guess as to who society would expect to give up a portion of their career in order to raise a child. Or worse, if I did not cut back at work and hired help instead, I would be that terrible mother whose children are “raised by a nanny.” Again, not a word would be said about my partner’s work load as a physician who is male.

Okay, if it wasn’t obvious, I’m being facetious when asking and answering these questions. Women can be, and are, accomplished, astute clinicians, who are leaders in their fields and at the bedside, all while wearing whatever makeup they choose and maintaining whatever work-life balance they desire. However, these are all challenges that they face daily. I attribute many of these challenges to the way women entered the role of a physician. Like all of our roles in male-dominated fields, women before me fought to obtain foothold here. They weren’t welcomed as physicians in their own right, so they squeezed themselves as closely as they could into the mold of a physician created by their male counterparts. It’s obvious, though, that we aren’t made to fit that mold. We have our own mold, but that does not preclude us from being excellent physicians.

Recently, as I reflected on all of these experiences, I decided to make a change. I started small: I wore lipstick while on service. Initially, it was uncomfortable and awkward but when I assisted my intern with her first lumbar puncture while rocking my sassy pink lipstick, it was a tiny, but empowering, salute to my femininity. I had both worlds exactly as I wanted them. I wasn’t blending into my male-dominated surroundings. I was forming my own mold. It wasn’t just about lipstick anymore.

So, to end this blog, I’m looking right at my co-physicians who also happen to be women. Remember, we aren’t female physicians or “lady doctors.” There is no need for that gender-defining adjective. We are physicians and, ladies, we are crushing it. We are balancing things our male counterparts would never dare to try and can never understand. However, we are still doing it all within the mold created by men. It’s time to break out of that mold. It’s time to show off our power and stop blending. It’s time to do things our own way.

November 21st, 2017

Thoughts on Stigma

David Herman, MD

David Herman, MD, is a 2017-18 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Southern California / LAC+USC Medicine Center in Los Angeles

“What are we legally able to do? I don’t want to say the ‘quarantine’ word, but I guess I just said it. […] What would you advise, or are there any methods, legally, that we could do that would curtail the spread?”

These sentences were spoken by Betty Price, an American politician with a seat in the Georgia House of Representatives for the 48th district. Her questions were posed to Dr. Pascale Wortley, director of the HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Surveillance Section at the Georgia Department of Public Health, during a videotaped discussion regarding barriers to access of adequate healthcare for patients with HIV. Although she later stated that these remarks were taken out of context, in 2017, the uttering of these phrases, marked by what would appear to many to be discrimination and prejudice, should at the very least warrant swift and continual condemnation and, truthfully, should motivate constituents to question whether leadership proposing this type of strategy is the type that they deserve. This is especially true in a state where the rate of HIV diagnoses per 100,000 people in 2015 was second only to the District of Columbia, according to the CDC, and a state that demonstrates a need for true reform in HIV care.

What is all the more devastating about these remarks is that Representative Price is not only a politician, but, more importantly to the purpose of this piece, a physician trained in anesthesiology. She practiced her chosen field for more than 20 years in Roswell and Marietta, GA, serving on multiple boards, including the Medical Association of Atlanta and the Medical Association of Georgia. Moreover, she is a past president of the American Medical Women’s Association in Atlanta and a recipient of the President’s Award from the Medical Association of Atlanta and a Phenomenal Women of North Fulton Award. In short, she is an exceptionally educated and truly accomplished woman and a physician of considerable influence within and beyond her community.

Thus, the implication from her, a respected doctor, that those infected with HIV should, by the very nature of their infection, be considered for quarantine, despite all that we know today about the nature of this disease, is incredibly alarming. It is a prime example of what drives fear among individuals affected by this disease. Comments like this are what attach stigma to this diagnosis. And for many, it is a contributing factor to keeping them from investigating their status or seeking appropriate care.

Thus, the implication from her, a respected doctor, that those infected with HIV should, by the very nature of their infection, be considered for quarantine, despite all that we know today about the nature of this disease, is incredibly alarming. It is a prime example of what drives fear among individuals affected by this disease. Comments like this are what attach stigma to this diagnosis. And for many, it is a contributing factor to keeping them from investigating their status or seeking appropriate care.

The comments by Dr. Price are just an example of how stigma persists. Defined, stigma is a mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance. It runs rampant throughout medicine and extends significantly beyond HIV and AIDS. Every time we apply our own sense of negative judgment to a disease or condition, we implicate those who may be suffering from it. Judgment often stems from our own prejudices against certain populations or behaviors. Societal conceptions of intravenous drug users or those who engage in sex work, for instance, can color our perception of hepatitis C or sexually transmitted infections and imbue those diseases with negative connotations. People at risk for contracting them may avoid evaluation or treatment rather than suffer the discrimination associated with diagnosis or follow-up. And this prejudice can expose itself in many ways: It can flow like an avalanche through the middle of a House of Representatives inquiry on barriers to care, or it can leak out in elevator conversations when cracking jokes about a patient’s new diagnosis of syphilis. Either way, it can have a rippling effect on those that hear it and tighten stigma’s hold.

This seems equally as evident in the discussion of mental health, a topic certainly on the minds of many as reforms to healthcare are currently being proposed. The way we deal with mental health in this country and around the world is a major problem. Not only is access to care among those with mental health disorders grossly inadequate, but the social stigma associated with a diagnosis or treatment of a mental health disease can further debilitate individuals already suffering from debilitating diseases. A survey of more than 1700 adults in the U.K. published in 2000 found that the most commonly held beliefs regarding mental health problems were that people who suffer from them are dangerous and that many mental health problems are self-inflicted. The authors concluded that these beliefs, among others they identified in their study, contributed to social isolation, distress, and difficulty in employment (Crisp AH et al. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177:4). Though we can certainly acknowledge that mental health disease can of course lead to aggressive and violent behavior in some, the generalization that mental health disorders equal danger is a troubling stereotype to apply to an entire population, especially one that needs to be embraced with care and not pushed away by fear. Similarly, the implication that mental disease is self-inflicted is at its very core insulting to those inflicted, erecting walls around those in need.

This is why stigma is so devastating; not only does stigmatization affect the way patients seek evaluation and engage in treatment, but it affects the way doctors engage and support patients in need. When this relates to mental health, for instance, it demonizes an individual who suffers internally from psychiatric disease and further isolates him or her. When this relates to transmissible disease it results in improper identification of those who require treatment and can facilitate the passage of infection between individuals. In general, it worsens outcomes and impedes solutions.

This is why stigma is so devastating; not only does stigmatization affect the way patients seek evaluation and engage in treatment, but it affects the way doctors engage and support patients in need. When this relates to mental health, for instance, it demonizes an individual who suffers internally from psychiatric disease and further isolates him or her. When this relates to transmissible disease it results in improper identification of those who require treatment and can facilitate the passage of infection between individuals. In general, it worsens outcomes and impedes solutions.

So, as doctors on the front line of this issue, what can we do? It is incumbent upon us as a profession to take care with how we conduct ourselves and communicate. When we allow our own prejudices to infiltrate our communications to patients or others, we do them a drastic disservice. Because the short answer to Dr. Price’s question is not to isolate or quarantine but to test adults as per CDC Guidelines for HIV infection and to plug them into effective and supportive care as indicated. And yet by saying what she said, she has already sewed her seeds, unearthed her own prejudice, and further affected the way in which a vulnerable population views the medical profession, preventing us, in my opinion, from truly being able to find an answer to the problem.

The specter of stigmatization is held tightly within our society and will not easily be shaken. As such, we need to look long and hard within ourselves and ask whether and how we are contributing to it. We have a duty to our patients and much of that is not allowing our own bias to affect the work that we do and the care that we deliver. This is as important in our treatments as in our communications. Ultimately, educating ourselves on various conditions and confronting our own views on them, advocating for the rights of our patients, supporting those patients through their diagnoses and treatments, working to normalize illness by taking it out of the social construct from which discrimination arises, and treating a disease for what it is — simply a disease and not a commentary or judgment on the individual with it — these are some strategies to employ. But the words that we use in our discussions are just as important. Hopefully, as we continue as a profession to discuss these issues, we will continue to grow to the benefit of our patients. And until such a time as stigma no longer exists, it is also important to continue to call out words such as Dr. Price’s and to mind our own.