August 28th, 2018

So Let’s Chat About Extracurricular Work Activities

Justin Davis, MBBS

Well, we’re finally here. Somehow, an Aussie has sneaked onto a United States-based Chief Resident blog panel dealing with pertinent issues within medicine, and I actually have to think about what to write. (I’m being slightly facetious here, by the way.) So let’s start, shall we?

One of the things that has been on my mind recently, and I think even more so since starting advanced training, is the amount of extraneous work we have to do in this career (read: lifestyle) we call medicine. (Note: for context, for our American audience [and I assume most people who read this will be from the U.S.], in the Land Down Under, physician training requires you to do 3 years of basic training as a medical registrar [internal medicine resident] and sit two exams before applying for specialty training, which we call advanced training.)

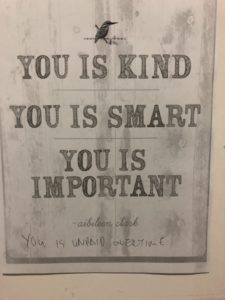

“You is unpaid overtime” — A wiser man than I annotated this poster up in our ressies room. Personally, I think it speaks volumes to the amount of extra work we have to do in our profession.

Now I think it’s important to realise that I’m not talking about unpaid overtime here – that topic has been done to death in previous chief resident posts because it’s a hotly debated topic in several spheres of medical influence. I mean, who amongst us hasn’t done it? From patients being unwell, to clinics being overbooked, to the emergency department somehow having soothsayer-like ability to know exactly when to refer a patient (i.e., half an hour before you think you’re going home for the day, on time for once), to just generally being overworked because that’s what the system demands of you. Rather, what I’m talking about is extra work that we have to do, which isn’t directly related to patient care. And there is a surprisingly large amount of it.

I started to ponder this one evening as I sat in what I affectionately call “the Bungalow” (the name for my office [see included photo], which I’m, in reality, quite appreciative to have this year – it sure beats the old medical registrar office that I used to sit in to do these sorts of things). I think it was a typical sort of day; you know – start work at 8 am, finish at 7 pm (only 1.5 hours late this time), cook dinner, and then return about 8 pm to work until about midnight on things that are not directly related to your clinical role per se, only to wake up at just before 7 am to do it all again. I also realised that I really probably shouldn’t complain – my surgical colleagues work much more ridiculous hours than I do, and our hours are a lot better than what is mandated over there in the U.S. It is also true that medicine is nowhere near unique in having these sorts of extracurricular (I honestly cannot think of a better name for this than that) requirements or unpaid overtime-type issues. But, it still affects us, our partners, our lifestyles in general, and thus I think it remains an important topic to talk about.

“The Bungalow,” complete with my own laptop for music. I feel the $10 plastic plant I got from Kmart adds a class of sophistication to it. Maybe.

What I want to chat about today is the amount of extra activities we find ourselves doing outside of our clinical role, just to progress through the world of medicine. We know why we do them – they’re resume building, and a chance to impress superiors and build important relationships that determine your future eligibility for employment. The work is important and does need to be done, but it’s all done outside of usual working hours because it simply cannot fit into that time (how could it possibly?) and thus ends up being lumped into this misery mire I call extracurricular work activities.

As I’ve noted, it is important work, and it does provide you with important skills that are translatable in clinic and in life, but it does take its toll. I think back on all of the extra stuff I’ve done outside of work hours in this previous 6 months – I’ve organised part of the Royal Australian College of Physicians clinical examination (it’s surprising how long it can take to organise a patient’s complete medical history, medication list, investigations, and imaging requests, when 20+ of them need to be done), prepared morbidity and mortality meetings, prepared several manuscripts for … um, five research papers that are currently active, prepared multiple choice questions for medical students, prepared talks to give to other specialties, and attempted to do a Bland-Altman plot in Microsoft Excel (this was really hard, by the way) to plot 15000 data points of ultrafiltration values. All this is before I do things like my own regular self-directed learning (I think people may have the wrong idea that study stops once your exams are over. It doesn’t. It just becomes more clinically focused and relevant to your chosen specialty.) I can’t see my patient with primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) who has already failed glucocorticoid therapy without having some idea of what to do next now, hey? I’m also attempting to keep up with the latest research/commentary from publications such as the New England Journal of Medicine Journal Watch (sneaky plug here), or just, you know, having a life outside of medicine (I really do enjoy playing video games. Ah, well).

Sometimes, I’d much rather be putting my feet up with Einstein next to me. These moments are rare, so I appreciate them when I have them.

But … we know why we do it. We love this job. I went into nephrology not only because the kidney is awesome and is clearly the best organ (subjective personal opinion), but because my favourite part of working is building up those longitudinal relationships with patients, being with them through a hell of a lot of different circumstances, from their first presentation with renal failure to dialysis to transplant to failing transplant and back to dialysis and so on. And I know that an important part of being a well-rounded clinician is not only knowing the clinical side of things but all the extra work that goes into keeping the grinding wheel of medicine turning – how else could we train future generations? How else could we improve our own practice or systems processes except with an M&M meeting? How else could we improve clinical practice without research into how we can be better? So despite the hours it takes away from my own life, I realise there is a point to all the extracurriculars, and they are an important part of things. Although I do admit it would be nice sometimes to be putting my feet up on the couch and turning on my PlayStation with a nice glass of red wine — as opposed to sitting in the Bungalow, iPhone blaring Mozart’s 21st piano concerto in a really tinny way, and working on some extracurricular thing into the late hours. But hey, would I choose anything else? Realistically… probably not.

“It is not the height of the cliff, but the struggle of the climb that clears my eyes.”

Note: Every blog post I do will be followed by a quote from a particular source for my own amusement which shall remain nameless – there are, of course, bonus points to anyone that can figure out from where I am sourcing these quotes*.

* These bonus points have no monetary or other value. Just my respect.

Medicine will eat your time and justify by telling you you are a better Dr. beware positive and negative coping skills. Good sleep habits, exercise, eat healthy, talk to “God”, do something for another person out of the goodness of your heart. VS : drugs, alcohol, sex, gambling, food over consumption. Dr heal thy self!

Very enjoyable reading. Thank you

Hi!!! Great reading. Very nicely writen. It reflects many of our daily activity quite honestly.

Pretty sure that quote is from Destiny!