February 2nd, 2017

From Leogane to Longwood: How Different Are Our Patients?

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

When I worked in family medicine, I considered my practice to have two very distinct patient populations — the pediatric population I served from their birth to adolescence and the adult population — each with a very different set of needs. Now that my practice has changed and I care exclusively for patients over age 18, I am focused on a more limited set of diagnoses and issues. Returning from volunteer work doing patient care in Haiti a few weeks ago, I thought about the Haitians and my U.S. patients: Are these now the dual populations that I serve? Are these two different worlds to be straddled? Or are they more similar than they seem?

I believe that the differences appeared starker to me when I first arrived at Toussaint L’Overture Airport in March 2011. The landscape and population needs —one year after the massive earthquake that is still a defining point of Haitian history — were like nothing I had ever seen.

I was raised in a small New England town and have lived my entire adult life in Boston. However, as I spend more time in Haiti, the edges continue to soften, the lines to blur. And during this year’s trip, it seemed clear to me that there are more commonalities than disparities between my Haitian patients and those who visit me in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston.

One clear example is a clinical visit involving a mother and child. Working in Brockton, I saw many patients for their first newborn visits and then for subsequent well-child checks or urgent concerns. In Haiti, due to the sporadic nature of our clinics, I cannot provide the continuity of care that American children receive. However, mothers there have the same urgent care questions, expressing their concerns over an earache, a loss of appetite, or a fever that leaves a child sweating through their pajamas. They want to know: Are their kids getting what they need? Are they as mothers providing the right interventions? What is “normal”? The American mother and the Haitian mother care equally about their children, regardless of differences in health care and other resources. They share a core desire to understand and help their children. And they both need and respond to the reassurance that a healthcare provider can give, the reassurance that is, 99% of the time, the most important part of an interaction with a patient.

Discussions with adult patients also share common themes, like work-related health effects; outdoor laborers have dry eyes, those who do physical work are more apt to complain about musculoskeletal pain, etc. Age and involvement of family can affect a patient’s ability to obtain care, in both Haiti and Boston. A patient with no one nearby to offer care sometimes presents when a concerned neighbor or friend finally brings them to a visit. Often, these patients are more likely to have mental health issues as a result of their isolation. Although social barriers to health may be present on a wider scale in one place versus another, they are present in both places.

Finally, the truth remains that the anatomy and pathophysiology of disease in one human are largely the same as in every other human. Even as we advance our understanding of the effects of ancestry and genetics on health, by and large, our assessments and interventions are the same because one patient does not vary so significantly from another. Each blood pressure we measure in Leogane is done the same way as one measured in Boston. A diabetic person is more prone to heal slowly from an infection in either city. A severe stroke has the same debilitating consequences in either place.

In recent days, we have heard much on the news about the differences between people both within and outside the borders of our country. From my unique and privileged position as a healthcare provider, it seems to me that now is a good time to be reminded of the basic human commonalities we all share; we really are more the same than we are different, from Leogane to Longwood and around the world.

January 26th, 2017

Can Medical Professionals Ask Patients About Guns?

Alexandra Godfrey, BSc PT, MS PA-C

A student recently asked me if clinicians can talk to patients about gun ownership and safety. Her question triggered my month-long search for data to provide a solid evidence-based response.

Alas, my research did not unearth such an answer. But I did find endless writing that discussed this increasingly contentious question in terms of rights, ideology, law, politics, ethics, and medicine.

I realized that if we are to have an honest discussion about the relevance of gun safety to medical practice, it is essential to study the major conundrums that have caused polarization among patients, providers, state legislatures, and medical organizations. The American Medical Association (AMA), the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society of Adolescent Medicine are examples of organizations that encourage clinicians to counsel patients about gun safety; they oppose legislative action that limits or obstructs such discussions. Florida and Montana are examples of states that have passed legislation that limits questions by physicians about gun ownership, a stance supported by gun lobby groups.

The Issues

Can we legitimately call gun violence an epidemic like polio, measles, and HIV?

According to gun lobby groups, gun violence is not an epidemic. Epidemics refer to diseases; more specifically, to surges in infectious disease. The use of the word epidemic is a misnomer aimed at creating an emotional response. Some dismiss such language as rhetoric and hyperbole, lacking in caliber and sincerity.

Undeniably, epidemic in the past was limited to infectious diseases. Today, the scope is much broader: an epidemic refers to a condition, disease, or undesirable phenomenon that affects a disproportionately large number of the population. Such new definitions can be seen in dictionaries like Merriam-Webster and the Oxford English dictionary: “the practice had reached epidemic proportions” or “an epidemic of crime.” Given this change, it is reasonable to refer to gun violence as an epidemic.

Undeniably, epidemic in the past was limited to infectious diseases. Today, the scope is much broader: an epidemic refers to a condition, disease, or undesirable phenomenon that affects a disproportionately large number of the population. Such new definitions can be seen in dictionaries like Merriam-Webster and the Oxford English dictionary: “the practice had reached epidemic proportions” or “an epidemic of crime.” Given this change, it is reasonable to refer to gun violence as an epidemic.

If we look at an epidemic as “a surge” or disproportionate increase, such terminology becomes questionable. Firearm mortality rates have generally remained stable over the past 30 years. The agency defines an epidemic as “a recent increase in amount or virulence of [an] agent.” I am not sure we can say gun violence is virulent, although it may feel so at times. If we consider gun violence in terms of type, then we can see America has had a stark increase in mass shootings — namely an epidemic. Precision in the language of medicine matters.

What about the data?

According to the CDC, the total number of firearm-related deaths in 2015 was 36,252; of these, 2824 affected individuals aged 0-19 years. Mortality data can be subdivided into suicide, homicide, legal, and unintentional. Whether or not you consider these numbers to be disproportionately large is somewhat subjective: how many deaths from firearms are too many? Gun lobby groups cite that few of these deaths are accidental; some are related to gang violence or are suicides, but this surely leaves us making value judgments according to intent, mechanism, or ideology. Are deaths from suicide any less preventable or tragic?

How do we define a “public health issue,” and are guns a threat to public health?

Gun groups contend gun violence is not a public health issue, as most injuries and deaths occur from the negligent or malicious use of a firearm. It is neither a disease nor a medical problem. Thus, questions regarding gun control and measures to ensure public safety should be under the jurisdiction of the legal system. The National Rifle Association sees the public health approach as an attempt by medical organizations at gun control.

Public health is defined by the CDC Foundation as “the science of  protecting and improving the health of families and communities through promotion of healthy lifestyles, research for disease and injury prevention.” Given the number of injuries caused by firearms, it is legitimate to consider gun violence a public health issue. Merriam-Webster also includes “preventive medicine” as part of its definition of public health. Talking to patients about gun ownership and safety is preventive medicine.

protecting and improving the health of families and communities through promotion of healthy lifestyles, research for disease and injury prevention.” Given the number of injuries caused by firearms, it is legitimate to consider gun violence a public health issue. Merriam-Webster also includes “preventive medicine” as part of its definition of public health. Talking to patients about gun ownership and safety is preventive medicine.

Are questions about gun ownership an invasion of privacy or violation of the Second Amendment?

Gun lobby groups and gun owners see questions about ownership of firearms as a value judgment. Some worry that documentation of gun ownership in medical records might be accessed by the federal government to create databases. Others consider clinician questions about guns as a challenge to their Second Amendment rights. They cite fears that the information will be used to discriminate against gun owners or discourage gun ownership. They consider these discussions to be an underhanded means of promoting an anti-gun political agenda.

Medical organizations argue that personal questions are an essential part of medical practice inherent to the clinician-patient relationship. Pediatricians ask about guns just as they would car seats, swimming pool fences, and safe storage of noxious chemicals. Patients have the right to decline to answer such questions. Additionally, the AMA suggests that “physician gag laws” violate the First Amendment rights of clinicians.

Reconciling rights and ideology with the Hippocratic Oath (duty to protect) is difficult. In response to my student’s question: yes, medical professionals can ask about gun ownership and safety, but they need to be attentive to state legislation that sets parameters for such questions and cognizant of the patient’s right not to answer. A reasonable approach is to ask such questions in situations where gun ownership and gun safety are relevant to the context of the encounter: a well-child check, gun-related injuries, or when patients are at risk of suicide or homicide.

January 19th, 2017

Interview with Jon Harris, PA-C — Health Care for the Homeless

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

I met Jon Harris, PA-C, during his days as a PA student at Northeastern University and was immediately impressed. He excelled in my course, and I knew that he was destined to be an impactful clinician. He previously had graduated from Columbia University with a degree in environmental sciences and spent several years working in the nonprofit, nonmedical community. On a friend’s advice, he started volunteering as an EMT in rural Vermont and quickly found a love for medicine. Jon now works for Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP) and makes a difference everyday in a medically challenging population.

BB: So, how did you become interested in BHCHP?

JH: Actually, I originally thought I wanted to go into oncology, and then I did a rotation during PA school at a state hospital for low-income patients and I loved it. I found the same type of challenging medicine that I sought with oncology, but in a unique population. I found that I connected well with the patients and felt like this was the work I wanted to do. I didn’t even know BHCHP existed but was introduced to the organization by a generous PA who helped me during my job search. It’s fascinating medicine, but more importantly, it is a venue where close relationships with patients make a difference. I find it satisfying to tune into the person in front of me and recognize if they need something like humor, time for silence, or just brutal honesty.

BB: Sounds like you really love the work, what’s your favorite part of the job?

JH: I really do. I love this job because it connects me to the beauty of another human being. Homeless people may appear disheveled on the street or arrive intoxicated for multiple visits to the emergency room, and these sorts of things unfortunately create distance between them and their medical providers. I have found, however, that when we speak to each other in the exam room and let pretenses and guardedness dissolve, patients communicate to me that they want the same things I do: loving relationships and a fulfilling life. Not only do we share similar dreams, but we also have the same shortcomings.

BB: You clearly have a passion for working with this population, but I’m sure — like with most jobs — there are challenges. What’s the most challenging aspect of working with the homeless population?

JH: Yes, I have definitely explored and discovered the boundaries of my compassion doing this work. For example, I took care of a young pregnant woman who was also addicted to multiple substances. She would repeatedly arrive at our clinic high, requiring us to send her to the OB/GYN clinic that specializes in pregnant women with addiction. Thinking of the injury she was repeatedly causing her unborn child made me furious. I forced myself to remember her awful childhood filled with its own abuse and addiction. This works sometimes, but not often. In the end, I recognize that with some patients I need to accept the sinking feeling of not knowing where to find empathy and do my best to treat the human being in front of me.

BB: That must be tough. Do you see illnesses on a regular basis in this population that most other clinicians don’t see that often?

JH: The team sees chronic illness at a greater severity than many other clinicians in other health care settings. For example, many of my diabetic primary care patients have a terribly high hemoglobin A1c with multiple complications: peripheral neuropathy, chronic kidney disease, limb amputations, etc. Because our patients often have an extensive problem list, we also face the challenge of managing heavy polypharmacy.

In addition to what I’ve already mentioned, we also see a lot of HIV, hepatitis C, cirrhosis, and addiction. These are usually related to alcoholism and IV drug use.

BB: Do you only see these patients in the clinic or urgent care?

I frequently am asked if we only provide urgent care to the homeless population. We actually provide primary care in quite unique settings. PAs work in shelters. Our workspace is literally a clinic embedded within a shelter. We have a Street Team that does rounds throughout the streets of Boston providing care to patients who prefer to stay on the street instead of the shelter, as well as a Family Team that works with homeless families.

BHCHP also has a 104-bed inpatient respite facility, the Barbara McInnis House, which is staffed mostly by PAs and NPs. We admit patients who are too sick to be on the street but not sick enough to be admitted to a hospital, such as someone with pneumonia or requiring perioperative care. I spend one day a week working at the Pine Street Inn, a shelter in Boston’s South End, and the remaining three days at the Barbara McInnis House.

BB: Wow! You have a lot of diversity in your job. What is one piece of advice that you’d give to someone looking to transition into working with the homeless population?

JH: I once asked a patient to give his advice on working with homeless people to a new provider I was orienting at BHCHP. His eloquent response best answers this question:

“I’ve been an alcoholic since my father gave me liquor when I was a kid. Please don’t think you’re going to cure my alcoholism. You’re not. Instead, I would really appreciate you taking the time to listen to me.”

BB: That’s incredible advice. Thank you for taking the time to chat with me and sharing what you do. I bet you have inspired some people to look into health care for the homeless.

January 11th, 2017

On the Front Lines of Regional Medicine

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN practices pediatric cardiovascular care across the Pacific Northwest.

Being of Alaska Native decent, my desire to practice medicine in Alaska was only natural. However, once I started venturing out into the large geographical region my institution serves, I realized there is nothing scarier than sending a fragile patient home to some of these isolated areas.

A large part of my job is to collaborate with regional providers. With my limited knowledge on the subject, I decided to ask exactly what it’s like to provide regional specialty care to children across a vast area of land.

In speaking with Dr. Jim Christiansen, pediatric cardiologist in Anchorage, I learned a great deal. With only 4857 miles of paved roads in Alaska, access to clinics is typically a combination of many modes of transportation. Think planes, bush planes, boats, and snow machines. His practice, which he shares with one other cardiologist, travels to 11 different practice sites throughout the state. Most of these visits rely on air travel.

Dr. Christiansen says a fair number of his patients rely exclusively on mail-order pharmacies to get their medications, which makes for some creative thinking when weather or other natural phenomena interrupt mail delivery. In fact, there was a time a patient ran out of Coumadin only to be rescued by his school principal who was also taking the medication.

Often times, the choice of surgical procedure (e.g., mechanical vs. bioprosthetic valve) will depend on geographical location and accessibility to appropriate INR monitoring. This proves to be especially challenging when a patient requires Lovenox, as there are only two labs within the state that manage low-molecular-weight heparin levels. In the Bethel census area, there is only one pharmacy serving an area the size of Oregon

Roughly 70% of Alaska’s physicians reside in only two cities (Anchorage and Fairbanks). In general, subspecialty care is restricted to these locations. Sometimes villages are staffed by a health aide for care. Pediatric specialties are especially limiting — for example, Dr. Matthew Hirschfeld, director of maternal-child medicine at Alaska Native Medical Center, travels to Nome approximately once every other month. Up until about 4 months ago, he was the only pediatrician who traveled to the region. Nome serves as the central hub for 19 surrounding villages. The total population for Nome and these villages is about 10,000, with about 40% being younger than 19 years old.

Roughly 70% of Alaska’s physicians reside in only two cities (Anchorage and Fairbanks). In general, subspecialty care is restricted to these locations. Sometimes villages are staffed by a health aide for care. Pediatric specialties are especially limiting — for example, Dr. Matthew Hirschfeld, director of maternal-child medicine at Alaska Native Medical Center, travels to Nome approximately once every other month. Up until about 4 months ago, he was the only pediatrician who traveled to the region. Nome serves as the central hub for 19 surrounding villages. The total population for Nome and these villages is about 10,000, with about 40% being younger than 19 years old.

Being one of the only pediatricians who travels to Nome, Dr. Hirschfeld and his case manager follow roughly 300-350 kids who either have chronic medical conditions or who have been referred for consultation.

Alaska is not the only state with limited resources. I have worked with areas in central Washington and Montana, informing local hospitals and fire departments of fragile patients. I have gone as far as providing education for each specific patient. As one can imagine, with HIPPA laws being what they are, this gets to be tricky.

Dr. Jeremy Archer, pediatric cardiologist in Billings, Montana, has similar concerns. Not only is he a cardiologist, he has a master’s degree in health outcomes and policy. So he is quite passionate regarding the topic of Regional Medicine. Dr. Archer has found a calling in creating quality-improvement pathways for fragile patients. He believes the same level of care should be given regardless of patient location. He has created risk-stratification guidelines for his patients and is very open-ended with families when discussing outcomes and location to care. He occasionally advises patients that it would be in their best interest to relocate to bigger cities, despite the financial and social challenges for their families. He feels honesty regarding outcomes is best.

Dr. Jeremy Archer, pediatric cardiologist in Billings, Montana, has similar concerns. Not only is he a cardiologist, he has a master’s degree in health outcomes and policy. So he is quite passionate regarding the topic of Regional Medicine. Dr. Archer has found a calling in creating quality-improvement pathways for fragile patients. He believes the same level of care should be given regardless of patient location. He has created risk-stratification guidelines for his patients and is very open-ended with families when discussing outcomes and location to care. He occasionally advises patients that it would be in their best interest to relocate to bigger cities, despite the financial and social challenges for their families. He feels honesty regarding outcomes is best.

In addition to providing cardiology care to his patients, Dr. Archer assumes the care of gastrostomy tubes and other noncardiac needs. It is often too difficult to find specialty care specific to his patients needs in such areas.

Knowing these limitations, my job is to help patients prepare for discharge with the goal being home disposition. However, some of our patients are so fragile, and live in such distant villages, that we have started to collaborate with local hospitals to transport patients back to the institution they came from. For example, in Anchorage, before sending patients home, we transport them to the Alaska Native Medical Center, which then arranges travel back to their medical hub, where a pediatrician sees them before transport all the way home. Best case scenario: at each phase in these transfers, provider-to-provider communication occurs to formally hand off each patient. The hope of this interaction is to decrease the number of fragile patients discharged without adequate resources, thereby lessening the subsequent bouncebacks to the hospital or even subsequent deaths.

I ask myself, in our ever-changing healthcare system, is it irresponsible to leave these patients in such need? Or is what we are doing — bringing more and more awareness to regional medicine — enough?

January 8th, 2017

7 Medical Terms to Ditch in 2017

Harrison Reed, PA-C

Your new diet plan might fail. That daily planner might collect dust on the corner of your desk. The gym membership gifted by a well-intentioned (but not-so-subtle) cousin might go unused. But fear not. You can still resolve to make 2017 just a little bit better than last year. And it starts by cleaning out the clutter of some terminology that must retire.

The following list includes terms that in some way hamper, impede, degrade, misinform, or otherwise gunk-up communication in the healthcare setting. If you’re rolling your eyes and thinking to yourself, “oh great, a grammar snob is going to spend an entire blog picking over the semantics of my charts,” you’re right. But you already clicked on the link so you might as well keep reading.

Besides, you might like it.

“Liver Function Tests” or “LFTs”- People often use the phrase “liver function tests” (or “LFTs”) to refer collectively to aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminases (ALT). Although this shortcut is ubiquitous in healthcare, we have inexplicably agreed to accept a complete misnomer. Generally speaking, the AST/ALT values do not describe liver function as much as they represent enzymes released in the setting of hepatocellular destruction or death. It’s like calling your favorite cocktail “liver function sauce.”

In fact, there is a longer list of labs that better represent the metabolic and synthetic function of the liver that often seem to escape the traditional umbrella of “LFTs.” While I’m sure most clinicians understand this concept, many still enjoy the convenience of the erroneous term. The fix is simple: use “transaminases.”

“Regular Rate and Rhythm” or “RRR”- Another common shortcut that places convenience over accuracy, you’ll find this abbreviation in the physical exam section of many progress notes. Even some large, commercial electronic medical record services place the “triple Rs” as a one-click option. You’ve probably already guessed my beef: while a rhythm can be regular, a rate cannot. Use “regular” to describe your rhythms and your toothpaste. Call your rate “normal.”

“Regular Rate and Rhythm” or “RRR”- Another common shortcut that places convenience over accuracy, you’ll find this abbreviation in the physical exam section of many progress notes. Even some large, commercial electronic medical record services place the “triple Rs” as a one-click option. You’ve probably already guessed my beef: while a rhythm can be regular, a rate cannot. Use “regular” to describe your rhythms and your toothpaste. Call your rate “normal.”

“Nauseous” vs. “Nauseated”– I’m the first one to admit my own guilt here, but it’s important to know this distinction when you’re confronted by a real grammar geek. The primary definition of “nauseous” is actually “causing nausea.” So during morning sign-out when you say your patient “became nauseous overnight,” someone might think he made his nurse puke. But I bet you really meant the patient experienced nausea or was nauseated.

By now, you might think this blog is pretty nauseous, too.

“AAM”/ “AAF”- When I read this abbreviation in the first line of a note, I assume it means “African-American male” or “African-American female.” The truth is, I don’t really know. There should be a separate debate about whether or not race/ethnicity/skin tone should be included in the first line of a note. But this term has plenty of other reasons to get the boot. There’s the confusion factor: it could just as easily mean Asian-American male, Armenian-American female, or any other combination of words based on your geographic perspective. And then there’s the respect factor: my patients are “ladies” and “gentlemen” (or something else, if they prefer). Leave the gonadal descriptors to the biologists.

“Little Old Lady” or “LOL”- I assume this is a relic of the pre-texting era. But since I have read this in a real present-day chart, I feel obligated to include it. There’s an image this phrase conjures: your own grandmother set down her knitting needles and her tea and drove herself to the hospital. It attaches the kind of bias that makes even the best clinicians miss the diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal or a sexually transmitted infection. Plus, in the abbreviated form, it sounds like you had a good laugh in the middle of writing your note. This vernacular belongs in its own retirement home.

The entire Glasgow Coma Scale (“GCS”) – Like the VCR, the floppy disc, and most technology from the 1970s, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) has outlived its utility. The GCS was designed to communicate neurologic status in trauma patients and has since crept into the lives of nearly every other specialty.

And what’s not to love? In a single number you can communicate a wealth of information about your patient’s mental status.

Except it doesn’t work. A GCS of 10, for instance, tells you that something is wrong but nothing more. It could be a confused patient with quadriplegia. Or it could be a patient who followed your every motor command but refused to open his eyes or speak until you knuckled his sternum. Besides, were those “motor responses” bilateral and equal or was there something focal to report? And did his eyes open spontaneously because he was seizing?

The fact is, any score other than a perfect 15 or a rock bottom 3 requires a longer explanation. And that’s a conversation you could have without attaching a silly, confusing number.

“Midlevel”- The letters behind my name mean I am contractually obligated to mention this once per year. The collective term for PAs and NPs (and CRNAs and nurse-midwives) is not “midlevel.” Pick your favorite reason as discussed by every blog on the Internet: an outdated hierarchy of medicine, the false idea that PAs somehow bridge the nursing and medical worlds, the implication of substandard care.

But I offer an appeal to your pragmatic side. “PA/NP” is only five characters when typed. “Midlevel” is eight. So if you won’t ditch the term for your colleagues, do it to save space on Twitter.

Scour these terms from your vocabulary and leave a comment with your own medical term to ditch in 2017.

December 22nd, 2016

A Lesson in Hospitality

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

A couple of weeks ago I was wandering through the centuries-old walled city of Assisi in the central region of Italy. I was lost in the quaintness of the cobblestone streets, the piazzas, the fountains … and then curiously interested in the oldest thing I had ever seen up until that point (having not yet reached our destination of Rome, the Eternal City) — the Temple of Minerva erected in the 1st century BC. I started thinking to myself — looking at all the beautiful white stone, the view of the city in the valley from our perch atop a hill — if nursing doesn’t work out for me, I could definitely move to Assisi. And then I heard our tour guide, Giuseppe, start chatting about the town hospital. So much for my vacation mentality.

He told the story of a building that was located in close proximity to a monastery, a convent,  and a cathedral. My friend Giuseppe — a farmer who tended to olive trees and goats most days of the week but on others was a secret historical expert tending to groups of tourists tromping through his father’s hometown — began to explain the hospital of the 15th century. He told us of the hospital as a resting place for those who were suffering, a refuge for those with few resources — the poor, the hungry, the sick. They came to this place to be cared for, to rest, to receive what the monks and nuns all those centuries ago had to give — they came to receive hospitality.

and a cathedral. My friend Giuseppe — a farmer who tended to olive trees and goats most days of the week but on others was a secret historical expert tending to groups of tourists tromping through his father’s hometown — began to explain the hospital of the 15th century. He told us of the hospital as a resting place for those who were suffering, a refuge for those with few resources — the poor, the hungry, the sick. They came to this place to be cared for, to rest, to receive what the monks and nuns all those centuries ago had to give — they came to receive hospitality.

I think I had an existential revelation in that moment (one of many to be fair): Who could go to Venice and not be mesmerized? Who could gaze at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and not be moved to feel something bigger than themselves? But also this one, a revelation standing in front of a hospital built in the 1400s, on a tiny street in the small town of Assisi, thousands of miles from home: I could stand in that place finally appreciating the meaning behind the place where I spend 40 (or let’s be honest, more like 60) hours of my week. A hospital, the place where one sought hospitality.

Seven hundred years later, I don’t think it’s just the etymology of the word hospital that gives it the same meaning as that small white stone building in Italy. The same spirit lives inside the doors of Brigham and Women’s Hospital — and I have the privilege to see it every day. We may not be wearing habits or robes (scrubs are more practical and comfortable), and life is generally much more secular here, but we are providing the same basic services for people from all walks of life that the clergy of the 15th century set out to offer. Staff from all disciplines (registrars, nurses, florists, providers, valets) are essentially hosts for our patients. We listen to them when they tell us what type of aid they are seeking, we help determine what they need, and we do our best to provide it. So while over the course of many years, our specialties, education, titles, technology, and so much else has changed, it still comes down to this place of hospitality, a place for those in need to seek care and others being present to provide it. It is certainly a reminder for this provider to be the best host I can be.

Hospitality — the friendly and generous reception and entertainment of guests, visitors, or strangers

Hospital — a charitable institution for the needy, aged, infirm, or young

December 14th, 2016

Welcome to the Theatre … the Operating Theatre

Megan Tetlow, PA-C

Megan Tetlow, PA-C, is from Fort Myers, Florida, now working in Sheffield, England, as part of the National Physician Associate Expansion Program. She practices in gynecologic oncology and is a guest blogger for In Practice.

The OR here in the U.K. is called the theatre, or operating theatre. If you say OR, you’ll likely get a bemused expression, meaning you’re speaking like an actor from Grey’s Anatomy again. One of my supervising physicians here relayed a story to me from a British mentor of his who had practiced in the U.S. during his training. The doctor had been notified to come to the hospital for an emergency surgery. The OR nurse called him to make sure he was on his way, and he said pleasantly, “Oh no problem, I’m just on my way to the theatre now” — to which the nurse replied in panic, “You’re going to the theater?! We need you in the hospital!” George Bernard Shaw was right: we really are two nations divided by a common language. The differences in this area go beyond semantics and can be quite interesting … and a bit challenging. Today I would like to highlight some of the differences I’ve noticed in working in a British theatre versus an American OR.

Start Time of 8:30 am

Yes, that’s an 8. Theatre lists start a little later here. My attending physicians were particularly aghast when I said that in the U.S., the first case is at 7:30 and we round on everyone on the floor (or ward, if you want to be British) prior to that. We do finish later here, so it all evens out. I didn’t mention that there are no tea breaks in the U.S. either, which would certainly have sounded even more horrifying.

Full Team Brief

This is a practice that was adopted somewhat recently by National Health Service theatres. In NHS hospitals, before the start of the day, the OR team meets for a team brief. The whole team — including the attending surgeon, anesthesiologist (or anaesthetist, again if you want to be properly British), residents, circulating nurses, scrub techs, students, etc. — all meet in a circle. The group then proceeds to introduce themselves and go through a checklist that outlines the cases for the day, reviews any surgical/anesthetic concerns, enumerates any potential patient or safety concerns, and outlines the work flow for the day. I think the full team brief is a great way to make sure everyone on the team is on the same page and also drives home the message that avoiding errors and keeping patients safe is everyone’s responsibility.

Self-Service Dressing

It was my first day working as a PA in the theatre in the U.K. As I walked back to scrub in, one of my attending docs yelled to me, “By the way, it’s self-service here!” I must have looked really confused (quite common during my adjustment to working in the U.K.), because he explained further that here, everyone gowns and gloves themselves (even the most senior attending surgeons). At which point my other doctor exclaimed, “What?! They actually dress you in America? I thought that was just on television!” I’m happy to say that my self-gowning and -gloving time has improved dramatically since my first day.

yelled to me, “By the way, it’s self-service here!” I must have looked really confused (quite common during my adjustment to working in the U.K.), because he explained further that here, everyone gowns and gloves themselves (even the most senior attending surgeons). At which point my other doctor exclaimed, “What?! They actually dress you in America? I thought that was just on television!” I’m happy to say that my self-gowning and -gloving time has improved dramatically since my first day.

Learning the Language

After my first foray into the theatre, it was clear that if I was going to survive there, I would need to learn a whole new set of British surgical lingo. The language differences in the OR here run the gamut from surgical equipment (a  Bovie in the U.S. = handheld diathermy in the U.K.) to surgical techniques (a “flash” in the U.S. — the technique where the assistant slowly releases a clamp just enough that the surgeon can push down the knot on the suture and then regrabs = an “ease-and-squeeze” in the U.K.) to even basic anatomy (the area posterior to the uterus that we would know as the posterior cul-de-sac = the Pouch of Douglas in the U.K. Maybe they don’t have cul-de-sacs in general here? I should find out).

Bovie in the U.S. = handheld diathermy in the U.K.) to surgical techniques (a “flash” in the U.S. — the technique where the assistant slowly releases a clamp just enough that the surgeon can push down the knot on the suture and then regrabs = an “ease-and-squeeze” in the U.K.) to even basic anatomy (the area posterior to the uterus that we would know as the posterior cul-de-sac = the Pouch of Douglas in the U.K. Maybe they don’t have cul-de-sacs in general here? I should find out).

Lacking a British to American English medical and surgical dictionary, the best I can do is learn as much as I can as often as I can — which come to think of it is probably a good motto for any healthcare professional, regardless of your location or geographic vernacular.

December 8th, 2016

Intracranial Aneurysms for the Non-Neurosurgical Provider: Primer Series, Part 3

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

In part 3 of this primer series, I will discuss a basic overview of monitoring patients who are not undergoing treatment for intracranial aneurysm as well as potential treatment options for those who are. (See part 1 for a summary of natural history studies and part 2 for information on patient risk factors.)

Many times the decision is made not to intervene because the modifiable and/or non-modifiable factors make the risk of intervention greater than the risk of not intervening. In these cases, we continue to follow the patient with imaging. The type of scan, the intervals of imaging, and duration that we follow patients vary based on several factors such as the patient’s age and the size, morphology, and progression of the aneurysm. If monitoring is the appropriate course and if the first image was of good quality, then we will typically see the patient in clinic in 6 months with an MRA or CTA. If an MRA will provide the quality that we need, it is the preferred method of following a patient because there is no radiation. If nothing has changed with the patient’s risk factors and imaging also remains unchanged, we push the next clinic appointment and imaging to one year, then see the patient again in two years. If we observe a change in the aneurysm, we are very likely to offer treatment.

If treatment is the appropriate next step, there are essentially two paths that we discuss with patients: open surgical clipping and endovascular treatment. From the patient’s perspective, there are advantages and disadvantages to both. Within the endovascular path of treatment there are several choices, described below.

Open Surgery: Craniotomy for Clipping

General Advantages:

- With a well-placed clip, the aneurysm is cured.

- Less follow-up imaging is required as compared to endovascular treatment (our team does a postoperative diagnostic angiogram while the patient is still in house to ensure that blood flow to the aneurysm has been cut off and then a follow up CTA in 1-2 years).

General Disadvantages:

- Longer recovery for the patient as compared to endovascular treatment

- Incision line scar (note: the scar is usually hidden in the hairline)

- A bad haircut – This is surgeon specific. Most commonly a small strip of hair is shaved along the incision line, but it could range from no shave to a large strip.

- Mild discomfort postoperatively with facial swelling and when chewing (the temporal muscle is cut in order to gain craniotomy access – most often the temporal muscle heals, but is tender for the first few weeks after surgery)

- Not appropriate for all aneurysms

Endovascular Treatment Options:

General advantages

- Faster recovery time — Generally our patients are discharged on postoperative day 2.

- No large incision

- Minimal postoperative pain

General disadvantages

- Requires more postoperative imaging as compared to clipping – most patients are followed for at least 2 years because if recanalization of the aneurysm occurs, it generally happens in the first 2 years. Imaging occurs at the following intervals post procedure: 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years.

- Not appropriate for all aneurysms

Coiling (+/- Stenting)

Specific Advantages:

- The oldest and probably most common method of endovascular treatment of aneurysms

Specific Disadvantages:

- Not ideal for treating wide-neck aneurysm without additional equipment — If an aneurysm has a wide neck, a stent must be used in addition to the coils. The stent requires the patient to be on dual antiplatelet therapy 5 days prior to the procedure at our institution and approximately 6 weeks postprocedure. This can be problematic for patients already on anticoagulation for cardiac or DVT reasons. Triple agents increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding significantly and we try to avoid it in our patients.

- Permanent mass effect — If a patient presents to clinic with cranial nerve symptoms secondary to a large aneurysm pressing on the nerve, adding coils will secure the aneurysm, but it will also likely worsen the nerve deficit.

- Not ideal for treating oddly shaped aneurysm because it is difficult to get the coils in all dimensions

Liquid Embolic Agents

Specific Advantages:

- Due to their fluidity, liquid embolic agents such as Onyx or n-BCA are a good option for oddly shaped aneurysm that may be otherwise difficult technically to coil.

Specific Disadvantages:

- Similar to coiling, liquid embolic causes permanent mass effect.

- Generally not the first choice to treat uncomplicated aneurysm

Pipeline Flow Diversion Stent

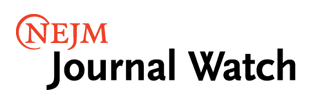

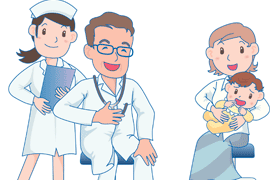

Image shows the remodeling of parent ICA vessel before and after pipeline placement. Arrow points to where the aneurysm used to be.

A braided cylindrical mesh stent designed to divert flow to blind pouches.

Specific Advantages:

- Unlike coiling and liquid embolic agents, the pipeline flow diversion stent is laid across the neck of the aneurysm and does not require intra-aneurysm catheter work.

- Also, unlike the two previous options, the pipeline flow diversion stent causes stagnation of blood within the aneurysm, causing it to shrink, scar down, and remodel the vessel around the stent. This removes the issue of mass effect.

Specific Disadvantages:

- Pipeline also requires patients to be on dual antiplatelet therapy — clopidogrel (Plavix) 75 mg and aspirin 325 mg — for 5 days prior to the procedure and 6 months postprocedure. This makes it a difficult treatment choice for patients with ruptured aneurysms and those already on anticoagulants, as mentioned above.

WEB (in clinical trial)

The WEB is a globular intrasaccular device made of nitinol mesh that combines theory behind coiling and pipeline flow diversion.

Specific Advantages:

- Faster than coiling because it is a single deployment

- Does not require dual antiplatelet therapy as per the group running the trial (the Sequent)

- Due to the unique design that combines flow diversion, it can be used with aneurysms that may be oddly shaped (which, as mentioned above, was a disadvantage of coiling alone).

Specific Disadvantages:

- Not FDA approved, nor is it available in the U.S market except under clinical trial guidelines (the WEB has been available in Europe for 6 years)

- Permanent mass effect

Conclusion

If a patient needs aneurysm treatment, he or she has several options, though not every type of treatment is an option for every patient. Patient factors such as age and comorbidities and aneurysm factors such as size, location, and morphology may limit options. It is worth mentioning that when referring patients for aneurysm treatment, you should consider sending them to: 1) a neurosurgeon trained in both open and endovascular techniques, or: 2) two providers – a neurosurgeon traditionally trained in only open techniques and a second provider trained in endovascular techniques. This ensures that your patient has options. Some aneurysms could be treated with relatively low risk in either an open or endovascular fashion, but if they only see a provider that does one but not both, you may be limiting your patient’s options without realizing it.

A special thank you to my team for some of the images utilized in this posting: Dr. Ali Aziz-Sultan, Chief of Vascular and Endovascular Neurosurgery – Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Dr. Nirav Patel, Cerebrovascular & Skull-Base Neurosurgeon – Brigham & Women’s Hospital

Disclosure: I was a sub-investigator under Dr. Ali Aziz-Sultan at Brigham & Women’s Hospital on Sequent Medical’s WEB trial. The trial has concluded and I did not/will not receive any personal compensation for the clinical trial.

November 30th, 2016

A Colicky Conundrum

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN

After my first baby, I always said that my second one was bound to be clingy, colicky, and skinny, as my first daughter was fat and happy. Aside from a few bursts of crying between 4 and 6 weeks of age, she was the perfect baby.

My second daughter is now 3.5 months old. When she was about 3 weeks old, I first noticed that no matter what I did, she cried, unless she was sleeping. Initially I had a pretty good attitude about it. I kept thinking she would outgrow it and life would move on. But then she started screaming herself hoarse and arching her back. I found myself getting nutty. I was very frustrated and doubting myself as a mom. I kept asking myself: What is going on? What am I doing wrong? Why won’t my baby stop crying? To make matters worse, she needed me so much that I felt like I was ignoring my two-year-old, who said to me more than once, “Baby sister is okay, Mama, I need you right now.” Or, “Baby sister cries all the time, Mama, what is wrong? When can I have you?” To say that I felt guilty is an understatement. There I sat — hormonal, postpartum, and torn, finding myself needing to choose between an infant and a toddler. That’s when I realized that this is how postpartum depression develops and, worse, how shaken baby syndrome happens. (Disclaimer: I never felt like shaking my baby).

Multiple people offered their advice. My dad said to lay her tummy on my tummy, my sister said to sing to her, a friend said to let her cry and to walk away to get relief. My mom said to just hold her and rock or bounce her. I tried it all and nothing helped. I started her on over-the-counter anti-gas drops hoping that would do the trick. Nothing. She was relentless in her crying. Thankfully, my husband shared a lot of the care responsibilities with me.

Multiple people offered their advice. My dad said to lay her tummy on my tummy, my sister said to sing to her, a friend said to let her cry and to walk away to get relief. My mom said to just hold her and rock or bounce her. I tried it all and nothing helped. I started her on over-the-counter anti-gas drops hoping that would do the trick. Nothing. She was relentless in her crying. Thankfully, my husband shared a lot of the care responsibilities with me.

At our two-month well-child checkup, my provider asked about crying. I said, yes, my baby cries. ALL. THE. TIME. She asked when, and I said all day every day. I explained that we really don’t get relief unless she is sleeping, that even when I hold her, she is fussy and crying. Our pediatrician suggested that we start ranitidine for reflux. I instantly said no, arguing that reflux is over-diagnosed and that I didn’t want to be ‘that’ mom whose infant with colic was being treated for reflux. I also argued that as a relatively big baby, she didn’t seem to meet the criteria for reflux. Shouldn’t she be failing to thrive if she had reflux? The pediatrician laughed and explained that infant colic follows the rule of threes: crying for 3 hours a day, 3 days a week, and for more than 3 weeks. She also explained that a lot of big babies have reflux and keep eating to soothe the pain, causing a vicious cycle of eating and crying. Reluctantly, I started the meds. Within days, her periods of crying lessened and she stopped arching her back. I felt horrible that I didn’t address the issue sooner. Now she still cries, but not nearly as much, and my mental health has improved.

There is nothing more frustrating to a new mom than a baby who cries ALL the time. Moms need assurance that this is normal (and fairly common, affecting 10%–40% of children), empathy that it sucks, and validation that they are doing nothing wrong. My pediatrician knew I was at my wit’s end and needed a solution. I am so grateful that she took the time to ask, listen, and counsel me. Not once did she make me feel like a bad mom.

Being a pediatric provider, this experience opened my eyes to a few things. First, I am guilty of dismissing a baby with colic. This showed me how wrong I was. I know now that from my experiences as both a mom and a provider, I must take the extra time to sit with parents of newborn patients and listen to what is going on. I will provide the support needed to assure a mother that she is doing everything right. I will sympathize that hearing your baby cry all day every day is hard. Validating a mother and/or father is so important and can be incredibly therapeutic. I urge my colleagues to do the same. The time we spend on therapeutic communication might prevent or lessen colic-associated short-term depression and anxiety in stressed or exhausted parents, and might even save a parent from causing harm such as shaken baby syndrome.

November 25th, 2016

A Word of Precaution

Harrison Reed, PA-C

When I try to explain the art of medicine to people –family, friends, strangers on airplanes—I scare them a little. You see, I sometimes say, in medicine there is often not a right or wrong answer. Two clinicians, both competent, might approach the same problem in two very different ways. We don’t refer to one great cookbook of medicine for every problem; our actions are a combination of knowledge, training, experience, preference, and environmental influences.

I understand why that concept might frighten laypeople. They imagine medicine as a magic curtain behind which centuries of flawless science coalesce to a complete consensus. To think that two renowned hospitals or two decorated surgeons might take opposite approaches to the same ailment sounds a lot like tossing a coin.

But variation in practice is unavoidable. Our collective pool of medical and scientific knowledge expands and morphs at breakneck speed and the implementation of that knowledge often lags behind. We try to balance the early adoption of sound evidence with the threat of overreacting to every signal that emerges from the cloud of theory and research. And each of these decisions are complicated by a long list of biases.

But variation in practice is unavoidable. Our collective pool of medical and scientific knowledge expands and morphs at breakneck speed and the implementation of that knowledge often lags behind. We try to balance the early adoption of sound evidence with the threat of overreacting to every signal that emerges from the cloud of theory and research. And each of these decisions are complicated by a long list of biases.

In medicine, we have another tendency that is often left off the list of sneaky cognitive effects: a bias toward action. It makes sense to have this. After all, patients come to us with a problem on which they expect us to act. We have a massive and growing tool belt and a general agreement that it’s better to fail in heroic attempts than in passive observation. Want a simple test of this theory? Next time someone asks you for your patient care plan say “nothing” and watch the scoffs and eye-rolls begin.

Of course, experienced clinicians know that doing nothing is sometimes a fantastic choice. We don’t work on motorcycle engines. The human body comes with its own plan. We are just the co-pilots.

So how do we balance these concepts: the ever-evolving scientific data pool, our propensity toward action, and the knowledge that sometimes the best course is no action at all? The answer may rest within the precautionary principle.![]()

The precautionary principle states that if an action has the potential to cause harm, in the absence of scientific consensus, the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those taking the action. In other words: before we do something, it is our responsibility to prove that it is safe.

It seems like a pretty basic concept and you might think we already incorporate this into our practice of medicine. Often, we do. Drugs undergo a lengthy approval process, new procedures are piloted before they become the standard of care, and randomized controlled trials are the mainstay of evidence-based practice.

But the history of medicine and public health is also riddled with instances of throwing precaution to the wind. The dangers of radiation exposure, for example, had plenty of early whistleblowers, including famous ones like Thomas Edison, and we still took many decades to appreciate the fallout. Asbestos was flagged as an “evil,” harmful material by British factory inspectors in 1898 but it was stuffed into our schools and homes almost 100 years later. And where was the precautionary principle when thalidomide sat on pharmacy shelves despite crippling thousands of infants? Or when the fatal effects of the synthetic estrogen DES, prescribed despite a lack of good evidence of its efficacy, finally came to light? Or when Vioxx hit the market?

It may seem like this is a principle only relevant to environmental safety advocates and federal regulators. But every day we have a chance to apply to the precautionary principle. Perhaps you had an (asymptomatic, non-hemorrhagic) anemic patient whose hemoglobin nudged just below 7.0. Did you order a unit of blood, a treatment with plausible and documented harms, despite any real proof that 7.0 is safer than 6.8?

We could have all used more of the precautionary principle before the recent explosion of opioid prescribing led to epidemic levels of heroin and narcotic drug abuse. If every legislator, drug manufacturer, and prescriber had accepted that burden of proving safety before taking action, thousands of lives might have been saved.

Of course, the very nature of precaution means that at some point we can’t just look back on mistakes of the past. We must consider what we are doing right now. And what we are about to do. We must remember that a bias toward action comes with an obligation to ensure we take the safest course.

And that sometimes restraint is the most heroic action of all.