December 8th, 2017

Trafficking: Taking Care of Sarah

Alexandra Godfrey, BSc PT, MS PA-C

Sarah

The neighbors called the police when they heard screaming. An officer discovered her hiding in a closet in a trailer. In the emergency room bay, I find Sarah naked except for a T-shirt. Her legs are drawn up, arms wrapped around her knees, head down. She looks severely malnourished, and her teeth are broken and decayed. Bites, bruises and stab wounds cover her body. There are strangulation marks on her neck. There are track marks on her skin. Someone has been stubbing out cigarettes on her arms.

Sarah doesn’t know her location, the time or the date. She has no documentation: no driver’s license, bank card, nothing. When I ask her whom she lives with in the trailer, she is too terrified to answer.

Sarah is 18 years old.

Trafficking is the recruiting, transporting, harboring or receiving of a person through force in order to exploit her or him for prostitution, forced labor or slavery.

According to the U.S. State Department, 600,000 to 800,000 people are trafficked across international borders every year. Many more are never identified. And in the U.S., the Polaris Project has received over 30,000 reports of trafficking through its national hotline in the past eight years, and many more are at risk. Sarah is one of these children.

Victims can be anybody, and it is too easy to dismiss them as addicts or prostitutes. Trafficking is a violation of basic human rights and crosses socioeconomic class and gender barriers. A teenaged boy in my ER was kicked out by his alcoholic father, and a friendly stranger offered to help him. Before he knew it, he was cut off from family and friends, and forced to take drugs and trade sex for shelter.

How Do You Recognize a Victim of Sex Trafficking?

There are warning signs. Sarah’s presentation for care was delayed—she was not brought to the hospital when she was first injured. Other warning signs I learned about include: inappropriate or lacking clothing, signs of malnourishment, fear or distrust, reluctance to speak, and lack of identifying documents.

Physical health indicators include: bruising, burns, cuts, broken teeth, memory loss, insomnia, weight loss, malnutrition, loss of appetite, STDs, genital trauma, substance abuse and somatic complaints.

Victims might have mental health issues: suicidal thoughts, hypervigilance, anxiety, signs of withdrawal, dissociation and detachment, difficulty engaging in social interactions and feelings of shame or guilt.

The trafficker might be with the victim. This person might be overly controlling, or the patient might appear submissive in his or her presence. I separate the patient from such people and ask simple questions: Can you tell me about the person who brought you here? Do you feel pressured to trade sex for money or anything else? Has anyone threatened you? Are you able to leave your room or house whenever you want?

By recognizing the signs of sex trafficking and increasing our awareness in the healthcare community, I think healthcare professionals can help. We might prevent further abuse and protect victims this way. I have been talking with psychiatric access nurses, social services, and shelters in an effort to collate the resources available in our ERs.

By recognizing the signs of sex trafficking and increasing our awareness in the healthcare community, I think healthcare professionals can help. We might prevent further abuse and protect victims this way. I have been talking with psychiatric access nurses, social services, and shelters in an effort to collate the resources available in our ERs.

Sarah

At sixteen, Sarah was homeless until she met John, who said he would take care of her. He took her to a house where other women lived, where weed, cocaine and crystal meth littered the tables. Sarah was forced into sex that first day. At gunpoint, she was forced to take drugs. John gave her lingerie but little else: no toothbrush, no bed, not even tampons. She was forced into sex with every man John brought to her. And they were many. She was told she couldn’t leave, as she owed John money.

It takes me a while to earn Sarah’s trust and for her to tell me her story. I reassure her that her safety is our first priority and remind her that the police won’t prosecute her for possession or prostitution—a legitimate fear for victims of trafficking. I tell her that she won’t return to the trailer. We find her safe shelter and resources for rebuilding her life.

Sarah’s plight shocks me. She was held captive for at least six months in a trailer between a brothel house and an apartment building right on my route to work. I realize that sex trafficking is happening here where I live. I have driven past it every day. I wonder how many more around me live like Sarah.

As healthcare professionals, we cannot correct this problem alone, nor take away a victim’s trauma. But we can do more, and my hope is that through increased awareness, we can help more victims.

Some Useful Resources:

https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/

https://polarisproject.org/

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/trafficking.html

November 15th, 2017

Nurse Practitioner by Day, Mama by Night (or All the Time)

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN practices pediatric cardiovascular care across the Pacific Northwest.

As I first ventured into motherhood, I was often asked by my sisters, friends, and colleagues how I did it. Not only how I was able to be a mom while also working full-time as a regional nurse practitioner, in a role that involves frequent travel, but how I made it look so easy. To this, I laughed. I may be able to make it work, but only when a well-organized schedule falls perfectly into place.

Having two small kids with a third on the way and a husband who not only teaches full time but is a high school football coach, I rely heavily on our full-time daycare schedule. When daycare is closed or one of my girls is sick, it’s a stark reminder of how much we need it for our lives to work.

This past week was a perfect example. The Friday prior, we had been notified that a few kids at daycare had gone home with low-grade fevers Thursday night. I silently cursed the people who sent these kids to school, although I knew that the kids had probably been fine before school that morning. But that didn’t stop me from worrying, as my daughter suffers from periodic fever syndrome. A low-grade fever lasting 24 hours in most kids can knock my daughter down for 5 days or more. Her temps often hit above 102 degrees and she is miserable.

Sure enough, the very next day my daughter woke up with a fever that quickly spiked to 102.7. And as per past fevers, it lasted a full 7 days. As if this was not bad enough, my 14-month-old woke up from her nap struggling to breathe. This necessitated a quick trip to the ER where she got steroids. This happened again about 36 hours later — back to the ER, where she got another dose of steroids and the lovely diagnosis of croup.

So, how do I make it work? Well, first, sometimes I don’t. Last week, I spent the entire week at home taking care of sick kids, doing my best to call into meetings and work as much as I could from my satellite home office. Thankfully, I only had one speaking event and a morning of clinic — and my husband was able to take that morning off, getting back to the high school just in time for practice. If, for whatever reason, we had not been able to make this arrangement, I would have had to cancel my clinic or try to find someone to cover it, which is not an easy task.

So, how do I make it work? Well, first, sometimes I don’t. Last week, I spent the entire week at home taking care of sick kids, doing my best to call into meetings and work as much as I could from my satellite home office. Thankfully, I only had one speaking event and a morning of clinic — and my husband was able to take that morning off, getting back to the high school just in time for practice. If, for whatever reason, we had not been able to make this arrangement, I would have had to cancel my clinic or try to find someone to cover it, which is not an easy task.

And if not for external support, we would not be able to make things work. I have a very supportive family living close by. When I know I have to travel, I clear dates with my mom, who steps in to pick up my kids from daycare, feed them, and get them ready for bed before my husband gets home. When my kids are sick and I have an important meeting I cannot miss, I ask for conference lines or arrange childcare with my father-in-law. There are also times when I run into roadblocks, and I have to put work aside and just focus on being a mama for the day. The hardest part is missing out on patient care. I think that any healthcare provider will tell you that putting patients first is natural. Having to adjust that mentality isn’t always easy.

The other answer to how I make it work is that I NEED to work. I have realized over the years that working is the key to my sanity. Don’t get me wrong — the love I have for my kids is indescribable. But I also love being a nurse, something I dreamed of since childhood. I love that I was one of the youngest bedside nurses in my new graduate cohort. I love that my Alaska Native heritage paid for a large portion of my college. I love that I was able to work full-time while attending graduate school. I love, despite the numerous obstacles faced throughout my years of education, that I succeeded. I love the worried well patients I see in clinic. And lastly, I love seeing the sick patients whom I have treated improve.

My career allows me an outlet, a way for my mind to work outside of being a mama. This allows me to be a better mama and truly appreciate both my career and my family. So when asked how I make both my career and motherhood work, I smile (after I finish laughing) and say, “family support and perseverance.”

I’d love to hear from other parents: How do you make it work?

November 9th, 2017

Time Off for Good Behavior: Vacation Cultures in the U.K. vs. U.S.

Megan Tetlow, PA-C

Megan Tetlow, PA-C, is from Fort Myers, Florida, now working in Sheffield, England, as part of the National Physician Associate Expansion Program. She practices in gynecologic oncology and is a guest blogger for In Practice.

When I met my doctor in the hall for rounds this morning, it occurred to me that I hadn’t seen her for a good month. We had each been alternately away — me camping in Iceland and my doc on her own holiday in sunny Spain. As she gave me a warm hello and asked with genuine enthusiasm about my trip and we chatted about our various adventures, I couldn’t help thinking that this conversation probably wouldn’t happen if I was working in the U.S. But why?

One reason is that all full-time U.K. employees have legally protected paid vacation time of 5.5 weeks. In contrast, the U.S. does not have any required vacation time, paid or unpaid. Among industrialized nations, this is uniquely American. According to recent U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics, 23% of Americans working in the private sector do not have any paid time off. And even if you are one of the lucky 77% who do have paid time off, the average you’ll get is just 2 weeks (after 1 year of service). It’s also worth pointing out that the paid vacation time mandated in the U.K. is additional to paid sick time. If you really want to make your British colleagues scratch their heads, try to explain the concept of paid time off (“PTO”) and how your sick time and vacation time can be one and the same.

Additionally, in the U.S., many Americans feel that they can’t take the vacation time they are given. A survey by Allianz Travel found that almost half of millennials (those aged 18-34) surveyed did not take the full amount of their allotted time off. And over half reported feeling either nervous, guilty, anxious, or shameful when they did request time off. These are very different attitudes from those I’ve observed in the U.K. Providers, staff, and administrators here all take their annual leave, and are highly encouraged to do so. It’s considered a right, not a privilege, and certainly has no bearing on how you’re perceived as a healthcare provider or employee.

Additionally, in the U.S., many Americans feel that they can’t take the vacation time they are given. A survey by Allianz Travel found that almost half of millennials (those aged 18-34) surveyed did not take the full amount of their allotted time off. And over half reported feeling either nervous, guilty, anxious, or shameful when they did request time off. These are very different attitudes from those I’ve observed in the U.K. Providers, staff, and administrators here all take their annual leave, and are highly encouraged to do so. It’s considered a right, not a privilege, and certainly has no bearing on how you’re perceived as a healthcare provider or employee.

There is also a culture here in the U.K. of supporting coworkers when they take vacation time. Upon returning from my first week-long holiday from my job in the NHS, I headed to my shared desk, gearing myself up to plow through the stack of results and letters that had surely accumulated in my absence. What I found instead was an empty cubbyhole, because my colleagues had already taken care of the work.

One last difference I have noticed is how patients react to their doctor being away. Perhaps because employees in the U.K. have leave (and take it), there’s not a question of “what do you mean Dr. xyz isn’t available?” My doctor will see a patient prior to surgery and will tell them: “I’m away the rest of the week, but the team will take good care of you” and never once have I seen a patient concerned about this. In fact, the only time I can recall a patient having a follow-up question was to ask my doctor if he or she was going somewhere nice.

One last difference I have noticed is how patients react to their doctor being away. Perhaps because employees in the U.K. have leave (and take it), there’s not a question of “what do you mean Dr. xyz isn’t available?” My doctor will see a patient prior to surgery and will tell them: “I’m away the rest of the week, but the team will take good care of you” and never once have I seen a patient concerned about this. In fact, the only time I can recall a patient having a follow-up question was to ask my doctor if he or she was going somewhere nice.

I urge all of us to take a page from the book of U.K. holiday norms. If you have vacation time, take it. Tell your patients you’re unavailable. Keep your laptop closed and your emailed signed out. Go do whatever brings you joy and encourage your colleagues to do the same. Offer to help manage your colleagues’ workload while they’re away. Finally, throw any feelings of guilt out the window. You simply can’t be the best provider you can be when you’re exhausted and burnt out. Self-care is not selfish. You need to take time to unwind and recharge. You owe that to yourself and to your patients too.

November 1st, 2017

Medical Trick-or-Treat

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

It’s one of my favorite times of year. The colors of the leaves are changing, there is a crisp feel to the air, and it’s Halloween time. The candy aisles are decimated, kids have donned their costumes and hit their preplanned routes or parties, and even some of the grown-ups have dressed up and managed to escape reality for a few minutes at a neighborhood fete. My mind on the “trick-or-treating” hubbub, I began to reflect on how my work can often feel like a professional version of this fun childhood tradition.

There are days when my whole shift feels like one big trick. Complex post–hospital discharge visits that require far longer slots than the one in which they’ve been booked, a walk-in complaint of chest pain, a request for 12 pages of paperwork that is due tomorrow, etc. This day is the equivalent of the neighbor in your childhood who used to drop a toothbrush into your pillowcase full of sweets.

Then there are treat days. A few “no-shows” sprinkled in between physicals for young, healthy folks with few complaints, writing and closing your notes as you go, reaching a patient with abnormal results without playing phone tag at all! This day is like finding the house on your street that is giving out full-size candy bars instead of the mini versions.

Some conditions and outcomes can feel like trick-or-treat situations as well. Sometimes the diagnosis seems so obvious, so clear, that you hesitate to even make a differential. For example, I saw a patient the other day in her early fifties who had all the hallmark signs of menopause and only ONE symptom of hypothyroidism. I almost didn’t check her TSH because it seemed such an open-and-shut case. But guess what — the trick was on me — her levels were through the roof. In this case, the hoofbeats didn’t point to the lead horse; there was a zebra in the crowd. (Now that I’m thinking of it, that would make a great group costume for a bunch of residents — a bunch of horses, one zebra. Anyway…). It’s so unexpected, like receiving a ketchup packet. (That really happened to me once as a kid.)

At other times, the outcome is surely a treat. A patient who is dear to me was diagnosed a few years ago with a kidney tumor. The prognosis was, as my childhood “Magic 8 Ball” might have predicted, “outlook not so good.” Based on the tumor characteristics on imaging, it had a less than 5% chance of non-malignancy. The renal team was lovely, and one fellow explained that the location of the tumor (close to the major vessels) would likely result in the removal of the entire kidney. And yet, when the surgery was complete, the attending called down saying that he had managed to remove it entirely without taking the kidney. And several days later, the path came back negative. Equivalent of a king-sized candy bar.

And then there are the mixed bags. Recently, a patient involved in a car accident underwent some imaging to rule out a musculoskeletal injury, and the CT showed an incidentaloma at the base of a lung. Follow-up showed that he indeed has lung cancer but, having been caught early, he has no metastases or lymph node involvement. The car accident was a trick, the nodule a trick, the cancer a trick — but finding it all before it was much worse and all by coincidence — kind of a treat.

In primary care practice, as in life, we never know what a day will bring. The surprising or unexpected turns — whether tricks or treats — keep us on our toes and perhaps make us better, more open-minded clinicians in the end.

October 31st, 2017

Call ‘Em Out: Harvey Weinstein, Bobo Dolls, and the Psychology of a Scolding

Harrison Reed, PA-C

Yet again this year, a familiar tale has dominated the news cycle: allegations of an individual who weaponized his power and influence to abuse colleagues and coworkers. While the high-powered world of Hollywood producers and movie stars might not resemble most of our workplaces, the underlying abusive mentality of Harvey Weinstein’s decades-long rampage is probably familiar territory for many.

Perhaps more disappointing than Weinstein’s behavior is the apparent impunity with which he operated. As is often the case, the powers governing the film industry only seemed driven to intervene after his deeds were exposed to the general public.

Most of us, however, will never work in the kind of high-profile setting that attracts a bona fide public scandal. When we witness abuse from those in power, the average person rarely expects the supportive firepower that comes from the glaring eye of the news media. In our anonymous workplace bubbles, we are left asking: what good can come from calling out abusive behavior and is it even worth the trouble?

Perhaps a 50-year-old psychology experiment can answer that question.

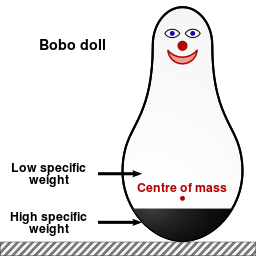

In the early 1960s, Albert Bandura and his colleagues set out to discover the effect of observed behavior on children. They conducted an experiment in which they divided young children into three “treatment” groups. For each group, individual children were placed in a room full of toys, including an inflatable clown figure called a bobo doll.

Children in a control group played in the room by themselves for 20 minutes. Children in a second group played while an adult entered the room and performed calm tasks. Children in the third group played in the toy room while an adult entered and verbally and physically attacked the bobo doll, even beating it with a hammer.

After this initial experience in the toy room, each child was then led to a second room full of toys, this one containing a bobo doll and a hammer. You can probably guess what happened next: children who had observed the aggressive behavior modeled by an adult were much more likely to emulate it, verbally and physically assaulting the bobo doll.

Of course, the idea that young children imitate the behavior of adults is not exactly groundbreaking science by today’s standards. But Bandura’s follow-up experiment two years later offers a particularly useful reminder.

In a variation on their original bobo doll experiment, Bandura and his research team again placed children in rooms of toys and again had an adult demonstrate aggressive behavior in front of them. This time, however, a second adult entered the room and either rewarded the behavior with praise and prizes or punished it with a scolding. When those children were placed in the next room with toys and the now thoroughly abused bobo doll, the children who had seen the aggression condemned did not mirror the behavior.

While most healthcare workers have achieved an emotional maturity beyond that of a five-year-old, the lessons of the bobo doll experiment still resonate in our workplaces.

Abuse and toxicity in our offices and hospitals is a cycle, with one generation of supervisors and employees passing the culture down to the next. Witnessing abusive behavior has a downstream effect, but the collective response to that behavior may matter even more. If workplace bullies are rewarded with complicity — or worse, achieve success and promotions — their behavior is far more likely to find copycats. If those same individuals are called out, if the behavior is publicly denounced, it is far less likely to be replicated by others.

Abuse and toxicity in our offices and hospitals is a cycle, with one generation of supervisors and employees passing the culture down to the next. Witnessing abusive behavior has a downstream effect, but the collective response to that behavior may matter even more. If workplace bullies are rewarded with complicity — or worse, achieve success and promotions — their behavior is far more likely to find copycats. If those same individuals are called out, if the behavior is publicly denounced, it is far less likely to be replicated by others.

Of course, asking someone to be the first to speak out, especially when an abuser holds power or influence, is no small request. There is a perceived — and often very real — danger of retaliation for such an act. But establishing a unified front ahead of time can make a big difference.

Each workplace should have an official, public policy regarding abusive behavior and the expected response to it. As flimsy as a sheet of paper may be, that can provide some initial cover for the brave individuals who do the tough work of calling out toxic behavior. The strongest results, however, will come when an organization’s leaders apply the lesson of the bobo doll experiment and denounce inappropriate behavior for all to see.

October 17th, 2017

Emergency Medicine: A Life of Interruption

Alexandra Godfrey, BSc PT, MS PA-C

Emergency medicine is a life of interruption. Physicians, nurses, PAs, radiology techs, registration clerks: we are all constantly interrupted or interrupting. Unfortunately, interruptions and distractions and the consequent attention shift may lead to error. Sometimes, we fail to return to the original task, make an error in that task, or waste time on less urgent needs, neglecting critical ones.

Learning when to focus and when to ignore a distraction is perhaps one of the most vital skills needed in emergency medicine. Working in the ER can lead to a culture of immediacy; everything is now, yesterday, too late already. But seriously — is it? Just because we want something STAT, does it need to be STAT?

Recently, as part of a course in narrative medicine, I have been studying attention, awareness and mindfulness. I realized as I studied this material that not only is interruption frequent in emergency medicine, it is also widely accepted. Yes, if the patient is moribund, exsanguinating, showing tombstones on his EKG or otherwise in extremis, then interruption is essential and valid. But what about all the other times — the telephone calls, the verbal interruptions, the pages, the side conversations?

Here are some interruptions I noticed during a recent ER shift:

Here are some interruptions I noticed during a recent ER shift:

- A clerk is on the phone. A doctor asks her to page a specialist.

- A PA is putting orders in on a patient. The triage nurse stops by and asks her to review an EKG.

- A nurse is drawing up meds to give to a patient. A PA interrupts her, asking if she will get discharge vitals on another patient.

- The physician is taking a history. The registration clerk enters the room and asks the patient for insurance information.

- The NP is reviewing imaging. The radiology tech stops by and advises him to order a creatinine on another patient.

- A physician is doing a critical procedure on a patient. A nurse walks in and asks him if she can give Zofran to another patient.

- Two physicians are doing sign-out. The social worker interrupts to discuss a psychiatric admission.

Health care systems researchers have documented interruptions in health care environments, including the relatively high interruption rate in emergency departments compared with primary care. Other evidence supports the observation that, once interrupted, ER providers frequently fail to return to the task. Moreover, attention shifts can lead to procedural errors and incomplete patient orders and evaluations.

Given these risks, could we establish protocols or an etiquette that would reduce the number of distractions and interruptions?

I think we can.

Here are some ways we might start.

First, we could each consider the import of our interruptions – i.e., ask ourselves:

- Do I need to ask this now?

- Does this need immediate attention?

Another idea is for departments to identify critical tasks where interruption is most dangerous, such as:

Another idea is for departments to identify critical tasks where interruption is most dangerous, such as:

- Provider sign-out

- Nurse medication preparation and administration

- Patient evaluation by medical staff

- Clinician review of labs and imaging

- Putting in orders

- Patient procedures

Such tasks could be designated as protected from non-emergent interruption. ERs might also consider developing protected work stations (areas), limiting phone calls, programming EMR cues, and setting monitor alarms to safe and appropriate levels.

At the individual level, developing awareness is also a tool to mitigate distraction. Awareness requires us to be reflective and notice what does and does not interest us — and to recognize when an attention shift occurs. I am aware that being interrupted or distracted while I am putting in orders can result in a dangerous attention shift. Consequently, I consider this protected time. Unless a critical need arises, I finish these tasks first. Awareness has helped me focus my attention and avoid errors.

Being able to bring back a wandering attention — and knowing it has wandered — is one way each of us can lessen the effects of a chaotic and noisy environment. Other tools that might help are:

- List writing and post it notes

- Limiting off-topic conversations

- Limiting the number of visitors

- Posting “do not disturb” signs during critical procedures

- Limiting cell phone use by patients and their visitors

Interruption reduction is the responsibility of every member of the medical team. As both interrupters and the interrupted, I suggest we start by asking ourselves two simple questions at these moments:

Is this an appropriate time?

Should I delay this interruption?

October 5th, 2017

An Old Procedure, A New Beginning

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN practices pediatric cardiovascular care across the Pacific Northwest.

“My heart hurts,” said Brooklyn, then three years old, as she grabbed her chest and sat down. Quickly checking the girl over, Brooklyn’s parents felt her heart indeed pounding in her chest, and took her to the emergency department. There, they were shocked to hear that their daughter was in cardiac arrest. Shortly afterward, Brooklyn was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension. The following few years brought a multitude of procedures, medications, and doctor appointments.

After two years, the disease started to take its toll, and Brooklyn had increasing cyanosis. On the recommendation of their doctors, the family moved to Seattle to be at sea level. Initially, Brooklyn’s symptoms improved, but over the years, her health steadily declined. At eight years old, she was maxed out on medications, no longer growing, and unable to walk without shortness of breath — and her family was looking at transplantation as the only option. Unfortunately, due to her rapidly deteriorating disease combined with constant insurance obstacles, transplantation seemed out of reach.

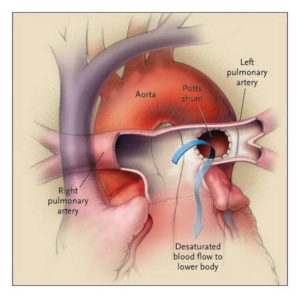

Looking as if they were out of options, their pulmonary hypertension specialist Dr. Delphine Yung introduced another option she had read about. It involved repurposing the once failed Potts shunt to redirect excess blood in the pulmonary artery to the aorta. (Created in 1940, the Potts shunt was meant to be used for the reverse purpose, to augment pulmonary blood flow. However, it quickly went out of favor because in many cases it had worked too well, causing pulmonary hypertension.)

Looking as if they were out of options, their pulmonary hypertension specialist Dr. Delphine Yung introduced another option she had read about. It involved repurposing the once failed Potts shunt to redirect excess blood in the pulmonary artery to the aorta. (Created in 1940, the Potts shunt was meant to be used for the reverse purpose, to augment pulmonary blood flow. However, it quickly went out of favor because in many cases it had worked too well, causing pulmonary hypertension.)

Presenting her idea in a patient care conference with the cardiac surgical team, Dr. Yung explained that she had heard of the Potts shunt being used successfully in a few cases of pulmonary hypertension abroad and then later in the U.S., and she felt it held potential for Brooklyn. Our chief of cardiac surgery, Dr. Jonathan Chen, stated his concerns about the complexity of the surgery for patients with pulmonary hypertension. However, after researching the revised use of this shunt further, he was persuaded that it was worth going out on a limb to try to improve Brooklyn’s life.

Both Dr. Yung and Dr. Chen approached Brooklyn’s family with the idea of the repurposed shunt placement. Her parents were understandably nervous about the idea, as their daughter would be one of the few patients in the world to undergo this surgery. But knowing they were out of options, the family agreed to move forward with the surgery.

The operation by Dr. Chen went smoothly, and Brooklyn’s vital signs indicated nearly instant relief for her heart.

Within a few weeks of surgery, Brooklyn’s medications were decreased and then stopped. She was weaned off oxygen, and a central line that had been in place for years was removed. She was finally able to go swimming and start living life to her full potential. Her parents were beyond grateful for the success of the procedure. To paraphrase Dr. Chen, it took an incredible amount of courage for these parents to try the shunt and trust the health care team with this decision. [He also reflected how, as a wedding is the mark of a new life, so was this procedure for Brooklyn and her family. And as with a well-known wedding tradition, her case even involved something old (the abandoned procedure), something new (its new use), something borrowed (the shunt and procedure techniques), and something blue (the cyanosis, now improved postprocedure).]

Brooklyn is now nearly three years post-surgery and doing remarkably well. Dr. Yung and Dr. Chen have one other patient who has since undergone the procedure with a similar outcome.

I am often in awe of the power of medical science to help us achieve advances in health care, and this particular story, and the remarkable level of success for the patient, are the best example of this I have witnessed.

September 29th, 2017

I’ll Take “Nursing Ethics” for $200, Alex

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

First I noticed it all over my social media feed — the story of Alex Wubbels, a burn unit nurse at a university hospital in Utah who was arrested and manhandled by police for not allowing them to take a sample of blood from an unconscious patient without a warrant. Then came a slew of texts, emails and calls from people wanting to discuss the incident, asking me what I thought. Most recently, it came up while laying on the beach with family members, who wanted my reaction to the event.

My reaction is this: I could have been Alex Wubbels. I would have done the same thing she did. And the realization of that fact — after seeing how she was treated for following hospital policy and for protecting her patient — is kind of terrifying but also empowering. But I think most nurses would have done the same and here’s why.

Alex Wubbels knew the hospital policy and she followed it. By nature, I am detail-oriented and I adhere to guidelines. By education and training, my natural tendencies have been “encouraged.” I was taught how to make a perfect bed; I know how to calculate a drip rate by hand using stoichiometry and not a calculator; I have counted another human’s urinary output over a 12-hour period to the milliliter. If a patient is on precautions, you damn well better believe I have “gowned and gloved” to a tee for that level of need. When a parent calls my office about an adult child, the first thing I ask is if we have a signed release on file to share information with the caller — because otherwise, we are not legally allowed to disclose health information of the patient; it is protected under HIPAA.

Alex Wubbels knew the hospital policy and she followed it. By nature, I am detail-oriented and I adhere to guidelines. By education and training, my natural tendencies have been “encouraged.” I was taught how to make a perfect bed; I know how to calculate a drip rate by hand using stoichiometry and not a calculator; I have counted another human’s urinary output over a 12-hour period to the milliliter. If a patient is on precautions, you damn well better believe I have “gowned and gloved” to a tee for that level of need. When a parent calls my office about an adult child, the first thing I ask is if we have a signed release on file to share information with the caller — because otherwise, we are not legally allowed to disclose health information of the patient; it is protected under HIPAA.

“Hospital policy” has gotten a lot of flak in the dust-up that has followed this incident — but it exists for a reason, and it is my job and every hospital professional’s job to know it and to follow it, just like Alex did. While it may be impossible to know every policy, providers are trained on where policies are kept, how to read and interpret them, and also how to access supervisors as backup. According to the video footage of the incident, Alex did all of that, and most nurses I know would have done the same. We are cut from this same cloth and trained in the same way.

While most people are familiar with the oath that physicians take to “do no harm” (who knew Hippocrates would still be quoted 2000+ years after his death?), reflecting on this incident made me wonder: Does anyone know where nurses get their call to provide care and avoid harm? The answer is that some graduating nurses still recite the Nightingale pledge made famous by another nurse in the late 19th century. But our working ethics go beyond this pledge. Nursing education is infused with the principles of caring, integrity, and excellence from start to finish. We are taught that our role centers around advocating for patients and families. We are called to integrate this into our daily practice. While in school, we buy and read copies of the 72-page ANA “Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements,” we study the concepts of Jean Watson’s theory of human caring, and we complete courses titled “Ethical Issues in Advanced Practice Nursing.” It is deeply ingrained within the collective nursing psyche to do what Alex Wubbels did — to put the patient first and advocate for patients, especially when they cannot advocate for themselves.

While most people are familiar with the oath that physicians take to “do no harm” (who knew Hippocrates would still be quoted 2000+ years after his death?), reflecting on this incident made me wonder: Does anyone know where nurses get their call to provide care and avoid harm? The answer is that some graduating nurses still recite the Nightingale pledge made famous by another nurse in the late 19th century. But our working ethics go beyond this pledge. Nursing education is infused with the principles of caring, integrity, and excellence from start to finish. We are taught that our role centers around advocating for patients and families. We are called to integrate this into our daily practice. While in school, we buy and read copies of the 72-page ANA “Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements,” we study the concepts of Jean Watson’s theory of human caring, and we complete courses titled “Ethical Issues in Advanced Practice Nursing.” It is deeply ingrained within the collective nursing psyche to do what Alex Wubbels did — to put the patient first and advocate for patients, especially when they cannot advocate for themselves.

An annual national Gallup poll of Americans has ranked nursing the highest among 21 major professions in terms of honesty and ethics — for the 15th year in a row. Our patients place their trust in us to care for them and ensure no harm comes to them. So, thank you, Alex Wubbels, for this example of what it is to be a nurse, for reminding us of our calling.

September 21st, 2017

The Opioid Epidemic: One Year Later

Harrison Reed, PA-C

A year ago I wrote a blog for In Practice and an editorial in the Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants (JAAPA) that discussed the factors contributing to the opioid epidemic in America. If the passionate reaction to those articles is any indication, the topic stirred both intellect and emotion.

Since then, the issue of opioid abuse/overdose has not disappeared. Let’s take a look at some of the recent developments.

New Data Released

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other government agencies released new data last week that shed further light on the opioid crisis. These latest data show the number of drug overdose deaths from February 2016 through February 2017. This dataset is important as it is the first to include the period of time following the CDC’s updated 2016 opioid prescribing recommendations and the media frenzy that followed.

Here are the trends you should know. Deaths from the three most prevalent opioid types—natural/semi-synthetic (like oxycodone/hydrocodone), synthetic (like fentanyl), and heroin—all increased over the past year despite reported drops in prescribing rates. But the largest increase in deaths was from synthetics like fentanyl (more on that later). The geographic distribution of drug overdose deaths is also uneven, with some parts of the country reporting a decline (like an 8% drop in Nebraska) while others have seen an explosion in cases (like a 63% increase in Maryland).

The Rise of Fentanyl

Another storyline has emerged from both data trends and media reports: the rise of illicit fentanyl. While the potent synthetic opioid has been a useful tool in certain medical settings for years, its illicit manufacture and abuse is one of the most significant developments in the opioid saga.

Stories of fentanyl’s immediate impact have filtered from some of the country’s hardest-hit areas. The drug is much more potent than typical heroin and is often combined with or laced into other drugs, sometimes unbeknownst to the user. That unpredictability has resulted in body counts that, for some communities, have been treated as mass-casualty events.

A wider view of the raw numbers is startling. The one-year CDC data mentioned above show that 14,465 people overdosed on natural and semi-synthetic opioids (like oxycodone and hydrocodone) while 15,549 people overdosed on heroin. But in the same period of time, 21,163 people died from synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Easily manufactured and highly lethal, synthetic opioids have become a frightening game-changer in the opioid epidemic.

Alternative Narratives

The arrival of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids as a major player in the overdose epidemic may have also opened the door for a troubling narrative. Some in the media and medical community—like the author of this editorial published in Emergency Medicine News—point to the rise of illicit fentanyl deaths as proof that the medical community is not responsible for the epidemic.

This flawed viewpoint implies a lack of obligation on the part of clinicians to find solutions to the nation’s opioid dependence. It also ignores the fact that the vast majority of illicit opioid users began with a prescription drug.

You can read more analysis of this false fentanyl narrative at my website The Contralateral.

President Trump Makes a Statement

The opioid epidemic received some high level attention last month when President Trump issued a verbal statement on the issue.

“The opioid crisis is an emergency, and I’m saying officially right now: it is an emergency,” he said on August 10th from the steps of his New Jersey golf club.

While the comment from the nation’s top official brings an added spotlight, it may lack the formality needed to spur additional action. Saying something is an emergency and signing a formal declaration of emergency are two different things. The latter would have several beneficial effects: it would make FEMA money available to states in need of assistance, allow the redeployment of Health and Human Services (HHS) personnel, and remove Medicare restrictions that act as barriers to substance abuse treatment.

A formal declaration may not happen, though, if HHS Secretary Tom Price’s comments are any indication.

“We believe that, at this point, that the resources that we need, or the focus that we need to bring to bear to the opioid crisis can be addressed without the declaration of an emergency,” he said shortly before the President’s statement.

Despite not having a formal presidential declaration, the CDC recently awarded an additional $28.6 million to 44 states and D.C. to help combat the opioid epidemic. The funding was part of a congressional appropriations bill signed by President Trump earlier this year and will expand several HHS programs.

The money will help states bolster prescription drug monitoring programs, increase opioid risk awareness outreach, and improve surveillance and data-gathering programs.

There are many more opioid-related storylines that we don’t have time to cover in this blog. As new data emerge, we will need to continually reassess the impact of the epidemic and the efficacy of our interventions. If you have an important update to add, please post it in the comment section.

September 15th, 2017

Curbside Consultations: Checks and Balances

Alexandra Godfrey, BSc PT, MS PA-C

A 34-year-old male presents to the emergency department with right arm weakness. He woke up 2 days ago unable to move his arm. The patient reports having hypertension but has no history of diabetes, stroke, cardiac disease or tobacco use. He drinks alcohol daily. The patient complains of numbness and tingling in his arm. He lacks wrist extension and has diminished grip power. His function in his biceps and triceps is normal. He has no other deficits or symptoms. You suspect the patient has a radial nerve palsy but feel a little uneasy because he appears to also have some involvement of the ulna and median nerves.

The neurologist has just finished seeing another patient in the ED. You wander over to him as he settles down at the computer to chart. After some small talk, you mention you have a patient with what appears to be a radial nerve palsy but you are questioning why this patient has decreased grasp and pinch strength. You chat for a while about different nerve palsies and ways to isolate peripheral nerves; then you answer his questions about findings suggestive of more serious lesions. When you re-examine your patient based on your conversation, you feel comfortable that the patient has a radial injury. Later, you sit down to chart, and you wonder whether you should document your discussion with the neurologist.

Informal, or “curbside,” consultations are a common and expected part of our medical practice. It’s checks and balances. We talk with each other when we encounter a presentation or condition that is outside of our usual area of expertise or just doesn’t fit the text. This can improve patient care and show thoughtfulness on the part of clinicians. Additionally, talking with colleagues — unlike reading textbooks and consulting web apps — allows for bidirectional learning.

However, such discussions are not risk free. For example, without knowing the specifics of a case or formally examining the patient, a consultant might offer well-intended advice that is inaccurate, incomplete or inappropriate. This can get us into deep water. Additionally, if the treating clinician shares insufficient information with the consultant, she might adversely affect patient care or have misplaced confidence in subsequent management of the patient. Sometimes there’s a disconnect between the consultant and the treating provider about what exactly is being asked. And humans being humans, recall later is likely to be different.

Risk Management

Generally speaking, risk is related to the degree of control the clinician has over patient care. The treating clinician — the individual who is directing care — carries the weight of responsibility for the patient and the medico-legal risk. Just because you discussed the case with the consultant doesn’t mean you are protected. If the consultant puts in orders or examines the patient, professional liability shifts.

Of course, medico-legal risk fluctuates according to setting, access to specialist services, and decisions made as a result of informal consultation discussions. Sometimes a face-to-face consultation is not possible and waiting for one would result in a delay in care. I work 72 miles from a tertiary center and frequently depend on telephone consultations. Some specialists are just not available at my primary site. In these circumstances, an informal consult may be better than no consult. Sometimes, I transfer the patient. This is usually a shared decision between myself, my attending, and the consultant. Such discussions help us identify the correct specialist, prioritize follow-up, and decide on need for transfer. (Here are a few citations I like on decision-making regarding informal consultation and care coordination.)

What topics are suitable for informal consultations?

What topics are suitable for informal consultations?

Academic questions, discussion of new research, requesting follow-up, and utility of tests are all topics that might be suitable for an informal consult. We learn through discussion and it is important that such learning isn’t lost. It’s good to bounce ideas off each other. In the hypothetical case presented, the treating clinician could ask simple questions like:

What is the best way to evaluate for a radial nerve palsy?

Do you think steroids have efficacy in the treatment of nerve palsies?

As a matter of courtesy and professionalism, I avoid documenting the consultant’s name in the medical chart without their permission. I have met consultants upset to find their names in charts of patients whom they have never formally assessed. Asking if you can document the consultant’s name clues specialists in to the import of any advice given and prevents any surprises. I believe this is a mark of collegial respect, engendering the open and honest discussions much needed in medicine.

When is a formal consultation indicated?

As a treating clinician, I consider seeking a formal consult if questions are complex or the consultant needs to examine the patient or review records to give good advice. Additionally, if the patient knows about the consult or if the treatment pathway is dependent on the consultant’s expertise, then a formal consult is warranted. If the consultant orders tests or treatments, this should precipitate a formal consult.

This leaves me with two questions:

How can we improve the safety and utility of curbside consults?

How do you manage curbside consults?