October 31st, 2017

Call ‘Em Out: Harvey Weinstein, Bobo Dolls, and the Psychology of a Scolding

Harrison Reed, PA-C

Yet again this year, a familiar tale has dominated the news cycle: allegations of an individual who weaponized his power and influence to abuse colleagues and coworkers. While the high-powered world of Hollywood producers and movie stars might not resemble most of our workplaces, the underlying abusive mentality of Harvey Weinstein’s decades-long rampage is probably familiar territory for many.

Perhaps more disappointing than Weinstein’s behavior is the apparent impunity with which he operated. As is often the case, the powers governing the film industry only seemed driven to intervene after his deeds were exposed to the general public.

Most of us, however, will never work in the kind of high-profile setting that attracts a bona fide public scandal. When we witness abuse from those in power, the average person rarely expects the supportive firepower that comes from the glaring eye of the news media. In our anonymous workplace bubbles, we are left asking: what good can come from calling out abusive behavior and is it even worth the trouble?

Perhaps a 50-year-old psychology experiment can answer that question.

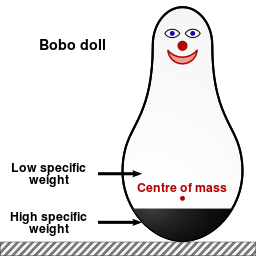

In the early 1960s, Albert Bandura and his colleagues set out to discover the effect of observed behavior on children. They conducted an experiment in which they divided young children into three “treatment” groups. For each group, individual children were placed in a room full of toys, including an inflatable clown figure called a bobo doll.

Children in a control group played in the room by themselves for 20 minutes. Children in a second group played while an adult entered the room and performed calm tasks. Children in the third group played in the toy room while an adult entered and verbally and physically attacked the bobo doll, even beating it with a hammer.

After this initial experience in the toy room, each child was then led to a second room full of toys, this one containing a bobo doll and a hammer. You can probably guess what happened next: children who had observed the aggressive behavior modeled by an adult were much more likely to emulate it, verbally and physically assaulting the bobo doll.

Of course, the idea that young children imitate the behavior of adults is not exactly groundbreaking science by today’s standards. But Bandura’s follow-up experiment two years later offers a particularly useful reminder.

In a variation on their original bobo doll experiment, Bandura and his research team again placed children in rooms of toys and again had an adult demonstrate aggressive behavior in front of them. This time, however, a second adult entered the room and either rewarded the behavior with praise and prizes or punished it with a scolding. When those children were placed in the next room with toys and the now thoroughly abused bobo doll, the children who had seen the aggression condemned did not mirror the behavior.

While most healthcare workers have achieved an emotional maturity beyond that of a five-year-old, the lessons of the bobo doll experiment still resonate in our workplaces.

Abuse and toxicity in our offices and hospitals is a cycle, with one generation of supervisors and employees passing the culture down to the next. Witnessing abusive behavior has a downstream effect, but the collective response to that behavior may matter even more. If workplace bullies are rewarded with complicity — or worse, achieve success and promotions — their behavior is far more likely to find copycats. If those same individuals are called out, if the behavior is publicly denounced, it is far less likely to be replicated by others.

Abuse and toxicity in our offices and hospitals is a cycle, with one generation of supervisors and employees passing the culture down to the next. Witnessing abusive behavior has a downstream effect, but the collective response to that behavior may matter even more. If workplace bullies are rewarded with complicity — or worse, achieve success and promotions — their behavior is far more likely to find copycats. If those same individuals are called out, if the behavior is publicly denounced, it is far less likely to be replicated by others.

Of course, asking someone to be the first to speak out, especially when an abuser holds power or influence, is no small request. There is a perceived — and often very real — danger of retaliation for such an act. But establishing a unified front ahead of time can make a big difference.

Each workplace should have an official, public policy regarding abusive behavior and the expected response to it. As flimsy as a sheet of paper may be, that can provide some initial cover for the brave individuals who do the tough work of calling out toxic behavior. The strongest results, however, will come when an organization’s leaders apply the lesson of the bobo doll experiment and denounce inappropriate behavior for all to see.

I guess the piece of paper, or ombudsman, or HR staff, or “whistle blower” are all responses to the absence of corporate ethical responsibility – unless shamed in the Court of public opinion, usually after the damage is done, decades later usually. Does this explain how a corporation can sue a government for loss of income opportunity because that government wont sell its rain forest, oil or water?

Back to clinical reality – fill the vacuum – be the missing conscience, proudly, with confidence. But watch your back and get support.