April 4th, 2017

Of Little Hearts and Little Teeth

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN practices pediatric cardiovascular care across the Pacific Northwest.

Recently, I had to cancel a child’s heart surgery because she had multiple cavities. I recall spending close to an hour explaining the surgical process and obtaining a complete history and physical only to then discover obvious caries on multiple teeth during an oral exam.

Turning to the parents, I asked when their daughter had last seen a dentist, not shocked to hear, “Never.” I remember the look of defeat on their faces when I told them she would have to see a dentist before undergoing surgery. Traumatized by this news, the parents told me they hadn’t seen a dentist because their child had heart disease and it wasn’t a priority. Imagine their surprise when this seemingly small detail caused their daughter’s needed surgery to be canceled.

Although my world of cardiology and the world of dentistry don’t collide every day, when they do, it usually has a big impact on me and my patients. Despite the infrequency of these moments, they remind me of the importance of dental health care beyond good hygiene.

Although my world of cardiology and the world of dentistry don’t collide every day, when they do, it usually has a big impact on me and my patients. Despite the infrequency of these moments, they remind me of the importance of dental health care beyond good hygiene.

Children are recommended to have their first dental visit by age 1. The earlier that dental health is established as routine primary care, the earlier it becomes habit. Though professional care is necessary for maintaining oral health, sadly, a recent statistic I saw indicates that 25 percent of poor children have not seen a dentist before kindergarten.

In my experience, most of my patients lack the understanding of the importance of a healthy mouth and its relationship to overall health. As a provider, I see this as an obstacle that shouldn’t exist.

So, some things I am doing include educating my patients about the importance of brushing and flossing, and avoiding soda and other foods with excess sugar. Also stressing the importance of seeing a dentist every six months, or at least when possible. In addition, I have begun to educate parents of small children to be more involved in the act of teeth brushing, as the average toddler does not have the dexterity to properly brush his or her teeth.

In our current political climate, I do not foresee access to dental care improving. I am not a dentist and certainly do not claim to be an expert in dental hygiene. However, as a provider, the duty to give patients appropriate anticipatory guidance regarding a healthy mouth is something I take seriously.

In our current political climate, I do not foresee access to dental care improving. I am not a dentist and certainly do not claim to be an expert in dental hygiene. However, as a provider, the duty to give patients appropriate anticipatory guidance regarding a healthy mouth is something I take seriously.

With regard to my preoperative cardiac surgery patients, our coordinators advise parents that their child needs to see a dentist prior to surgery. And since the above incident, I make sure that dental care is one of the first history and physical questions I ask when entering a patient’s room. Talking about oral health and the need for a dentist isn’t always easy; however, it is devastating to have to tell a parent that their child cannot undergo open heart surgery until a cavity is treated. And preventing that seems well worth it.

References on Children’s Oral Health

March 29th, 2017

Deep Brain Stimulation Targeting in Neurosurgery, Part II of III

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

This is Part II of a three-part series on deep brain stimulation (DBS) targeting designed for providers who lack an intimate level of knowledge and/or experience with this subject matter. In Part I, the ventralis intermedius (VIM) target as well as an overview of DBS, equipment, and programming were discussed.

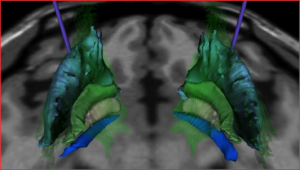

Globus Pallidus Internus (GPi)

Where is it located?

The GPi is located in the basal ganglia inferior and medial to both the putamen and globus pallidus externa (GPe) and just superior to the optic tract.

Indication for Targeting:

- Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

- Stimulation of the GPi treats the cardinal motor symptoms of PD, but less effectively compared with STN stimulation.

- GPi should be considered if a patient is having significant difficulty with levodopa-induced dyskinesia but an increased dose for cognitive benefits is desired. Of note, GPi stimulation typically does not lead to a reduction in PD medication [1].

- GPi treats dystonia secondary to PD well.

- Primary dystonia

- GPi is the primary target for hereditary dystonia and generally has excellent outcomes with good patient selection.

- VIM and STN are not generally used for dystonia.

Cautions:

- GPi is a large target requiring higher voltage settings to achieve symptom improvement. This requires more frequent battery changes or the consideration of a rechargeable battery. With a young-onset PD patient, this is an important consideration over the lifetime of the patient for both cost and wear and tear on the surgical site.

- Postural instability is not well treated with GPi stimulation.

Adverse side effects of stimulation based on location of electrode in relation to optimal placement [2]:

Too lateral – With simulation of the GPe, expect to see little to no effect on symptoms.

Too medial – With stimulation of the internal capsule (located medial and posterior to the GPi), unwanted muscle contractions can occur.

Too posterior – Same effects as placement too medially

Too anterior – Little to no effect on symptoms

Too superior – Same effects as placement too laterally

Too deep – Since the optic tract lies just deep to the GPi, stimulating it results in the patient seeing phosphenes (rings or spots of light perceived by the patient without actual light entering the eye).

In Part III of this series, I will address the final most commonly used DBS target, the sub thalamic nucleus (STN).

References

- Groiss SJ, Wojtecki L, Südmeyer M, Schnitzler A. Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease. Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders. 2009;2(6):20-28. doi:10.1177/1756285609339382.

- DBS Anatomy & Side Effects. A Presentation by Kirk Finnis, PhD. Medtronic.

March 23rd, 2017

When Medicine Is Hard

Megan Tetlow, PA-C

Megan Tetlow, PA-C, is from Fort Myers, Florida, now working in Sheffield, England, as part of the National Physician Associate Expansion Program. She practices in gynecologic oncology and is a guest blogger for In Practice.

My posts are usually lighthearted and (hopefully) informative observations on the differences between my experiences in medicine here in the U.K. versus the U.S. But today I am writing about something that’s both personal and cross-cultural — something that has at times been a struggle for me and likely has been a struggle for health care providers in every corner of medicine, whether we talk about it or not. I’d like to write about when medicine is hard.

By hard, I don’t mean the administrative hurdles and organizational dictums that occasionally make medicine a bit annoying. Nor do I mean the diagnostic puzzles that make health care interesting and challenging. I mean when medicine is emotionally noxious. For me, in my work in oncology, a hard moment is when my clinical skills have led to a definitive diagnosis but that academic success is eclipsed by what the diagnosis means for the patient. I know that tomorrow in clinic I will sit face to face with a person, not a histology report, and use the words “cancer” and “staging” and “aggressive.” That I’ll deliver news that, no matter how kindly spoken, will be a destructive, emotional wrecking ball.

Then, because I’m a professional, I’ll walk out of that room and go about the rest of my day. I will still have a full clinic of patients to see, despite the pit in my stomach, and despite the whole world changing for my last patient. No rest for the weary in medicine.

Then, because I’m a professional, I’ll walk out of that room and go about the rest of my day. I will still have a full clinic of patients to see, despite the pit in my stomach, and despite the whole world changing for my last patient. No rest for the weary in medicine.

It’s both different and the same for practitioners in any specialty. For an ER provider, it may be the third code blue in as many hours. For a trauma provider, perhaps a fatal motor vehicle collision at the hands of an impaired driver. For an ICU provider, it might be discussing terminal extubation. Or for a family practice provider, counseling a patient that her forgetfulness is a symptom of something serious.

So what do you do? The best you can do, as always. When you’re with your patient, speak with compassion and empathy, but also honesty. Talk to your patients like you would want someone to talk to you, or to your parent, sibling, or friend. Afterwards, decompress. Take a deep breath. Take a short walk. After the craziness of the day, talk to your spouse, your best friend, your colleagues. Seek out support offered by your hospital or organization. Most importantly, don’t lie to yourself about your emotional invincibility. Do you know that healthcare provider who is always extremely compassionate but yet never lets anything get to him or her, ever? Me neither. It’s a myth.

There is no weakness in seeking support from your colleagues and loved ones. And you’re not flawed if occasionally your work follows you home. When I was lamenting a particularly tough day delivering particularly bad news, my husband said “I know it’s hard, but I’m glad it was you.” On seeing my puzzled look, he expounded: “If I had to get news like that, I would want it from someone who cares, even if it’s tough.” We’re all here to support our patients, and just as importantly, each other. In health care, we work as a team. Let’s do our best to take care of our teammates. In the world of medicine and beyond, we do our best, and we get by with a little help from our friends.

In the comment section below, please share any tough experiences you’ve had as a healthcare provider, or, if you are a student, perhaps any fears you have about handling situations like this in the future. Let’s start a dialogue so that we can better support our colleagues and ourselves.

March 8th, 2017

Planning for End-of-Life Care: Patients and Providers Working Together

Elizabeth Donahue, RN, MSN, NP-C

I was sitting alone in a parking lot last Tuesday, waiting to meet one of my undergraduate students and her nursing preceptor for a hospice home visit. Little did I know, sitting there in my car, that I would not make it to that visit; instead I was redirected by a phone call to the home of a different hospice patient. My grandmother had passed just a few minutes earlier, under the care and watch of another hospice team and several family members.

Since that Tuesday, I’ve been thinking a lot about the experience of my Nina – her life, of course, but even more so, her death. She lived on her own terms, and I believe that due to a very dedicated care team and the involvement of family members, she was able to die on her own terms as well.

In my role as a clinical instructor, I have learned much from watching my nursing students shadow hospice nurses during the past 3 years. Some lessons: First, you never know what to expect when you enter a patient’s home. Second, time and a listening ear are sometimes the most impactful nursing interventions. Third, serious illness brings a significant range of emotions and reactions from both patients and families. Fourth, conversations about end of life are shockingly infrequent, even in elderly and ill patients.

Getting into that last point, roughly 70% of Americans do not have a health care proxy, mostly due to a lack of awareness of tools and options. This dearth of planning might be easily overcome by increased provider-led conversations. The literature reveals the following: lack of awareness is the most significant barrier; providers can complete forms during office visits; and most people would decline significant lifesaving intervention, thereby saving significant medical costs and emotional trauma for themselves and their families.

As a result, I’ve recently begun to think about having these discussions with some patients in my ambulatory clinic setting, especially because the topic keeps coming up. For instance, over the summer, our office operationalized a workflow for Medicare patients’ annual visits that includes asking a patient if she has a health care proxy, providing her with a form, and offering to witness the form and put it in her electronic medical record. A health care proxy is a basic tool that allows patients to select a delegate empowered to make medical decisions on their behalf if they were to become incapacitated. It is also the beginning of a conversation for patients and providers and, moreover, opens the door to important conversations between patients and those selected as proxies.

In December, a friend forwarded me an article from the Harvard Business Review about conversations between patients and providers about death. I found myself nodding in agreement with this excerpt: “We launched the program in primary care settings, where we guessed that doctors’ long-term and trusting relationships with their patients would ease these conversations.” I thought, yes! I had already found this to be the case when discussing health care proxies with patients. I was sure I could talk about MOLST (Medical Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment) forms, values, and wishes more comfortably than a registrar at the emergency department or a nurse in the ICU could. I was sure I could gently suggest that a spouse, partner, or child who was already looped into medical decisions could share in this process. I wanted to make an effort but was left with questions about how to do it: With which patients? Where should I start? How could I work this into my already busy patient visits?

Lo and behold, a few weeks ago, one of the authors of the HBR article walked into my office conference room to talk about his program with my primary care colleagues. Dr. Lakin made recommendations about how to approach the end-of-life care planning conversation with patients, how to integrate documentation into our records, and even how to bill for such efforts. He shared that, in his experience, relatively few patients (sometimes only a handful out of a panel of hundreds) are approached by their primary care providers for this discussion. It struck me in that moment that we have an opportunity to do so much better, for the sake of our patients and their families.

And the consequences are real. A hospice nurse recently shared with me the heartbreaking story of a patient in her care who had an unclear intent for end-of-life care. Her family had not communicated well and were in disagreement. The patient began to decline rapidly and in the absence of advanced directives or a clear proxy, an ambulance was called. Despite having talked with her nurse about her wish to end her life at home without heroic measures or intervention, the woman passed away in the hallway of a hospital waiting to be triaged.

As for my grandmother, I am immeasurably grateful to her primary care team. She had a nurse practitioner of whom she spoke highly, who ensured she had the care she needed and worked with her hospice team directly (and who called the day she passed, which meant so much to her family caregivers). I was not with my grandmother when she passed away, but because of conversations about end of life and advance-care planning, we had the opportunity to gather around her in her home, to bring her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren around for one last party, sharing memories and prayers. It was clear to me (and to anyone who knew my grandmother) that this was what was important to her. It was what she had chosen; it was her last act as a matriarch to make her own decisions about her death, to take the burden from her family. In the end, those who were there tell me it was the hospice team that eased her burden, making her comfortable and giving those around her permission to let go. If I could give one patient, one family, that gift, it would be my honor.

Resources

Info for Massachusetts families and providers:

Information and links from the Centers for Disease Control (National):

Articles about advance directives in the health care literature:

March 3rd, 2017

Asking Pediatric Patients About Drug Use

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN

Emily F. Moore, RN, MSN, CPNP-PC, CCRN practices pediatric cardiovascular care across the Pacific Northwest.

I remember the very first time I obtained an adolescent HEADSSS assessment in graduate school (HEADSSS being the acronym for Home environment, Education and employment, Eating, peer-related Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicide/depression, and Safety from injury and violence). Walking into my patient’s room, I was likely more nervous than my patient was. I recall telling my preceptor that I doubted anyone would be honest in answering the questions and him saying, “It’s the way you approach the subject.” I still didn’t believe him.

So, imagine my complete surprise when the patient answered my questions with no hesitation. I recall sitting there in utter shock as he riddled me with stories of various drugs he had either taken, snorted, smoked, or injected. My first thought was how to document all of it, rather than how to help him. The other shocking thing was that his mother sat right next to him and didn’t even blink an eye as he told his stories of past drug use.

I realized two things in that moment — first, that my white coat possessed a certain power, and second, that teenagers will really tell you anything if you ask the right questions. Knowing this, I wonder, how do we pediatric clinicians most effectively use this power to better educate our patients and prevent them from using drugs?

One decision we have to make is when to start educating and talking with a patient about drug use. I strongly believe in making it routine to discuss this and other behaviors beginning in the pre-teen years, with parents and teens together, and then again once the parents leave the room. Set an expectation by introducing the HEADSSS assessment early. At this time, an atmosphere of trust and confidentiality can be established, allowing embarrassing topics to be discussed. As the patient gets older, this is already an established part of the visit and will not surprise either the parent or adolescent. The provider can use this time to educate about the risks and dangers involved with opioid use, among other perils adolescents face.

Confidentiality is crucial to emphasize with patients and, in my experience, yields results. I distinctly remember prepping a college-age student for surgery. With her parents in the room, I asked a number of HEADSSS-related questions. Each response seemed perfectly rehearsed; she did not experiment with drugs or alcohol and did not have a boyfriend. I asked her parents to leave the room. They argued, saying they needed to be present. After standing firm and insisting that they leave, I learned a number of things related to drug and alcohol use, boyfriends, and birth control use. This patient stressed that her parents could not find out. She was so adamant about this that she even asked to have her birth control held while in the hospital so that her parents wouldn’t find out. The reality of her situation is all too common.

This brings me to a few thoughts about our role as pediatric providers. Besides delivering anticipatory guidance and counseling against high-risk behaviors to the patient, we should encourage our patients’ parents to talk with their children about it, educating them about how important parental involvement is to preventing adolescent drug use. Beyond that, as a large percentage of our nation’s youth interface with teachers, we should also be getting their input. On more than one occasion I have had a parent come to me concerned about their child’s behavior only to learn that at least one teacher has reported similar worries. As providers, should we be paying extra attention to these reports, even educating parents to be alerted to reports from school about their child’s behavior or academic performance worsening? I think so. This type of concern from a teacher, albeit third-party information, would immediately alert a PCP to assess behaviors, opening the door for treatment and referrals if appropriate.

In a world where opioid use has become an epidemic, I feel strongly that it is a fiduciary duty of mine, as a provider, to constantly be assessing, treating, and educating about the dangers of addiction. We may never understand the power of the white coat, but we can certainly use it to our advantage, providing anticipatory guidance to all patients and the key adults in their lives.

March 1st, 2017

Listening to Bowel Sounds: An Outdated Practice?

Alexandra Godfrey, BSc PT, MS PA-C

Medical programs teach us that listening to bowel sounds is an essential part of the physical examination of the abdomen, especially when the differential includes ileus, small bowel obstruction, diarrhea or constipation. Woe betide the student who fails to auscultate the abdomen of patients with these presentations. Yet firstly there’s little supporting evidence for this maneuver, and secondly there’s a lack of consensus about correct technique. Despite these issues, bowel sounds are claimed to help us develop our differential and cinch our diagnosis. The relationship between bowel sounds and pathology is not evidence based. It appears to be more a reflection of tradition and anecdotal evidence.

The Technique

The noises produced by the movement of gas and fluids during peristalsis are bowel sounds. The technique learned depends on the school, the clinical gut of faculty and staff, and the physical exam text chosen. Some educators teach students that listening in one area is enough whereas others teach them to listen in all four quadrants. Bates’ recommends listening in only one spot, Mosby’s in all four quadrants, and DeGowin’s suggests listening in all four quadrants and the midline. Given that borborygmi may disseminate across the entire abdomen, and what you hear in one quadrant may reflect another part of the abdomen, the precise placement of your stethoscope seems irrelevant.

Also controversial is the duration of auscultation. Educators (and texts) teach students to listen for bowel sounds for anything from 30 seconds to 7 minutes. In reality, a healthy person may have no sounds for several minutes but then later have up to 30 a minute. Bowel sounds may cycle with peak-to-peak periods over 50-60 minutes. This means that any analysis less than that time will be inadequate.1 Additionally, some intestinal contractions are silent, so we cannot presume that a quiet bowel is a motionless bowel.

This complexity is further compounded by order of operations. Schools in the United States teach students to listen prior to palpation whereas schools elsewhere teach students to auscultate after palpation. I was taught to listen in each quadrant for up to 30 seconds or until bowel sounds were heard. This was done prior to palpation. Reversing the procedure was considered unacceptable. The thinking here is that palpation might disturb the intestines, trigger peristalsis, and thus alter the physical exam. My question is — so what?

There’s little evidence to suggest that borborygmi triggered by palpation are any more or less pathological than those that are not. I also suspect that patients might push on their own bellies before a clinician ever enters the room or even in their presence to illustrate their pain: it hurts here!

In researching this issue lately, as I folded page corners of great medical tomes and drew boxes around pertinent information, I felt that I might do just as well turning those pages into something tangible, relevant and concrete; something akin to the Japanese art of origami – a model of bird’s beak esophagus perhaps.

The Evidence

A friend and colleague of mine who trained as a surgeon in South Africa in the 1970’s described to me his memories of learning the nuances of borborygmi. Back then, this was their art.

“When I trained, and did a lot of intestinal surgery, borborygmi really meant being able to hear loud bowel sounds without a stethoscope. We learned to listen for those differences that depict ileus from mechanical intestinal obstruction, an important distinction since the mechanical obstruction often needed an urgent operation while ileus did not; we learned to distinguish propulsive sounds from ‘tinkling,’ non-propulsive ones. I got quite good at that as a chief registrar in Johannesburg. My teachers and the master clinicians who taught me, translated bowel sounds into action. Propulsion — operate! Tinkling — don’t operate!”

The most common and urgent reason to listen to bowel sounds is small bowel obstruction (SBO). The instruction is that bowel sounds will be hyperactive or absent in the setting of SBO. This is the time when the diligent clinician should wield their scope, placing the diaphragm below the diaphragm. However, in a recent study, 53 doctors used a Littman’s electronic stethoscope to assess the bowel sounds of patients with and without SBO. The median frequency with which doctors classified borborygmi as abnormal did not differ significantly between patients with and without bowel obstruction (26% vs. 23%, P=0.08). The study concluded that auscultation of the abdomen provided little help when making clinical decisions regarding management.2

A study published in The Journal of Surgical Education in 2010 came to similar conclusions. They found that “listeners frequently arrive at the incorrect diagnosis.” Listeners were unable to accurately characterise bowel sounds as normal, SBO or ileus. They also noted no difference in accuracy between surgical and internal medicine residents. They concluded that listening to bowel sounds is not a clinically useful part of the physical exam.3

Another reason to listen to bowel sounds is ileus. A study in 2012 examined the utility of listening to bowel sounds as a method of determining the end of post-operative ileus. This study determined that there was no association between the finding of bowel sounds and the return of bowel activity. This research concludes that routine assessment of bowel sounds for resolution of ileus is according to an outdated and unnecessary procedure.4 Undeniably, patients with ileus and SBO often do have abnormal bowel sounds, but it appears that listening for them has little utility in clinical practice today.

The Conclusion

I am a keen supporter of the history and physical exam. I advocate for the use of hands, ears and eyes. However, clinicians must be progressive, embracing new modalities and letting go of less reliable methods. For example, teaching bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of SBO might be a better use of time. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic modalities used to identify SBO found ultrasound to be superior to all other modalities.5

It is unlikely that medical, nursing and physician assistant programs will stop teaching students to listen for borborygmi any time soon. I hope though that the lack of both evidence and standardisation will at least encourage students, educators and clinicians to question the efficacy and utility of this maneuver. No one should fault the clinicians of earlier times; they lacked the technology and data we have today. Some might consider auscultating for bowel sounds as another part of our arsenal for deployment, rather like Homans’s sign for deep vein thrombosis: something to pull out of our medical tool bag when diagnostic resources are scarce – when our scope is all we have. That said, given the lack of consensus and supporting evidence, I believe patients might benefit more from the ancient art of origami than borborygmi. At least the former might soothe the patient.

1) McGee, S, Evidence-Based Physical Diagnosis, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier-Saunders; 2012

2) Breum BM, Rud B, Kirkegaard T, Nordentoft T. Accuracy of abdominal auscultation for bowel obstruction. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2015;21(34):10018-10024. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.10018.

3) Felder S, Margel D, Murrell Z , Fleshner P. Usefulness of Bowel Sound Auscultation: A Prospective Evaluation. Journal of Surgical Education, 2014-09-01, Volume 71, Issue 5, Pages 768-773.

4) Massey R. Return of bowel sounds indicating an end of postoperative ileus: is it time to cease this long-standing nursing tradition? Medsurg Nursing, 2012-05, Volume 21, Issue 3, Page 146 -150

5) Taylor N, Lalani M. Adult Small Bowel Obstruction. Journal of the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine,5) 2013-06-12, Volume 20, Issue 6, Pages 527-544

February 24th, 2017

Deep Brain Stimulation Targeting in Neurosurgery, Part I of III

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

This three-part series is for providers who lack an intimate level of knowledge and/or experience with deep brain stimulation (DBS) targeting. My goal is to provide a baseline understanding of each target, its indications, contraindications, and adverse side effects that may be observed from imperfect electrode placement and/or imperfect programming.

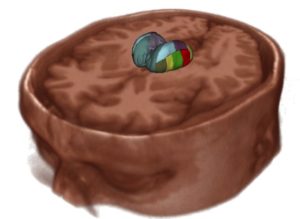

Specifically, I will discuss the basics regarding the three most frequently used DBS surgical targets for Parkinson’s disease (PD), dystonia, and essential tremor (ET): the ventralis intermedius (Vim) nucleus of the thalamus, globus pallidus internus (GPi), and the subthalamic nucleus (STN).

This first post will focus on the Vim.

I’ll start by briefly describing deep brain stimulation. DBS has become a commonly used and well-known surgical intervention for the treatment of medically refractory movement disorders such as PD, dystonia, and ET. The intervention involves the implantation of unilateral or bilateral electrodes that provide chronic stimulation into the deep brain at one of the aforementioned targets. The electrodes receive power from a battery-powered simulator that is typically implanted in the chest just beneath the skin and a couple of inches below the clavicle. The entire DBS system, including connecting wires, resides under the skin. We aren’t exactly sure of how DBS works, but some think that the mechanism of action is consistent with the blocking of neuronal signals transmitted through the stimulated structure and desynchronization of abnormal oscillations [1, 2].

It is important to note that DBS programming is an art form and requires a team effort. It isn’t something you just turn on and off. It requires a good knowledge of anatomy and the equipment’s capabilities. Although programmers (typically neurologists, neurosurgeons, or PAs and NPs who work in those settings) get better with experience, every patient is a little different, thus requiring finesse and good communication within the DBS team to combat programming troubles. High-volume centers generally have good working relationships between the neurology, neurosurgical, and neuropsychiatry teams for the purpose of achieving the best patient outcomes in the face of these challenges. The neurosurgery team handles the electrode placement and then communicates that placement to the programming team to give them an idea of how to start programming. Aside from proper patient selection, it is helpful to set patient expectations prior to surgical intervention. DBS is not a cure for any disease, though for many, it can significantly improve quality of life by treating their symptoms.

Ventralis Intermedius (Vim)

Where is it located?

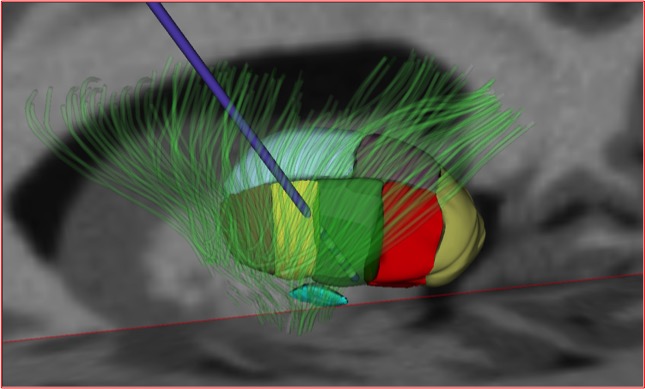

Vim (green). Subthalamic nucleus (turquoise, below VIM). (Reprinted with the permission of Medtronic, Inc. © 2017)

The ventralis intermedius is located on the ventral aspect of the lateral thalamus.

Indication:

- Tremor – Vim stimulation has been shown to be as effective as a thalamotomy but with fewer adverse side effects. Although it has excellent anti-tremor effects, it does not show the same effectiveness on other prominent parkinsonian symptoms such as bradykinesia and rigidity. For this reason, it is most commonly targeted in essential tremor and not Parkinson’s disease.

Contraindication:

- There is no glaring contraindication to the selection of this target; however, as mentioned before, it isn’t the first choice for patients with PD, and since dystonia does not have a tremor component, Vim is not an appropriate choice for dystonia.

Stimulation adverse side effects based on location of electrode in relation to optimal placement [3]:

- Too lateral: With stimulation of the internal capsule, effects consist of muscular contractions and dysarthria.

- Too medial: Potential speech and swallowing issues

- Too posterior: With stimulation of the ventral caudal nucleus, effects consist of persistent paresthesias

- Evoking paresthesias during the programming process is not abnormal in itself, but the patient will habituate – they should not be persistent.

- Too anterior: Suboptimal tremor reduction at typical voltages

- May need higher voltage to attain good control, which requires more frequent battery changes

- Too superior: No effect on tremor

- Too deep: A range of side effects depending on how deep, ranging from no effect on the tremor to ataxia and muscle contractions

In Part II of this series, I will address selection of the globus pallidus internus (GPi) as the DBS target.

References

- Benazzouz A, H.M., Mechanism of action of deep brain stimulation. Neurology, 2000. 55 (12 Supplement 6).

- Ashby P, R.J., Neurophysiologic aspects of deep brain stimulation. Neurology, 2000. 55 (12 Supplemental): p. 17-20.

- DBS Anatomy & Side Effects. A Presentation by Kirk Finnis, PhD. Medtronic.

February 13th, 2017

What’s Your Sign(out)?

Harrison Reed, PA-C

My house is a disaster zone. After working a string of 12-hour shifts, there is a mountain of dishes in the sink and a minefield of dirty clothes on the floor. As I navigate that post-apocalyptic landscape, my mind tends to wander back to the hospital I just left. I sometimes pause on the small victories, sure, but more often I find myself focused on all of the potential improvements.

I’ve noticed that the flavor of reflection often depends on my very last interaction of the day. For shift work in the ICU, that means sign-out: the ritual of passing pertinent patient information from one clinician to the next. There’s a reason it feels like that single act can make or break a shift. Because it can.

Sign-out can be a stressful time for medical providers and a dangerous time for patients. Every transition of patient care presents a chance for effective communication or an information fumble. It can be the difference between a missed diagnosis and a brilliant save. It can mean success or failure.

There might not be a single perfect method of sign-out, but there are key concepts to keep in mind and pitfalls to avoid. I offer some here:

Find a system: A little organization goes a long way toward ensuring a safe sign-out process. Variation between clinicians is O.K. as long as everyone provides information in a logical fashion.

Some teams and hospitals, particularly large-volume academic centers that feature many individual hand-offs in a given day, have developed standardized systems to assist in the sign-out process. At least one randomized crossover study suggests that a computerized system can save time and might improve patient care.

Allow Questions: The absent smile, the slow nod. The glazed-over eyes that stare right through you. If you see these signs, chances are you’ve lost your audience. It happens more than we like to admit and is a sure-fire way to miss important information. It’s also the reason sign-out should be a safe place for both parties to ask questions and seek clarification.

Of course, how and when we ask questions is just as important. Avoid confrontational language or tone and try to limit interruptions. A good sign-out should sound more like a dialogue than an interrogation.

Lose the Retrospectoscope: It’s tempting to become a sports analyst during sign-out, to look at information and retrospectively judge the decisions of our predecessors. Of course, that kind of glaring hindsight bias is unfair to our colleagues, especially if we don’t have a complete understanding of the context of those decisions. A harsh critic on the receiving end of sign-out will only hamper communication and may foster an environment of animosity rather than an open and honest exchange of information.

Avoid Anchoring: In an effort to give a complete sign-out, we often include our opinion, theories, and clinical judgment in the information we pass on to our colleagues. It makes sense to summarize our conclusions and attach a diagnosis or prognosis to the patients for whom we cared. Why make our counterparts reinvent the wheel, right?

Unfortunately, this habit anchors our colleagues’ brains to our ideas and negates much of the benefit of having a fresh set of eyes on a problem. We may unintentionally influence them to ignore signs that would otherwise prompt a workup, or to stick to a particular treatment plan despite an evolving clinical situation. Even if we are conscious of these risks, once an idea is planted in a colleague’s mind, it will continue to exert subconscious bias on future decisions. An idea can be as contagious as a virus.

Sign-out is a great time to take a step back and reexamine possibilities that might have been dismissed. It is an opportunity to open up the differential diagnosis, however briefly, and acknowledge alternative possibilities. This doesn’t mean we should start every workup from scratch. But we should maintain the same skepticism that we would apply to a new patient. Besides, if two clinicians still reach the same conclusion, they are much more likely to be on the right track.

Sign-out is a great time to take a step back and reexamine possibilities that might have been dismissed. It is an opportunity to open up the differential diagnosis, however briefly, and acknowledge alternative possibilities. This doesn’t mean we should start every workup from scratch. But we should maintain the same skepticism that we would apply to a new patient. Besides, if two clinicians still reach the same conclusion, they are much more likely to be on the right track.

Of course, this concept is not restricted to the world of diagnosis. It’s just as dangerous to transmit other judgments about our patients. If we say a patient is mean or rude, we have set up our coworkers to be less empathetic toward that person. If we dismiss someone as “just a little crazy,” the next caregiver could miss important signs of withdrawal or intracranial hemorrhage. The negative effects of cognitive bias are dangerous enough without passing them on to the next shift.

There are many great ways to improve clinical sign-out. Please leave yours in the comment section below.

February 8th, 2017

Want to Work Abroad?

Megan Tetlow, PA-C

Megan Tetlow, PA-C, is from Fort Myers, Florida, now working in Sheffield, England, as part of the National Physician Associate Expansion Program. She practices in gynecologic oncology and is a guest blogger for In Practice.

Have you ever thought about working abroad? Maybe like me you’ve always daydreamed about living and working in another country, maybe you’re hungry for a new experience, or perhaps recent political news in the U.S. has you googling the feasibility of moving to Canada. Regardless of your motivations, for those individuals motivated and willing to do the legwork (and paperwork! I’m not going to lie, there’s quite a bit of paperwork.), it is possible to work outside of the good old U.S. of A. Today, I would like to share some of the potential avenues for American physician assistants interested in working abroad.

While the U.S. has by far the largest PA workforce (over 100,000 proudly certified PAs!), other countries are trialing and adopting the PA role in their own health systems. I currently practice in England as part of the National Physician Associate Exchange Program, a two-year program to expand the role of PAs in the National Health Service in England. A colleague of mine participated in a similar program in Scotland. Australia and New Zealand both have conducted similar trials investigating the PA role and how it could be integrated. Closer to home, Canada has a growing PA workforce, and American PAs that have graduated from an ARC (Accreditation Review Commission)-accredited PA program and are certified by the NCCPA (National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants) are eligible to take the Canadian PA Certification Exam. Other countries that employ PAs include Northern Ireland, Wales, the Netherlands, South Africa, Ghana, and India (let me know in the comments if I’m missing anyone!).

Another path for American PAs to work abroad is via a post through the U.S. government. Several federal organizations employ PAs and other healthcare practitioners to provide medical care while their employees are abroad. The U.S. Armed Forces employs civilian PAs to provide care to members of the military and their families on bases both in the U.S. and overseas. Continuing in the vein of government employment, the U.S. State Department hires PAs as Foreign Service medical providers to provide primary care and preventive health services to state department employees and their families. These posts are usually carried out on two-year overseas tours in a wide variety of locations across the globe.

Another path for American PAs to work abroad is via a post through the U.S. government. Several federal organizations employ PAs and other healthcare practitioners to provide medical care while their employees are abroad. The U.S. Armed Forces employs civilian PAs to provide care to members of the military and their families on bases both in the U.S. and overseas. Continuing in the vein of government employment, the U.S. State Department hires PAs as Foreign Service medical providers to provide primary care and preventive health services to state department employees and their families. These posts are usually carried out on two-year overseas tours in a wide variety of locations across the globe.

The possibility of working for NGOs and other aid organizations also should not be overlooked. Organizations such as the Peace Corps employ PAs as medical officers. In this role you would be providing medical care to Peace Corps volunteers both within the U.S. and abroad. Additionally, various private companies, research groups, and contract firms employ PAs to support their employees all over the world, from Nepal to Antarctica (bring your mittens!).

Also, while not technically abroad, another option for American PAs is working in a U.S. territory. For example, PAs can work in both Guam in the Western Pacific and in the U.S. Virgin Islands in the Caribbean. Family practice on  Friday, snorkeling and piña coladas in St John’s on Saturday? Yes, please.

Friday, snorkeling and piña coladas in St John’s on Saturday? Yes, please.

Finally, there are many avenues for volunteerism abroad as a PA, in both secular and religiously affiliated roles, with both short-term and long-term options. The Peace Corps welcomes PAs and other healthcare provider volunteers in a number of opportunities in community and public health on two-year tours. There are dozens of groups and charities that coordinate shorter-term volunteer work abroad as well (mention any you are aware of or happen to work for in the comments!). PAs for Global Health, a nonprofit organization for PAs interested in volunteering in medically underserved areas around the world, has numerous resources for PAs interested in medical volunteerism abroad.

The road to working abroad is not always easy. There are frustrations and crossed wires, cultural differences, and paperwork — always paperwork. But for those with a will to work abroad and an open mind, it is also an incredibly rewarding experience that I am so grateful to be having. If you have an interest, I encourage you to seek out a similar opportunity. Please see the resources below for more information. Until next time, cheers!

Resources:

1. National Physician Associate Exchange Programme

2. The Faculty of Physician Associates (UK)

3. Canadian Association of Physician Assistants

4. Openings for civilians within the U.S. Military

5. U.S. State Department Foreign Service Medical Providers

6. Peace Corps