October 12th, 2016

Intracranial Aneurysms for the Non-Neurosurgical Provider: Primer Series (Part 1)

Bianca Belcher, MPH, PA-C

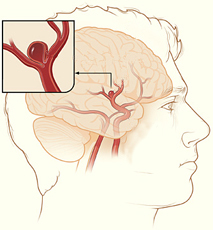

Intracranial aneurysms are unnerving, but not all aneurysms are created equally. It’s no secret that nearly 50% of people with intracranial aneurysm ruptures die before they get to the hospital, and of the 50% who make it to the hospital, about 30% die despite our best efforts. Our office often gets urgent referrals from non-neurosurgical offices for incidentally found aneurysms that were discovered during workups for chief complaints such as dizziness or headache. Not all aneurysms are life threatening, and not all need an immediate referral to the emergency department; some just need monitoring by a provider who treats aneurysms on a regular basis.

In this series of three primers on intracranial aneurysms, I will review the following: 1) the International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms (ISUIA), 2) Patient Risk Factors, and 3) Treatment Options 101. The point of this series isn’t to create experts, but instead, to help non-neuro providers gain a better understanding of the neurosurgical thought process when considering next steps for these patients.

In this series of three primers on intracranial aneurysms, I will review the following: 1) the International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms (ISUIA), 2) Patient Risk Factors, and 3) Treatment Options 101. The point of this series isn’t to create experts, but instead, to help non-neuro providers gain a better understanding of the neurosurgical thought process when considering next steps for these patients.

The International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms (ISUIA) is probably one of the best natural history studies we have on aneurysms to date. There are two phases of ISUIA. Phase 1 (1998) was a two-part study: Part A, the retrospective arm, focused on the natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. It looked at patients with and without history of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and determined if there were subgroups of people at elevated risk of rupture. In Part B, the prospective arm, the researchers primarily aimed to evaluate morbidity and mortality risks associated with treatment of unruptured aneurysms. Phase 2 (2003) was a prospective study that looked at the natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms as well as clinical outcomes and associated risks of aneurysm treatment, both endovascular and surgical. For the purposes of this blog, I will only focus on the natural history portions of each study (Phase 1, the retrospective arm, and Phase 2, natural history data).

Phase 1(1998) – ISUIA Retrospective Study

Overview:

- 53 centers (US, Canada, Europe)

- 1,449 patients, 1,937 aneurysms

- Group 1 (no history of SAH): 727

- Group 2 (history of SAH from a different aneurysm): 722

- Mean follow up: 8.3 years

- Aneurysm size groupings (<10 mm, 10–24 mm, ≥25 mm)

- Study strengths: large number of aneurysms, multi-center

- Study weaknesses: retrospective, potential for selection bias

Outcomes:

- 32 of 1,449 patients had confirmed aneurysm ruptures

- Group 1 ruptures (12/32): 11 in aneurysms ≥10 mm, 1 in aneurysm <10 mm

- Group 2 ruptures (20/32): 3 had aneurysms ≥10 mm, 17 had aneurysm <10 mm

- Relative risks of rupture by location of aneurysm (as compared to other locations)

- Group 1:

- 13.8 for basilar tip

- 13.6 for vertebrobasilar /posterior circulation

- 8.0 for posterior communicating (PCom) artery

- Group 2:

- 5.1 for basilar tip

- Group 1:

- Annual risk of rupture by size of aneurysm

- Group 1:

- <10 mm: 0.05%

- 10–24 mm: 1.0%

- ≥25 mm: 6.0%

- Group 2:

- <10 mm: 0.5%

- 10–24 mm: 1.0%

- ≥25 mm: not enough patients to calculate (n=3)

- Group 1:

- Significant predictors of rupture:

- Group 1: size and location of aneurysm

- Group 2: location of aneurysm and older patient age (RR, 1.31)

Phase 2 (2003) – ISUIA Prospective Study

Overview:

- 61 centers (US, Canada, Europe)

- 4,060 patients (1,692 no intervention [natural history], 2,368 underwent treatment)

- 2,686 aneurysms

- Group 1 (natural history cohort; no history of SAH): 1,077

- Group 2 (natural history cohort; history of SAH from a different aneurysm): 615

- Mean follow-up: 4.1 years

- Study strengths: prospective, multi-center, large number of aneurysms

- Study weaknesses: non-randomized, short follow-up period

Outcomes:

- 51 of 1,692 patients had confirmed aneurysm ruptures

- Group 1 ruptures (41/51): 2 aneurysms <7 mm, 5 aneurysms 7–9 mm

- Group 2 ruptures (10/51): 8 aneurysms <10 mm, 2 aneurysms ≥10 mm

- Cavernous carotid artery and anterior circulation aneurysms <7 mm in those patients without a history of SAH had a 0% risk of rupture.

- Cavernous carotid artery aneurysms <13 mm, regardless of history of SAH, had a 0% risk of rupture.

- Anterior circulation and posterior circulation aneurysms 7–12 mm had 5-year cumulative rupture rates of 3% and 15%, respectively.

Another relevant study:

One of the more recent studies being discussed in the cerebrovascular care community is out of Japan, The Unruptured Cerebral Aneurysm Study of Japan (UCAS Japan) 2012 (5,720 patients, 6,697 aneurysms). Unlike the ISUIA Phase 2, UCAS authors assessed an annual rupture rate (0.95%) as opposed to a 5-year rate and considered treatment for aneurysms that are ≥5 mm, as opposed to ≥7 mm in ISUIA. In another difference, UCAS authors found that non-smooth aneurysms (those with daughter domes) have a higher rupture rate compared with smooth aneurysms. Lastly, with regard to location, UCAS results show higher risk of rupture in both the ACom and PCom regions, whereas ISUIA identifies higher rupture rates only in the posterior circulation. The downside to this study is its limited generalizability outside of the Japanese population, who have a higher risk for subarachnoid hemorrhage than other populations.

Key Takeaways:

- ISUIA offers a good place to start the “treat or monitor” discussion. Although it’s an older study, ISUIA is probably one of the best/largest studies with respect to natural history of aneurysms and one that we quote to patients frequently. Don’t get me wrong; it’s not a perfect study. There are criticisms of the study design and likely some selection bias involved, but both phases of ISUIA still hold value.

- If you were to consider only aneurysm size/location/prior history of rupture, aneurysm treatment is considered if one or more of the following circumstances is met:

- Size is ≥5 mm

- Location in the posterior circulation or ACom artery

- Patient has a prior history of cerebral aneurysm rupture

- Aneurysm has an odd, non-smooth morphology (daughter domes)

- Aneurysm changes in shape or size between interval imaging

- Patients with a prior history of SAH are 10 times more likely to have rupture (of aneurysms <10 mm) than a patient without a history of SAH, though it is important to note that the annual rupture rate still remains relatively low in patients with a prior history at 0.5% per year.

- Cavernous aneurysms rarely rupture unless they are giant. Important note: True cavernous aneurysms are not located in the dura. They are located in the cavernous sinus, meaning that if they rupture, they do not cause SAH and are unlikely to kill your patient. Ruptures present as carotid-cavernous fistulas (CCF) with symptoms such as exophthalmos, ocular motor palsy (3rd or 6th depending on the directionality), and vision problems. If you suspect a cavernous aneurysm rupture, the patient needs to be seen by a cerebrovascular surgeon/neurointerventionalist quickly. Any cranial nerve symptoms that are secondary to the CCF can become permanent if it is not treated soon after rupture.

In Part 2, I will present modifiable and non-modifiable patient risk factors with regard to intracranial aneurysm treatment considerations.

References

The International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: Risk of rupture and risks of surgical intervention. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:1725.

Wiebers DO et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: Natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet 2003; 362:103.

The UCAS Japan Investigators. The Unruptured Cerebral Aneurysm Study of Japan (UCAS Japan). N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2474.

Helpful to non-neurosurgeons.

Are there any traits/symptoms that make one more likely to have an aneurism? FH I presume stands high.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease is the big one.

This is a great guide, although I think it is a bit remiss that neuroradiologists and vascular neurologists are not identified as providers as well.

The PHASES score by Backes et al is also useful reading!

Thank you for this excellent overview. I would like to hear more about the risks associated with neurosurgical intervention for aneurysms, especially those discovered incidentally or through screening first degree relatives of patients with ruptured IAs.

Thank you for the comment. I hope you had a chance to review the Part 2 on risk factors. Part 3 on treatment options will be coming out very soon. Best,Bianca