An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

December 6th, 2010

Tough Diagnoses: Neurosyphilis, Then and Now

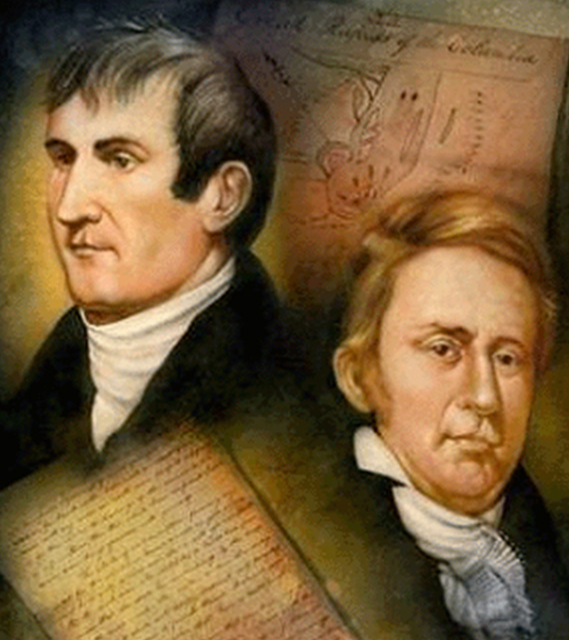

During Thanksgiving, my brother-in-law — who is a professional musician and also a passionate history buff — gave me a scholarly paper to review on the strange death of the famous American explorer Meriwether Lewis, of “Lewis and Clark” fame.

During Thanksgiving, my brother-in-law — who is a professional musician and also a passionate history buff — gave me a scholarly paper to review on the strange death of the famous American explorer Meriwether Lewis, of “Lewis and Clark” fame.

The bottom line? Lewis may well have had neurosyphilis — at least that’s the premise of the epidemiologist Reimert Thorolf Ravenholt, who, in a nearly 13,000 word report, ultimately concludes:

The fabric of evidence that syphilis acquired during the explorative trip to the Pacific Coast was the underlying cause of Lewis’s death includes these threads: (1) Lewis was in excellent health when he set forth up the Missouri River; (2) several Indian tribes suffering from syphilis were encountered; (3) sexual intercourse with women of these tribes by Corps members was frequently urged by the Indians and was commonplace; (4) several Corps members (probably at least eight) did develop syphilis; (5) when encountering the Shoshoni tribe on the Continental Divide, Lewis had both a propitious opportunity and a compelling need for sexual intercourse; (6) a few weeks later, he developed illness which became severe and disabling for several months, but the nature of which was not described; (7) for some months in 1807, following his return from the expedition, he was incapacitated by illness, the nature of which was not divulged; (8) during 1808-809, he developed progressive illness afflicting his central nervous system and diminishing his judgment faculties; (9) his terminal months in 1809 were characterized by progressive, episodic, febrile illness, with severe mental and behavioral disorders highly characteristic of paresis; (10) Lewis himself recognized that he was suffering from a progressive disease likely to be fatal; (11) Thomas Jefferson and William Clark readily understood why his death was a probable act of self destruction.

Emphatically not the Lewis and Clark story I learned in 5th Grade!

But sure, the diagnosis of neurosyphilis sounds plausible. Sexual indiscretion followed by rashes followed by a progressive neurologic disease with increasingly bizarre and unreliable behavior. (Not so sure about the fever part.)

But while these speculative diagnoses are fascinating both historically and medically (Mozart’s death has 325 citations in PubMed), one inevitably gets back to the problem of confirming the diagnosis, which is almost always impossible.

Furthermore, there are several reasons why neurosyphilis is in particular a difficult diagnosis to prove, even today, including:

- Protean symptoms that wax and wane.

- Variable latency period.

- Relatively uncommon, especially since the discovery of penicillin.

- Unreliable diagnostic testing and no readily available culture.

- Clinical and lab-based manifestations have significant overlap with other diseases.

- Lots of what was called neurosyphilis back in the day probably was something else, making much of the clinical teaching about the disease highly subjective.

In fact, with the exception of obvious cases — ocular disease concurrent with secondary syphilis, or CSF pleocytosis and positive VDRL in the setting of a classic clinical presentation — it otherwise seems that the diagnosis of neurosyphilis is made only after an esteemed clinician definitively, confidently, and loudly states THIS IS NEUROSYPHILIS.

Especially if that clinician has a certain well-aged gravitas.

Dr. David Peck, author of Or Perish in the Attempt; Wilderness Medicine in the Lewis & Clark Expedition, Farcountry Press, 2002, wasn’t sold by the purported neurosyphilis diagnosis. Peck’s work analyzes the state of medicine at the time and medical issues such as infectious diseases with which the expedition dealt, including Lewis’ purported neurosyphilis.

Peck, citing Edmund C. Tramont in Mandel et al.’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, notes that neurosyphilis mimics “any degenerative neurologic process, or disorder that can cause chronic inflammation (e.g., tuberculosis, fungal or sarcoid meningitis, tumors, subdural hematoma, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, chronic alcoholism), or any disorder affecting the vasculature of the central nervous system. The axiom that syphilis can mimic any disease is particularly apropos with regard to the central nervous system.”

Would be glad to share the book with you if you would like.

I think you’re approaching this from a contemporary medical perspective. Obviously, you can’t make a definitive diagnosis based on the information available. But we’re dealing in the realm of historical speculation. I can’t draw a conclusion based on medical training that I don’t have but I can look at the evidence the way a juror would and I think from that perspective Ravenholt makes a very good case. The important historical question, and the one that’s been either glossed over or ignored by nearly all historians writing about the L&C expedition, is what accounts for Lewis’s drastic personality change and his subsequent deterioration. Before the expedition Jefferson considered him the most excellent young man in the republic. By 1806 he would have nothing to do with him.

I did check out the Peck book Artie Bootle cites on Amazon and read the comments. I also perused the book on Google Books. Peck does list Ravenholt as a source ( page 299) in the index but his arguments against Ravenholt’s diagnosis seem weak to me.

My point is this: even in the realm of “historical speculation” — which you are right you can’t generally prove a diagnosis — neurosyphilis would be a tough one to nail down with any certainty. There are simply too many other things that mimic these symptoms, and as I mention, even today it’s far from straightforward who has it and who doesn’t.

By contrast, the historical figure who gradually wastes away, periodically coughing up blood and becoming progressively pale — he/she probably did have tuberculosis!