An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

January 22nd, 2017

Fun With Old Medical Images!

Welcome to Fun with Old Medical Images!

Here’s how it works: You’ll see a series of images — old, strange, and perplexing — and each will have a caption that I have created for you at no extra cost.

Accustomed to high-quality and clinically relevant information from your NEJM Journal Watch contributors, you will laugh happily at the contrast between that solid content and this silly exercise, forgetting for a moment the complicated and sometimes contentious world we live in.

See, this will be therapeutic.

Off we go. Here’s the first one:

“Perkins wondered whether his doctors might consider an alternative treatment for his migraines, as the heated box on his knee appeared to be ineffective.”

Poor Perkins! I’m sure he’s also wondering why his doctors didn’t give him a pillow.

That was fun. Ready for #2?

“Drug development of the novel sleep aid was halted when many patients reported lethargy, fatigue, and vivid dreams of milk, eggs, and lamb chops.”

So many promising drugs fail during clinical trials due to side effects! At least dreaming of lamb chops is safer than QT prolongation.

Now, onto #3:

Such stillness in that room! And who’s the uniformed man in the upper right? Is he a scribe?

We’re on a roll! Here’s #4:

That’s one smart girl — she reads the literature! And she knows for a fact that Andrew Wakefield (not in this picture) is a fraud.

The laughs keep coming, so let’s go on to #5:

Here the key question — did medical insurance in mid-19th century France cover the cost of Uber for housecalls? I did a quick search — fascinating result.

Should we finish with a neat half-dozen? Why not, here’s #6:

“Patients were thrilled with the new device, which both measured intraocular pressure and gave a quick hair blowout.”

Nothing but fun at this ophthalmologist’s office! Eye appointments always last too long, so why not get checked for glaucoma and get a bit more stylish at the same time?

Thank you for taking this tour of Old Medical Images, I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did.

Next time, we’ll go back to our usual programming.

January 16th, 2017

Two Case Reports Worth Reading, and Enlisting Pro-Vaccine Support

Case reports are pretty low down on the “levels of evidence” pyramid. This low status notwithstanding, when they are well done they can illustrate important clinical lessons, including these two:

Case reports are pretty low down on the “levels of evidence” pyramid. This low status notwithstanding, when they are well done they can illustrate important clinical lessons, including these two:

- A Las Vegas woman died after infection with a pan-resistant strain of Klebsiella. While CDC receives many isolates of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE), 80% are susceptible to at least one aminoglycoside and 90% to tigecycline — not this one, which retained susceptibility only to fosfomycin (a drug not available in this country for systemic use). One critical detail in this case was her multiple recent hospitalizations in India related to a right femur fracture and osteomyelitis of the right femur and hip. As with this case of metronidazole-resistant Bacteroides, the travel appears to be the critical exposure history. Question for those who practice in a Travel Clinic — do you now counsel patients about their risks of acquiring highly resistant organisms during travel to certain countries? Seems this risk is particularly high with travel to Southern Asia — probably higher than many of the more exotic conditions that get more attention.

- A man experienced a delayed diagnosis of TB meningitis due to a false-positive multiplex PCR. A 75-year-old man presented with mental status changes, and the BioFire FilmArray on the CSF was positive for HSV-1. Herpes encephalitis, case closed, right? However, the ultimate diagnosis was tuberculous meningitis, and the HSV-1 was not confirmed by additional PCR testing using another FDA-approved assay. Of course in hindsight, it seems clear that this wasn’t clinically consistent with HSV-1 encephalitis, FilmArray result notwithstanding — onset of confusion and speech difficulties was gradual, not acute; an MRI showed no parenchymal abnormalities, unusual in someone with HSV-1 encephalitis of this duration and severity; there was a neutrophilic pleocytosis and markedly elevated CSF protein; he developed hydrocephalus. Individually, several of these could rarely be seen with HSV-1 encephalitis, but together along with his clinical worsening they appropriately raised the concern that the diagnosis was incorrect. Of course hindsight is 20-20, and the most important message in this case is not to succumb to “premature closure” if the clinical picture does not fit the lab test result — an especially important lesson with new testing modalities.

Now, to enlist your support for vaccines, for which there is the highest level of evidence for efficacy and safety. At the kind invitation of Carey Goldberg, the skillful editor of WBUR’s CommonHealth blog, I wrote a piece about the possible appointment of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. by Trump to lead a commission on vaccine safety and scientific integrity.

Kennedy, you may be aware, has a lengthy history of pushing anti-vaccine propaganda.

To you, loyal readers of an ID/HIV blog, I am going to state with 99.9% confidence that you will agree with my views — but please read the piece anyway. This debate about the risks and benefits of childhood immunizations is still (amazingly), a thing — just read the comments if you can stand it — and we need all the support we can get.

But I have a query. Here’s the NPR Facebook page on the piece, with one section highlighted for discussion:

Not sure exactly what they meant by “oddly delightful”, but I’m pretty sure it’s better than the converse — “delightfully odd.”

Happy MLK Day.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cuAl5cMTJ7A&w=560&h=315]

January 8th, 2017

Poll: Should Medicine and Family Practice Residency Programs Have a Dedicated HIV Track?

A few medicine and family practice residency programs around the country have a dedicated track that focuses on HIV care. Though the programs naturally differ somewhat in structure — here are two examples from University of Washington and Yale — they generally involve placing the resident into an HIV clinic for their longitudinal outpatient experience.

We don’t have such a program here, though I’ve been asked about it several times over the years. I can certainly think of advantages and disadvantages to this specialized track.

And since we’re in the midst of residency interview season — plenty of young, bright people wandering around the hospital in dark suits they might not wear again for a couple of years — it seems a good time to consider the issue.

On the plus side for the HIV track:

- Residents with a stated interest in HIV care can get a head start on their career choice.

- There’s a projected shortage of HIV clinicians, and this training will help provide a capable and interested group of young doctors in the field. Residents can skip specialty training in ID and transition right to primary care with a panel of HIV patients.

- Under current training standards, program directors report a high proportion of internal medicine residency graduates are not adequately trained to provide primary HIV care.

- People with HIV are more likely to be poor, from minority or other traditionally marginalized communities (gay men or people with addiction), and having more clinicians sensitive to their needs certainly is a plus.

On the minus side:

- A focused HIV track arguably limits both the breadth of patient experiences and the ambulatory clinical challenges for the resident. Shouldn’t residents get as broad an education as possible at this early stage of their training? This is especially important if they change their minds and choose to do something else.

- If there’s going to be an HIV track, why aren’t there specialty tracks for other diseases? How about more common conditions, such as the primary care needs of cancer survivors, or people with mental illness, or diabetes? Or to choose a couple of problems with comparable numbers in the USA to HIV — how about adults with congenital heart disease, or those with lupus?

- Since so many patients with HIV today are completely stable from the HIV perspective, a dedicated HIV track isn’t necessary. The focus of residency should be learning how to manage problems of aging (hypertension, diabetes, COPD, cancer screening) since these are the most important issues for many HIV patients anyway. Data are emerging that a primary care/specialty collaboration works well — here’s a good recent paper evaluating this issue.

- Doctors who want to manage the most complex HIV issues — multi-class resistance, knotty metabolic abnormalities, opportunistic infections, challenging drug interactions — should do additional subspecialty training Infectious Diseases. In most clinical settings, these situations would prompt a specialty referral regardless of how a resident was trained.

I’m not going to pretend to have the answer to this one. That’s why there’s a poll, and the comments section!

December 25th, 2016

Ebola Vaccine, a New Use for Listerine, USPSTF on HSV, Nether Grooming, and More: A Christmas and Hanukkah Overlap ID Link-o-Rama

A few notable ID stories out there for this remarkable convergence in our Judeo-Christian holiday calendar:

- Experimental Ebola vaccine “100%” effective. Impressive scientific progress on prevention of this terrifying disease, with even better strategies expected soon.

- 10 days of antibiotics is better than 5 for childhood (age < 2) otitis media. For the record, my “inside source” on this question is not surprised one bit at the result. We’re seeing the opposite trend in sinusitis and pneumonia treatments of adults, toward shorter antibiotic courses.

- The USPSTF recommends against routine serologic screening for genital herpes. The serologic test is lousy, with lots of false positives — from the summary: “The positive predictive value may be as low as 75% for the biokit test and as low as 50% for HerpeSelect.” As I’ve noted before, the recommendation against general screening probably won’t apply to patients who come in requesting to be tested, where you can explain the pros and cons of the strategy.

- The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association risk calculator discriminates cardiovascular risk “adequately” in people with HIV. Adding HIV-specific factors (HIV viral load, CD4 lymphocyte count, antiretroviral therapy, and protease inhibitor use) to the calculator did not improve the performance. A take away point is that at the lower estimates, these should be considered the minimum risk.

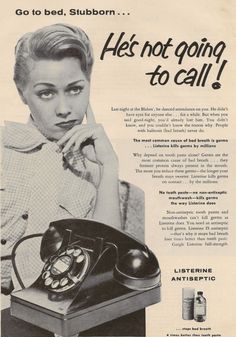

- Listerine is active against pharyngeal gonorrhea. At last, the answer

to the challenges of the post-antibiotic era! And time to bring back this classic ad campaign (see poster), with slight modification: “He’s not going to call — but the Department of Public Health will!” - Two-drug HIV therapy with dolutegravir and rilpivirine is non-inferior to continued triple therapy. Full results of these studies — called SWORD — are to be presented at a scientific conference, presumably at CROI in February 2017.

- IAS-USA released an update of the HIV drug resistance mutations. Even today, when emergent resistance to antiretrovirals is less common, this is a critical and authoritative resource for all HIV providers.

- The investigational HCV treatment glecaprevir/pibrentasvir has been submitted to the FDA. This protease inhibitor/NS5A inhibitor combination pill is a pan-genotypic approach that will be 8 weeks for treatment-naïve, 12 weeks for treatment-experienced or anyone with compensated cirrhosis. Clinical trials have included a wide range of patients, including those with HIV, advanced renal disease (including ESRD), and people who have failed current HCV therapy — the last of these granting a Breakthrough Therapy Designation, meaning likely fast approval.

- Think that because antibiotics in food is bad PR, there has been a significant decline in the food industry’s use? Think again — according to the latest FDA reports, sale of antibiotics to farms increased by 1% in 2015 compared with the year before.

- Topical azithromycin does not prevent Lyme disease. Oh well. On the plus side, there is at least some active research on a new Lyme vaccine.

- Phage therapy seems to have helped cure this case of multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas. It’s just a case report, and not (yet) in a peer-reviewed publication, but it’s quite the story nonetheless — and has prompted numerous non-ID doctors to ask me about it, especially in the ICUs. Fascinating list of potential non-antibiotics approaches to drug-resistant bacteria here.

- Results of anaerobic cultures rarely influence clinical management. In general, most of the patients with positive anaerobic cultures were already receiving therapy directed against the isolated bacteria, or there was no acknowledgement of the result at all. The authors call for anaerobic cultures to be ordered more selectively, which makes sense.

- Pubic hair grooming is associated with increased risk of certain sexually transmitted infections. In a study like this, the possibility of “confounding by indication” is astoundingly high (to be a stats nerd for a moment) — meaning that those who were extensively grooming may have been extensively doing other things, too! It remains a provocative finding nonetheless.

- If you’re cared for by a female physician, you’re more likely to survive. Maybe because so many of them choose ID and pediatrics!

Finally, it’s been a tough year for giants in music, especially if you’re a fan of a certain age. We lost Prince, David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, Leon Russell, Keith Emerson, Sir George Martin … and today, George Michael.

Here’s a somewhat less-famous song of his (certainly less flashy — here if you want that), with a nice late-Beatles/John Lennon quality to it, and lyrics quite appropriate to the times. Enjoy.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=goroyZbVdlo]

December 18th, 2016

Holiday Distractions, Dirty Pets, and Time to Vote for Your Favorite Cartoon Caption

Many people find it tough to concentrate at work this time of year. So much to juggle:

Many people find it tough to concentrate at work this time of year. So much to juggle:

- Holiday parties.

- Shopping.

- Travel plans — specifically, should we go with DEET or picaridin?

- Lots of high-carb, high-calorie foods stealing blood from our brains. Maybe too much eggnog or punch doing the same thing.

- Kids on vacation, with their demands for sustenance, adult supervision, and entertainment.

- Many critical work support people already away, with out-of-office messages implying that they’re not reading their email (but you know that they are).

Even our pets are distracted. After a crazy weekend of New England weather, starting with bitter cold, then a day of wet snow, and now a Spring-like thaw, Boston dogs and cats who ventured outside today are in bad need of bath.

(And yes, that was just an excuse to show off that magnificent picture of Louie. Click on it for full effect, I dare you.)

Plus, you have the distraction of our latest ID Cartoon Caption Contest, which generated so many outstanding entries that our powerful advanced humor algorithm was unable to limit the finalists to just three candidates this time. Even after we tweaked the settings, the powerful supercomputer churning through the entries kept overheating. We almost had to cancel today’s post and substitute a lengthy rumination on whether you should say Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) or Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI).

(Short answer: the former.)

So here’s the cartoon, plus the top four choices. Vote now before 2016 is no more!

(Drawing by Anne Sax.)

December 11th, 2016

You Want Guidelines? We Got Guidelines!

About a million years ago — in other words, probably sometime during my ID fellowship — I asked transplant ID guru Bob Rubin how various ID guidelines came together, including one on antifungal therapy he had just led.

“You lock a bunch of experts in a hotel conference room,” he said. “Provide them plenty of food and coffee. Then you hide the key until they come up with something, especially if there’s a deadline .”

Having participated on a couple of guidelines committees, I can attest that the process has changed just a bit since Bob provided me that memorable story. Conference calls, web-based presentations, and numerous shared documents with extensive “track changes” peppered throughout now dominate the process, along with frequent reminders about grading both the strength of the recommendations and the quality of evidence.

And, since we’re ID doctors, we of course try to outdo each other in obsessive attention to detail — emphasis on obsessive. While everyone makes a big noise about editing and shortening the final document, if that means eliminating one key reference, tell that to its champion — especially if they authored or co-authored the paper. It’s going in!

On the topic of guidelines, you might have noticed that the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has been on quite a roll over the past year. They’ve been churning out new guidelines at a blistering pace, often in collaboration with other medical societies. So here’s a look back on IDSA’s hard work over the past 12 months, each one highlighted with at least one notable and/or interesting recommendation, and also (just for bragging rights) the number of references (all thoroughly read, no doubt):

- Candidiasis. Last updated in 2009, these revised guidelines cover diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. A selected key recommendation: An echinocandin is recommended as initial therapy, with transition to fluconazole if the isolate is susceptible. Number of references: 560 — impressive!

- Antibiotic Stewardship. The first of its kind! A selected key recommendation: Rapid viral testing for respiratory pathogens is recommended to reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotics. Number of references: 225 — you have to think this will grow in the next iteration.

- Aspergillosis. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of this difficult-to-treat opportunistic infection. A selected key recommendation: Serum and bronchoalveolar lavage galactomannan can accurately diagnose invasive aspergillosis in high risk patients; the panel disagreed about using PCR. Number of references: 655! Wow, that might be hard to beat.

- Hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Retires the term “health-care associated pneumonia”, often abbreviated (and spoken) as “H-CAP” — will be hard for many to break that habit. A selected key recommendation: Duration of therapy should be 7-days (follows the rules!), not 8-15. Number of references: 364. Middle of the pack.

- Coccidioidomycosis. What a mouthful that fungal disease is, which must be why most people just say “cocci.” A selected key recommendation (actually two this time): No antifungal treatment for an asymptomatic pulmonary nodule (not even a bit of fluconazole?), while duration of azole therapy for coccidioides meningitis is lifelong. Number of references: 219 — a relatively “low” number, maybe because cocci’s geographic distribution isn’t very wide. Nah, 219 references is still a lot.

- Treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis. The winner for the most number of organizations involved in developing and endorsing these guidelines — I counted 9 (just read the start of the abstract). A selected key recommendation: Initial adjunctive corticosteroid therapy should not be routinely used in patients with tuberculous pericarditis. Number of references: 531 — would be top of the pack if you added the other TB Guidelines (which are next).

- Diagnosis of tuberculosis. First update on this topic in 17 years, so long overdue. A selected key recommendation: Use an interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) to assess for latent TB in place of the tuberculin skin test (TST) in most clinical settings. I’m ok with that! Number of references: 241 — hey, it’s just diagnosis after all.

- Leishmaniasis. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral disease. A selected key recommendation: Use a reference laboratory to perform culture and PCR in an effort to identify the infecting parasite to the species level, which may have implications for management. Number of references: 503, which exceeds the number of cases of leishmaniasis I have seen by 498.

That’s 8 Guidelines, and a total of 3,298 references. Hard at work, IDSA!

Of course no listing of IDSA Guidelines these days is complete without the invaluable HCV guidelines, which I’ve praised (and use) often. They’ve changed so frequently since their inception that they have their own special site, and aren’t really “published” anywhere else — at least not in a traditional medical journal. On the plus side, this allows the HCV Guidelines greater flexibility, with modifications on an as-needed basis (three times in 2016 alone) for important changes in the field — a nod to the DHHS HIV Guidelines, which have a similar structure. On the minus side, there’s no real peer review, and I’m sure some of the writers of the guidelines (especially those seeking academic promotion) wouldn’t mind a byline discoverable in PubMed.

And they don’t number their references, so someone else has to count. Kind of like guessing the number of pennies in a big jar to win a prize.

Finally, here are some bears playing with a pink balloon. Just because.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzNEna-PETY]

December 4th, 2016

Just Wondering: Quick ID/HIV Questions to Ponder During Month Number 12

A selection of ID/HIV questions that have been dogging me over the past year, some longer:

- Why is there no reliable, readily available PCR diagnostic test for malaria? Seems especially ironic since the one for babesia has become so commonly used. Does the Binax antigen test make it unnecessary?

- Why aren’t we actively recommending Zika testing for couples who return from endemic areas and are interested in conceiving? A negative test would make a low-likelihood but serious outcome (congenital Zika) even less likely. They could still wait the recommended six months if they want.

- What is the right abbreviation for Pneumocystis pneumonia? Is it “PCP” (PneumoCystis pneumonia) or “PJP” (Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia)? Have heard smart people use both; I prefer the former.

- Once there are more manufacturers of generic daptomycin and the price drops, how long before it’s used more than vancomycin? If we never have to monitor vancomycin levels again, there should be a small celebration.

- In the big new HIV vaccine study just starting, how many participants will also be receiving PrEP? Here’s the study design of HVTN 702, and PrEP clearly is allowed. I suspect it won’t be available to most of the participants, otherwise it could make it hard to discern whether the vaccine actually works.

- Does anyone really know the full meningococcal vaccination recommendations without looking them up? For the 99% of us who don’t, here they are. This is an old bugaboo, inspired by the new recommendation to give meningococcal immunization to all HIV patients.

- Could the headlines be any more misleading about how many patients contracted HIV or HCV from the dentist who used his own equipment? Here’s an example — you have to read it carefully to make sure you see the “May” in there. But gotta sell papers/get clicks (and I just contributed to the latter).

Speaking of, is this the headline of the year? I think we have a winner, folks — “GOVERNMENT DRONES WILL SHOOT VACCINATED M&MS AT PRAIRIE DOGS.” The disease, for the record, is the “sylvatic plague.” You have to read the full story to believe it. And just wait for the anti-vaxxers to protest.

Speaking of, is this the headline of the year? I think we have a winner, folks — “GOVERNMENT DRONES WILL SHOOT VACCINATED M&MS AT PRAIRIE DOGS.” The disease, for the record, is the “sylvatic plague.” You have to read the full story to believe it. And just wait for the anti-vaxxers to protest.- If primary care clinicians had a rapid diagnostic test that could tell patients definitively that they had a specific viral respiratory tract infection, would this decrease the use of outpatient antibiotics? They could say, “Mr. Smith, your test came back, and you have rhinovirus.” I say “Yes it will”; my colleague Jeff Linder (a primary care internist who studies antibiotic overuse) is skeptical.

- Will broadly neutralizing antibodies (“bNAbs”) ever have a role in HIV treatment? Not based on this study. Admittedly it’s early in bNAb research, but to date I’m not getting the bNAb enthusiasm.

- We have penicillin G, and penicillin V, but what about the other letters? Hat tip to John Cafardi for this one.

- Wouldn’t it be useful if ID doctors had some formal training in wound management? Big gap for many (most?) of us.

- What percentage of non-occupational HIV post-exposure prophylaxis courses are unnecessary? I’m estimating 99.9994%, but that train seems to have left the station, with no going back.

Why did the new makers of crofelemer change the name from (the absurdly wonderful) Fulyzaq to (the less remarkable) Mytesi? And here’s an artist’s rendition of a Mytesi, in case you were sad about the extinction of Fulyzaq.

Why did the new makers of crofelemer change the name from (the absurdly wonderful) Fulyzaq to (the less remarkable) Mytesi? And here’s an artist’s rendition of a Mytesi, in case you were sad about the extinction of Fulyzaq.- In Lyme-endemic areas, why is there no recommendation to give a single dose of antibiotics to children with tick bites? Odd that we use this strategy in essentially all adults, and almost no children — it’s as if we were applying drinking-age criteria to this completely unrelated issue.

- Why is a CSF exam recommended in all patients with optic or otic syphilis? Treatment is the same (IV penicillin) regardless of the results. Have been asking this question for years.

- What fraction of HIV viral load tests that come back “VIRAL RNA DETECTED BUT BELOW THE QUANTIFIABLE RANGE OF THE ASSAY” are clinically important? Boy that must be rare. The ratio of (Emotionally important to patient)/(Clinically important to patient) must be nearly infinite.

- What’s it like to have an oral carbapenem? Someone from Japan might know.

Ok, time for a couple of quick non-ID ones:

- When will the Washington Redskins change their offensive name? Or the Cleveland Indians get rid of their unfunny mascot?

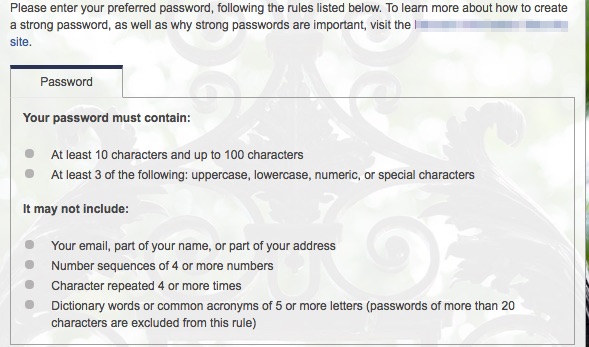

- When will the torture of choosing a password be replaced by something easier and more reliable? Here’s one recent example. Arrghh.

Hey, it’s National Influenza Vaccination Week! Check your party schedule carefully.

November 25th, 2016

ID Cartoon Caption Contest #2 Winner — and a New Contest for the Holidays

Every so often, one of my regular readers (which must number at least a dozen at this point, including my extended family, dog, and cat) asks me where I come up with ideas.

The answer, of course, is that there are infinite sources of inspiration in the field of Infectious Diseases — the difficulty is choosing what fascinating topic will be the target of this week’s cogent and definitive analysis.

Or, I can just steal something, which is what I’ve unabashedly done with the Cartoon Contest, modeled after the more established version from The New Yorker.

And here’s the winner of the summertime contest, an outdoor scene that might bring back fond memories of warm breezes, long days at the beach, and dining al fresco:

We’ll give Philip Morganelli the top prize on this one, though he’ll need to share the generous honorarium with John Lee, who introduced the whole “carbon footprint” theme and might have provided Philip some inspiration.

But I confess this contest turned out a bit differently than anticipated. With such an ID-oriented crowd, I figured the obviously very well-done burgers would generate plenty of funny captions about food safety. If you’re wondering what I mean, take a look at this most unappetizing food truck:

Concern about underdone burgers prompted my next door neighbors Ben and Carol to call the well-done hockey pucks favored by ID specialists “Madoff burgers”. It’s in honor of Dr. Lawrence Madoff, an ID doctor who works at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, who periodically attends our neighborhood cookouts — you can guess Larry’s emphatic answer to the question, “And how would you like that done?” Perhaps he will be introducing his own line of crispy fast food soon.

Yet none of the top three captions chosen by our AHA (Advanced Humor Algorithm) had anything remotely to do with infectious food safety:

- “No thanks, I’m watching my carbon footprint.” (the now-famous Philip Morganelli)

- “Sorry, I was using fire in the belly as a figure of speech.” (JRMD)

- “No thanks. They always give me heartburn.” (Aaron Kassoff)

Perhaps I poisoned (ha) the ID entries by introducing the drawing with this gloomy sentence: “We must be vigilant to the ever rising threat of both foodborne pathogens and carcinogenic heterocyclic amines.” Come to think of it, that alone could have been a (very unfunny) caption.

This time, you’ll get no such leading leading statement — here’s the cartoon, let your inspiration run wild:

Post captions in the comments section (preferred), or if you’re shy, email them to me at id.caption@yahoo.com.

(Drawing by Anne Sax.)

November 20th, 2016

Seven ID/HIV Things to Be Grateful For This Holiday Season, 2016 Edition

I know, I know — you read that title and thought, “Grateful now? He must be out of his mind.”

I know, I know — you read that title and thought, “Grateful now? He must be out of his mind.”

But with the (unsurprising) concession that I too felt that watching the election returns was akin to witnessing a slowly developing and incomprehensible train wreck, I remind you that the expression of gratitude is well known to make you happier. Plus, it’s the season.

So here’s a brief list of things in our fascinating field to be grateful for as you get the turkey ready. As a bonus, I’ve put a few non-ID ones at the end, because, well, why not?

- New diagnoses of HIV in the USA are down — really! After decades of HIV incidence being stubbornly stuck at the same level since the early 1990s, new diagnoses have declined 19% since 2005. Yes, 40,000 new diagnoses/year is clearly too many, and new infections are still too common in black men who have sex with men — but they are down in all other groups. Chalk this significant decline up to several important factors: 1) more testing; 2) more people on treatment; 3) more people on treatment that actually works; 4) more of those at-risk but negative on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Ever the optimist, I predict further declines in HIV diagnoses in the years to come.

- Hospitals are mandated to have antibiotic stewardship programs coordinated with infection prevention efforts. Or, to put it more accurately, they must have these programs if they want to get paid by Medicare and Medicaid, which is quite the incentive. If that’s not enough, The Joint Commission, which accredits and certifies US hospitals, agrees. ID doctors have been warning about the risks of antibiotic resistance for years; these rulings really put some momentum behind antibiotic stewardship and infection control efforts, a tremendous opportunity to improve patient care — and for ID in particular to take a leadership role in making this happen.

- Access to hepatitis C therapy has vastly improved, and the remaining treatment challenges have been solved. I acknowledge that access isn’t the same in all states, but here most payers — including even Massachusetts Medicaid — have abandoned “fibrosis requirements” for HCV therapy, which were never defensible medically anyway. In fact, we can get approval for treatment for almost everyone, regardless of payer, because the costs of treatment are way down from the “sticker price” — enough so that HCV treatment is now considered “High Health System Value” by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a group initially quite critical of HCV treatment pricing. And with the approval of velpatasvir/sofosbuvir and elbasvir/grazoprevir, two of the remaining challenges in HCV therapy — genotype 3 and patients with renal disease, respectively — are now checked off. Two ongoing issues are diagnosing patients before they have significant liver disease (a large proportion of those with HCV don’t know they have it), and the rare cases of treatment failure with resistance. Good news here, too — early diagnosis should improve with better therapy (see HIV example above), and the patients with treatment failure will have new options soon. You are hereby forgiven if you don’t know (yet) what voxilaprevir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir are, though you will need to know soon.

- MRSA rates continue to decline. If you asked me in the mid-2000s to forecast the status of Staph aureus susceptibilities, I would have predicted that the MRSA USA300 strain was going to take over the world, laying waste to susceptible strains and causing painful abscesses, kind of like Godzilla stomping through downtown Tokyo. (What a terrible analogy. Sorry.) It was so bad I wrote this desperate post about MRSA almost 10 years ago. Fortunately, I was WRONG (not the fir

st or the last time). While still common, MRSA has declined both in the hospital and the community settings. Not only that, but penicillin-sensitive strains seem to be making a comeback, somehow re-emerging from the pre-penicillin 1930s decade like a Lincoln Zephyr Coupe. Is that analogy better?

st or the last time). While still common, MRSA has declined both in the hospital and the community settings. Not only that, but penicillin-sensitive strains seem to be making a comeback, somehow re-emerging from the pre-penicillin 1930s decade like a Lincoln Zephyr Coupe. Is that analogy better? - The University of Liverpool HIV and hepatitis drug interactions resources are better than ever, and invaluable. When most people think of Liverpool, their first association is probably The Beatles, and second football (you know, what the rest of the planet calls soccer). ID doctors, however, might think of something else — the University of Liverpool gives us the very best resources for HIV and hepatitis drug interactions, and if you aren’t using them yet, start now — they will make your prescribing life so much easier. Note that the excellent web site and mobile apps have recently been redesigned, making them better than ever.

- Applications to ID fellowships are up. The final numbers aren’t in, but it does appear that a discouraging downward trend has, at least for this year, been reversed. Too soon to say if this will continue, but I can also say anecdotally that the applicants we had this year were excellent — smart, engaging, curious, interested in a wide variety of ID topics, and just the sort of people we want for the field.

- John Bartlett’s annual “What’s Hot in ID” lectures at IDSA/IDWeek. John’s can’t-miss lectures follow a logical game plan: he chooses the top 5-8 issues in Infectious Diseases over the past year, highlights the key studies, synthesizes the take-home messages, and — here’s the best part — he then says, “So I called [first-author of the paper] about this surprising result, and this is what he [or she] told me.” Pure gold — educational, entertaining, just fun — and this year’s talk was no exception, so I’m sad to report that he’s told me that this will be his last lecture at IDWeek. I’ve written about John before — thank you for teaching us so much!

Plenty of other topics I could have included, but here are a few non-ID items I’m also grateful for, just for fun:

- Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me! The best (and funniest) way to get the news, especially since John Stewart left The Daily Show.

- The Cubs won the World Series. It had been a while (you might have heard that).

- An electric car is the Motor Trend Car of the Year, and it’s not even a Tesla. Surprise, it’s the Chevy Bolt, and Motor Trend says it can hear “the sound of the automotive world shifting on its axis”. I barely drive, but can only imagine how much better our planet would be without every car having an internal combustion engine.

- Television has never been better. An indisputable fact.

- Simone Biles and Usain Bolt. Amazing X 2.

- Bill Bryson’s books. All of them.

- Spiralized vegetables. Where did these come from?

- The Poscast. In which Joe Posnanski (my favorite sports writer) and comedy writer Michael Schur have long, pointless, and incredibly funny discussions.

- Asturias, by Isaac Albeniz. On the guitar, of course.

- Bailey, a lost dog in Brooklyn, was found. Just read the story.

What are you grateful for this year?