An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

March 16th, 2023

Oral Antibiotic Therapy for Endocarditis — Are We There Yet?

Two terms in clinical research appear frequently in abstracts, conference presentations, and published papers — “clinical practice” and more recently, “real-world.”

Many research snobs turn up their noses at both, finding them imprecise or pretentious. I confess to flinching each time I read “real-world” — isn’t everything “real-world”? If not, what’s the opposite? Mouse studies? (They’re certainly the real world from the mouse’s perspective, though not in a way that they would like.) Work done “in silico”? Trial participants recruited from the film Avatar?

But having collaborated in several real world studies over the years, I realize there is a reason to signal that data come from actual clinical practice — that is, derived from people in care, outside the specified and restricted domains of a prospective research protocol.

One such paper just appeared in Clinical Infectious Diseases, entitled “Real-world Application of Oral Therapy for Infective Endocarditis: A Multicenter Retrospective, Cohort Study”.

Here I’d argue that this “real-world” description is highly appropriate — because, as the authors note, despite evidence from randomized clinical trials on the efficacy and safety of oral therapy to complete treatment for endocarditis, uptake of this practice remains highly limited. We need people to report what they’ve seen after implementing this novel strategy.

The authors cite experience within their healthcare system in 46 patients treated with oral therapy, compared with 211 who received IV. Importantly, these cases occurred after their system implemented an “Expected Practice” document sanctioning oral therapy in stable patients with no contraindications.

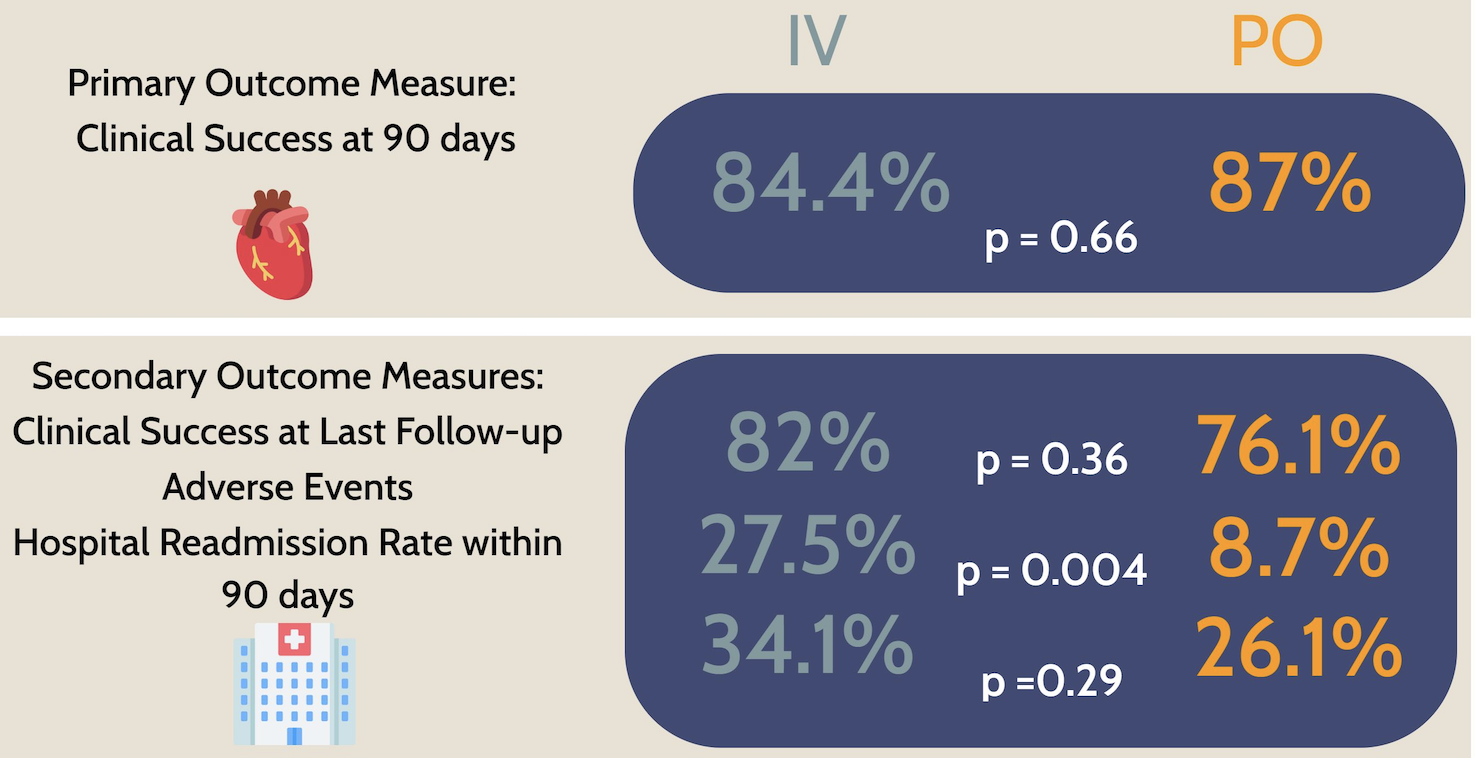

Here are the results:

Looks great! As no fan of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT), I was delighted to see that adverse events occurred significantly less often in the oral treatment group.

Skeptics will argue that the biggest limitation of these data is that, like all nonrandomized studies, baseline differences between the two groups could have influenced the outcomes independent of the type of treatments they received. Specifically, the IV-only group was older with more comorbidities, while the oral antibiotic group had a higher proportion with a history of injection drug use. A multivariable regression analysis factoring in these differences did not demonstrate a significant impact on outcomes, but unmeasured differences cannot be accounted for.

Limitations notwithstanding, the study provides helpful reassurance about the practice of using oral therapy to complete treatment for endocarditis — a practice that would have been unimaginable a decade ago.

Curious to hear from readers, especially ID docs, pharmacists, and other clinicians doing hospital-based medicine — are you using oral therapy for endocarditis?

If so, in what settings?

Hello!, very nice information. It is always great to read this blog!

I am an ID doctor, and at my place of work we dont use oral antibiotics for IE. Our reality is complex. I m from Argentina.

I know that in Barcelona, Spain, dr Miró and his team, use oral treatment for very carefully chosen patients.

Thank you for this update, Paul. It’s very timely, as I just lectured on IE a few days ago (and quoted you regarding the general public’s lack of appreciation of the dangers of invasive bacterial infections like IE, compared to HCV and HIV). I don’t do hospital-based medicine, so I can’t comment on that. But I was glad to see this new study included patients with MRSA infections (nearly 35% in the oral abx cohort). As I recall, the POET trial did not include anyone with MRSA. The new study’s inclusion of more people with a history of IV drug use is also appreciated.

It would be great if completing treatment with oral therapy could be incorporated into treatment guidelines. Any idea when this might be coming?

I think the biggest impediment to adopting this approach is medico-legal.

We know that endocarditis treatment will fail in some cases even with standard IV ABX, but if we use oral antibiotics and there is a poor outcome, could that potentially result in a lawsuit or disciplinary action because we have deviated from standard practice?

Having an “Expected Practice” document is a nice way to relieve some of that pressure. Hopefully studies like this one will help us become more comfortable with treating endocarditis with oral ABX.

After OVIVA and POET were published, I asked a hospital attorney his thoughts on transitioning to oral antibiotics for these infections (in the context of an ethics meeting regarding an injection drug user with myriad presentations with MRSA bacteremia and equally many AMA discharges). His response: “If it is standard practice of other physicians in the area, it would be defensible.”

This has made me reluctant to use orals, particularly for endocarditis given guidelines as Daniel mentions above. I have on several occasions for bone/joint infection, but only after documenting more-or-less informed consent that OPAT may be seen as standard-of-care yet more and more data support orals as noninferior and safer.

These medico-legal issues are very much on my mind, even as we move forward with a change that makes sense medically. If you add to this the common public perception that IV therapy is “stronger”, it’s particularly fraught with risk.

On the plus side, most people truly hate being on home IV therapy. They (and I) are joyful when the PICC line comes out and the OPAT stops.

Seems like an ideal setting for shared decision making — as is often the case!

Paul

I think you are exactly right here. It’s imperfectly analogous to antibiotics instead of surgery for acute appendicitis. Some have strong feelings about having the surgery and being done. Others happily opt for antibiotics even if there is up to a 30% chance of recurrence.

It’s the most satisfying part of medicine to have limited advanced data and to offer patients (and families when appropriate and desired) a role in making these types of decisions.

Thanks Paul for this (as always) very inspiring contribution. I fully agree to your comment on “real world data”, and I would even go a step further: we should not use it at all. The term obscures the scientific imprecision, that ist frequently inherent in these studies. And – as you elucidate – it suggests, that data of formally conducted studies may be “not real”. In my view, this is a wrong and dangerous framing. We have already terms for these studies: observational studies or cohort studies set another tone, have a very sound scientific background, and should be used instead of “real world data”. As ID physicians, we should always aim for an exact and very specific language. Maybe Clinical Infections Diseases can restrain from this term in the future?

When guidelines for oral therapies are developed by IDSA or others, it will be important to exclude from panels those ID docs running OPAT programs as they have a financial conflict of interest.