An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

March 2nd, 2024

Just as CROI Gets Ready to Start, an Important Change to the IAS-USA HIV Treatment Guidelines

One of the top experiences of my ID career has been working with a research group that does HIV disease modeling. The people involved are without exception smart, collaborative, generous, funny, and hard-working — an amazing combination of positive traits.

One of the top experiences of my ID career has been working with a research group that does HIV disease modeling. The people involved are without exception smart, collaborative, generous, funny, and hard-working — an amazing combination of positive traits.

They get this, I believe, from their leader and founder, Dr. Ken Freedberg, who sets a great example. He has been a research mentor and friend of mine for years.

(You might recognize one of his many mentees: Hi, Rochelle Walensky, if you’re reading this!)

Anyway, it’s not often that I disagree with Ken on anything in the HIV treatment area, so it’s been an interesting couple of years as we discussed a strategy that’s been on the cutting edge as a way to manage some of our most challenging cases — namely, the people with HIV who (for a variety of reasons) do not take oral antiretroviral therapy.

As anyone who does HIV care knows, this small fraction of our patient population occupy a disproportionate share of our worries, account for the bulk of hospitalizations and HIV-related deaths, and as a result represent an ironic (and tragic) contrast to the extraordinary success of HIV treatment. It’s unfathomably frustrating on many levels.

The reasons they do not take ART are numerous, and not mutually exclusive — including denial, stigma, mental illness, and substance use disorder — but a glimmer of hope emerged with successful reports of the off-label use of injectable cabotegravir-rilpivirine (CAB-RPV) in a group of people with ongoing viremia who are not taking ART. While these reports first appeared from Ward 86 in San Francisco under the direction of Dr. Monica Gandhi, other studies and anecdotal evidence from clinical treatment sites (including our own) followed.

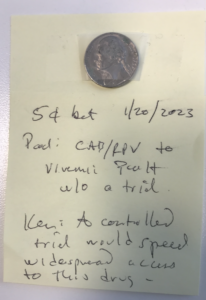

But back when these reports first emerged, Ken took the position that widespread use of this treatment would require a prospective clinical trial, preferably with a randomization to standard of care, to prove that it works; he furthermore thought that it would not appear in guidelines until such a study took place. I countered that such patients have already proven that they will experience treatment failure if randomized to continue oral therapy, and that such a study would not be necessary to show that injectable ART is the best strategy under these desperate situations.

We bet a nickel. Evidence in photo at the top of this post.

Ken may have gotten his wish. The injectable strategy for people who struggle with adherence got a boost with the announcement of results from the LATITUDE trial, an ACTG study that enrolled people with treatment failure. It provided economic incentives to lower the viral load to undetectable with oral ART, and then randomized them to injectable versus continued oral therapy. The study was stopped early in favor of the injectable ART arm; we’ll see the full results at CROI next week as a late-breaker.

It’s not quite the same population as the one we’ve been discussing (the randomized switch to CAB-RPV in LATITUDE is only after virologic suppression), but it’s close.

Meanwhile, I’ve been energetically pitching to my colleagues on the IAS-USA Guidelines Panel to update our recommendations for use of cabotegravir-rilpivirine for people not able to take oral ART who have advanced HIV disease. The argument is simple: such an intervention can be literally life-saving given the poor prognosis of untreated HIV with low CD4 cell counts, or prior HIV-related complications. Takes us back to the bad old days, pre-1996.

I’m thrilled to report that this revision just appeared in JAMA. Note that this intervention is not for all people who struggle with adherence — just those at the highest risk for HIV disease progression:

When supported by intensive follow-up and case management services, injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine (CAB- RPV) may be considered for people with viremia who meet the criteria below when no other treatment options are effective due to a patient’s persistent inability to take oral ART:

– Unable to take oral ART consistently despite extensive efforts and clinical support

– High risk of HIV disease progression (CD4 cell count <200/μL or history of AIDS-defining complications)

– Virus susceptible to both CAB and RPV

It will be critical to assess how this treatment does in clinical practice, to monitor for emergent integrase and NNRTI resistance, and to provide the intensive case management services this patient population deserves. And if a prospective study starts employing this strategy, one that does not involve a randomization to continued oral ART, all the better to gather more data on how it performs. Enrollment highly encouraged.

But as we’ve demonstrated in a modeling study, injectable CAB-RPV doesn’t need to be 100% effective in a population with advanced HIV disease to save lives — even a virologic suppression rate of 45% would do the trick.

Did I win the bet? Or did Ken? I say we both save our nickels, and call it a tie.

This revision is great news! Agree with you that an RCT is not needed. Rather, it would be so helpful if those of us in smaller, non-research oriented sites who are utilizing this off-label protocol in small numbers could collaborate and report out in aggregate. Perhaps BWH wants to support and coordinate this effort :)??

Concern for/research re: potential development of resistance due to incomplete suppression, which would also impact its effectiveness for PrEP?