An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 9th, 2019

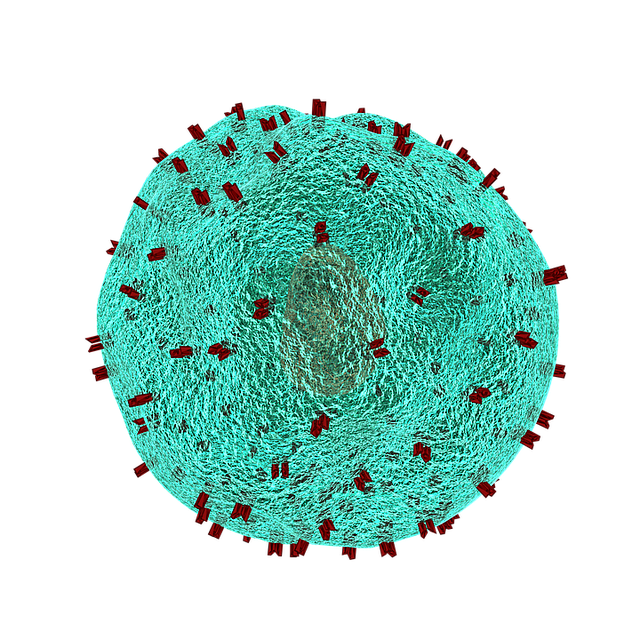

Is It Safe to Alter the CCR5 Receptor? And How Will This Influence HIV Cure Studies?

The HIV cure effort suffered a potential setback this week, as researchers reported an association between having two copies of the CCR5-∆32 mutation and shorter survival.

The HIV cure effort suffered a potential setback this week, as researchers reported an association between having two copies of the CCR5-∆32 mutation and shorter survival.

(Quick reminder — the CCR5 receptor is required for most HIV strains to enter target cells. People homozygous for the CCR5-∆32 mutation are almost completely protected from contracting HIV.)

By evaluating over 400,000 individuals in a British registry that included genetic information including CCR5 status, the investigators compared the prevalence of CCR5-∆32 homozygosity among people between the ages of 41 and 76. Over time, the prevalence substantially declined, consistent with a 21% increase in all-cause mortality compared to those with either no ∆32 mutation, or heterozygotes.

The authors postulate that this excess mortality may be driven by the reported worse outcomes among those with ∆32 homozygosity who develop influenza or other infectious diseases. Since most influenza deaths occur in older people, this could explain why earlier studies of populations with ∆32 reported them to be healthy.

(By contrast, it might be that historical epidemic infections of childhood and young adults — smallpox, plague, dysentery among them — could have selected for ∆32 many centuries ago, with the result that approximately 10% of people of European heritage carry at least one mutation.)

As noted in the excellent editorial accompanying the new study, the findings should give researchers pause before making permanent changes to the host genome:

The most important point raised by the current publication is that considerable risk comes with generating mutations in the genome of human beings, no matter how obvious the benefit that those mutations offer.

I’d amplify this concern by noting that individuals born with two CCR5-∆32 mutations — who grow up with it — may differ from those in whom CCR5 is altered during adulthood. We simply don’t know whether people who acquire it late in life will be better or worse off than those born with the mutation.

So why is this recent study relevant to curing HIV? Considerable research has already been done on this receptor related to HIV cure:

- Only two people — the “Berlin” and the “London” patients — appear to have been cured of HIV. Both underwent stem cell (bone marrow) transplantation using donor cells harvested from people homozygous for the CCR5-∆32 mutation. The indications for the transplants were refractory leukemia and lymphoma for the Berlin and London patients, respectively. Both are off antiretroviral therapy with no viral rebound, and no virus detected either in blood or tissues.

- Zinc-finger nucleases successfully excised the CCR5 receptor from some cells of people with HIV. This small study (n=12) was a first step in trying to engineer something analogous to the Berlin and London patients without the risk of stem cell transplantation.

- A scientist reported that he used CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing to disable the CCR5 gene of two babies. The announcement was hugely controversial, as there was zero medical justification for this experiment on these children born to an HIV-negative mother. However, the cases underscore the feasibility of altering a person’s genome using the powerful tools available today.

- There is substantial ongoing research in coreceptor modification to prevent or cure HIV. In the linked review, it states “there are multiple clinical trials underway to evaluate how efficacious this therapy can be in human patients.”

Clinicians not actively caring for people with HIV might wonder whether the risks are worth it — isn’t HIV therapy now safe and all but 100% effective?

The reality is that there’s tremendous interest in HIV cure, especially among those with HIV, risks notwithstanding.

So great is this interest that many of us have even been asked by our patients whether they can have a bone marrow transplant:

Poll for people caring for those with HIV: Have you had a person with stable HIV ask if they could have a bone marrow transplant so that they can be cured, like the "Berlin Patient"? Thoughts about this? https://t.co/5ELxB6FFR7

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 8, 2019

That these questions mostly come from people doing quite well on their HIV therapy signals a powerful patient-driven motivation for HIV cure — one that sadly seems more related to ongoing HIV stigma than to the medical issues of current HIV treatment.

Which is why it’s not so clear that this latest research finding should dampen the pursuit of CCR5-driven cure strategies.

Would a lifetime 21% increase in all-cause mortality be an acceptable trade-off for a person with HIV who is deeply invested in HIV cure?

And who will get to decide?

I can guess that if we had cure for HIV, about 50% of my cured HIV would get infected again in short time.

Seems to me a futile research.

So, cure them, and put them on PrEP. Boom.

Then again, if they’re cured by some kind of gene therapy to CCR5, they may become uninfectable.

Regardless, even if only half of our patients aren’t reinfected (which is pretty pessimistic), that’s worth the effort IMHO.

Thanks for this, Paul. Indeed, there is considerable interest in HIV eradication and/or SVR in the PLWH community. One question: how might this impact patients currently taking maraviroc? It seems to me that there would be a difference between blocking CCR5 and having undergone modification to eliminate CCR5 expression. Thoughts?

David,

Excellent question! One of the longstanding concerns with maraviroc has been that it’s the only antiviral with a focused cellular (rather than viral) target, which could have some immunomodulatory effects (some good, some not good). But I agree that a blocker of CCR5 might fundamentally different from something that alters CCR5 expression, or “snips” it off. All could be different in ways from those who are born without that receptor due to delta 32 mutation.

Lots to think about!

Paul