An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 7th, 2020

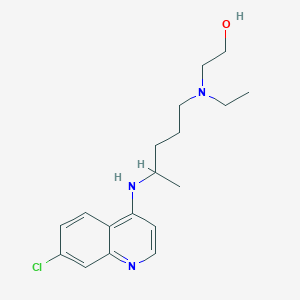

Hydroxychloroquine Not Effective in Preventing COVID-19 — In Praise of a Negative Clinical Trial

The headlines might read, Malaria Drug Ineffective in Preventing COVID-19 — but that doesn’t do justice to a remarkable clinical trial, just published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Led by Dr. David Boulware at the University of Minnesota, the study asked this question: Does hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) prevent the development of COVID-19 in people after significant healthcare or household exposure to the disease?

To say that the recruitment of this post-exposure prophylaxis trial was innovative hardly gives the methods enough credit. I first heard about the study in mid-March, based on this post by the lead author:

Healthcare worker exposed to COVID-19? Sharing a home with someone with COVID-19? Our Univ. of Minnesota team at the has launched a clinical trial studying a drug that may help prevent infection in those exposed to coronavirus. Email us at covid19@umn.edu to enroll.#IDTwitter pic.twitter.com/eFa425j2Z5

— David Boulware, MD MPH (@boulware_dr) March 17, 2020

It wasn’t long after reading this that I received a frantic message from one of my long-term patients with just this sort of high-risk exposure. I immediately referred him to the study.

With this study design, he didn’t have to fly to Minnesota to enroll — it was all done remotely. Informed consent, medication dispensing and shipment, adverse event monitoring, endpoint assessments.

(He did fine, by the way.)

In essence, this randomized, placebo-controlled study gives new meaning to the phrase “multicenter clinical trial”! I count 821 “centers” — specifically, the homes of the 821 participants, 414 of whom received HCQ, 407 placebo.

As the authors note, the conduct of the study had major advantages:

This approach allowed for recruitment across North America, minimized the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection to researchers, lowered the burden of research participation, and provided a timely answer to this question of whether postexposure prophylaxis was effective. Moreover, this approach allowed broad geographic participation regardless of anyone’s physical distance from academic centers, increasing the generalizability of the findings.

Think also of the countless time, money, and effort saved by avoiding the need for local institutional review board approvals, clinical trials contracts, and study visits. Remarkable.

No, this isn’t the first study to enroll and follow participants remotely — the groundbreaking Physicians‘ and Nurses’ Health Studies come to mind. But it’s certainly the first one conducted and completed during a global pandemic.

For the record, the incidence of clinical COVID-19 illness did not differ significantly between groups (11.8% for HCQ, 14.3% placebo), and people receiving HCQ had more side effects, mostly gastrointestinal. There were no serious cardiac adverse events, a problem reported on other studies (especially when combined with azithromycin).

As noted in the accompanying editorial (and acknowledged by the authors), the study had several limitations, most notably the small proportion of COVID-19 cases (just over 10%) confirmed by PCR, and the delay (3 or more days) between exposure and starting preventive treatment. Furthermore, such a remotely conducted study cannot collect highly detailed data.

These and other limitations mean that these results may not be definitive; other prevention studies with HCQ continue.

Still, kudos to the investigators for so quickly carrying out this remarkable study. It’s a reminder that sometimes the innovation in clinical trials comes in the methods section, not in the results.

Smart and pragmatic, a potent combination. Thank you for pointing out the beauty of this study design.

I wonder if the assumed effect size was too high in the sample size calculation, which led to a non-significant reduction of 17.5%.

Was the study underpowered for its primary outcome?

I like the innovative idea, but I seriously question the value of a study with such devastating limitations.

No factual conclusions could be drawn. Perhaps this was an unintentional outcome of the design, but it should have been anticipated.

I believe the resources should have been better spent.

Young individuals – 40s

Hmm wonder if they had any in 80s

We need a trial where the HCQ was started before exposure to see whether HCQ can prevent the disease.

In many centers in India HCQ is given as a prophylaxis for health care workers exposed to COVID -19. The numbers who take it as a primary prophylaxis is not small. We have to address this population before we stop the true prophylactic treatment.

An interesting candid study but the results do not prove that HCQ is ineffective in prevention of novel Corona virus acquisition. The HCQ and placebo were administered AFTER the exposure, which limits the scope of study.

HCQ prevents malaria when the prophylactic regime is started WELL BEFORE THE EXPECTED EXPOSURE and is continued for weeks after leaving the endemic area. It has been proved to be extremely effective and is still advised to the travelers.

A study with similar protocol, starting HCQ couple of weeks BEFORE expected exposure to novel Corona virus and continuing for couple of weeks AFTER the last exposure to novel Corona virus would perhaps be more reliable. In addition, the severity of Covid 19 in those who get infection also needs to be studied and compared. Many a time, the prophylaxis drug regimen (like vaccines) does not prevent the acquisition of infection but can moderate the course of the disease.

The pandemic is still on and we have lost lots of health care workers. It is not too late to plan and start such a study. If it works for health care workers, it can be extended to other high risk groups as well.

Isn’t it about time we allow chloroquine to rest in peace as far as Covid-19 is concerned? One should just compare in vitro IC50 and plasma levels normally achieved with recommeded doses to realize that it never stood much of a chance to begin with