An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 12th, 2025

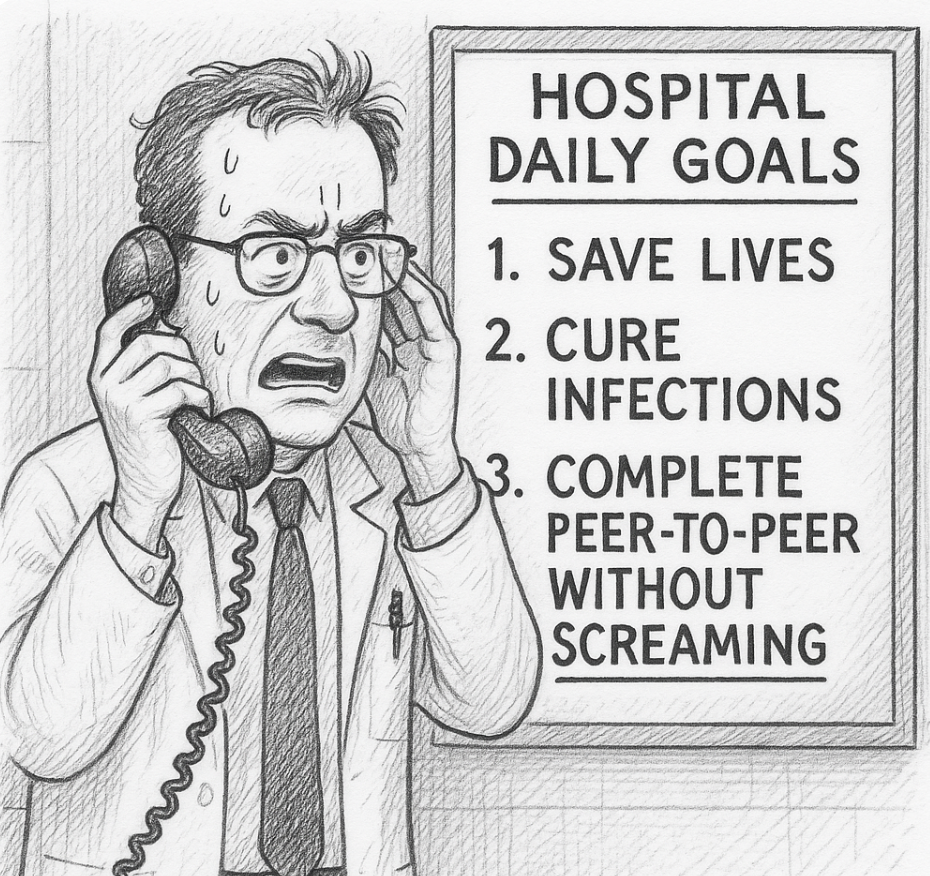

The Patient Did Well — So the Insurance Company Won’t Pay

Sometimes, you can predict a bad outcome. Examples:

Sometimes, you can predict a bad outcome. Examples:

- Proposing marriage after an awkward first date — and doing so over gas station nachos.

- Moving to a Cambridge apartment with no off-street parking, then buying a Tesla Cybertruck.

- Trying to recruit for ID fellowships from a group of cosmetic dermatologists.

But predicting what happens in clinical medicine? Not so easy. Which is why the clairvoyance expected by certain health insurance companies baffles the mind — they seem to believe we can diagnose, prognosticate, and determine outcomes with the omniscience of the Oracle of Delphi.

Take this recent gem. I’m sharing it here not because it’s unusual, but because the absurdity deserves a moment in the spotlight.

(Part of a series.)

Here’s the scenario (some details changed to protect privacy):

The patient, a 64-year-old man, went to our emergency room with fatigue, acute kidney injury, and a hemoglobin drop. He’d recently undergone gastric sleeve surgery, making the clinical status more uncertain than usual — plus a background of diabetes and high blood pressure as medical comorbidities. Given the symptoms and risk factors, he was admitted to medicine for hydration, monitoring, and endoscopy. He got better. We all celebrated. Cue the credits.

But then… the sequel. (Spoiler alert: It’s a horror film.)

A few days later, I received an email saying that the insurance company had denied inpatient level of care — in plain English, they didn’t want to pay. Would I have time to do a “peer-to-peer” discussion to try and reverse the decision?

They might as well have asked me to call an airline to rebook a cancelled flight during a massive Nor’easter, that’s how much I was looking forward to this task. But given how justified the admission was, and my trying to be a team player to defend good clinical practice in the face of our Private Insurance Overlords, I set up some time to talk with my “peer.”

I use quotation marks because while I’m sure she was, technically, a healthcare professional, her role in this drama felt more like prosecutor than peer.

She had some of the hospital data. Not all. Enough to cherry-pick to support their refusal to pay, but not enough to understand the full context of the case since, of course, she had never seen, spoken with, or evaluated the patient.

She asked me a series of questions, some of which were about information she already possessed, as if hoping I’d contradict myself like a suspect in a police procedural. (“So you’re saying the patient had a drop in his hemoglobin during the hospitalization? Interesting, doctor… very interesting. I see here it remained 7.5–8.3 during his stay. Do you consider that a drop?”)

I explained, again, the patient’s presentation. The drop in hemoglobin from his baseline of 10.5. The post-bariatric surgery. The concerning acute kidney injury in someone with diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. You know — the reasons why he was admitted.

But then came the decision, delivered with the cool finality of a game show host eliminating a contestant. Because the patient had no hemodynamic instability during his stay, and no ongoing bleeding, the hospitalization was deemed… unnecessary.

Denied.

“I cannot overturn the decision,” she said, as if quoting some higher order of evidence from randomized clinical trials rather than a faceless algorithmic edict she no doubt had up on her screen as she was talking with me.

I took a deep breath.

Then I asked her to imagine herself as the patient — sitting in the ER, post-recent surgery, with those symptoms and those lab results. Or better yet, as the clinician doing the initial assessment, deciding whether to admit or to send him home.

Would she have discharged this man? Would her judgment have changed if she weren’t now on the payroll of Giant Healthcare Insurance Company? Had she, like so many burned-out clinicians, left clinical medicine because of pointless, time-wasting demands like this conversation — only to end up perpetuating the same dysfunction from the other side?

No answer. Silence on the other end. Then, she repeated, “Thank you, Dr. Sax for your perspective. I cannot overturn the decision.”

Because of course, the outcome — the good outcome — was only apparent after the fact. One reason to admit people is when we don’t know if they’ll do well.

So yes, the patient got better. No, he was not critically ill. But that’s not evidence the admission was unnecessary; that’s evidence the admission went about as well as could be hoped. Isn’t that what we all want?

Unfortunately, our healthcare system now seems to reward retrospective omniscience more than clinical judgment. “If only you had known he wouldn’t bleed again!” they say. Right. And if only I had known to buy Nvidia stock when it first went public in 1999.

I’ll stop now — time to call my airline because my flight has been canceled due to an unexpected mid-summer blizzard. Should be more fun than this call.

Beyond frustrating and so so unfair.

Any idea the outcome regarding final bill, patient able to negotiate downward?

It is a upside down world. An Alice in Wonderland world.

I worked for one of these companies for a few months. It was awful.

I don’t know if this will make you feel better, but almost nothing you could have said would have reversed the decision.

Quitting this job was the best work decision I ever made.

While fear of litigation was not likely the reason for admission, it could be. Pt could have gone home and come back the next morning for reassessment–but our system isn’t really built to accommodate the chronically metastable unhealthy.

So, perhaps emergency admissions need to be pre-approved by the insurance. And if there is a bad outcome, then the patient should have the right to sue the insurance company.. Let the insurance companies take responsibility for the decisions. If the admission was denied up front, would the patient be willing to pay?

Health care is simply too expensive. And unhealthy people and their providers need to think twice before elective surgery and the fee for service providers need to provide better follow up for their metastable clientele–just wondering if he even had a post op visit with Hgb and creat?

This is not just the insurance company problem. It is the fee for service mentality.

this is a great idea. why aren’t we doing this already?

The “system” remains dysfunctional and frustrating. With profit motive and cut throat capitalism the mode for insurance company payment operation for health care, we are all stuck. In the regressive, deteriorating political milieu of the US with corruption, ignorance, and greed, the only meaningful answer of universal federal managed health care slips farther away.

If she couldn’t overturn the decision, why did she agree to a peer-to-peer phone call about it? If the patient had crashed during the hospital stay (one of many concerns of the admitting physician), the insurance company would have paid for the stay. This is the insurance company’s “armchair quarterbacking” of the admitting physician’s decision based on hindsight, which is an unethical loophole.

“It is only because of their stupidity that they’re able to be so sure of themselves”

From Kafka, “The Trial”.

Have you not heard the horror stories of socialized medicine? That is not the answer.

I write appeals letters to try and get these types of cases overturned after the fact. It’s maddening on the one hand, but on the other hand, can be very rewarding. I find I am writing letters against Medicare Advantage insurers 95% of the time. CMS is very clear that MA plans must make coverage determinations that are based on coverage criteria that are no more restrictive than Traditional Medicare.

42 C.F.R. section 412.3 dictates the criteria for inpatient admission and is commonly known as the two-midnight benchmark: “an inpatient admission is generally appropriate for payment under Medicare Part A when the admitting physician expects the patient to require hospital care that crosses two midnights.

(i) The expectation of the physician should be based on such complex medical factors as patient history and comorbidities, the severity of signs and symptoms, current medical needs, and the risk of an adverse event. The factors that lead to a particular clinical expectation must be documented in the medical record in order to be granted consideration.”

I use the exact language from the code. The trouble of course is that the insurance company will try to debate the “complex medical factors and the severity,” but I think if a reasonable argument is laid out with as much information from the chart, you can win. The admitting physicians also would help us out if they had a statement stating that they expect the care to span 2 midnights based on the complexity and severity.

In any case, good luck to everyone fighting the peer-to-peer battle and writing appeals letters. Go to the federal regulations and cite them back to the insurance companies and ask if they are willing to be non-compliant. I have found this to be helpful.

The other day I had to do a peer-to-peer for a patient who was still intubated and in the ICU because there was a delay in receiving the clinical documentation due to the holiday weekend. Despite the clinicals being sent on Monday and multiple confirmations that the clinicals were received, I was *still* requested to do the phone call. The denial was successfully overturned, but man what a waste of everyone’s time (me having spent about an hour on the phone waiting on hold just to *schedule* the peer-to-peer for several business days from my phone call during which they proceeded to play twenty questions with me to confirm I had the correct patient and being skeptical because the patient’s state of residence was not what was in their records, but that I couldn’t ask the patient about because he…was intubated…).