An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

September 22nd, 2023

Long-Acting Cabotegravir-Rilpivirine for People Not Taking Oral Therapy — Time to Modify Treatment Guidelines?

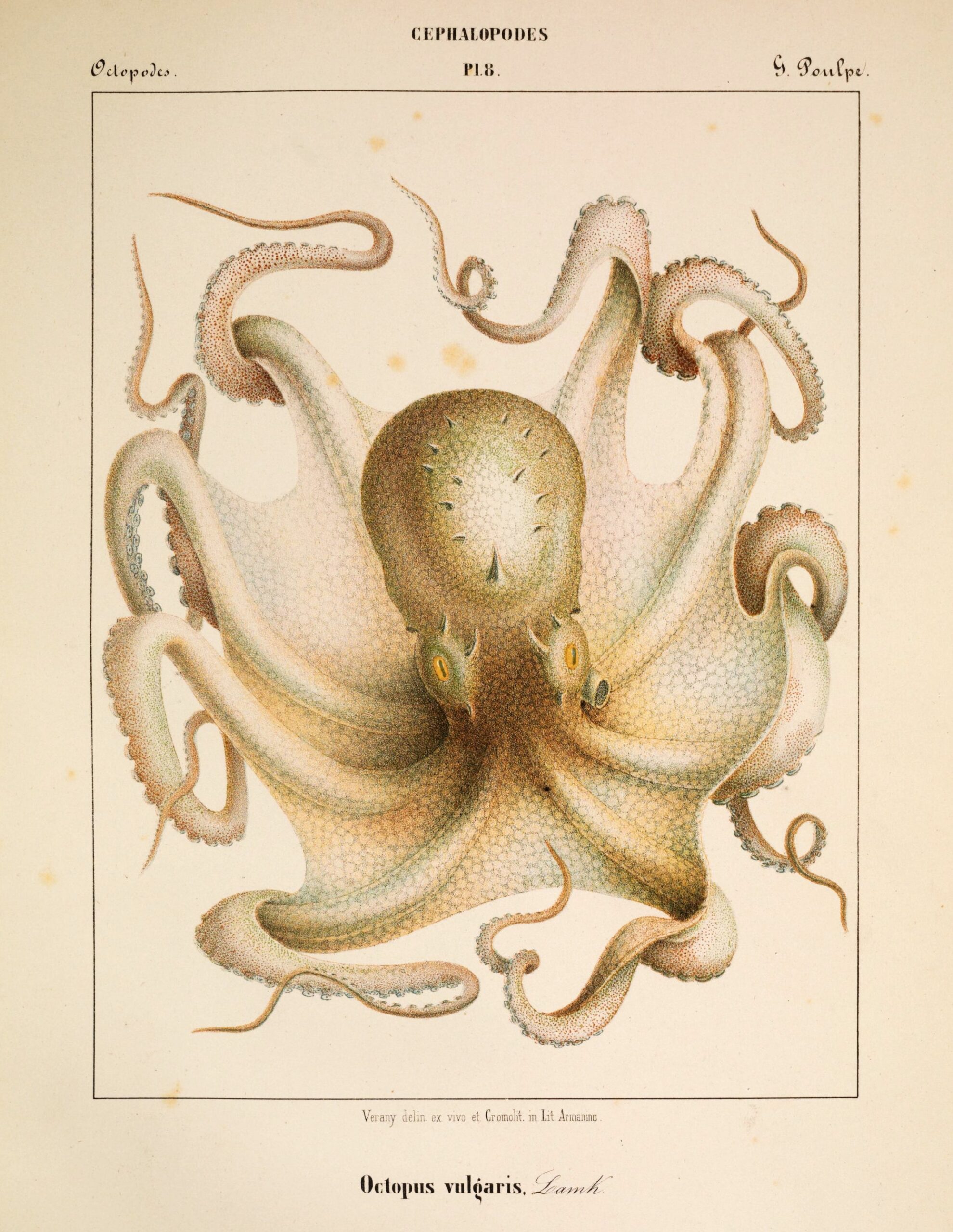

Cephalopods, by Jean Baptiste Vérany.

HIV treatment guidelines are understandably reluctant to endorse practices that have limited data. Having served on two such panels (previously, DHHS and currently, the IAS-USA guidelines), I totally get this — you don’t want to put a stamp of approval on strategies that may ultimately do more harm than good.

With the caveat that I cannot speak for the guidelines panel I currently serve on, I can give you my opinion on a topic much discussed among us ID and HIV specialists — namely, the use of long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine in people not taking standard oral ART, despite all our efforts to encourage them to do so.

Here it is:

If the alternative is untreated and progressive HIV disease, and the patient has advanced immunosuppression, we should stop discouraging use of this potentially life-saving therapy.

I base this on what are now a few published studies, including the original reports from UCSF, a follow-up from them with a larger sample size, a modeling analysis demonstrating substantial projected survival benefits, and now — just published in Clinical Infectious Diseases — a small case series from a different clinic with comparably excellent outcomes.

At a Ryan White-funded HIV clinic at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, clinicians began offering injectable CAB/RPV in February 2022 as a salvage option to people with HIV (PWH) who had viremia despite intensive case management strategies. Since that time, they have offered it to 12 patients — 7 women, 5 men. The baseline mean CD4-cell count was 233, and HIV viral load 152,657 copies/mL, with 5 of 12 having a history of AIDS-defining opportunistic infections.

With the caveat that follow-up is necessarily short, the results were excellent: All 12 achieved viral suppression within 3 months of treatment initiation, with no virologic rebound to date. They also reported good immunologic responses and high adherence to scheduled injections. These favorable results are all the more remarkable since some of the participants had NNRTI and INSTI resistance mutations, though none had full predicted resistance to either drug.

The experience with these dozen patients is now being reproduced anecdotally in small case numbers from other centers, including our own. While San Francisco led the way, this is doable in any HIV treatment clinic with intensive case management services.

Meanwhile, the DHHS HIV treatment guidelines continue to state the following:

The long-acting ARV combination of injectable cabotegravir (CAB) and RPV is not currently recommended for people with virologic failure [DHHS].

I strongly believe the time has come for us to revise these prohibitory statements (a similar one appears in the IAS-USA guidelines). Such statements may make it difficult for clinicians to procure this treatment for PWH whose treatment options (oral ART) otherwise just aren’t working. One can craft language with appropriate cautionary statements describing the unusual settings in which CAB-RPV is the best — and, importantly, the only — option for people with virologic failure.

Here’s a go at this:

Under rare circumstances, long-acting CAB-RPV can be an option for people with virologic failure when no other treatment options are available or effective. Such treatment must be accompanied by intensive case management and close follow-up. It should be limited to PWH who meet the following criteria:

- Unable to or cannot take oral ART

- Are at high risk of HIV disease progression (CD4 < 200 or a prior history of AIDS-defining complications)

- Have virus susceptible to both CAB and RPV

- Can be supported by intensive case management services

Sure, there will be cases where treatment failure with resistance occurs; where patients are lost to follow-up; where we will need to battle with payers to convince them to cover this non-FDA–approved indication; where the team of people (and it’s always a team) charged with case-management and medication administration spend enormous time and energy to no avail.

I acknowledge these issues and frustrations, but at the same time, ask — what is the alternative?

It can’t be to withhold the only regimen that might help them. Because as shown in the figure posted below, the median life expectancy for someone with AIDS in the pre-ART era — advanced HIV disease, no treatment — was less than 2 years.

When I was a medical resident and ID fellow, the median survival for a person diagnosed with an AIDS-related opportunistic infection was around 18 months pic.twitter.com/yXe37iDFgS

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) August 27, 2023

I think we’d all agree that this grim prognosis is simply unacceptable if we have an available effective treatment we’re not using.

I might replace “virologic failure” with “uncontrolled viremia” but agree with this proposal.

I agree with Dr. Sax; when oral therapy is inusable why we shouldn’t use the long-acting Cabotegravir-rilpivirine injectable combination?

I am in total agreement with your proposal Dr. Sax. I have worked in this field since 1991 starting off as an ACTG Pharmacist and then for the past 26 years as a Clinical Pharmacist focusing on HIV patient adherence and education. With regard to salvage therapy- I trained more than 80 patients in the self-preparation and injection of T20 many years ago which was a bridge to better and easier medication in the future. This did save several lives at that time. Now with the exciting long acting injection regimens I do feel that a number of patients could benefit from the use of these agents. Afterall, for many of our patients, HIV seems to be the least of their concerns at times due to food and housing insecurities as well as untreated and undertreated mental health and substance use issues. There are also patients who have swallowing issues as well as issues with the daily reminder of their disease when taking oral pills. For whatever the reason that a patient is unable to take or tolerate oral therapy, the ability to use these new long acting injectables could work miracles.

I couldn’t agree more with you, It is key to increase (and not limit) access to our different menu of options with safe and effective treatment regimens for all people living with HIV. There is no one-size-fits-all all.

THANK YOU! for recognizing the real-world scenarios that clinicians face in clinic (and how narrow guidelines can make it even more difficult for us to tackle them). Last year I started CAB-RPV as salvage for a patient who comes to clinic regularly but just CAN’T consistently take oral meds. This was after almost 10yrs of trying, with intensive Ryan White clinic team support, regular clinic follow up, and a long-term consistent trusted clinician relationship. We were just unable to overcome complex psychosocial factors at home, and it was frustrating and heartbreaking to see this man that we care about descend a CD4 <100 and worry what would happen next. When CAB-RPV it seemed like a great option but he was not undetectable so waited. Finally, I just documented very clearly that this was life-saving treatment and went ahead with CAB-RPV. He has been undetectable ever since.

Thanks for sharing this experience. Many of us have similar anecdotes.

We don’t need a two-armed, randomized clinical trial of this strategy vs standard of care, because in these struggling patients, standard of care has already proven not to work for them.

I do like the idea of a single-arm study to gather more information (and potentially to get FDA approval). Hope it succeeeds.

-Paul

Is there a specific viral load threshold where you would be particularly concerned about treatment emergent resistance, despite ontime injections? Such as >100k or >500k copies/mL. I know this is likely unanswerable based on how CAB/RPV has been studied.