September 11th, 2020

Emotional Intelligence During a Pandemic

Masood Pasha Syed, MBBS

“We are the keepers of each other’s future,” my program director said in her speech on our graduation day. These words have resonated in my mind and inspired me in laying the foundation for my chief residency year. We all have the opportunity and responsibility to teach and learn from each other. I remember the first day of my internship, where I felt like a sponge trying to adsorb or absorb as much as I could. And here we are, 3 years later, ready to take the reins — some of us as attendings, some as fellows, and, a few of us, as chiefs.

Living in a world with COVID-19, one can’t help but wonder what this means to the new residents and medical students stepping into medicine. Medicine never was and never will be an easy science. As residents and medical students go through training this year, learning to truly appreciate and internalize what it means to be on the frontlines will be a unique experience. Although there is a formal curriculum for residents and medical students, which is absolutely needed, we also must be mindful about giving our residents the best tools to work through the pandemic. One such tool is emotional intelligence (EI).

Emotional intelligence is the capability of individuals to recognize their own emotions and those of others, discern between different feelings, and use those feelings to guide behavior to achieve one’s goal(s). There is growing research and evidence that a doctor’s EI can influence his or her ability to deliver meaningful and compassionate patient care. But is EI is a trait we are born with or a learned skill that we acquire? I think it is a combination of both. Through this pandemic, I have found that we, as a medical community, are developing a stronger sense of emotional intelligence. To highlight this, consider the ‘Mixed Model Theory’ by the journalist/scientist Daniel Goleman which endorses five key elements that lay the foundation for EI: motivation, self-awareness, self-regulation, empathy, and social skills. I want to share this theory through medical binoculars with illustrations that I believe might help us become better physicians.

Defining emotional intelligence through the pandemic:

- Motivation – the ability to go on in life, despite obstacles or limitations one may have. One big concern we had earlier this year was the new interns’ experience as they were about to start training. Would they be able to start residency training on time? Could medical graduates travel nationally and internationally to their matched programs to train? Would their learning be compromised as we innovated through the pandemic (while socially distancing ourselves)? It takes motivation and commitment to leave everything and everyone in your life at home and move to a new location or country to train and work during a pandemic. Our program is diverse, with residents from 14 countries on 5 continents, which means that we must work within all those countries’ rules and regulations to have our interns join us this year. As we traversed through varying timelines in getting our residents to our program, we learned from all their experiences and journeys. I appreciated our interns’ motivation and dedication as they successfully began their training this past summer.

- Self-awareness – the ability to recognize one’s moods, feelings, skills, and limitations. Being self-aware is essential, as this also has an effect on our patients and the care we deliver. Going through the pandemic with a surging number of cases and losing patients to this illness warrants reflective debriefing and addressing one’s own feelings associated with it. Self-awareness is vital to reduce physician burnout while maintaining hope and optimism and seeing the light at the end of this tunnel.

- Self-regulation – the ability to use self-awareness to control one’s own impulses and recognize our impulses while caring for our patients. This pandemic brought with it limited visiting rights, which meant families could not meet their loved ones who were in the hospital. This regulation usually was met with understanding, occasionally with grief, and rarely with anger. Self-regulation for a healthcare provider in this setting means controlling one ’s response to this challenging situation and advocating the importance of social distancing in keeping family members safe.

- Empathy – “going the extra mile” is the ability to understand other people’s emotions and reactions. Being motivated and self-aware while regulating one’s own emotions allows one to be an empathetic physician. Through this pandemic, I have realized the power our words and actions genuinely have. Whether it was using your phone to Facetime patients’ family members to allow them to see their loved ones in the hospital, covering for your colleague who may be sick, or staying beyond your shift time to stabilize your ill patient — there have been numerous examples of nurses and residents going the extra mile. I cannot do justice to all their efforts and sacrifices, many of which go unnoticed. I am reminded of the following quote: “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” – Maya Angelou

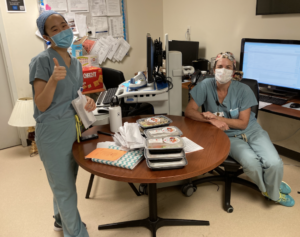

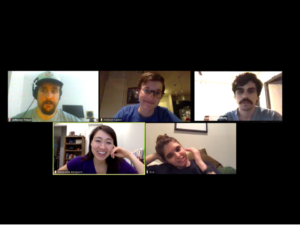

- Social skills – the ability to pick up social cues during our interaction, as we find common ground with others. Being socially inclusive while socially distancing has been a new way of life. The key has been to consistently innovate to supplement our lives through the pandemic for our education, learning, and social wellness. As an example, we have a wall in our department where we mount an annual picture of all our residents with the program leadership. This year might have been the first in which we would not have a group picture of all our residents. We had to innovate, while practicing social distancing — which resulted in what I think is the most exceptional picture of all time.

Our actions are a product of our mindset and ever-evolving perspective. Working through this pandemic has most definitely changed our perspective about caring for our patients and each other. As a chief resident, it is my honor to witness my residents’ and interns’ tremendous growth through training. Helping students find their true calling and meaning in their work is a rewarding experience for every educator. One such example for me is this poem penned by my intern, Dr. Vishesh Jain, as he worked through the pandemic and wrote about what it truly meant to him.

In conclusion, I appreciate all my colleagues (physicians, residents, nurses, nutritionists, physical/occupational therapists, case managers, EMTs, PCAs, other frontline workers) preparedness to show up to work — be it during a pandemic or not, no questions asked, no less heroic than soldiers walking into war. During these times, emotional intelligence is vital, as it adds meaning to our lives and helps reduce healthcare worker burnout while allowing them to provide the best patient care. As we continue to care for our patients, not knowing the long-term complications of this disease, we must not forget our power as healers. One cannot cure every ailment, but perhaps one can help heal it.

September 3rd, 2020

“Never Waste a Crisis”: Perspectives from History and Today

Holland Kaplan, MD

The mantra “Never waste a crisis” has stuck with me for the past several months. This statement was reportedly made by Winston Churchill in the 1940s, during World War II. However, a well-known internal medicine faculty member and leader at Baylor College of Medicine, Dr. David Hyman, who recently passed away, also gave us this advice in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic has taken so much from us. For some, it has taken away the lives of beloved family members, friends, and colleagues. For many, it has taken away financial security, jobs, the schooling of children, any remaining trust in our government, and the ability to enjoy a meal out at a restaurant. And, for all of us, it has taken away the life we knew before this crisis struck.

At my institution, the COVID-19 pandemic has seriously altered the way our hospitals, residency program, and individual lives function. Thankfully, we have not seen devastation to the degree that other cities experienced earlier this year. Nonetheless, even in the largest medical center in the world, I have witnessed hospital wards transitioned to intensive care units, rationing of masks and other personal protective equipment, shortages of high-flow oxygen machines, and reconfiguration of entire staffing models at both the faculty and trainee levels.

But there is hope that progress and opportunity can arise from any crisis, whether war, natural disaster, economic turmoil, or pandemic. And there is truth to the homage that, indeed, we should “Never waste a crisis.” Because out of the depths of any crisis can arise new ideas, previously unidentified opportunities, and real change. Below, I have identified five themes for making the most of a catastrophe. I have also provided examples of each item – one historical example and smaller-scale examples of how graduate medical education, in my residency program or at-large, has made progress in the setting of this pandemic.

1. Rapid innovation

Crises can prompt rapid innovation where there might have been none otherwise. Historically, World War I was an expansive and far-reaching crisis. Prior to this war, in the early 1900s, use of blood banks and blood transfusions was infrequent. The trench warfare of WWI resulted in particularly high mortality. During the war, blood transfusions became increasingly common, particularly as an approach for managing hemorrhagic shock prior to surgical intervention. Without WWI, the development of blood banking and blood transfusions as a standard of care might not have developed until significantly later in history (Transfus Med 2014; 24:325).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, almost all of our didactic time, including morning report, noon conference, didactic half-days, and simulation sessions have transitioned to occur virtually. Although there have been challenges with this innovative approach to learning, there have been positive aspects as well. Our morning report case sessions now regularly have over 100 attendees, including not only our own internal medicine residents but also faculty from across all of our pavilions, residents from other specialties (such as radiology and family medicine), medical students looking for additional learning opportunities, and prospective applicants to our program. This level of accessibility and exposure was simply impossible with our in-person conferences. The additional faculty attendance has made it easy to get a “consult” on a complex case in the moment during morning report. Our virtual noon conference has enabled us to create a recorded library of lectures. Thus, our residents are able to view any content they missed. Overall, this modality of learning has enhanced accessibility of our didactics.

2. New levels of teamwork and cooperation

Catastrophes have a tendency to force people to work together to overcome them. As a result of World War II, the United Nations became the most recognizable, powerful intergovernmental organization in the world. At its founding, the UN had 51 member states. It now is comprised of 193 states, including almost every sovereign state in the world. One can debate the effectiveness of various components of the UN, but this body represents the largest effort at global cooperation in history. Among a variety of other accomplishments, the UN facilitated the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. Without a crisis to promote its formation, the UN might not have been founded.

The degree of teamwork and cooperation I observed during the worst of this surge of COVID-19 in Houston has been inspiring. Our internal medicine residents cumulatively stepped up to provide over 1000 hours of additional coverage due to the extra patient load. Residents happily helped cover when colleagues were sick. On a larger scale, after our institution declared ACGME “pandemic status” we received innumerable offers of assistance from residents in other programs asking how they could help with the extra patient load. From gastroenterology fellows helping in our COVID unit to ophthalmology residents backing us up in the intensive care unit to surgical residents covering a multitude of medical ICU patients, this crisis gave us the opportunity to form relationships with people we otherwise might never have had the opportunity to work with.

The degree of teamwork and cooperation I observed during the worst of this surge of COVID-19 in Houston has been inspiring. Our internal medicine residents cumulatively stepped up to provide over 1000 hours of additional coverage due to the extra patient load. Residents happily helped cover when colleagues were sick. On a larger scale, after our institution declared ACGME “pandemic status” we received innumerable offers of assistance from residents in other programs asking how they could help with the extra patient load. From gastroenterology fellows helping in our COVID unit to ophthalmology residents backing us up in the intensive care unit to surgical residents covering a multitude of medical ICU patients, this crisis gave us the opportunity to form relationships with people we otherwise might never have had the opportunity to work with.

3. Needed systemic structural change

Disasters also have a tendency to spur on much-needed structural change. The 1918 influenza pandemic was the deadliest human event in history since the Black Death, killing 50 to 100 million people. Before this pandemic, the United States was woefully lacking in almost all public health measures. But by 1925, all US states participated in a national disease reporting system. Many countries started forming national health ministries in the 1920s, and ultimately, the World Health Organization was formed in 1946. This cascade of public health measures was brought on by the deadly pandemic of 1918.

In response to the surge of COVID patients in our county hospital, our intensive care unit was forced to increase its capacity. Prior to this pandemic, we frequently had a challenging volume of overflow ICU patients. However, due to the additional surge of patients in the pandemic, we were able to work with the critical care and hospitalist services to enlist additional assistance from hospitalists, ICU attendings, and critical care fellows for night and day coverage in the ICU. As a result, we have been able to establish a separate “teaching” ICU service that has a distinct patient cap. Without the pandemic, the impetus to have these discussions and form a separate team would not have existed.

4. Opportunities for improved communication from leaders

During great crises, people look to their leaders for reassurance and information. In response to the Great Depression, the greatest economic downturn in history, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted “fireside chats” to clearly communicate with the American people. The conversational, informational nature of these radio broadcasts served to reassure the country throughout multiple crises. Every president since Roosevelt has delivered periodic addresses to the American people, a tradition stemming from the disaster that prompted Roosevelt to enact his fireside chats.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for increased communication and transparency between leadership and our residents became evident. Social distancing forced us to utilize virtual approaches. Thus, we instituted twice weekly virtual town halls with our program director in addition to weekly “chief chats” with our chief residents. We provided an open forum for questions, in addition to soliciting questions beforehand. We also ensured there was transparency of information by posting daily updates on the COVID censuses at each of our hospitals, information that was otherwise not being provided. The virtual mechanism of these town halls made them more accessible, and the frequent communication enabled transparency about current events and future plans.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for increased communication and transparency between leadership and our residents became evident. Social distancing forced us to utilize virtual approaches. Thus, we instituted twice weekly virtual town halls with our program director in addition to weekly “chief chats” with our chief residents. We provided an open forum for questions, in addition to soliciting questions beforehand. We also ensured there was transparency of information by posting daily updates on the COVID censuses at each of our hospitals, information that was otherwise not being provided. The virtual mechanism of these town halls made them more accessible, and the frequent communication enabled transparency about current events and future plans.

5. Increased resiliency for the next event

Our response to a catastrophe lays the groundwork for our response to the next crisis. In Houston, we are particularly attuned to hurricanes as a form of natural disaster. One of the recent damaging hurricanes was Hurricane Rita in 2005, which resulted in widespread power outages. The company that maintains Houston’s electrical grid reported that, of their 1.9 million customers, 715,000 lost power during the storm. Since Hurricane Rita, this company has deployed new technology such as smart meters and intelligent switching devices to limit the number and duration of power outages. Additionally, they started a program to change wooden power structures to concrete and steel. These efforts are all in response to a severe storm in the hopes that fewer people will lose power in the next hurricane.

Through this surge of COVID-19 patients, I have witnessed the rapid expansion and subsequent compression of our county hospital’s capacity to handle the patient volume in concert with the flow of the surge. We worked to design surge protocols, integrate new COVID-specific units, and find appropriate coverage for an ever-increasing number of critical care patients. This process was done painstakingly, and there were triumphs and failures in our efforts. But above all, when we experience our next surge of COVID-19 patients, we will already have a framework in place for approaching the increased patient volume.

In Houston, we are thankfully in the latter part of this particular surge of the coronavirus. But with the uncertainty of vaccine timelines, limited public adherence to masking and social distancing guidelines, and minimal support from our government, it is impossible to predict what is to come. One thing I have learned from this COVID-19 surge is to “Never waste a crisis.” And hopefully, as a result, we’ll be better prepared for the next surge.

August 27th, 2020

“Use The Force”: How Do We Teach in the Operating Room?

Vivek Sant, MD

Dr. Sant is a General Surgery Chief Resident at NYU Langone Health, Bellevue Hospital, and Manhattan VA in New York, NY.

As I embark on my chief year in general surgery, the aspect I look forward to most is taking junior residents through operations. I am grateful to have had excellent teachers over the past 5 years, and I appreciate the opportunity to pay forward this mentorship. But taking what you have learned and teaching someone else turns out to be a very different challenge than learning itself! Suddenly, you realize your attendings have been doing a lot of behind-the-scenes legwork to make the operations look simple and to set you up for success.

For me, two things have set apart the best teachers: patience and communication. Patience is intricately linked with humility and remembering that “I too was in this position once.” In some ways, this is inherent to one’s personality and character; everyone can strive to be more patient, but I think this quality is hard to change. On the other hand, while everyone enters residency with different baseline communication skills, with self-reflection and practice, communication skills are amenable to improvement.

Communication is hard. The following three practices help me communicate better in the OR and make teaching more enjoyable.

Do the heavy lifting upfront

Many within the surgical education community encourage trainees and supervising physicians to have preoperative briefings to discuss operative approach and focus areas. I try to have this discussion with my attendings and have found it quite helpful to my own learning. When I operate with a junior resident, I try to discuss my game plan with them in advance, or send them my notes on the specifics of the procedure the night before. I have found that this elevates the level of discussion we have in the OR — from “how should we enter the abdomen?” to “here’s how you can optimally position your body, give better tension with your left hand, and make a cleaner incision with your right hand, in order to enter the abdomen more efficiently.” Instead of just learning what the moves are, we get to focus on how to do them efficiently.

Own the responsibility for understanding

One of my college professors used to say, “The responsibility for understanding should be on the teacher, not the learner.” So rather than asking “Do you understand?” he would ask, “Have I explained myself properly?” Taking a resident through a cholecystectomy, I tried to explain a set of moves to him: “Use your hook to get around that structure, turn 90 degrees, pull out, and burn.” “Uh-huh.” Something didn’t sound quite right, so I paused and asked “Just to confirm, does that make sense – what I said?” “Maybe not completely.” We were able to clarify, and the honesty was appreciated. As surgery residents, we become really good at saying “yes” — If someone asks us to get something done, we say “yes” and then figure out how to make it happen. Sometimes residents apply the same mindset in the OR and might feel reluctant to speak up when they are confused. In these situations, it is all the more important for the teacher to confirm that their directions are understood.

Tailor the approach to the individual and the situation

Tailor the approach to the individual and the situation

In these first 8 weeks of chief residency, I have become more attuned to the differences in personality, learning style, and experience among junior residents. In the OR, some residents appear very confident, whereas others are still finding their groove. Some have had more experience with certain procedures. Some respond very well to constant feedback, whereas others need encouragement. I myself have probably been in each of these positions at different points of residency! The best teachers understand that the needs of the learner are different for each learner — and in each situation! Modifying your teaching style constantly is hard, but once you figure out how to tailor your instruction, it is very gratifying to see your trainee achieve his or her maximum potential!

Despite my focus on clarity of communication, sometimes there are teaching moments that are beyond words and intellectual understanding. In the OR, one of my attendings occasionally exhorts, “Be an athlete!” It’s hard to explain exactly what he means or how it helps, but usually, I am able to re-attempt the maneuver with more agility and finesse! Last month when operating with one of my favorite attendings, I was struggling to laparoscopically drive a suture needle through a certain tissue into the right spot. He had me pause, he turned to me, and he said, “Use The Force!” The needle went exactly where it needed to go. Teaching and learning have a lot to do with patience and communication, but sometimes they verge on the realm of faith and understanding one’s heart!

August 19th, 2020

Residency Reflections from an Intern Gardener

Stephanie Braunthal, DO

Starting Our Garden

Last year, my boyfriend asked if I wanted to join a community garden. As he handed me the paperwork, he said he would be the “primary,” I would be listed as a “helper,” and for only $10, we could grow our own vegetables. Distracted by whichever rotation I was on, I agreed without much thought, assuming that “helping” would be something similar to a community service project. To me, a garden was some sort of greenery that already existed, occasionally needed upkeep, and in this case, would result in a crop-share. Needless to say, I was a bit confused about his fixation on choosing seeds and pre-planning the garden. I was even more surprised when we walked over on a misty mid-March afternoon, arrived at an overgrown 10 x 10 foot plot, and was told we needed to start weeding by hand.

Community gardening has provided a welcome source of activity and [distanced] socialization during the COVID-19 era. It has also inspired much reflection at a pivotal time in my career: the start of the pandemic, the end of residency, and the transition to chief resident responsibilities. Naturally, I have drawn parallels between them all.

Gardening (and Residency Training) Best Practices

To begin, like in medicine, best practices in gardening are hotly debated and change over time. As gardeners prepared their soil in March and April, they had seemingly endless conversations about the risks and benefits of tilling the soil, a practice that can be both beneficial and disruptive to soil health. My only contribution was telling the gardeners that they sounded like my fellow internists, grappling with whether the updated hypertension and aspirin guidelines could be applied to all of their patients, or to only those who were similar to the cohorts studied in the landmark trials. For those curious, we lightly tilled this year, added leaves to increase the organic matter, and will be doing “no-till” for the future. I am still not sure which strategy is the standard of care.

With our newly enriched soil, we were ready to plant. We had packets of seeds, shoots to transplant from one of my co-chiefs, and numerous gardening books from family members. We followed the instructions about depth, distance, and watering frequency. Then, we realized that, like patients, plants do not follow the textbooks. Similarly, their outcomes rely heavily on their environment. For example, our five kale plants were growing at equal rates for the first few weeks until the butternut squash vines took over a third of the plot and started blocking the sun. Then, the kale plant that had the most sunlight and rain grew the largest, and the others have been lagging behind, only to grow when we move the leaves out of the way. Competing weeds initially suppressed the carrots; once they were removed, the carrot stems shot right up. On the other hand, the corn, squash, and tomatoes have grown in spite of everything.

Structure Affects Function

A principle that is fundamental, but not unique, to medical education is that structure affects function. An example from residency that stands out is how adjusting one of our subspecialty rotation’s call schedules garnered better continuity of care, which ultimately engendered improved resident performance and morale. Even within our first month, my co-chiefs and I have observed residents’ successes and struggles. We are learning how to optimize our program’s infrastructure so that it can benefit a diverse group of learners. Just as my boyfriend and I figure out how often to water, weed, pare down, and transplant, my chief group is recognizing how to appropriately intervene and when to implement systemic change.

One of the most valuable aspects of starting this garden at the beginning of my chief term has been the unique opportunity to revisit the uncertainty, vulnerability, and insecurity that accompanies being a new trainee. In the garden, I am the intern, or maybe even the first-year medical student, navigating a new environment and grasping the vocabulary of an entirely foreign vocational language. My boyfriend and I constantly ogle our neighbors’ more aesthetically pleasing plots. Until recently, we assumed that others had years, if not decades, of experience. Much to our surprise, some of them only started last year. The imposter syndrome reminds me of being an intern, when becoming as knowledgeable or efficient as a senior resident seems like an unattainable dream. Yet, I can see the same pride from these new second-year gardeners that I do in our new seniors, and that I did in myself, realizing that they can independently manage a team and care for patients in a way that they did not think was possible a year earlier.

One of the most valuable aspects of starting this garden at the beginning of my chief term has been the unique opportunity to revisit the uncertainty, vulnerability, and insecurity that accompanies being a new trainee. In the garden, I am the intern, or maybe even the first-year medical student, navigating a new environment and grasping the vocabulary of an entirely foreign vocational language. My boyfriend and I constantly ogle our neighbors’ more aesthetically pleasing plots. Until recently, we assumed that others had years, if not decades, of experience. Much to our surprise, some of them only started last year. The imposter syndrome reminds me of being an intern, when becoming as knowledgeable or efficient as a senior resident seems like an unattainable dream. Yet, I can see the same pride from these new second-year gardeners that I do in our new seniors, and that I did in myself, realizing that they can independently manage a team and care for patients in a way that they did not think was possible a year earlier.

Growing Confidence

It is now early August, and we are starting to reap the fruits of our labor. The garden is growing on me. Although I wax poetic about the reflections it has inspired, the reality is that I was not enjoying it until I began to understand how and why things are done. Aside from a delayed appreciation for anatomy lab, I initially could not think of a parallel feeling during my medical training… then, I remembered I almost quit before it even began. Midway  through sophomore year of college, I had a sudden insecurity that I would not be able to get into medical school, which took the joy of learning out of any pre-med class that I was taking. I decided to take a semester to explore the myriad other intellectual avenues offered at small liberal arts colleges, later stressed about finishing the pre-med requirements before graduation, and subsequently enrolled in two biology and chemistry summer courses at a university closer to home. Whether it was a different teaching style, living with my family, or the exhilaration of being in a new school, something clicked. I left for study abroad confident in my ability to become a physician and returned to college that spring, eager to jumpstart the rest of my career. As for many in medicine, my journey has since been filled almost daily with peaks and troughs. Harnessing the reinvigorating moments has kept me going; the desire to teach others how to do so is part of what inspired me to become a chief resident. I look forward to the day I can bring some homegrown vegetables to guide the conversation.

through sophomore year of college, I had a sudden insecurity that I would not be able to get into medical school, which took the joy of learning out of any pre-med class that I was taking. I decided to take a semester to explore the myriad other intellectual avenues offered at small liberal arts colleges, later stressed about finishing the pre-med requirements before graduation, and subsequently enrolled in two biology and chemistry summer courses at a university closer to home. Whether it was a different teaching style, living with my family, or the exhilaration of being in a new school, something clicked. I left for study abroad confident in my ability to become a physician and returned to college that spring, eager to jumpstart the rest of my career. As for many in medicine, my journey has since been filled almost daily with peaks and troughs. Harnessing the reinvigorating moments has kept me going; the desire to teach others how to do so is part of what inspired me to become a chief resident. I look forward to the day I can bring some homegrown vegetables to guide the conversation.

August 12th, 2020

Welcome! Chief Residents for 2020-2021 Join the Panel

Charleen Hamilton

The editors and staff of NEJM Journal Watch warmly welcome our new panel of Chief Residents for the 2020-2021 academic year. This will be a challenging year for all healthcare professionals, and we are grateful that these five dedicated, talented, and busy physicians have agreed to share their concerns and triumphs with the NEJM Journal Watch community.

Our 2020-2021 panel:

- Stephanie Braunthal, DO (Chief Resident, Cleveland Clinic Foundation)

- Holland Kaplan, MD (Chief Resident, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston)

- Vivek Sant, MD (Chief Resident, NYU Langone Health, Bellevue Hospital, and Manhattan VA)

- Sneha Shah, MD (Chief Resident, VA Eastern Colorado Healthcare System)

- Masood Syed, MBBS (Chief Resident, Saint Vincent Hospital, Worcester, MA)

Good-bye, 2019-2020 Chiefs!

We will never forget our 2019-2020 panel, who bravely pushed on in the face of unprecedented changes in every facet of their professional and personal lives during 2020. We’ll always remember their stories of courage and their calls for social justice. Their concern with the wellness of physicians during residency (and beyond) and their tips and tricks for maintaining work-life balance inspired residents worldwide. So, thank you, Prarthna Bhardwaj, MD, MBBS; Eric Bressman, MD; Allison Latimore, MD; Daniel Orlovich, MD, PharmD; and Frances Ue, MD, MPH! We congratulate you on your resilience (and offer best wishes on your new marriages, babies, and professional accomplishments). Thanks for letting us have a glimpse into your lives.

Dr. Bressman is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, NY

August 5th, 2020

Can We Rename Resident Burnout, Please?

Daniel Orlovich, MD, PharmD

It is time we stopped framing resident burnout in a certain way. Let’s be honest, the current descriptions give us nothing to build on.

How is burnout currently framed?

In a strict academic sense, we are guided by clear, globally accepted definitions. We are familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and reduced personal accomplishment, as well as the various questionnaires and indexes.

However, in the real world, in the hospital and clinics, burnout is inevitably framed as something to be avoided. Burnout comprises three themes: The first says resident burnout can lead one to leave medicine and likely be saddled with debt. The second says that resident burnout might lead to an unhealthy path of addictions. And finally, burnout is framed as the ultimate endpoint — ending one’s life.

To be clear, all those topics are important and they are parts of resident burnout. However, my experience is that this tells us only part of the story. It instructs us on what to avoid and fails to inspire us with meaningful, actionable direction.

All of us in medicine intuitively comprehend this concept. Take for example, when we present a patient. We often invoke the fundamental teachings of pertinent negatives and pertinent positives. Simply, we report what is not there and what is there.

So, what is there, when we talk about burnout?

A simple answer, and one commonly given, is wellness. While the way we frame burnout is too negative, the way we present wellness is too vague. This cursory approach to wellness is akin to filler in our notes, a litany of boxes checked on the review of systems, and rambling when we present. In short, saying a lot while hardly saying anything.

So, I fully comprehend why the new interns, and other residents, aren’t eager to engage in the way that burnout and wellness are commonly presented. I don’t blame them. It is up to those of us whose interests include burnout and wellness work to present it a different way.

Let’s consider a new approach

My introduction to the concept of wellness preceded my acknowledgement of the official term. As an intern, I leaned forward in the stuffy computer lounge and zipped up my new navy fleece. I sighed as I noted that I was only 12% done with the modules. Then, I noticed a fellow intern stand up, grab his black backpack, and walk out of the room. How did he finish so quickly?

Is that the meaning of wellness — to finish orientation modules more quickly? Not quite. I must admit, that would be nice. But what I am saying is that my co-intern found a way to process and organize information quickly. And, that day in the computer lab was my first exposure to this talent, one that I deeply admire.

I saw first-hand, specifically, what organization meant. Instead of espousing generic benefits, like “work-life balance,” my co-intern showed me the concrete tangible aspects of wellness. Clinically, he was a tour de force. He would arrive after I did in the morning and still get done with rounding before I did. He was able to present in a methodical, coherent, and insightful manner. He anticipated questions and answered in a thoughtful way. While I was scrambling to update my notes he was enjoying a warm breakfast burrito and casually looking up studies. He carried an aura of appropriate confidence and found the humor in situations.

One day after signout, when he picked up that black backpack, I asked him if he had plans for the rest of the day. “I do,” he said. “I’m going apple picking with my girlfriend.”

At that moment, I realized he had wellness figured out. While my mind was stuck in avoiding the negative aspects of burnout he was reaping the rewards of a positive approach. He didn’t need to convince me — he was living proof. It was self-evident. A prestigious pedigree, a competitive specialty, stacks of publications, time to visit his family, and, yes, enough time to pick apples with his girlfriend.

My final take

When I tell people I’m interested in resident burnout, invariably the discussion turns to the negative aspects. In my experience, these are well known — but unconvincing. Then I usually pause for a bit. I ask them to name the upsides, the advantages, the benefits they’ve experienced first-hand from habits that lead them to be well. I make it a point to avoid the word wellness. Instead, I want to hear what that vague concept specifically means to them. While there are common foundations of wellness, how it is applied to each person is unique.

Wellness is a competitive advantage in our ever-competitive medical training: It applies to test-taking, applying to specialties, residencies, fellowships, places of employment, receiving evaluations, and interacting with staff. Wellness restores the awe we experienced when we wrote our personal statements. Wellness allows us to recognize, really recognize, the profound meaning and privilege we share in taking care of another human being. Wellness is a performance boost. And, for the sake of our own humanity, as humans, it is a basic saving grace.

Allowing us to pick apples with our loved ones.

Interested in a new take on resident burnout? After a two year-grant I distilled up-to-date practical solutions from over about 275 studies in an easy to read book here.

July 22nd, 2020

Patient Death and Physician Grief

Prarthna Bhardwaj, MD

A few months ago, one of my colleagues spoke about ‘Patient Death and Physician Grief’ at a morning conference — somewhat unusual, considering our conferences largely revolve around medical topics. I was stunned by how the next hour unfolded that morning.

The session started off like a traditional morning report with an opening line of the case. Except, we did not dive into a differential diagnosis or dwell on clinical reasoning. The resident spoke about a teenager who had presented after an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. He had died, despite the best efforts of a solid team. It had deeply affected the resident, as he missed the opportunity to fully process it on a busy night.

The first activity for the session involved desk partners sharing stories of patient deaths that affected them. Every single resident shared a story. Even normally quiet residents were suddenly talking.

I will embarrassingly admit that I cried a little, recalling one cold winter Thanksgiving day when my patient — a young woman with a toddler, had died of a brain bleed that was too deep for intervention. I took care of her for less than 24 hours, with no opportunity to connect with her as she was comatose on arrival to the hospital. Yet, that one incident affected me so deeply that I vividly remember every detail from that day, 2 years later. I tried to reason out why it affected me — was it because she was nearly the same age as me? Was the sorrow too difficult to bear during the holiday season? Was it the haunting image of her baby’s hushed sobs echoing along the walls of the empty hallways of the medical ICU? Or was it simply hormonal?

I looked around and saw a lot of tears as residents shared their experiences with the larger group. In that 1 hour, everyone allowed themselves to be vulnerable while recounting difficult experiences of taking care of patients who had died and how they coped with patient death. Even though we have mental health support and spiritual services in place at our institution, no one had paused to seek help to cope.

“Never get close to your patients”

We repeatedly read these lines in books and watch it on television medical dramas! The hidden curriculum of this stoic profession teaches us to distance ourselves and create protective boundaries. Feeling and displaying too much emotion is regarded as unprofessional and a sign of weakness. As Dr. Elaine Kasket from London Metropolitan University eloquently stated, “It feeds into this popular image of the physician as some kind of superhuman ultimate rescuer of human life; unable to do his or her job if they give in to or even acknowledge their emotions.”

This notion was perhaps also born out of the necessity to shield us from the constant emotional brunt associated with poor patient outcomes like death. However, are we really shielding ourselves from the emotional toll if we maintain our distance?

As trainees, we are thrown into a strange world in which death is often an unwanted visitor. Although it is a frequent visitor, each experience is still jarring. While feelings of grief are normal when we lose patients in our care, they can simultaneously be confusing and even uncomfortable. Clearly medical school has not prepared us for this possibility. However, it is imperative for us to ‘heal’ promptly to go back to doing what we purpose our lives around – saving patients!

Why do we need to validate feelings of grief?

In a nutshell, unprocessed or disenfranchised grief is traumatizing. Feeling like we aren’t living up to society’s unwritten rules about grief can lead to isolation, shame, and guilt. Our profession punishes doctors for grieving and restricts the medical licenses of those seeking mental health care. So rather than process grief, many physicians turn to alcohol, drugs, or firearms. This, in turn, diminishes personal well-being, resulting in moral distress and soaring physician suicide rates.

At the helm of a raging pandemic, this is an even more pervasive issue — healthcare professionals across the globe have recounted countless horror stories of patient deaths. This will no doubt have dire consequences in the years to come on the mental health of our community.

We have to do better

Adding a suicide help line and starting wellness committees are far from a systemic cure. It is a start, but we need more concrete steps to support physician trainees through this process.

1. A weekly debrief for all teams

Every program should have a consistent plan in place for a weekly debrief for all teams. This is especially important in the intensive care units. Feelings of grief need to be discussed freely and openly. Attending physicians ideally should take the lead to initiate these debrief sessions, which could help normalize this process.

2. Self-Reflection

My program designed a self-reflection curriculum that allows trainees to indulge in the practice of deliberate self reflection. Although this might not suit everyone, it helped several trainees tune in to their inner self. Various activities like journal writing, artwork, and group debriefs have allowed us to slowly but willfully identify our deepest fears and our proudest accomplishments. It has also been strangely gratifying to learn that we can come from different countries, backgrounds, and cultures and yet face the same struggles about patient death.

3. Mandatory Therapy Sessions

Having the option of professional mental health services is simply not adequate. Physicians are terrible about voluntarily seeking help. Every residency program should have mandatory in-house and free therapy sessions for their trainees at least 2 times a year. We need to normalize this process to avoid instilling feelings of guilt and inadequacy among physicians. ACGME, I hope you are listening.

A picture is worth a thousand words: A picture (that went viral on Reddit a few years ago) of a young ER doctor overwhelmed by grief after losing a 19-year-old patient

As the hour long session on ‘Patient Death and Physician Grief’ ended, despite the melancholy, all residents left the room feeling better than when they entered. As one of them put it, sharing stories with “someone else who gets it” was therapeutic.

None of us will forget the first patient who died under our watch, because knowingly or unknowingly, they are a part of the physicians we are today. For too long, we have been encouraged to stifle our feelings and to toughen up. Instead, let’s acknowledge our sense of loss and learn from it. After all, it is the human thing to do.

*Some patient encounter details have been modified

July 16th, 2020

Well, Did You Learn Anything?

Allison Latimore, MD

Dr. Latimore is the Education Chief Resident at the MedStar Washington Hospital Family Residency Program in Washington, DC

When I told my friends that I was going to be the Chief of Education for my residency program, they were stunned. How can you be a chief resident as a second-year resident? Isn’t that going to be a lot of work? How can you juggle it all? These were all valid questions that I even asked myself. How am I going to plan lectures, plan my own wedding, learn how to be a senior resident, support the interns, and manage my personal life? Then, a little global pandemic was sprinkled on top. The truth is: I struggled. My wedding ended up being canceled due to the pandemic. Lectures were planned, but some slots required improvisation. There were moments where I felt so defeated, but there also were moments where I felt so accomplished. There was a time that I was faced with adversity and sought guidance from my mother. She said, “Well, did you learn anything?” My mother had an excellent point. I faced challenges this year, and I learned a lot.

-

As a chief, you are not above learning or correction

You are still a resident. You are still in this program to learn. You are still in training and will get things wrong. You might not manage a patient the way that your attending would. You might miss something. Chief does not equate to perfection. In this role, you have to be willing to lead and to be willing to be taught. You have to know when you are in over your head and when to ask for help.

-

Calendars, reminders, and planners are your best friend

Administration is a large part of the chief role. It is impossible to keep all tasks and meetings in your head. To avoid forgetting things, keep a planner or use your smart phone to your advantage. As soon as someone would give me a new task, I would immediately put a reminder in my phone.

-

Conflict resolution skills can always use development

As physicians, we get conflict resolution training often and it might seem redundant. As a chief, your colleagues will come to you about different situations. You need to know when someone actually wants advice or just an ear for listening. You should be ready to give objective advice when asked. It is hard to be completely objective when you are still in a resident role, but you have to try your best to understand the different perspectives. Even if this means disagreeing with your colleagues.

-

Things will not always go as planned

Having to cancel a wedding due to a pandemic is an extreme example, but you have to be flexible. As a chief, last minute changes will come up and you have to adapt. Be ready to be called in to cover people. Be ready to manage lecturer cancellations. Being willing to step in when things are going awry is one of the biggest parts of the job.

-

Make the most of this experience

Being a chief is an honor and a privilege. Use this opportunity to grow as a leader, a physician, and an educator. Build your resumé during this time. Attend conferences when the opportunity is available and use your administrative time wisely. Most importantly, represent your fellow residents as you would like to be represented and maintain your role as a liaison between faculty and the residents.

Do you have any tips for chief residents? Please leave some advice in the comments below.

July 1st, 2020

Dual Crises and the Call for Resident Unionization

Eric Bressman, MD

Dr. Bressman is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, NY

On March 20th, as the chaos of the unfolding pandemic enveloped New York City, Governor Cuomo issued Executive Order 202.10, which, among other directives, temporarily suspended work hour restrictions for medical residents in New York State. These regulations, which had been enacted 30 years prior, were the consequence of the journalist Sidney Zion’s well-publicized crusade to investigate the tragic death of his daughter Libby at New York Hospital in 1984, which he attributed to the mistakes of overworked and under-supervised residents (N Engl J Med 1988; 318:771). A grand jury was convened, and although it did not indict any of the physicians involved in Libby’s care (as Zion had hoped), it did, in effect, issue an indictment of graduate medical training in the U.S. Depending on who you asked, it was either an educational system intentionally designed around long hours and self-sacrifice or exploitation of cheap labor at the hands of hospitals.

The grand jury’s recommendations, along with the subsequent Bell Committee report, paved the way for resident work hour limits as we know them today. Revisiting the literature from that time, it is clear that a campaign for reform that was sparked by concerns over patient safety, was in equal measure driven by concern for resident wellbeing (N Engl J Med 1988; 318:775). In the ensuing decades, we would begin to recognize that these parallel concerns were interconnected (BMJ Open 2017; 7:e015141).

This movement for reform, however, didn’t start with the Libby Zion case, and it didn’t end with the institution of duty hour limits. In 1975, the house staff of Cook County Hospital in Chicago went on strike for 18 days after months of dead-end negotiations. They successfully earned a (modest) pay increase and a reduction in their work week from 100 to 80 hours, by decreasing the frequency with which they had to take overnight call to 1 out of every 4 nights rather than every 3.

Students or Employees?

This was not the first organizing activity by residents, but it garnered the most publicity, and it fueled a debate that continues to this day: Are residents students or employees? In 1976, in the wake of the successful strike in Chicago, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that residents were in fact students, denying them the protections provided under labor relations laws, including the right to form a union. In their interpretation, residents’ primary purpose was to gain further training and skills, as evidenced by the many conferences, lectures, and rounds in which they partake. Their direct patient care is simply a means of learning, and their pay is nothing more than a living stipend.

It took 22 years for this ruling to be overturned, in a similar case involving house staff at Boston Medical Center. While not much had changed in the merits of the competing arguments — residents were still labeled with an intermediate status of “student-employees” — the environment clearly had, perhaps aided by the optics of two residents being tried for malpractice on a very public stage in the Zion case. Despite this decision, approximately 15% of house staff nationwide are currently represented by the Committee of Interns and Residents — the country’s primary house staff union — and the “student versus employee” argument continues to be litigated.

The Reality

COVID-19 came along and laid bare what had long been obvious to most observers: Residents might be learners, but they are — first and foremost — employees, and essential ones at that. As the tidal wave of the pandemic engulfed many teaching hospitals, the presentation of lectures, conferences, and most other formal teaching activities necessarily ground to a halt, and fears of a depleted workforce compelled suspension of various limitations that traditionally protect residents from being overworked. New York State, as noted above, lifted work hour restrictions. The ACGME, to their credit, insisted on preserving work hour limits, but suspended most other restrictions, including limits on the number of patients a single resident can care for at a given time.

COVID-19 came along and laid bare what had long been obvious to most observers: Residents might be learners, but they are — first and foremost — employees, and essential ones at that. As the tidal wave of the pandemic engulfed many teaching hospitals, the presentation of lectures, conferences, and most other formal teaching activities necessarily ground to a halt, and fears of a depleted workforce compelled suspension of various limitations that traditionally protect residents from being overworked. New York State, as noted above, lifted work hour restrictions. The ACGME, to their credit, insisted on preserving work hour limits, but suspended most other restrictions, including limits on the number of patients a single resident can care for at a given time.

In the wartime language that has become popular during this pandemic, hospitals formed “deployments,” and the backbone of the “front line” was undoubtedly the residents, working alongside their nurse practitioner and physician assistant colleagues. The difference was that their fellow soldiers had pre-existing collective bargaining agreements, with arrangements for overtime pay and channels to negotiate hazard benefits, whereas most residents were left to hope for the good will of their employers, with varying results.

The Imperative

The pandemic has highlighted not only the right of residents to organize, but also the necessity. As employees, residents are the very definition of vulnerable. During the recruitment process, they are deprived of any negotiating power by the Match, which precludes multiple offers and the leverage that comes with this. And, at the end of the day, they need the hospital more than the hospital needs them. Whereas other employees who are dissatisfied with working conditions, benefits, or other aspects of their jobs have the freedom to quit and seek employment elsewhere, residents need to finish out their program in order to receive certification and licensure, and the process of seeking a new position can range from onerous to impossible. When a crisis hits, as we just learned, working conditions can change dramatically overnight, with no obligation on the part of hospitals to adjust benefits or pay.

This is the most straightforward function of unions — giving a seat to the disenfranchised at the negotiating table — but historically, this has not been their only role. During the 1975 strike in Chicago, residents advocated not only for themselves, but also for their patients. They successfully negotiated patient protections, including readily available Spanish interpreters. In the ensuing years, the need for translation services has been recognized as so fundamental as to have been written into law in various patients’ bills of rights.

As a disenfranchised voice, residents have long been a voice for the disenfranchised. For a number of reasons, they have generally seen the injustice and inequity in our healthcare system earlier and more clearly. For one, they are not beholden to the financial structures that are very often the driver of these disparities in care. They are also on the ground, directly interfacing with patients of all backgrounds and in multiple contexts, and witnessing the kind of stratified care that has long been the norm in our healthcare system — one clinic for the privately insured, another for those on Medicaid, and a third for the uninsured. They are the only substantial part of the physician workforce that might split their time between private and public hospitals. This unique perspective helps them put the lie to the notion of separate but equal care.

There are many reasons health systems have historically resisted house staff unionization. It is far more convenient to present the terms of a contract than to negotiate them. There might be some discussion, but there is no need for lawyers or mediators or endless bargaining sessions. As short-term employees, residents are often viewed as interlopers at the policy-making table, not necessarily having the long-term interests of the institution at heart. There are fears, of course, of work stoppages, although these are rare (Chest 2014; 146:1369) and as anathema to residents as they are to administrators.

At this turbulent moment, however, as we grapple with the dual crises of an ongoing pandemic and the infrastructural racism that pervades every layer of our society, including the healthcare system, there has never been a more important time to empower the voices of residents. They are needed to help navigate a path toward greater justice — for themselves and for their patients. The only way to legitimize that voice, to give it a strength that cannot be ignored, is through collective action. The environment is primed for it; the moment demands it.

June 24th, 2020

Top 10 Tips for New Interns and Residents in the COVID Era

Frances Ue, MD, MPH

The month of June is traditionally an exciting time of transition across the country. A time where we welcome a new class of bright-eyed interns, and say goodbye to our senior graduates — who have become shining stars and leaders in our communities.

This year, however, is unique, with the start of the new academic year coinciding with an international pandemic — COVID-19. New interns might be feeling especially nervous and unprepared, as in-person medical school rotations were abridged in the spring. Rising junior and senior residents, the leaders and workhorses during the surge of the sickest of the sick, are likely feeling weary and are hoping for respite and recovery.

The start of the year is also mired by uncertainty. Uncertainty about when the next surge of COVID-19 patients will occur (modelling has been done at the Harvard School of Public Health by Drs. Yonatan Grad and Caroline Buckee); uncertainty regarding in-person curriculum turned virtual; uncertainty about how to effectively build community in a virtual space. To add, strife and conflict in the world around us is targeting the core underpinnings of our society and, arguably, humanity: injustices and inequities in race and access to healthcare.

Despite all of this, there is an overwhelming feeling of hope and energy. Now more than ever, we welcome these new doctors at a historic time. Residency training provides an avenue to not only learn clinical medicine, but also to develop as advocates and leaders. As I reflect on my leadership role as Chief resident this year, I’d like to offer some thoughts on what it means to train in the COVID-era. Not surprisingly, the principles of residency training remain the same.

Using research for advocacy at the Society for General Internal Medicine during my intern year (April 2017).

To the new interns:

- Stay curious. Try to learn at least one new thing from every patient.

- Spend time with patients; their stories will rejuvenate you. Learning to efficiently and effectively complete notes and tasks will help provide space for this.

- Seek feedback and spend time to reflect on your practice. Creating a habit of regular reflection will help you build your clinical reasoning skills. Specifically, debriefing rapid responses and codes in a structured way has been shown to improve emotional well-being of providers and future patient outcomes.

- Be kind to your multidisciplinary team — e.g., nurses, respiratory therapists, medical assistants, unit secretaries, case managers. They are here for you and have a wealth of knowledge and experience.

- Take time for yourself and for things that are important to you. Do not neglect to build your physical and mental health.

- Find your community in your tribe of interns and residents. Identify mentors early on; for example, find senior residents and faculty who can help guide you.

- Lastly, be present and enjoy every moment of this experience! I have come to find truth in the adage, ‘the days are long but the years are short.’ Don’t let these moments in your formative development pass you by.

To the rising junior residents:

8. You survived and thrived during a very difficult intern year amidst a global health crisis. Take time to reflect and rest, as you transition to your role as team managers and teachers. Remember to continue to foster your own growth and learning, as you guide new interns.

To the rising senior residents:

9. Your last year is an opportunity to add the finishing touches to your portrait as a resident physician. You have gained a depth and breadth of experiences during your last 2 years of training. I challenge you to be mentors and leaders in your program. Lead by example; the interns are looking up to you.

To the graduates across the country:

10. Congratulations! You certainly deserve it. You have shown your clinical acumen and grit, all while inspiring others around you. We are so proud of how your class came together in the face of adversity and can’t wait to see all the good you will do in the world.

It has been an honor and privilege to serve as Chief resident for our residency program and hospital this past year. There have certainly been many successes matched with unexpected challenges. Throughout, I have come to reflect on the following quote on leadership:

“We must be silent before we can listen. We must listen before we can learn. We must learn before we can prepare. We must prepare before we can serve. We must serve before we can lead.” – William Arthur Ward

Do you have advice for new interns and residents? Feel free to leave a comment below or tweet at me @UeFrances.