November 3rd, 2017

Uncuffing Medicine from Guidelines

John Junyoung Lee, MD

John Junyoung Lee, MD, is the 2017-18 Chief Medical Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Miami at Holy Cross, Fort Lauderdale, FL

During my first Cardiology fellowship interview, Dr. Schevchuck, one of the cardiologists on the admissions committee, opened the interview with the following question: “Guess how many guidelines there are in the United States?”

If you are reading this and you are planning on applying to a cardiology fellowship too, I have done some homework for you. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), about 1732 active guideline summaries have been published in the U.S. since 2000.

The opening question stimulated an interesting conversation, during which Dr. Schevchuck shared an analogy pertaining to the relationship between guidelines and physicians. He said, “imagine a commercial airline pilot and a 1000-page manual about flight rules. If flying and navigating an aircraft were entirely dependent on the pilot’s ability to recall every single word in the manual, then the commercial airline industry would be facing greater troubles than disgruntled customers on overbooked flights.”

Silver Bullets

In 2004, the New York Times reported that some clinicians were not following clinical practice guidelines, and the public’s response spurred what we now refer to as core quality measures. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) — a federal agency that administers the Medicare program — decided to attach quality measurements to common afflictions, and they mandated that the measurements be met for medical reimbursement. As a result, organizations and clinicians are now rewarded or penalized based on how carefully clinicians follow the guidelines. This system is founded on the faulty belief that adherence to guidelines is a “silver bullet” to decrease all-cause readmission and mortality.

In 2004, the New York Times reported that some clinicians were not following clinical practice guidelines, and the public’s response spurred what we now refer to as core quality measures. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) — a federal agency that administers the Medicare program — decided to attach quality measurements to common afflictions, and they mandated that the measurements be met for medical reimbursement. As a result, organizations and clinicians are now rewarded or penalized based on how carefully clinicians follow the guidelines. This system is founded on the faulty belief that adherence to guidelines is a “silver bullet” to decrease all-cause readmission and mortality.

These solve-all guidelines are sometimes pitted against physicians’ clinical judgments; and slight aberrations from guidelines could now be punished legally. Depending on whether one believes the COMET study or the MERIT study, a physician could be thrown into a legal battle over use of metoprolol tartrate or metoprolol succinate.

Medical guidelines are supposed to help physicians, right?

Guidelines can serve as general checklists that clinicians use to meet “core measures.” However, guidelines must be viewed with discernment, as they are not always apace with the newest research discoveries, and they sometimes make recommendations that are bigger than the evidence. Organizations, clinicians, and the public must remember that guidelines are, after all, guides, which cannot be substitutes for clinicians’ judgment and acumen.

In the past several years, guidelines have been used not as a tool for clinicians to educate themselves and help their patients, but as a tool to micromanage and attack physicians in the legal battles. I believe that, to move forward, we need to simplify and better delineate the standards of practice and designate a knowledgeable governing body to administer the standard. We also need to define acceptable degrees of freedom from the standards. While I understand that guidelines attempt to curb the behaviors of those few who practice “scary medicine” and put patients’ lives in danger, guidelines are also intended to inform clinicians about best practices. In order for physicians to actually benefit and not be harmed by the guidelines, I believe we need freedom to interpret the guidelines in the setting of our own patients, and we need better legal protections when reasonable judgment conflicts with a guideline recommendation.

What are your thoughts?

October 17th, 2017

Be Human. Be Memorable.

Karmen Wielunski, DO

Karmen Wielunski, DO, is a 2017-18 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, WI

My dad died on May 11, 2003. It was Mothers’ Day. I was 18 years old. Those are the easy facts. The more difficult ones are those detailing the events that led to his death. My dad was so many things — a brilliant geologist, a loving father, an inventor, a pilot, and a Vietnam veteran — to name a few. He survived three tours on the front lines in Vietnam, but he didn’t come out unscathed. He was a victim of post-traumatic stress disorder and, subsequently, progressive alcoholism. Despite numerous attempts by my family to help him, and treatment in every form imaginable, we watched a truly amazing person become engulfed in a vortex of pain and sadness. One night he fell. There was intracranial bleeding, seizures, and then irreversible hypoxic brain injury. It was  traumatic, unexpected, and life-changing for me and many others.

traumatic, unexpected, and life-changing for me and many others.

Memories and Questions

I started residency more than 10 years later. Just like every other resident, I spent busy days and nights in the hospital caring for countless patients with umpteen ailments. I also spent a lot of time working in the ICU. Unsurprisingly, my ICU patients frequently triggered recollections of my dad’s last hours in a similar setting. I very vividly remember him lying on an ICU bed connected to a ventilator. He was slightly turned on his left side, and had thick, white dressings around his head. I remember a nurse entering his room and quietly saying, “Tim, I’m going to give you some Tylenol now for your fever.” At the time I thought it was odd that she was explaining this to him. At 18 years old, I knew what ‘no meaningful brain activity’ meant, and I knew she did too. But, at the same time, her gesture was comforting to me.

The more I cared for critically ill patients during residency, the more I started thinking about the providers who took care of my dad. I wouldn’t call it critical thinking by any means — more like nonchalant, stream-of-conscious thinking as I walked from one patient unit to another. I wondered, ‘Were there internal medicine residents similar to myself? Were they really tired? Was there a critical care fellow? If so, was he or she a jovial fellow? I hope so – I like jovial critical care fellows.’ These random thoughts continued for years. But, the more I wondered, the more apparent it became that I actually didn’t remember any of the physicians who took care of my dad. The only person I remembered was the nurse who gave him Tylenol. Initially, this was a surprising realization. In a situation where likely countless physicians, residents, students, and therapists participated in my dad’s care, how was it possible that I only remembered one person?

Humans and Answers

The answer actually came to me via Twitter. In a post on September 22, 2017, Mark Reid, MD (@medicalaxioms), wrote, “When you run out of doctor things to do for the sick person, see if there are any human things you can offer.” Though seemingly simple advice, this resonated with me. It reminded my of my dad’s nurse. Due to the severity of his injuries after his accident, we quickly ran out of medical things to do. The nurse, however, still took it upon herself to do human things. The Tylenol she had to give was medically useless, but she used its administration as a venue to express care from one human to another. She called my dad by his name. She explained to him what she was doing and why she was doing it, and she didn’t judge his situation. Even her soft tone of voice was a much-needed juxtaposition to the chaos that had occurred up to that point. Even if it took me years to fully realize it, all of this mattered to me. Actually, it still matters to me now.

I’m sure that the other members of my dad’s care team were also great. I realize that circumstance and time likely also play large roles in my inability to recollect specific people at that time. However, I do think the concept of ‘doing human things’ is important to remember throughout medical training and practice. Our chosen careers often place us in a position of being participants in difficult, life changing events of patients and their family members. We won’t always have the answers. Even when we do have the answers, we won’t always have the solutions. But, we can always be human. And, as I can attest, even the smallest human acts can have a lifetime of impact.

Check out this NEJM article for a great review on post-traumatic stress disorder

October 6th, 2017

We All Give Up Something

Cassie Shaw, MD

Cassie Shaw, MD, is a 2017-18 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Saint Louis University Hospital in Saint Louis, MO

We all give up something, usually many somethings, to become doctors. It all starts with medical school where we spend hours listening to lectures, studying books, reviewing slides and reading notes. It continues into residency where we have little control over our schedules, working weekends and holidays; cherishing each of our 4 days off per month. We miss birthdays, weddings, family gatherings, and reunions. Instead of spending holidays with our own families, we spend them with our patients and their families. After completing my first 2 weeks as an attending, I quickly realized that the 24 hour per day work while on service is unforgiving. I would wake drenched with sweat after a panicked nightmare about a missed diagnosis. I would check charts right before bed and first thing upon awakening.

Thankful for generous attendings who donate their Cardinals season tickets to poor, tired residents. This outing was a definite plus in the sanity column.

However, as I write this, I hear the words of my Program Director in my ears: “no one wants to listen to a physician whine.” He’s right. Being a doctor is a sought after, respected, and well-compensated position. I wanted this. In fact, I made deals with the universe for years to get where I am today: “I will study every single night if you just let me into medical school.” No matter the sacrifices required, I still want this, and I cannot imagine doing anything but exactly this. It’s not just that no one wants to listen to a doctor whine — we aren’t alone in this sacrifice. Many of our colleagues in other health professions and non-health professions sacrifice as well. Right or wrong, in this country, we often put our profession first and allow family, fun, and free time to fall in line thereafter.

So how do we deal with the losses of days, hours, and important events with our loved ones? How do we stay sane and have lives outside of the workplace? As kids say these days, how do we fight the FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out)?

Until this year, I thought that I had created a good work-life balance. For instance, while I was in residency, I averaged one concert per month. It didn’t matter if I was post call, pre call, or had to be at the hospital at 5 AM the next day, if there was an artist in town that I wanted to see, I was at that concert. I sacrificed sleep for sanity. I thought I was doing it right: living a perfect balance of both work and life. However, I still let a lot of other things that made me happy fall to the wayside. Namely, I rarely read for pleasure; I picked up a book only long enough to read a few sentences before falling asleep. I changed that during my chief year. I got a library card, and I started reading again. I also joined a book club where I could surround myself with individuals who also wanted to nerd out over literature. This was probably the first time in years where I came to a table and discussed something other than labs and images and medications and barriers to discharge. It was invigorating.

Another strategy for maintaining a positive work-life balance is addition by subtraction. I did this more by accident and technological ignorance than by conscious choice. My hospital switched their email program from Gmail to Outlook this year, and when I put the new application on my phone, I didn’t know how to turn on the notifications, so I just didn’t. Since then, I only check my email once per day and rarely on the weekends. Checking my email on my own terms has been life changing. Although I’m not exactly “unplugged,” I feel unplugged. My attention is focused on the present. My pocket is not constantly pinging, and I don’t feel the pressure to always be available. This isn’t a new strategy, I know, but I always felt like I was somehow required to be immediately responsive as a physician, even when I wasn’t on call. I felt as if I was going to miss an opportunity or let someone down. In reality, the only thing I was missing was my own life.

In the last few months, as I’ve made these seemingly minor changes, I’ve noticed that I’ve felt more whole. I have realized that I’m not defined by my profession. I’ve felt more like me. I’ve also noticed that my interactions with others have been more meaningful and far less stressful. I’m able to apply myself to tasks in a more efficient way. This isn’t just a feeling I alone have; researchers at San Francisco State University looked into their own employees and found that those with creative outlets and hobbies outside of the workplace perform better and interact more positively with their colleagues (J Occup Organ Psychol 2014; 87:579).

It’s no secret; we are all busy. We all want for more hours in the day and to use those hours to be supportive and present for our patients, our residents, our students, our family, our loved ones, and our Labradoodles. Okay, maybe that last one is just me. The reality is that we can’t have more hours. We have 24 of them: no more, no less. How we choose to spend our hours makes all the difference. I am not advocating for you to spend less time devoted to providing the best care to your patients, and I know that means you will be put in a difficult position where you have to, again, give up something. I am advising that that “something” not be yourself. Cherish those things that make you you. Keep going to concerts, keep reading, keep writing, keep running, keep dancing, keep watching your kids’ cross country practices, keep playing chess. The person who was accepted into medical school and subsequently into residency was the entire you, the whole you, and that is the you who is the best at your job.

September 27th, 2017

Thoughts on Caring for Sexual-Minority Patients

David Herman, MD

David Herman, MD, is a 2017-18 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Southern California / LAC+USC Medicine Center in Los Angeles

According to recent polling, approximately 4% of the population of the U.S. identifies as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, which equates to more than 10 million people scattered from coast to coast. In truth, this number likely underestimates the true prevalence. Despite the progress that we have made as a nation towards LGB acceptance and equality, people who identify as LGB still experience discrimination and hate, such that many feel pressured to remain “in the closet.” Even those who do open that closet door often live in the daily reality that, in many ways, in many minds, and in many places, they remain second-class citizens.

I am one of them, a gay man who lives in West Hollywood, California. I count myself fortunate in that I have lived, worked, and studied among accepting individuals and in accepting institutions; aside from the adolescent and early adult struggles that I experienced prior to coming out — teasing and name-calling, feelings of inadequacy, fear of disappointing those around me, all of which are relatively common amongst my LGB peers — I have emerged relatively unscathed and now live a life in which I feel supported, and which gives me opportunities that I am thankful for on a daily basis.

Yet, I am reminded frequently that my sexual orientation classifies me as a vulnerable minority. The recent rescinding of protections for transgender military personnel (Note: my omission of transgender individuals prior to this is intentional, as I believe that the topic of transgender people and their healthcare deserves special attention: I will be addressing that in a future blog), the numerous attempts to pass “Religious Freedom” bills around the country, and the still deep wounds inflicted by the senseless tragedy in Orlando, Florida, for example, remind me that we still have far to go to achieve true equality, legally and beyond, and that we remain in many ways, the targets of a discriminatory society. I am further reminded of this when I read the news or watch the talking heads debate our rights on cable television — as though arguments to codify our status as second-class citizens are valid ones to be discussed and are not simply discriminatory statements. And all of these things are contributing factors in the overall poorer health of LGB youth compared with their heterosexual peers. Mental health, especially, is affected: studies have demonstrated significantly higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders, higher rates of depression, and a dramatically higher rate of suicide attempts and ideation amongst LGB people.So, as a gay man, I do the best I can to channel my feelings into promoting and expanding the health and welfare of my community. As a gay doctor, however, this strikes a different chord in me. It is not solely because of obvious health disparities that exist amongst members of the LGB community, although they are real and extensive and, many times, inadequately addressed in healthcare settings (NEJM JW Gen Med 2016 Aug 1 and JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176:1344). Higher rates of sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men (with the growing emergence of antibiotic-resistant organisms), dramatically lower rates of adherence to national guidelines for cervical cancer screening amongst lesbian women, higher rates of smoking and substance use and abuse amongst LGB people in general — these should be of concern to all physicians in Internal Medicine, especially as we shift more of our focus toward preventative care. The National LGBT Health Education Center, a program of the Fenway Institute, has a tremendous amount of resources to address some of these specific concerns, and I would challenge you to access their materials to educate both yourself and your peers and keep up to date on very pertinent issues that affect your LGB patients.

LGB Patients Sometimes Fear the Healthcare System

My fear is that those of us in the medical profession avoid many basic issues of sexuality and orientation. In 2003, for instance, a survey published in the Journal of Homosexuality revealed that 71% of medical residents did not regularly ask sexually active adolescents about sexual orientation; when pressed, 93% reported that this was because they were too uncomfortable to do so (J Homosex 2010; 57:730). In 2002, 6% of physicians surveyed by the Kaiser Family Foundation reported that they were uncomfortable treating gay or lesbian patients. Attitudes can change, of course, and these surveys were conducted over a decade ago. Yet, a recent publication in the American Journal of Public Health revealed that amongst 200,000 surveyed healthcare providers, including physicians, implicit preferences toward heterosexual patients over members of the LGB community existed among heterosexual providers (Am J Public Health 2015; 105:1831). This attitude (whether conscious or unconscious) further solidifies the already thick wall that exists around many LGB people, one built of distrust for the medical profession due to fear of judgment or discrimination and a history of both: It was not long ago that we doctors classified homosexuality as a mental disorder. And these fears are present even among our peers: A 2015 study in Academic Medicine concluded that sexual and gender minority medical students often conceal their identity during training (nearly 30% of such students), with nearly half of concealing students reporting fear of discrimination (Acad Med 2015; 90:634).

My fear is that those of us in the medical profession avoid many basic issues of sexuality and orientation. In 2003, for instance, a survey published in the Journal of Homosexuality revealed that 71% of medical residents did not regularly ask sexually active adolescents about sexual orientation; when pressed, 93% reported that this was because they were too uncomfortable to do so (J Homosex 2010; 57:730). In 2002, 6% of physicians surveyed by the Kaiser Family Foundation reported that they were uncomfortable treating gay or lesbian patients. Attitudes can change, of course, and these surveys were conducted over a decade ago. Yet, a recent publication in the American Journal of Public Health revealed that amongst 200,000 surveyed healthcare providers, including physicians, implicit preferences toward heterosexual patients over members of the LGB community existed among heterosexual providers (Am J Public Health 2015; 105:1831). This attitude (whether conscious or unconscious) further solidifies the already thick wall that exists around many LGB people, one built of distrust for the medical profession due to fear of judgment or discrimination and a history of both: It was not long ago that we doctors classified homosexuality as a mental disorder. And these fears are present even among our peers: A 2015 study in Academic Medicine concluded that sexual and gender minority medical students often conceal their identity during training (nearly 30% of such students), with nearly half of concealing students reporting fear of discrimination (Acad Med 2015; 90:634).

Clearly, we need to do better, for our patients and for ourselves. The first step in addressing the many health disparities that exist in the LGB community is to confront the issues that we, as a medical community, have with sexuality and orientation. That is where we, as residents, especially as residents in Internal Medicine, can take a special role. Residents are the next wave of attending physicians in community and academic centers across the nation, and we have the opportunity to re-create atmospheres that have traditionally been less than inviting to those with differing sexual orientations. Furthermore, as residents now, we are often the first ones to take full histories for our patients, the first one to see them in the ambulatory setting, and the ones that strategize with them to establish treatment or follow-up plans, which leads to continuity and building of lasting relationships. To do this well, we need to know our patients; and this includes understanding their sexual orientation and how it directly and indirectly affects aspects of their lives. I can recall the first time that my physician asked me about my sexual orientation; it changed our therapeutic relationship immediately as I felt a comfort level as of then unachieved, and allowed me to discuss issues openly and honestly to the betterment of my own health.

Caring for LGB Patients

So… what are some steps that we as medical professionals can take?

- Strive to create a welcoming, supportive environment in which to care for and learn from your patients.

- Focus on your attitude, demonstrate your willingness to work with others, and be open to the situations of your patients without the perception of judgment or preconceived notions.

- Get to know your patients outside of their medical complaints.

- Use inclusive language; avoid assuming someone’s sexual orientation or the gender of his or her partner, for instance.

- Make your line of questioning regarding sexuality and sexual orientation routine for all patients; this will normalize the discussion for you and your patients and will help to ease some of your discomfort as you continue to practice.

- Take a full sexual history of all your patients and understand the screening guidelines; many members of the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community require special consideration for screening for sexually transmitted infection, for instance, or special attention to substance abuse and mental health.

- Acknowledge your own discomfort or ignorance (if any) and work to move past it.

- Ask for clarification of words or topics that you do not understand; your patients will be happy to explain and this will give you an opportunity to not only learn about your LGB patients specifically but also to learn about them in general.

The LGB community is a strong one whose history is driven by resilience and survival. But that history has been marked by judgement, discrimination, and persecution, and that history affects each member of the community differently. It is important that we, as healthcare providers, respect this history and work to build strong and lasting relationships with our LGB patients. It is in this way that we can truly start to address the health disparities that this community experiences.

September 18th, 2017

Beast Mode Is Back! When Actions Speak Louder

John Junyoung Lee, MD

John Junyoung Lee, MD, is the 2017-18 Chief Medical Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Miami at Holy Cross, Fort Lauderdale, FL

Cal Football

I bleed blue and gold. No, I am not talking about Michigan, West Virginia, or Notre Dame. I am definitely not talking about UCLA Bruins (by the way, UCLA fans, a bruin is a brown bear). That’s right — I am a die-hard Cal Bears fan.

Thanks to Cal football, and particularly to legendary Marshawn Lynch, my college days were filled with excitement. (I am counting on you, Coach Wilcox.) Marshawn, an Oakland-native running back, is one of the best football players to graduate from Cal, and he happens to play for my team, the Oakland Raiders. Known for his power running style and ability to break tackles, he is one of the best running backs in the NFL, and I think he makes the world a better place. You think I am being dramatic? Let me prove you wrong:

- Marshawn blesses us with his famous unfiltered one liners. Sometimes he will grant an interview, but mainly so that he doesn’t get fined.

- Fam1st Family Foundation, which Marshawn helped to co-found with his relative, Josh Johnson (NFL QB), provides education and empowerment to underprivileged youth.

- Have you ever seen anyone better at “ghost riding the whip”?

- Marshawn Lynch sat down during the national anthem at Raiders preseason game against Arizona Cardinals. Judging by the national uproar that followed, actions still speak louder than words. Just ask Marshawn about it. Oh, wait — he might not answer your question.

Aug 12, 2017; Glendale, AZ, USA; Oakland Raiders running back Marshawn Lynch (24) prior to the game against the Arizona Cardinals at University of Phoenix Stadium. Credit: Matt Kartozian-USA TODAY Sports

Marshawn did not immediately elaborate on his action, but his sit-down happened in the wake of the violence at the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville and followed Colin Kaepernick’s protest against racial injustice and police brutality against people of color. Marshawn’s simple action, or inaction, polarized the football community and ultimately achieved its intended purpose: to sustain and stimulate conversation about what happened at Charlottesville and across the nation.

When pressed by the media about his anthem sit-down, Marshawn said, “So my take on it is, $#!t has to start somewhere, and if that was the starting point, I just hope people open up their eyes to see that there’s really a problem going on, and something needs to be done for it to stop. And if you’re really not racist then you won’t see what he’s doing as a threat to America, but just addressing a problem that we have.”

Racism

Individual and structural, overt and implicit — pervades every state and every industry, and medicine is not immune to it. While we doctors use objective measures, such as lab tests, to diagnose patients’ ailments, we also use heuristics in our medical decision-making, depending on our categorizations of people based on physical characteristics, such as race and ethnicity. And sometimes, a patient’s race becomes a confounder: A black patient’s pain is treated differently from a white patient’s pain.

The patients also bring their own biases and stereotypes to the hospital. A typical male Floridian octogenarian, meaning a white-haired transplant from New York or a ‘snow bird,’ presented to our emergency department for acute heart failure exacerbation. He was huffing and puffing until we put him on a noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation. Remarkably, between his gasps for his next breath, the patient managed to point at one of our residents of Middle Eastern heritage and to spurt out the following string of words: “I… Don’t Want… His Kind… Treating Me.” It was a paradigm of how not to start a vulnerable yet trusting relationship between a patient and a physician.

The story might seem to show an isolated incident, but our hospital has been getting such requests, with increasing frequency, in the past few months. Why? We are not sure, but we know that since the last presidential election in the U.S., there have been multiple reports of racist- and hate-fueled harassments and acts of intimidation around the country.

How Do We Fight Racism?

How do we approach such a sour situation in medicine?

Our duty as physicians is, first and foremost, to treat and to stabilize patients. Once patients are stable, those with competency have the right to refuse care under informed consent. In other words, patients can refuse care from unwanted physicians. In turn, physicians are also freed from our Hippocratic Oath to “consider for the benefit of my patient and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous.” It would be deleterious and mischievous to force a professional relationship that was built on bigotry.

While letting patients choose physicians based on race, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation seems like allowing hate to win, stepping away from the ‘fire’ helps physicians to protect themselves from unwarranted verbal assaults and constant emotional abuse. Physicians are allowed to acknowledge their human emotions, too.

We must perform our duties as physicians, but we do not have to tolerate hate. I recommend physicians to remove themselves from hurtful encounters, but I also encourage physicians to advocate for, or at least try to understand, someone from a different background. Unfamiliar does not have to equal uncomfortable: See it as a learning opportunity. After this blog, I might even become the recipient of racially charged comments. I am, however, willing to embrace whatever comments are directed at me. Why? Because that’s exactly what this is about: to break bread and generate conversations as a way to break barriers and hate. And besides, I could not turn down an opportunity to write about Beast Mode in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Go Bears!

p.s. Marshawn, holla back at your boy! Maybe when Raiders come to play Miami Dolphins in November?

August 29th, 2017

Procedures in Residency

Karmen Wielunski, DO

Karmen Wielunski, DO, is a 2017-18 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee

Hi. My name is Karmen, and I’m a fainter. It’s true. I am one of those people who occasionally falls victim (pun intended) to vasovagal syncope at its finest. It tends to happen at inopportune times and places. For example, the first time I passed out, I landed in a Christmas tree. I was in high school and suffering from a nasty viral illness, so I attributed the experience to volume depletion and moved on. However, shortly after starting clinical rotations in medical school, the Christmas tree incident came back to haunt me. Only this time, it was clear that clinical procedures were the culprit.

I quickly learned that some part of my brain has an aversion to blood – especially squirting blood – and it deals with this aversion by inducing syncopal events. This made for awkward experiences in operating and delivery rooms throughout medical school. It was frustrating, to say the least. People were understanding, but I still found myself avoiding certain situations in attempt to make as few “scenes” as possible.

Pre-Procedure Service Elective

When I started Internal Medicine residency, I was nervous. I knew my chosen career would keep me far away from operating rooms. But, I also knew I would be expected to learn how to perform certain procedures. In my mind, procedures meant blood, and blood meant syncope. I spent the first few months of my intern year contemplating how I was going to approach this issue. Eventually, I came up with the deeply insightful solution of “Maybe residency will be different!” So, I forged ahead.

Well, it turns out residency wasn’t different. The first sight of pulsating blood during my first arterial line attempt sent me straight to the floor. Luckily my senior was there to step in for me. I continued to attempt central and arterial lines during my months in the ICU, but I never felt confident. I knew I would always require someone with me for the times that my brain reminded me of its distaste for what I was doing.

In a final effort to prove to myself that procedures simply didn’t suit me, I requested to rotate on our hospital’s procedure service elective. This is a service comprised of an attending and a resident who spend all day performing bedside procedures – mostly paracenteses, thoracenteses, and lumbar punctures. Residents love the rotation because the volume of procedures allows for excellent learning by repetition. It is also a great way to learn ultrasound skills, because all of the procedures are done with ultrasound guidance. Patients and various specialties also love this service because it is an avenue for these procedures to be done at the bedside in a timely manner.

Procedure Service Elective

On my first day on the service, we had 2 lumbar punctures planned for the morning. My attending said he would do the first one and go over every step with me and that I could try the next one. When we got started – I honed in on my osteopathic education and fairly easily located the appropriate disk spaces. My attending agreed with my findings and then showed me how to identify the intervertebral spaces and spinous processes with the ultrasound. He then went through each step of the lumbar puncture procedure. When he inserted the small needle into the patient’s back, a quick rush of panic came over me. “Please don’t faint, please don’t faint, please don’t faint.” Moments later, he pointed out the return of clear spinal fluid. I was intrigued, and I was still conscious! He systematically walked me through the remainder of the procedure. Before I knew it, we were moving onto the next patient. It was my turn.

As I greeted the next patient and started setting up, I focused on being as methodical as my attending. I appropriately positioned the patient, located the disk space and confirmed with ultrasound. With the kit open and sterile gloves on, I fumbled through opening the lidocaine and drawing it up. My attending systematically walked me through the steps, and before I knew it, I was ready. I advanced the lidocaine needle a little at a time, fully expecting to encounter bone and have to try again. But, the needle kept going, and I successfully anesthetized the patient on my first try. When it came time to advance the lumbar puncture needle, this also came more naturally to me than I expected. I slowly advance the needle and intermittently checked for clear fluid return. On the third check, there it was! Success! And, again, I was still conscious!

Post-Procedure Service Elective

By the end of the month-long rotation, I completed over 30 bedside procedures with zero syncopal events. I hadn’t really thought about the fact that not all procedures have a frequent squirting blood component; it turns out my brain has no aversion to clear-ish body fluids, and without the passing out component, I actually really enjoyed doing procedures. In 4 short weeks, I acquired a newfound confidence and a very useful set of skills. In retrospect, that was easily my favorite month of residency.

During the remainder of my time in residency, I experienced a sense of pride in my ability to perform these bedside procedures as well as teach other residents how to do them. This past week, during my first block as an attending physician, I was able to guide one of my interns through performing his first paracentesis using ultrasound guidance. He did very well. Afterwards, we discussed how empowering it is to be able to literally take the care of a patient into your own hands rather than relying on someone else to do it for you. I feel lucky to have trained at a place that houses such a great procedure service. It gave me confidence in an aspect of medicine that I didn’t think was possible for me. It also very much molded the way I will practice and teach medicine in the future.

August 23rd, 2017

Is Transferring a Patient to the ICU a Failure?

Cassie Shaw, MD

Cassie Shaw, MD, is a 2017-18 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Saint Louis University Hospital in Saint Louis, MO

As I sit with one hand wrapped around a greasy diner cheeseburger, eating my feelings — I mean, my dinner — it sure feels like failure. It’s 7:22 pm, and the first patient with my name listed as the attending is being packed up to roll into his new room in the intensive care unit. Did I mention it’s my first week on service? Okay, so I’m probably being dramatic, because the patient, although very ill, is only going to the ICU because he needs closer monitoring for the next 24 hours. However, this was my exact biggest fear as I began attending. In the scenario that plays out in my head, it’s a missed diagnosis that is obvious to everyone else; the patient has decompensated due to my mismanagement, a rapid response has been called, and I hang my head in shame while my patient is urgently transferred for higher care. I know I’m not alone in this fear. As I reflect on this feeling, I have to ask myself several “why” questions:

The first “why” is “Why is it so hard to give up the care of a patient to another physician?” ICUs are designed for taking care of patients that are too sick, too needy, too unstable for the floor. Even in a closed ICU, those physicians are our colleagues. I’m currently practicing at the hospital that houses my residency, so the residents who will be taking care of my patient are physicians that I worked beside for years. I know them, I trust them. Further, the ICU attendings are physicians that helped educate me for the last 3 years. I know them too, I trust them too. Is it pride that ties us so tightly to our patients, then? Maybe. But more so, I think we simply want to be *the one*. We want to be the one who gets the satisfaction of making a diagnosis, we want to be the one to help the patient. It’s satisfying work, and it’s why I chose Internal Medicine, where I get to be the primary team; the team that gets to be the one. However, it’s important to remember caring for a patient never takes place in a bubble. It requires teams of nurses, social workers, care partners, custodians, kitchen staff, pharmacists, therapists. I readily accept the assistance of those individuals on every patient, and I need to learn to more easily accept the assistance of my colleagues without feeling like I’m going to lose that “the one” high.

This buttery, garlic steak and heart of brie were not Band-Aids for worrying about a patient, but they will work to calm fears.

The next “why” is “Why am I worried about having to use the ICU?” Well, as I implied earlier, I think this is a projection of my fears that I might a bad physician. In medicine, we are used to constant, out-loud comparisons to one another: test scores, mid-rounds pimp questions in front of our team mates, even our notes outlining our thought processes are up for judgement by colleagues. In fact, just tonight, I wrote an addition to my residents’ transfer note to further explain why I had broadened antibiotics — because I knew my management would be scrutinized by the ICU team. Although stressful, and driving my diet into the ground, I think this fear can be beneficial when used wisely. Cheesy as it sounds, this fear forces me to double and triple think my decisions. The mismanagement scenario was definitely playing through my head as I ordered the chest CT, sealing his fate to move to the ICU. Without that fear would I be as careful? Would I be as thorough? Would I be as thoughtful? As I write this, it’s occurring to me that maybe this “fear” isn’t lack of confidence; it’s care for the patient’s outcome.

St. Louis style ribs from Pappy’s and Urban Chestnut craft beer work for both celebration and guilt. No excuse needed.

Going forward, I have no doubt I will have patients whose diagnoses I will miss. They will unexpectedly decompensate, and they will end up in the ICU. When it happens, I’m going to get my physician high from knowing that I helped the patients get to the level of care they required. Until then, I have to remind myself that my nervous, churning stomach that can only be quieted with high-calorie comfort food is, in fact, a surrogate marker for me wanting to do right by the patient. Well, that, or a peptic ulcer.

June 27th, 2017

Four-Oh-Wonk. The Reboot.

April Edwards, MD

April Edwards, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident for Internal Medicine/Pediatrics program at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

At the beginning of the year, I wrote about the rude awakening I was experiencing with regard to my own finances. I heard from more than a few other imminent or recent resident graduates who expressed some degree of similar feelings of being inadequately prepared in the financial realm.

At the risk of being incredibly rudimentary, I thought now was as good a time as any to try to share a few small lessons and gems of information I have been gleaning during the past year. I am finally trying to take an active role in my finances rather than continuing to bounce from paycheck to paycheck, still naively thinking that “Financial Literacy” was something I’d “get around to later.”

Disclaimers:

- I probably represent a rather extreme version of financial ignorance, and I suspect that most residents likely are a bit better versed in some or many of these basics. But this is targeted at others who might still be lacking financial savvy. In no way do I think this is the “right” way or only way to start trying to boost one’s financial IQ, but I wanted to offer it up as a way for people to at least get started.

- Almost all of what I am going to write comes from a book I happened upon that knocked the rose-colored glasses right off my face, “I Will Teach You to Be Rich,” by Rhamit Sethi. I have absolutely no ties to the author, and I will get exactly no props or cash money for talking about it, as he has no idea who I am or that I have read his book. But I did find the book (despite the title, which I initially found a bit off-putting) to be a FANTASTIC financial primer for typical resident aged/minded folks. (I may or may not have found it when Googling “finances for dummies”…)

So here are a few of my thoughts — if you find any of them useful, amazing! If not — totally fine, too. I just want to keep re-circulating this topic into the general conversation for residents. And, I’ll probably sit on my porch in a rocking chair looking at the shiny fresh new resident Whippersnappers who are about to start their career, wave my cane, and say “Don’t be like me! Learn from my mistakes!”

Ok. Here goes.

1. Download Mint (www.mint.com)

Or something like it. Mint is an app/website that will let you track every single (cash or non-cash) penny that you spend. You input your various bank/credit/debit card/savings accounts, and then it shows them to you ALL IN ONE PLACE. Which is amazing. Because this is probably a good place for financial novices to start — take inventory. How much money do you have? How much do you owe and to whom? I’m sure many Attendings used to do this sort of thing with an Excel chart or even by hand, which is also totally fine, if that is your style. The point is, take inventory. Do it now.

2. Look at where your money is going

Now that you have all of your financial info in one spot, look at what you are actually doing with that money. Mint (and Mint-like apps) makes it simple, because it automatically labels each of your transactions and keeps track of each category. Then, it provides nice visuals, like a pie chart that shows you what proportion of your money you are spending on, say, Travel versus Eating Out. It’s a nice way to catch things you probably don’t think about regularly — like the various monthly subscriptions you bought for Netflix/Hulu/Spotify, since those usually autodraft (and, out of sight, out of mind, right?) You can play with the categories as much as you want to make them make sense for you — for example, I have a category labeled “Colby” for pet-related expenses for the world’s greatest dog, Steven. T. Colbert Edwards. An expensive booger.

3. Determine fixed vs. flexible costs

From the inventory you made (of the things on which you are spending money), figure out which of those are true fixed costs — i.e., they are monthly or weekly “must pays.”  These generally consist of things like rent, utilities, cell phone, groceries, pharmacy, gas, car insurance, and debt/loan payments. Plus any of those recurring monthly subscriptions. Go back several months to look at the average cost for each of those, and write them down. Then look at “everything else,” which are your flexible expenses: Eating out. Trips. Gifts. And all your myriad one-time and unplanned expenses: License renewal fees, Board registrations, QBanks, interview hotels/rental cars, parking tickets. (FYI, I could write an entire other post on all of the hidden costs of finishing residency — Turns out that it costs a lot to graduate into being a real doctor.) Anyway, now zoom out. Is that what you thought you were spending on that stuff? In my case, I was spending way more than I realized, just not by really paying attention to where my money was going each month.

These generally consist of things like rent, utilities, cell phone, groceries, pharmacy, gas, car insurance, and debt/loan payments. Plus any of those recurring monthly subscriptions. Go back several months to look at the average cost for each of those, and write them down. Then look at “everything else,” which are your flexible expenses: Eating out. Trips. Gifts. And all your myriad one-time and unplanned expenses: License renewal fees, Board registrations, QBanks, interview hotels/rental cars, parking tickets. (FYI, I could write an entire other post on all of the hidden costs of finishing residency — Turns out that it costs a lot to graduate into being a real doctor.) Anyway, now zoom out. Is that what you thought you were spending on that stuff? In my case, I was spending way more than I realized, just not by really paying attention to where my money was going each month.

4. Make a conscious spending plan

Now that you know where your money went when you weren’t watching it particularly closely, you can turn the tables (on yourself), take the Code Team Leader lanyard, and start being the one calling the shots. Use the data you collected to actually plan how you want to spend your money. You already know the monthly amount of your incredibly exorbitant resident salary, and you know the unavoidable/fixed costs you have each month. Some general thoughts about how you should divvy up your money. Some “experts” suggest that, generalishly, your categories should look like this: All of your fixed costs together, ≈60%; savings, ≈10%; retirement and other investments, ≈10%; guilt-free spending, ≈20%. Again, this is a rule of thumb and, in this particular case, my thumb ala Ramit Sethi. But you get the general idea. Also, quick word(s) about those groups:

- Fixed Costs (60%): Get rid of the stuff you don’t actually need to be eating into your money. Never watch Hulu? Cancel it. Have a subscription to a medical journal you always pretend you are going to read, and never do? Cancel it. (Plus, your university/hospital probably allows you to access most of the big name medical journals, so you can still read them if you want.) Make sure you’re only paying as much as you need to for stuff like your cell phone bill (downgrade to a lower-cost plan if you don’t need “unlimited minutes and messages”) or your cable bill. Seriously, call up the companies and ask them to slim you down to a plan/package that “fits” your usage.

- Savings (10%): This one is hard, but try to have some. Some big-ticket items will require residents to have extra money around at some point — a wedding, a car, a baby or three, a down payment on a house. We probably all envision ourselves spending a good chunk of money on one or more of those things “later,” but it makes a lot of sense to put some money in those pots, so there is something from which to actually draw on when it gets to be “later.” Also, another less sexy category that you need to fund is “emergency/rainy day account”. (Or, more likely, lost job+got injured+unforseen repairs needed+rain). The rain alone you could probably deal with. You know, because, umbrellas.

- Retirement/Investment (10%): Your hospital has some sort of retirement account that you should ask the GME about, so you can fill out the (generally single-page) form to get started. This is the 401k, 403b, 457b stuff. It’s alphabet soup — but it’s worth Googling to understand. Basically, start saving for retirement now, if you haven’t already. Most hospitals will help you out by automatically funneling some of your salary (as long as it follows their guidelines/contribution rules) directly into a retirement account associated with the above alphabet soup. And this happens before you ever see that money. Which means it is a whole lot easier not to miss it — because it was never part of what you were taking home in the first place. Huge psychological win. And if you want to be super fancy, you can also have your own (not necessarily work-affiliated) investment/retirement accounts. Like an IRA or Roth IRA. Turns out that if you put money in investment accounts, instead of under your bed (or even in one of the super low-yield savings accounts that most of us have), it will probably grow over time. Which is why people recommend investing. Giving investment advice is way beyond my pay grade, but learning at least a little about it is worthwhile. Investment managers make essentially the equivalent of a nicely arranged manila folder with the right balance of individual investment-colored papers in it — called index funds. They are pre-mixed investment portfolios for people like me who do not know how to build a “well diversified portfolio.”

- Guilt Free Spending (20%): The point of this category is that, if you have done a good job at knowing how much you are going to be spending on fixed costs, then whatever money you have left over each month you can spend with a relatively clear conscience. You don’t have to worry that you’ll default on your credit card payment or won’t be able to make rent, because you already set aside that money. This is where eating out, travel, gifts, and concerts come in. No one wants residents to be any more burned out that they already are. So, with a little work on the front end, you can feel relatively assured that you can truly use the left-over bit for things/hobbies/extras that are important to you.

5. Make your credit score sexier

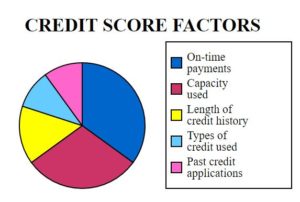

Credit scores matter a whole lot going forward. They are basically the financial health equivalent of a Medical Record FaceSheet. It’s a snapshot look at your financial “health.” How good are you with money? People who you will need to lend you money (banks, credit cards issuers, car salesmen, mortgage brokers) want to know how risky of a move it is to trust you. In this realm, instead of looking at medication adherence, health maintenance screening, and number of chronic medical conditions, lenders look at several dimensions of your financial health. The basic components are:

- What is the balance of credit/other people’s money that you owe vs. how much you have available to you/been approved for (credit utilization rate)?

- For the money you already owe, how good are you at paying on time?

- How long have you been at this whole borrowing money business (i.e., length of credit accounts, old vs. new credit)?

- How varied are your credit types? (Better to have your risk spread around in different types of credit — credit cards, student or car loans, mortgages — than all in one type.)

You want your score to be basically as high as you can get it, because this means you look “healthier” to potential lenders, and they are more willing to offer you credit, without making you pay through the nose. Many banks and credit cards have programs that will keep tabs on your credit score month to month (so does Mint), which can be useful. Scores range from 300 – 850. Above 700 would be a good goal. But how?

- The non-sexy answers are: Be a good steward of your credit. Pay your bills on time. Don’t willy-nilly accept credit card offers for which you’re “pre-approved,” just because you got them in the mail, or because you saw a funny commercial with Alec Baldwin. Don’t borrow more than you need (and, hopefully, you have a good idea of what you actually need, based on the steps above).

- One quick move you can try that actually helps is to ask for an increase in your credit limit on your current credit cards. As mentioned above, part of calculating your credit score is your credit utilization percentage (amount used/total available or offered). So, harkening back to the days when we did actual math — increasing the denominator will make the overall percentage amount lower. You can literally call up your credit card company and say something to the effect of “Hi there, I’ve been a loyal customer for X years, I pay my bills on time, and I would like to request a credit line increase.” As long as you have been pretty reasonable with your accounts, they will often just do this for you on the spot! One of my cards tripled my limit during a 5-minute phone call. **Important: The point of doing this is to make you owe a lower percentage. It is NOT for you to spend more! That will literally defeat the purpose and shoot you in the foot.

6. Automate good decisions

Now that you have a basic background on how you have been spending your money and how you want to be spending your money, set it up so it happens automatically each month without you having to think about it! Get direct deposit for your paycheck. Then, link your checking, savings, and retirement accounts so that money is taken from your now replete checking account and neatly and automatically distributed into the other “pots,” loosely based on the allocation suggested above. This way, it happens without you having to remember or choose to do it each month. It will help you be fiscally responsible while you sleep (or more realistically, while you are on call)!

Phew. That was a lot. Bottom line, take a look at what your current spending is like on a granular level. Then decide what is important and what you need to be spending and saving. Set up your system to make that happen automatically so it doesn’t have to be another check-box at the end of each month. Be smart about credit, pay your bills on time, and push your credit score as high as you can get it.

I hope this was helpful to at least a few residents. Perhaps, like me, you didn’t get a solid background in this stuff earlier on, for whatever reason. It’s not the only way to think about finances, but it helped me, and I want to pay it forward. I know you guys are busy. Pouring your hearts and minds into doing good work. Keep it up. If no one has told you already this week, Thank You for what you do. Hopefully this can fall into the realm of “self care” and will help you build a solid foundation going forward.

Be well.

May 31st, 2017

What I Love About My Medical Students

Kashif Shaikh, MD

Kashif Shaikh, MD, is the 2016-17 Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine.

We all start with medical school

I still remember the day I got the welcome letter from my medical school. I was super excited and proud. My dreams of becoming a physician were now a reality. So, I pushed myself during my two basic science years and awaited my clinical years.

I bought my first stethoscope and white coat in anticipation of my third year. (By the way, I still have the stethoscope that I bought almost 15 years ago, and it is the only stethoscope I still use.) I started my first rotation in community health sciences and family medicine. I was thrilled! But, the first patient I saw described his chief complaint in a most interesting way. My patient said, “I have a gas that starts in my stomach and goes into my head.” Even though I have been practicing history-taking for some time, it took me a moment to collect myself and to complete that medical history. Anyway, things got better with time. Nothing beats being a third year senior medical student in a white coat with a stethoscope hanging around your neck.

I began my medicine clerkship. By that time, I could take a comprehensive history and physical without losing a beat. I started interacting more with residents and attendings. I wanted to be a teacher, and I started identifying role models.During medical school, I knew what kind of resident I wanted to be. I wanted to develop the same virtues that I admired in my role models: Kindness, passion, and dedication to teaching, and supportive and encouraging when the medical education process became very stressful. I wanted to be my students’ biggest support in a nurturing environment. I wanted to make learning fun, easy, and enjoyable. And I wanted to guide them through all phases of learning, from the medicine wards to residency applications.

By U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Gary Granger Jr. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

A plan for teaching medical students

As an attending and a chief resident, I have been applying some of the key concepts about teaching medical students that I learned at the APDIM chief resident meeting.

- 1. I start orienting medical students on day 1. I discuss learning objectives, expectations, and how they can get the most out of their internal medicine rotations. I explain the residency match process in detail. I guide them on how to get LORs and write personal statements.

- 2. We do 1-hour teaching sessions, three times weekly. Each student gives a 10-minute presentation (2 students per session) to learn how to present and to become teachers — as residents and attendings, I hope they will carry on this tradition. They receive feedback and some clinical pearls, and we work on board questions with explanations and test-taking skills and strategies.

- 3. To help develop clinical reasoning, we have a student-style morning report session. We simulate an actual patient scenario. I ask them to take a history and to tell me what they would do on the physical exam to come up with a differential diagnosis. Then I ask them to narrow it down, based on labs and imaging they would order.

- 4. I assign new patients to a medical student and an intern. The patient sees the student first, followed by the intern. We all sit down and critique the student’s presentation of the case. Then I round with them to do bedside teaching. Our team comes up with a consolidated plan for the next day’s rounds. With this teaching method, students begin to master clinical reasoning.

The best part of being an educator

I hear a lot of people complain about medical students. Do teachers and educators take responsibility for orienting them and teaching them? Patient care can be time-consuming, but students need direction. What’s the point of being on a rotation if no one is teaching? We have all been students. Engaging students more, and emphasizing how important they are as team members, makes a huge difference.

I am amazed by medical students’ learning potential. They just need a little motivation to get things moving. I ask these students to be the future educators and be role models for their future students. Students learn best when they are given constructive and objective feedback through examples.I am very proud of my medical students. They are my responsibility when they are rotating with us, and they should get maximum education out of the rotation. I dedicate this blog to all the medical students who are our future educators and physicians. Make us proud. Work hard, and don’t let anyone discourage you. There is a reason why you were selected for medical school. Best wishes and good luck to everyone in their future goals.

-

- “What the caterpillar calls the end of the world, the Master calls a butterfly.” – Richard Bach

May 16th, 2017

Constructive Criticism

Joseph Cooper, MD

Joseph Cooper, MD, is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania.

Here are some questions that are still on my mind as I approach the tail end of my chief year. I’m thinking about the best ways to offer constructive feedback.

- What is the best way to approach a struggling learner?

- What is the best way to give guidance and feedback without being perceived as a tyrant or overbearing?

- How can I maximize the potential of my team members and the trainees with whom I work, based on performance evaluations?

A senior colleague surely did not lie when he told me that his year as chief resident was “one of the best years of my life.” Our institute might be unique — I have an unrestricted medical license, I function as a teaching hospitalist for 11 weeks of the year, and I precept in the outpatient general internal medicine clinic 1 day each week teaching residents. So, I might have the perfect transition from resident to “junior attending.” But these activities come in addition to the teaching responsibilities, leading of daily morning reports, troubleshooting, and being the mediator between the residency administration and the residents that are the essence of being a chief.

I think about the great mentors I’ve had throughout my training, and I try to emulate the feedback given to me (whether direct or indirect) when I interact with the learners under my tutelage. But during my short time as a “junior attending,” this year, the above plan is a lot easier said than done.

The trick is to emulate mentors who thought about the 3 questions at the top of this post, and NOT to fall into the trap of saying what trainees want to hear. For example, I remember feedback sessions with attendings who would say: “You’re great, you’ve done everything right, only thing to improve is that you should read more.” Read more? Read more? I always got a bit upset by this, because we all should read more. Medicine is life-long learning, for medical students coming out of basic science to the seasoned triple-boarded subspecialist/physician scientist. So again, back to the original questions at the beginning of this entry. How do clinician educators and mentors provide actual “constructive criticism,” that is appropriate, non-threatening, and useful in the future?

I’m by no means an authority on the matter, but here are some helpful hints on that seem to have worked well this year:

- Set the stage: Provide clear expectations. Sometimes this requires going the extra mile and providing a written document rather than verbally setting expectations at the beginning of a rotation/week on service. I have drafted my own “expectations,” that I email to all learners prior to coming on service. This step is key to providing useful feedback at the end of a rotation, because the learner can’t say “well, I didn’t know I was supposed to do XYZ.” Setting the stage also applies to the environment in which feedback is given: in a timely manner, and one that is private, protected, and confidential.

- Ask open-ended questions: You can never go wrong with this. With patients or with learners. This is a skill most of us accept as important, but often fail to use correctly. Beginning a feedback session by allowing the learner to self-reflect on his or her successes will usually allow for an easier transition to discussion of areas where the learner needs improvement. A simple introduction such as: “So, what did you think of the past week?” is non-threatening, open-ended, and allows the learner to start and (importantly) control the dialogue.

- Use the “sandwich” technique: This is only a bit different from the infamous “breaking bad news,” dialogue, but the sandwich technique is an effective way to deliver constructive feedback and promote change in the skills and behavior of the learner. To use the sandwich technique, first reinforce and give positive feedback on skills and behaviors that you directly observed. This fosters confidence in the learner, promotes positive reinforcement, and usually encourages the learner to seek feedback from others. After this step, ask the learner to identify deficiencies and areas in which he or she thinks improvement is needed. If the learner has already identified areas that need improvement (in the open-ended dialogue in step 2 above), you already taken the first step. Provide them with specific examples on how they can improve and in the behavior/skills that you directly observed that could be refined. When giving positive feedback, it is best delivered immediately, while “on the spot.” When giving constructive feedback, I’ve found it best to keep a log, and review situations at a formal feedback session near the end of the learning experience.

- Seek confirmation and end with a plan: The goal of a constructive feedback session is to be non-confrontational and to give the learner tools and skills to facilitate change. At times, these sessions may be emotionally charged, and the learner may take the feedback personally and feel “singled out.” Following steps 1-3 above will help avoid this angst. Finally, have the learner make an action plan before leaving the session. (E.g., exactly how to approach a patient and care plan.) Have the learner give you their summative assessment and then facilitate and form an action plan for moving forward.

Educators should continue solicit guidance from mentors and institutional leaders about how they provide constructive feedback to learners. Lastly, the educator should always solicit feedback from their learners, confirm constructive feedback, and have an action plan to improve deficiencies.

On that note, I will leave you with a“throwback” New York City photo, in preparation for my return to the “big apple.”