An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

August 6th, 2017

Have We Reached the End of HCV Drug Development?

Two new HCV regimens gained FDA approval recently, bringing us closer to the end of this extraordinary phase of drug development.

Think about it — has there ever been a more spectacularly rapid improvement in treatment of anything? If so, please let me know what that is. Remember, as recently as early 2013, highly toxic interferon-based therapy (with ribavirin and telaprevir or boceprevir) was still standard-of-care.

The recent approvals: Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir (Vosevi) on July 18, indicated for patients who have failed prior treatment with either sofosbuvir or an NS5A inhibitor. Twelve weeks of treatment (one pill daily) will cure 95–96% of patients, and pretreatment presence of NS5A, NS3, or NS5B resistance mutations does not reduce response. A month of sof-vel-vox — which will only be used as a salvage therapy — is priced at $24,900.

Then, glecaprevir-pibrentasvir (Mavyret) was approved on August 3rd. A pan-genotypic regimen that includes both an HCV protease inhibitor and an NS5A inhibitor, “G/P” is 3 pills daily, requiring only 8 weeks of therapy in treatment-naive individuals without cirrhosis. Clinical trial results show cure rates in the high 90s, with a low incidence of treatment-related adverse events requiring drug cessation.

Glecaprevir-pibrentasvir can also be used in patients with renal  impairment (including dialysis), prior treatment failure of genotype 1 with either an NS5A inhibitor or PI (but not both), and in compensated cirrhosis. Treatment duration should be increased to 12 weeks in those with prior treatment or cirrhosis.

impairment (including dialysis), prior treatment failure of genotype 1 with either an NS5A inhibitor or PI (but not both), and in compensated cirrhosis. Treatment duration should be increased to 12 weeks in those with prior treatment or cirrhosis.

So where does that leave us in terms of “unmet needs” in HCV therapy?

Let’s review what we currently have:

- Nearly 100% of those who get treated are cured.

- Most regimens are one pill daily.

- Ribavirin is rarely required for treatment-naive patients.

- Side effects leading to drug discontinuation are exceedingly uncommon.

- Treatment duration is only 8–12 weeks.

- Drug interactions are mostly manageable; if not, HCV treatment is so short that temporary discontinuation of the conflicting drug is usually fine.

- Several pan-genotypic options are available.

- Certain therapies are also effective for treatment-experienced patients with resistance.

- Some regimens are safe and effective for those with moderate-severe renal disease — even hemodialysis.

From a medical perspective, this doesn’t leave out a whole lot, does it? Treatment of HCV is so easy there’s a strong push in some circles to move it to front-line providers in primary care — and of course outcomes in their hands are as good as with hepatologists and ID specialists.

Yes, cost of and access to HCV therapy remains an issue, especially in certain regions.

But things have vastly improved in this area too. With prices way down from the crazy days of early 2014 (when the non-FDA approved “sim-sof” regimen was > $100,000/cure), we should anticipate that more payers will stop medically unjustified policies such as fibrosis criteria, negative toxicology screens, and limiting prescribing of HCV therapy to specialists.

And market forces are doing something — note that the wholesale price of G/P is $13,200 per month, very close to the negotiated discounted price for LDV/SOF with the VA and certain state Medicaid programs.

Which brings me back to the title of this post — Have We Reached the End of HCV Drug Development?

If we’re not there yet, we’re certainly close.

Here’s a poll about where we should go with HCV research — please vote!

Save

I was torn between the vaccine and implementation. I chose the vaccine because that does seem like the biggest challenge, from a science standpoint at least. But getting HCV treatment to those that need it is so critical and so filled with obstacles (including the insurance obstacles you mentioned, Paul). When I lecture on HCV, I show my students the graphic in this article: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/22/5/15-1980_article to remind them that we still have a long way to go to get treatment for everyone with HCV. (And now I can’t remember if I got that link from you, Paul. If I did, thank you!)

Thanks Dr Sax-always interesting and informative. I’m in rural primary care. I’ve treated a couple dozen people since early 2016 as part of an ECHO program. Both my treatment failures to date have been in CPT B-C patients. Treatment options for such decompensated cirrhosis treatment failures remain limited, esp for GT3, as we can’t use protease inhibitors. This might be a small group of patients but it seems an unmet challenge.

Hi Tom, agree these are very tough patients to treat. Assume you have access to resistance testing, and they would are not VEL/SOF + RBV candidates? And of course even if HCV were curable, those with advanced fibrosis still have substantial underlying risk for liver decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma. But that’s a different research question!

Paul

There still is the unmet need as mentioned above for those that fail an Ns5a regime.

Some of the resistance mutations apparently are somewhat more resistant than others,hence there not being 100% success .

This particular sub-set of treatment failures do not currently have anything on the horizen

Thank you much Dr Sax and Rod. He did 12 weeks of SOF/VEL/Riba. He was NS5A RAS neg before treatment but now has a Y93.

There was a break in treatment which I’d imagine contributed to development of resistance: patient didn’t do what CVS Caremark required of him to get refills and they cancelled authorization at end of 4 weeks so then we got auth for another 12 weeks and I believe he was adherent, and tolerated ribavirin well. I have discussed the case with hepatologists who mentor us in ECHO program and feeling is that 24 weeks of same regimen is the only real option, if the insurance company will approve. I understand the SVR rate is quite good, but patient hasn’t decided whether to pursue this route or not.

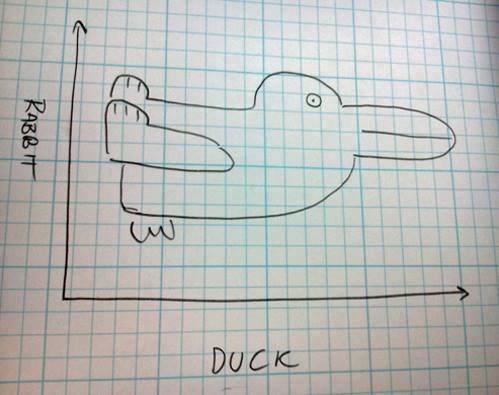

Also, that’s a duck. The common goldeneye.

the cost of “G/P”:

Abbvie, based in North Chicago, Illinois, said Mavyret’s list price without insurance will be $26,400 for eight weeks’ treatment, $39,600 for 12 weeks’ treatment and $52,800 for 16 weeks’ treatment.

That’s some price difference compared to competitors!

As always, enlightening assessment of the hep C world.

The amazing thing about these “list prices” is that they sometime bear little relationship to what the drugs cost our patients — meaning that the payers, pharmacy benefit managers, and drug companies have negotiated something quite different! As noted above, the price of 8 weeks of treatment for G/P is very similar to what Massachusetts Medicaid is currently spending on LDV/SOF. Let’s see what happens with the next round of negotiations.

Paul