November 7th, 2019

Painting in a Visual (Abstract) Medium

Justin Davis, MBBS

I’m not creative. I wish I were. I listen to music (with my particular choices being classical and music from video games) and wonder to myself how people are able to come up with such amazing pieces of art and media. I’ve tried it myself. I used to play piano back in med school, before the constant house moving and having to pay to get the piano moved separately and tuned each time made it non-financially viable (my old piano is elsewhere now, and my current time is taken up by way too many non-creative things to realistically pick it back up). I tried to create music, tried to rack my brains to come up with something. But my brains just won’t rack, not in that way. In a similar fashion, I don’t learn in a visual manner. I’ve seen people draw beautiful flow charts and mind maps while they were studying, but mine are simply walls of text with nary a colour, paragraph, or picture in there. It’s just how I work.

Which brings me to today’s topic and why I find it rather fascinating that use of the visual abstract is increasing in social media to create engagement as well as to disseminate scientific information. If you haven’t heard of visual abstracts, it might be because they are a relatively new thing — only a mere 3 years old. They were first coined by a clever chap by the name of Andrew Ibrahim who showed that use of these constructs on social media platforms increased engagement with the post compared with a simple text-based design, despite them carrying essentially the same information. (Regular readers of my blog posts may have noticed there’s a social media theme here once again. In my earlier discussion of the Nephrology Social Media Collective (NSMC) and the fantastic work they do promoting free online medical education through social media, I failed to mention that the NSMC has strongly taken up use of visual abstracts and are actively teaching others how to make them.)

When you stop to think about it, why wouldn’t visual presentations be better? How many of us have stood there, bored in a line, waiting for coffee or public transport or whatever it might be, and scrolling through Instagram or Reddit? These platforms are visual places. Things catch your eye, and you stop to read more about them. It’s so much easier to blithely scroll past several posts that are just blocks of text than it is to pass something that is colourful, creative, and (especially in our case) conveying important results of the study in an easily digestible fashion. A social media platform can be used for some amazing online education, but it is the same platform that can be shallow and cause your personal presentation to be easily missed if it’s simply conveyed in text. And we wouldn’t want that, now would we?

This way of disseminating information is becoming increasingly common. You may have noticed The New England Journal of Medicine, for example, doing just that. A quick perusal of NEJM’s twitter feed reveals several visual abstracts pertaining to some recent articles, such as the article about transcatheter aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients, to pick one example. The same information as the text. A better style of presenting it.

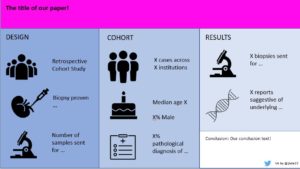

An example of a visual abstract I’ve done for an ongoing manuscript (hence the removal of certain pieces of text. You understand).

You might wonder why I talked about creativity at the beginning of my blog post. One reason — I like to start my post with something relatable (although I’m sure many of our constant readers are much more artistically talented than I am), but another reason was to convey that I don’t think you have to be creatively minded to design and produce an engaging visual abstract. Don’t get me wrong — it doesn’t hurt! I’m sure the ones I have created have terrible colour choices that clash and a layout that definitely could be improved on with some creative flair. But despite my total lack of creativity, I can still produce an abstract which is probably kinda ok. Because, like reading and playing music, they follow a structure (which again, I’m sure others can and have improved on, but my type A personality brain just doesn’t stretch in that fashion) to convey their information, which can be replicated. And while there is a learning curve as to what is/isn’t important and how to convey information in a minimalist manner, once you get the basic components of it down, it’s definitely something many people can pick up and use to produce amazing work. You can even make them in PowerPoint, that staple of presentations everywhere.

I’m fortunate once again that during my NSMC internship, I was mentored in the use of visual abstracts, and completed a project in which we produced them for various publications and honed our skills. I’ve even started to incorporate them into my manuscript submissions to journals as I feel that such things only serve to strengthen a paper (please see one slightly redacted version here — it’s a work in progress). I certainly find them a lot easier to read and engage with on Twitter or other social media platforms. And perhaps you do, too? (It’s slightly ironic, isn’t it, that I’ve written a wall of text in order to champion a simple minimalist visual format? Ah, well).

“You can see everything. You can unsee nothing.”

September 5th, 2019

Building Your Squad — Residency and Beyond

Ellen Poulose-Redger, MD

At nearly every stage in our education and training, we find “our people.” Maybe it’s your table-mate in kindergarten, or the kid with the really cool light up sneakers in preschool who becomes your best friend. Maybe it’s your next-door neighbor who you play with after school, or a coworker from your first job in high school. These people become part of our squad — even if their membership is only transient in this long journey of life. What I’d like to talk (write) about though, is finding your squad in residency.

Match Day, MS4 year:

You nervously check your email or open an envelope to reveal your fate for the next 3-7 years. After all the emotions of where you matched happen in rapid cycle, you think, maybe for a minute — who else is going to be there with me? What happens to my best friends from med school — the ones I spent evenings and nights and weekends with in the library, and the ones who have been with me through the rough rotations and the brachial plexus and the formaldehyde and everything else? How on earth will we move away from each other and be busy interns and stay in touch? [Note to all MS4s — it’s called a group chat, and sometimes you put it on “no alerts” when you’re busy, and sometimes you realize you have 86 missed texts from these people, who will always be part of your squad.]

Orientation to Intern Year:

Everyone shows up, early, on day one and everyone is full of first day jitters. Maybe you’ve moved to a new city or even a new country, maybe you’re still at the same place you went to medical school. Regardless, you’re a newly minted doctor in a room filled with strangers, people you’re about to be in the trenches with for several years. Everyone’s sizing each other up: who’s going to be the social chair? Who’s the gunner? Who’s the one who will have the bag with acetaminophen and ibuprofen when you get a migraine at work? Who knows how to use this EMR system already? If you’re anything like me, you’re trying to settle into a new apartment and figure out how to drive around a new city and do basic things like get groceries, while at the same time trying to make friends and a million other things. You sit through hours of orientation (retirement accounts? I haven’t even gotten a paycheck yet! ACLS certification? Controlled substance prescribing training? I’m barely ready to give a colleague that ibuprofen I carry around, let alone give a stranger anything stronger!) You might go on a retreat with your intern class. It may or may not be a scavenger hunt with insanely hard clues. But, by the end of these few days — you’ve found some people. The ones you will be able to call a year later and go on a spur-of-the-moment “we have to go get a coffee or something stronger together before I go insane” date with. [Note to all interns — these residency BFFs don’t have to be in your program, in your year, or necessarily even doctors at all, but you’ll need someone.]

Sometime in the Middle of Your Training:

Depending on what specialty you’ve entered, this may be your 2nd-5th year of residency. You’re an old pro at things that used to scare you (ACLS and codes, anyone?), have navigated several rounds of medical students and new interns through the EMR, and calmly know how to push metoprolol to control afib with RVR. You’ve learned how to have the difficult conversations on the phone at 2am with patients’ families, learned and forgotten more than you ever thought possible, and probably left the hospital at least once with the bodily fluid of a patient on you. And you’ve done all of these things with a group of colleagues — friends, actually — who you literally can’t remember not knowing. [Note to mid-term residents — this is a good thing, not a sign of early onset dementia.]

Panicked Thoughts in the Last Months of Residency:

Similar to how you felt many moons ago as a MS4, you’re now going to a fellowship or a “real” job as an attending somewhere, and again, you’re (I’m) nervous about how this is going to go. Everyone I’ve been working with for years is moving on to something new, and many of us are also moving to somewhere new. Again — how are we going to stay in touch? How will we stay so close when we don’t see each other for months on end? And, of course, what about the people at the next place? We’re embarking on the next step in our journey, but, again, when we disperse across the country or across the globe, how will we stay connected? [Note to new attendings — Again, it’s technology and social media: texts and direct messages and conversations entirely in memes. And hopefully using vacation days to go see each other or meet up in a cool place.]

In each of these steps in our professional lives, just like in preschool and elementary school and every step before we made it to “being doctors,” we find our people. The ones who it isn’t weird to text and ask for recommendations on compression socks. Or the ones who you’ll complain to and get advice from when your career and personal plans diverge. These people will be your squad, which will grow and shrink over the years and have people like your high school BFFs and your med school BFFs and your college BFFs and your residency BFFs and so many more people in it. Because you’ll need a person you can ask for compression sock recommendations, but also someone who can recommend a good book for pleasure reading and also someone who can send you a great meme with uncanny timing when you’re having a rough day. The days (and nights) might be really long in training, but the years are short — and they’re all so much easier to get through with a good squad at your side.

August 28th, 2019

Status: Post-Residency Syndrome

Ashley McMullen, MD

Today, I’m thinking about the end of residency. But first, let me tell you about the beginning of residency. My first day of clinic, my very first week of residency, I had a grand total of one patient scheduled. A seasoned outgoing resident had given me sign-out on this person, along with some big, knowledgeable shoes to fill. I did my most thorough pre-rounding the evening before. I prepped my note and reviewed the problem list I intended to cover during our visit. Our encounter began with some pleasantries, followed by my well-rehearsed, “What brings you in today?” To which my patient replied, “I really just need these forms filled out by a doctor.”

“Easy enough, I got this!” I thought to myself. Then I noticed the systolic blood pressure that was charted in the 60s. Suddenly I was staring more closely at the ashen skin, sunken eyes, and listless movements in front of me. However, when asked about this, my patient smiled and shrugged me off like I was hallucinating, then gently pushed the forms towards me. We agreed to start with a brief exam: pale conjunctiva, fast, regular heart beat, exquisitely tender abdomen, with overlying skin that was inflamed and indurated. I proceeded to check my own pulse which was racing, and then left to find an attending. Less than 1 hour later, my patient was admitted to the ICU with septic shock from a large abdominal wall abscess.

“Easy enough, I got this!” I thought to myself. Then I noticed the systolic blood pressure that was charted in the 60s. Suddenly I was staring more closely at the ashen skin, sunken eyes, and listless movements in front of me. However, when asked about this, my patient smiled and shrugged me off like I was hallucinating, then gently pushed the forms towards me. We agreed to start with a brief exam: pale conjunctiva, fast, regular heart beat, exquisitely tender abdomen, with overlying skin that was inflamed and indurated. I proceeded to check my own pulse which was racing, and then left to find an attending. Less than 1 hour later, my patient was admitted to the ICU with septic shock from a large abdominal wall abscess.

I spent a lot of time ruminating on what I could have done differently. Why didn’t I call to check on this individual before the appointment? Why didn’t I notice the blood pressure sooner or get an attending faster? What if the resident who signed out to me finds out their former patient ended up in the ICU after one visit with me? Thankfully, that patient ended up being okay, but it was the first of many experiences that would leave a lasting impact.

I spent a lot of time ruminating on what I could have done differently. Why didn’t I call to check on this individual before the appointment? Why didn’t I notice the blood pressure sooner or get an attending faster? What if the resident who signed out to me finds out their former patient ended up in the ICU after one visit with me? Thankfully, that patient ended up being okay, but it was the first of many experiences that would leave a lasting impact.

Residency is an interesting phenomenon. It’s like an invisible threshold, where on one side of July 1 you are light and buoyant. On the other, you are weighed down with the responsibility of people’s lives ostensibly placed on your shoulders. Few professions can match the physical and emotional peaks and valleys that define medical training. Friends and family that aren’t in medicine can find it hard to relate the day-to-day life of a resident. Many times, I would come home to random questions about dramatic traumas or steamy call-room encounters (thanks, Grey’s Anatomy!). Therefore, many times, I would have to explain the role of an internist — that most nights, I’d be lucky just to see the inside of a call room. If I did lay down, it was at the risk of being jolted awake for anything from a cardiac arrest to an FYI page about rabbit allergies.

Currently around the country, thousands of newly matched interns are eagerly crossing that proverbial threshold. On the other side, there awaits experiences that will test the boundaries of their comfort zones and leave them equal parts exhausted and fulfilled. They join other new doctors from various walks of life and form the unyielding bonds of friendship fortified by the shared experience of residency. To borrow the famed quote from Charles Dickens, it is the best of times and the worst of times; and those of us who have already crossed the boundary must continually weigh the virtues of rigorous medical training against the long-lasting impact on physician well-being.

As for myself, I have now started my first “real” job since 2011. It’s been an exciting process, but one in which I’ve also had to grapple with my own post-residency syndrome. I look forward to taking some time off to spend with loved ones and reclaim some parts of myself that didn’t quite make the full journey across the threshold 4 years ago.

August 20th, 2019

Bias in the Residency Ranking Process

Scott Hippe, MD

“Can we please try to be objective about this!” I said these words to myself over and over during this year’s interview season as we formulated our residency rank list. At my institution, the residents and faculty have equal sway in forming the rank list. The chief resident facilitates the resident half of the process. As the hours wore on during our last meeting, the discussion gradually deviated from assessing the applicants’ clinical potential. The focus shifted to peripheral elements of character: “[Applicant] is just really cool and I want them to be my friend,” and similar arguments. I was concerned.

One’s ability to get along with other residents is important. However, it isn’t the only factor to consider when ranking residency applicants. You want a clinically solid incoming class who know their stuff and can keep up with the rigors of residency. Trying to move away from haphazard character judgments, I focused on applicants’ board scores and clerkship grades. Consider a situation where applicants “A” and “B” were equally liked by resident interviewers and were similarly involved in extracurriculars. The fair thing to do would be to use their “stats” to sort out who deserved to be ranked higher. Right? And then I started thinking about those criteria.

I realize that the Insights blog is read by individuals of many different backgrounds and at varying stages of medical training. Depending on who you are, the ensuing comments might be controversial or maybe they are old news. The first, potentially obvious observation: Objective measures aren’t perfect at predicting real-life clinical ability.

“Objective” measures aren’t the be-all, end-all to ranking

- In my experience, USMLE and COMLEX scores (especially Step 1) correlate only loosely with clinical ability. Step 1 isn’t written to be a primary discriminating factor in the residency selection process. Beyond pass/fail, we should stop caring as much about the three-digit score. Seriously, how many practicing physicians need to remember the Krebs cycle? I am not the first one to suggest Step 1 be de-emphasized (Acad Med 2016; 91:12).

- Although of questionable clinical significance, board scores certainly do correlate with demographic characteristics. Namely, higher board scores are associated with having a non-minority background and speaking English as a first language. Incorrect use of board scores in the ranking process solidifies bias against nontraditional and diverse applicants.

- I argue that clerkship grades are not much better. Often they are heavily weighted by standardized testing and thus subject to similar biases as is the USMLE. Clerkship standards also vary from institution to institution. Clerkship performance has some validity internal to the specific medical school, but I would argue that it has less external validity when comparing across schools.

Toward eliminating bias

I cannot say whether there is one completely perfect way to conduct applicant ranking. The Match process provides a decent place to start. I especially appreciate the standardization it brings to the process. But the Match doesn’t eliminate all sources of bias, especially when it comes to test scores and clerkship grades. Despite many efforts to increase diversity in medical education, the proportions of under-represented minorities in medical schools haven’t changed much since 1980.

Consider the imperfections inherent in the metrics we use to evaluate medical students. This should beget humility in the resident selection process. Humility that discovers and celebrates applicants’ life experiences. Humility that de-emphasizes the “objective” measures we use to evaluate our applicants. Humility that breeds a culture of curiosity rather than exclusivity.

The Match this year happened months ago, but soon enough, fall will return and with it, another interview season. If you are involved in a residency, I hope these thoughts challenge next year’s interview process. Lower your USMLE thresholds for interviews. See past the test scores. Look for character. Above all, I propose emphasizing a central evaluation criterion: An applicant’s potential to serve their community and the common good with their medical training.

August 9th, 2019

Duty Hours: Can We Lay This Debate To Rest?

Cassandra Fritz, MD

Cassandra Fritz, MD, is a Chief Resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University Medical School in St. Louis, MO

Duty hours have been the focus of a lot of research recently. If you are just joining this discussion, the iCOMPARE trial randomized 63 internal medicine residency programs to either flexible (interns could work more than 16 hours) or standard (interns had to work within the 16-hour limit) work hours. The results so far have shown no significant difference in the time interns spend on patient care (NEJM JW Gen Med May 1 2018 and N Engl J Med 2018; 378:1494) or hours of sleep (N Engl J Med 2019; 380:905). Most importantly, patient outcomes and 30-day mortality are not adversely affected by flexible duty hours (NEJM JW Gen Med Apr 1 2019 and N Engl J Med 380:915).

With no significant differences in the studied outcomes, we can likely lay the standard vs. flexible duty hour debate to rest. Flexible hours allow programs and program directors to make decisions based on the needs of their patients, hospitals, and trainees. However, duty hours should continue to remain in the spotlight, but for a different reason. I will argue that our next question should be whether current duty hour restrictions are preparing trainees for the world in which they will practice.

ARE DUTY HOURS LIKE THE REAL WORLD?

Like many academic institutions, we are constantly discussing innovative ways to improve the balance between resident wellness, patient continuity, and duty hour compliance. I think these discussions are important, but I do wonder if we are preparing residents for a world that doesn’t currently exist?

Like many academic institutions, we are constantly discussing innovative ways to improve the balance between resident wellness, patient continuity, and duty hour compliance. I think these discussions are important, but I do wonder if we are preparing residents for a world that doesn’t currently exist?

Training programs have built residency systems where residents can call in because they are exhausted or can cite “duty hours” when the maximum number of hours is reached. Personally, I think these are good things when used appropriately. Yet the ability to wave the white flag disappears quickly after training. We foster an illusion that, once you are in independent practice, you no longer suffer from exhaustion or an ever-increasing workload. Although people can choose what type of practice model they join after training, many of us will be in clinic the day before and after covering the ICU, delivering a baby, or completing procedures/surgeries during the night. Attendings don’t have an option to shout “duty hours” when they’re exhausted.

With this in mind, I am thankful that I trained in a rigorous system with flexibility. A program that pushed me to my limits but provided a safety net. I learned valuable lessons about understanding my limits, when to ask for help, and when waving the white flag is not only what is best for my health but also for my patients.

SHOULD DUTY HOURS BE THE “REAL WORLD?”

As we rise in the ranks, our task load continues to increase, whereas the ability to take time off during a call cycle if necessary, seemingly disappears. I understand the need for random time off might be less common in independent practice, but the risk for exhaustion is still there. Therefore, I think our conversation about work hours needs to continue with the following considerations:

As we rise in the ranks, our task load continues to increase, whereas the ability to take time off during a call cycle if necessary, seemingly disappears. I understand the need for random time off might be less common in independent practice, but the risk for exhaustion is still there. Therefore, I think our conversation about work hours needs to continue with the following considerations:

- Should we develop policies that afford attendings some of the same benefits we provide residents in relation to exhaustion?

- Should we consider how task load contributes to exhaustion? Does this, in turn, affect physician performance? If so, are there other skills that we should be cultivating during residency?

- Should our systems provide an environment that works toward mitigating task load to improve physician satisfaction?

- Finally, will all of the above lead to happier more efficient doctors? Will this move the needle on patient satisfaction?

I think the discussion surrounding work hour limitations and restrictions needs to continue but should include the physician workforce as a whole. We might not need sweeping regulations from a national agency, but we should continue to discuss optimal task load in relation to exhaustion, physician satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and overall efficiency for providing care.

NEXT STEPS?

My argument is neither to make training “harder” nor to make attending work “easier.” I just think we should contemplate whether our training environment is reflecting the realities of the task load and work hours that are required to be successful in independent practice. My hope is that we can all work together to continue to have discussions about what’s best for not only our patients and residents but for physicians at ALL levels.

My argument is neither to make training “harder” nor to make attending work “easier.” I just think we should contemplate whether our training environment is reflecting the realities of the task load and work hours that are required to be successful in independent practice. My hope is that we can all work together to continue to have discussions about what’s best for not only our patients and residents but for physicians at ALL levels.

March 14th, 2019

Musings on Match Day, the Conception Day of our Residencies

Ellen Poulose-Redger, MD

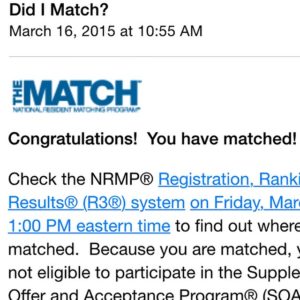

Match Day. The one day that medical students across the United States all simultaneously look forward to and also fear. It’s really a whole week of roller-coaster emotions: on Monday we find out if we matched somewhere, and on Friday we find out where. (And, in between, if we unfortunately didn’t match, we scramble to find a position that is hopefully what we wanted to do but that at least gives us a job for the next 1-7 years.)

I’ve been through several Match Days for residency now, one as a spouse of a MS4 and one as an MS4 myself. (And, I guess, two others as the child of MS4s, but I didn’t know enough then to have any idea what was going on.) These days (weeks) are stressful and exciting at the same time. Stressful waiting — to find out where we are going, what the algorithm determined is the best fit for us based on our preferences and the preferences of the programs at which we interviewed. Stressful wondering — to find out if we’re going to have to move somewhere new or if we’re going to know anyone else who’s going there, or if we’re going to find new friends at a new place. Stressful excitement — to think of a fresh start and another step in our training in medicine. Scary to contemplate it all. And very confusing to explain the process to anyone who isn’t in medicine. Yes, a computer algorithm analyzes preference lists from applicants and programs and then figures out a very important piece of our careers and commits us to a training program.

I’ve been through several Match Days for residency now, one as a spouse of a MS4 and one as an MS4 myself. (And, I guess, two others as the child of MS4s, but I didn’t know enough then to have any idea what was going on.) These days (weeks) are stressful and exciting at the same time. Stressful waiting — to find out where we are going, what the algorithm determined is the best fit for us based on our preferences and the preferences of the programs at which we interviewed. Stressful wondering — to find out if we’re going to have to move somewhere new or if we’re going to know anyone else who’s going there, or if we’re going to find new friends at a new place. Stressful excitement — to think of a fresh start and another step in our training in medicine. Scary to contemplate it all. And very confusing to explain the process to anyone who isn’t in medicine. Yes, a computer algorithm analyzes preference lists from applicants and programs and then figures out a very important piece of our careers and commits us to a training program.

My Match Day as a student was a complete collection of all emotions. I was excited to see where I was going to train for the next 3 years, really hoping it would be at the same place my husband was going, and scared to find out. Scared because, if we didn’t end up at the same place, the 1 year of training in separate cities that we’d already done could end up being 3 or 4 years of living apart. And very nervous that, if all went well, we’d be moving halfway across the country to city where we didn’t know anyone. I remember very nervously walking up to the stage with my husband to get my envelope, opening it with him, and then turning to the microphone to announce where I [we] was going. (My husband, clearly, was very excited that we were going to the same place for the following 4 years.) I remember cheering on my classmates and friends as they found out where they were headed to for the next stage of their training. Some were ecstatic with their matches, and a few were mildly disappointed, but everyone was proud that they had made it to the next step.

years, really hoping it would be at the same place my husband was going, and scared to find out. Scared because, if we didn’t end up at the same place, the 1 year of training in separate cities that we’d already done could end up being 3 or 4 years of living apart. And very nervous that, if all went well, we’d be moving halfway across the country to city where we didn’t know anyone. I remember very nervously walking up to the stage with my husband to get my envelope, opening it with him, and then turning to the microphone to announce where I [we] was going. (My husband, clearly, was very excited that we were going to the same place for the following 4 years.) I remember cheering on my classmates and friends as they found out where they were headed to for the next stage of their training. Some were ecstatic with their matches, and a few were mildly disappointed, but everyone was proud that they had made it to the next step.

As a resident, I also look forward to Match Day. It’s exciting to find out who is coming to join our program, because those matches are a reflection on our program and its current residents, faculty, and leadership. It’s also a reminder that I’m almost done with another year of training and am that much closer to a fellowship or a job. There’s a palpable energy in our program during Match Week as we wait to find out if we filled all of our positions (phew) and then anticipate who will be joining us, and then finally find out who they are. A perk of being a future Chief Resident last year was that Match Day was also the day we found out who the social butterflies of the incoming class would be, as the social media friend/follow requests came flying in.

Match Week marks the beginning of the end of medical school and the start of residency. It’s the time when the promise of graduation becomes very real (which is awesome), and the idea of having a job shortly becomes more concrete. It’s when we start getting paperwork to fill out for hospital privileges and licenses and NPI numbers. It’s when we realize that the last few months of freedom until we retire are coming up and when we look for cheap flights to somewhere to celebrate our accomplishments. And it’s the start of new Facebook groups and WhatsApp groups so that we can stay connected to our medical school friends and make new residency friends.

There’s a temptation to speed up the time between finding out where we are going for residency and actually starting residency. A thought of getting ahead by reading something or learning something or practicing something to help us hit the ground running as interns. Don’t do it. Relax and breathe in those last few weeks of freedom before residency starts. Take the 3 months between Match Week and Intern Orientation to learn more about yourself and take care of yourself and your loved ones. Deepen the friendships you have with your medical school classmates, and be open to new friendships with residency colleagues. After all, once the algorithm has decided where we are going, it’s up to us to make the most of it.

March 8th, 2019

The Oncology Service

Ashley McMullen, MD

I won’t forget Mr. H’s face that morning, my very first morning on the medical oncology service. I skirted into his room behind my attending as she was called in to see him on the fly. With a slight smile, he sat quietly in the corner of the exam room, a tall black male of average build, alone. His open collar shirt and slacks were both wrinkled, his eyes were sullen, his close cropped hair was thinning diffusely throughout the top of his head. Outside this place, perhaps I would’ve pegged him for a car salesman, just working hard to get through the daily grind. Yet inside these clinic walls, I traced the large T-shaped scar extending from his collarbone down to the midpoint of his sternum. I took note of his soft, raspy voice. I observed how his ashen skin was in agreement with his dangerously low blood pressure. But that’s all I knew of Mr. H right then.

My eyes blinked and my attending was back out of the room. She needed to check on the results of Mr. H’s most recent labs and imaging studies. As she scrolled through his chart at a mind-numbing pace, she summarized the medical history… 42 y/o African American male, presented to the ED 4 weeks ago, found to have a mediastinal mass, diagnosed upon surgical removal to be anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. My First Aid lied to me! According to the text I had painstakingly committed to memory, this type of cancer was supposed to be extremely rare, popping up occasionally in elderly white females — not this middle-aged black man with four kids at home. When my attending got to the radiologist’s report, her head dropped slowly into her hands. The poisons we had dripped through this man’s veins last week had managed to shave off 15 lbs of his body weight, his appetite, his hair… basically, everything but the tumor, which had grown back to 3x its size since the initial surgery.We’re back in the exam room. Now the attending is sitting down, next to Mr. H, her eyes meeting his eyes directly as she speaks (ironically, a bad sign in a busy specialty clinic). “I’m sorry Mr. H, but the chemo isn’t working. We can try adding radiation to slow the tumor growth, but in all honesty, this is not likely to do much. You should tell your family, and start making arrangements.” Mr. H accepted his fate with inspiring equanimity and quiet resilience. He even thanked my attending for her efforts as he headed towards the infusion center for IV fluids to bolster his decreased blood volume. I can’t help thinking that, that same evening, while I’m at home hovering over medical journals, Mr. H would be surrendering news of his prognosis to the four young children he was trying to protect. What are you supposed to do, when you’ve effectively derailed a man’s life in the course of a 15-minute visit? What’s the next step when you’ve sent a man home to tell his family that, by Christmas morning, he will be lying in a casket?

February 26th, 2019

My Primary Care Manifesto

Scott Hippe, MD

“She is meant for more than just primary care,” mused an attending on my internal medicine rotation in medical school. He was referring to a particularly adept resident with whom we were working. This resident was planning on practicing clinic-based general internal medicine. I wasn’t sure why this attending disclosed his thoughts regarding this resident to me, but the implication was clear: “primary care” — whatever is meant by the term — is an easy career path, meant for the mediocre clinician.

The comment left me scratching my head, because the general internist who said it worked in the outpatient setting almost exclusively. Something about the outpatient care he provided was apparently different than “primary care.”

A year later, I matched in a family medicine residency. I chose the field not because I had low test scores (I didn’t), but because I couldn’t find a single area of medicine that wasn’t interesting to me. I didn’t want to give anything up. I was attracted by the never-ending challenges afforded a generalist who is willing to push the boundaries of his or her knowledge. Asking “how much can I do [before reaching my limits] in the care of my patient?” is more compelling to me than saying “I know nothing about this particular organ system; this patient needs to go see another specialist.”

Medical education fails trainees interested in primary care

I did my medical training in the Northwest U.S., where the attitude towards primary care is generally favorable. My medical school actively encouraged students to consider primary care fields. But it isn’t that way everywhere. Trainees are frequently told explicitly or implicitly that primary care specialties are second-rate. Family medicine is seen as a convenient fall-back option for students who didn’t ace Step 1. General internal medicine and general pediatrics are the fields for residents who don’t match in their perfect fellowship.

A handful of medical schools even lack a department of family medicine. You might recognize just a few of them on the list mentioned in this article.

Rewriting a paradigm

The attending I mentioned in this post envisioned primary care as stuffy noses and pap smears. The way I see primary care is different. For the docs out there who look down on primary care fields and medical trainees who have received inadequate exposure to generalist medicine, I want to share this paradigm with you.

Primary care is the entirety of care that I provide for my patients as their first provider. This is far more than those stuffy noses and paps. My specialty’s broad scope of training incorporates services such as comprehensive obstetrics including cesarean section, reproductive health, addiction medicine, inpatient medicine, emergency medicine, screening colonoscopy, treadmill stress testing, treating hepatitis C, and end-of-life care. My domain encompasses the clinic, hospital, emergency room, delivery room, and nursing home. And I still visit patients in their homes.

To the undifferentiated medical trainee: staying general in medicine begets a land of huge opportunity and variety.

Generalists, and more of them, please

We’ve all heard about how the US has the highest health costs of any country in the world.

It takes a specially trained eye to focus on the big picture, to treat the whole person, and to be effective in varied care settings. There are 36 countries in the world that deliver better and cheaper healthcare than the U.S. What do they have in common? A strong base of generalists. I am grateful for the well-trained specialists who help me at the limits of my abilities. But the U.S. cannot specialize its way out of its poor-performing and exceedingly expensive health system.

Our hyper-specialized, fee-for-service health system deters many physicians from becoming generalists. Every medical trainee doesn’t need to choose a primary care specialty. But we need more than are

choosing primary specialties now. I advocate against the notion that generalist medicine is inferior to specialist medicine (partialist medicine? for some humor). Primary care is more stimulating and requires more clinical acumen than many realize. Until our medical community changes the way it thinks about generalists, I don’t see our health system improving — whatever political or policy “fixes” might be on the way.

February 19th, 2019

Do You Have a Peer Mentor? Do You Need One?

Cassandra Fritz, MD

Cassandra Fritz, MD, is a Chief Resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University Medical School in St. Louis, MO

Cassandra Fritz, MD, is a Chief Resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University Medical School in St. Louis, MO

Mentorship is a common topic in medicine. We, as a profession, spend significant time discussing, attending workshops about, and researching the role of mentorship. Mentorship is key to personal development, career choice, and improved academic productivity.

Yet, it wasn’t until recently that my understanding of mentorship was challenged. I have always viewed mentorship as someone more senior than myself helping me to achieve my goals. I have always been the mentee in such relationships. I was expecting the opportunity to mentor incredible residents during my chief resident year, but I have been truly surprised by the importance of mentor–mentee relationships with my co-chief residents. For the first time, I am recognizing the invaluable role that my peers play as my mentors. So, this made me wonder… is peer mentorship important in academic medicine?

Yet, it wasn’t until recently that my understanding of mentorship was challenged. I have always viewed mentorship as someone more senior than myself helping me to achieve my goals. I have always been the mentee in such relationships. I was expecting the opportunity to mentor incredible residents during my chief resident year, but I have been truly surprised by the importance of mentor–mentee relationships with my co-chief residents. For the first time, I am recognizing the invaluable role that my peers play as my mentors. So, this made me wonder… is peer mentorship important in academic medicine?

Peer Mentorship

Peer mentorship is two people at similar stages in their career mentoring one another in a reciprocal fashion to advance both careers. It is a nonhierarchal relationship with equal commitment and accountability. These definitions perfectly sum up the relationship I have with my co-chiefs. We work together to make advancements in our program, but we have also mentored each other through personal and professional projects, emails, disagreements, fellowship applications, and research. A peer mentor is likely more relatable and can challenge you in ways that a traditional hierarchal mentor may not be able to. A peer will have a better understanding of your day-to-day successes or shortcomings and can provide a bird’s eye view on the best way to push you toward your goals.

The field of business has established the importance of a nonhierarchical mentor. A recent article in Forbes magazine defines peer mentorship as a “safe place to share difficulties or even failures… as a way to strengthen relationships among collogues and help build resiliency.”1 These principles hold equal importance in medicine, especially in academic medicine. So, what should one consider in establishing a peer-mentoring relationship?

1. Trust and understanding

Trust is critical for obvious reasons, but most importantly, this relationship needs to feel safe. Both people need to provide a protected environment to have open and honest dialogue about goals and career plans. You aren’t depending on your peer to give you opportunities or promotions, unlike traditional mentors. Therefore, you may feel safer in sharing your challenges and be more open to pointed feedback. In my short experience, I have found it easier to hear feedback from my peers, since they aren’t responsible for my advancement. Moreover, this relationship can provide a venue to discuss your concerns prior to taking issues to your traditional mentor.

2. Shared goals

A peer mentor does not necessarily need to be from your field. In fact, having a peer mentor outside your own field might provide better perspective. However, peer mentors must understand each other’s goals and visions and be able to understand the specific pressures within different specialties. If your peer mentor doesn’t understand your vision, he or she can’t help you correct course when necessary.

At the beginning of my chief year, our Chair of Medicine asked us to read Monday Morning Leadership by David Cottrell.2 One of the main points of this book was the importance of “keeping the main thing the main thing.” This concept seems simple, but with competing demands and time limitations, this can be hard in practice. Your peer mentor can be vital in helping remind you what your “main thing” is and how to build your body of work around your overall vision. In short, your peer mentor should understand your goals and provide accountability in your pursuits.

At the beginning of my chief year, our Chair of Medicine asked us to read Monday Morning Leadership by David Cottrell.2 One of the main points of this book was the importance of “keeping the main thing the main thing.” This concept seems simple, but with competing demands and time limitations, this can be hard in practice. Your peer mentor can be vital in helping remind you what your “main thing” is and how to build your body of work around your overall vision. In short, your peer mentor should understand your goals and provide accountability in your pursuits.

3. The importance of resiliency

At the end of the day, a peer mentor should be a supportive resource. Someone that knows how to help you change your view point or plans as necessary. When something negative happens, your peer should be someone that can help you view challenges as opportunities. This relationship should be built on encouragement. You need someone to build you up, help you stay focused, and remind you that academic medicine is a marathon, not a sprint.

My understanding of mentorship has been expanded by my peer-mentoring experience this year. I appreciate that traditional mentorship models are important to career success, but I have come to welcome mentorship from my peers. I wonder if having an effective peer mentor is not only helpful, but is necessary to be successful in academic medicine? Based on my experience this year, I think that it is. Should we, as a profession, be discussing, facilitating, and researching the importance of peer mentorship and its role in retention and promotion of aspiring trainees and junior faculty?

References: